Congenital and Acquired Neuromuscular and Genetic Disorders

Original Editor Kimberley Foy, Susan Hamilton, Alannah Henderson, Sean Lewis, James Millar, Christine Mitchell, Clem Nihill

Top EditorsClem Nihill, Sean Lewis, Shaimaa Eldib, Kim Jackson, Christine Mitchell, Kimberley Foy, James Millar, Laura Ritchie, Alannah Henderson, Mande Jooste, 127.0.0.1, Rucha Gadgil, Lucinda hampton, Tarina van der Stockt, Admin, WikiSysop, Evan Thomas, Mila Andreew, Scott Buxton and Evelin Milev

Introduction[edit | edit source]

According to the WHO, congenital anomalies or birth defects affect one in every 33 infants every year worldwide and result in approximately 3.2 million birth defect-related disabilities every year. The prevalence of major congenital anomalies is 23.9 per 1,000 births for 2003-2007. 80% were live births. 2.5% of live births with congenital anomaly died in the first week of life. 2.0% were stillbirths or fetal deaths from 20 weeks gestation. 17.6% of all cases were terminations of pregnancy following prenatal diagnosis (TOPFA) according to data from EUROCAT (European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies)[1]. Giving birth to a child with such disorders can happen to any mother regardless of age, racial or cultural heritage, socioeconomic status, health or lifestyle. What is Congenital and Acquired?

Congenital Disorder[edit | edit source]

A congenital disorder is one which exists at birth and very often before birth. It also can include those conditions which develop within the first month of birth. Congenital disorders vary widely in causation and abnormalities and can be as a result of genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, infection, birth trauma or the environment the fetus was in whilst in the uterus.

Acquired Disorder[edit | edit source]

Acquired disorders, on the other hand, develop after birth and can develop over the course of one’s life.

1 Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Palsy (CP) is a general term for chronic non-progressive neurological conditions that affect a child's ability to move and to maintain posture and balance [2]. Damage to certain areas of the brain (before or after birth) that control movement and coordination. Every child diagnosed with CP will have unique signs and symptoms. Each case is unique. In general, CP children will not able to control certain muscles in their body the way they are intended to be controlled. It is estimated that 1 in 400 babies in the UK have a type of CP.[3] Every case of cerebral palsy is unique to the individual this is due to the type and timing of the injury to the developing brain.

For further explanation of Cerebral palsy, please visit these pages:

- Cerebral Palsy Introduction.

- Classification of Cerebral Palsy.

- Cerebral Palsy Outcome Measures.

- Cerebral Palsy and Sport.

- Category of : Cerebral Palsy has many pages that help in understanding the condition.

2 Congenital Heart Diseases[edit | edit source]

Congenital heart diseases (CHD), are problems with the heart’s structure that are present at birth. They may change the normal flow of blood through the heart. Congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect.

3 Dystrophy[edit | edit source]

Muscular Dystrophy (MD) is a group of inherited conditions that have a steady degenerative progression[4] which causes muscles to become weak over time[5]. The muscle weakness begins in the legs most often[6]. Some forms of this disease can affect the heart and lungs, which can create life-threatening complications[5]. It is caused by a mutation in the genes responsible for muscle structure, which interferes with the child’s ability to function[5]. As the disease progresses, the level of disability becomes worse. Both boys and girls can be affected by muscular dystrophy, however some affect boys predominantly, such as Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (DMD).

There are many types of muscular dystrophy. Each is classified based on their presentation

| Type | Prevalence | Common Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | 1 in 3,500 | • Difficulty walking, running or jumping • Difficulty standing up • Learn to speak later than usual • Unable to climb stairs without support • Can have behavioural or learning disabilities |

| Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy | 1 in 7,500 | • Sleeping with eyes slightly open • Cannot squeeze eyes shut tightly • Cannot purse their lips |

| Myotonic Dystrophy | 1 in 8000 | • Muscle stiffness • Clouding of the lens in the eye • Excessive sleeping or tiredness • Swallowing difficulties • Behavioural and learning disabilities • Slow and irregular heartbeat |

| Becker Muscular Dystrophy | Varies; 1 in 18,000 – 1 in 31, 000 |

• Learn to walk later • Experience muscle cramps when exercising |

| Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy | Estimated to be in a range of 1 in 14,500 – 1 in 123,000 | • Muscle weakness in hips, thighs and arms • Loss of muscle mass in these same areas • Back pain • Heart palpitations / irregular heartbeats |

| Oculopharyngeal Muscular Dystrophy | 1-9 in 100,000 | • Does not usually appear until age 50-60 • Dropped eyelids • Trouble swallowing • Gradual restriction of eye movement • Limb weakness, especially around shoulders and hips |

| Emery-Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy | 1 in 100,000 | • Develop symptoms in childhood and adolescence • Muscle weakness • Trouble on stairs • Tendency to trip • Slow, irregular heartbeat |

For detailed information about Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy please visit pages:

4-Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease[edit | edit source]

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is known as a hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN) and is the most common inherited neuromuscular disease with a prevalence of approximately 1 in every 2,500 [12]. CMT involves the degeneration of nerve fibres in the body that results in muscle weakness and wasting along with a decrease in sensation [13][14]. CMT is a slowly progressive disorder and it encompasses a large group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders.

For further explanation please visit this page:

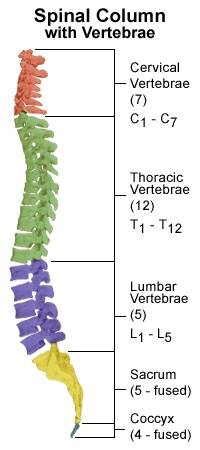

5-Spina Bifida[edit | edit source]

Spina Bifida occurs when there is a problem in the formation of the spine and spinal cord in the developing embryo. It is also known as “split spine” as this developmental fault creates a gap where the spinal column fails to close and protect the spinal cord and associated nerves. This can happen at any level of the spine but most commonly occurs in the lower back or lumbar region [15] The degree of spinal closure and the structures involved can vary in spina bifida and it can therefore be divided into 3 different types [16]:

- Spina Bifida Occulta:

- Spina Bifida Occulta or Spina Bifida Aperta is the least severe form of spina bifida, where only the bony parts of the spine are affected. A small gap remains in the spine which is covered with skin. This can be identified after birth by a small area covered by a tuft of hair or an area of darker skin along the midline of the back. This form of spina bifida can go undetected as it is not associated with significant problems. It is also thought to be present in many healthy adults.

- Meningocoele:

- Meningocoele is the rarest form of spina bifida where the bones of the spine are affected along with the coverings of the spinal cord: the meninges. These can protrude through the gap in the spine to form a cyst, while the spinal cord and nerves remain in place within the spinal canal.

- Myelomeningocoele:

- Myelomeningocoele also know as Meningomyelocele or Spina Bifida Cystica is the most severe form of spina bifida, affecting 1 in 1000 births in the UK. Again, there is absence of closure of the vertebrae, however, this causes leaking of the meninges as well as the spinal cord outside the gap in the spinal column. As a result, a portion of the spinal cord, along with the spinal nerves, protrudes through the gap forming a cyst or sac that lies outside the body.

- Myelomeningocoele also know as Meningomyelocele or Spina Bifida Cystica is the most severe form of spina bifida, affecting 1 in 1000 births in the UK. Again, there is absence of closure of the vertebrae, however, this causes leaking of the meninges as well as the spinal cord outside the gap in the spinal column. As a result, a portion of the spinal cord, along with the spinal nerves, protrudes through the gap forming a cyst or sac that lies outside the body.

For further detailed information, please visit Spina Bifida page.

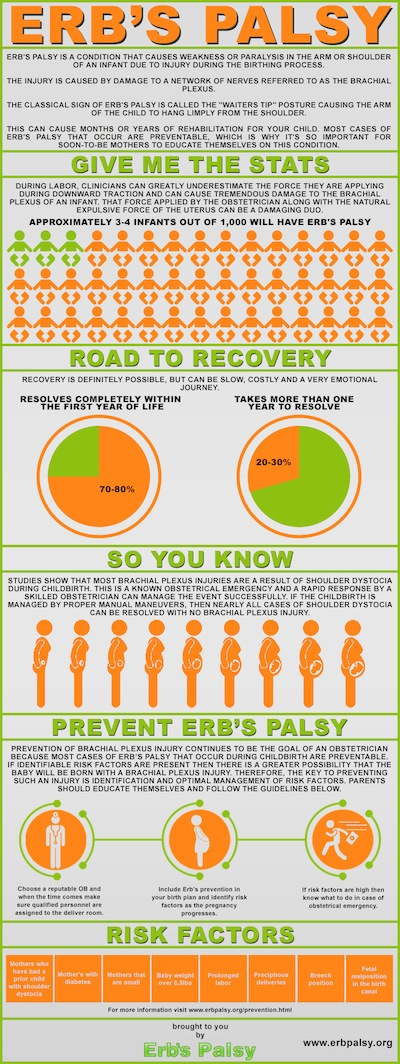

6-Erbs Palsy[edit | edit source]

Brachial Plexus Birth Palsy (BPBP) is also commonly known as Obstetric Brachial Plexus Injury (OBBI) and includes Erb’s Palsy, Klumpke’s Palsy and Erb-Klumpke Palsy.

BPBP occurs through damage to the brachial plexus, a grouping of nerves in the shoulder, during birth. Common causes are believed to be shoulder dystocia, excessive or misdirected traction and hyperextension of the arms during birth[17][18]. A recent study shows that it is impossible to predict BPBP[19].

Nerves coming from the brachial plexus supply the muscles, skin and other tissue of the arm and shoulder. Injuries to the brachial plexus disrupt communication from the arm to the brain[17]. This results in a loss or in altered sensation and loss of muscle function. It is common to see the arm of patients with BPBP to hold their arm in close to their body with it turned inwards. This is sometimes described as the 'Policemans tip'[18].

Birth Brachial Plexus Palsy occurs in between 1.6-2.9 per 1000 live births in developed countries ([20]).

The earlier the signs of recovery the better the prognosis. The return of the function of the biceps muscle in the arm is a key indicator. 95% of infants born with BPBP recover complete function of their arm within 6-12 months while carrying out physiotherapy [18]. However, it is important to understand that each injury is different and that there is a possibility of a lasting disability with BPBP.

For more information please visit Erb's Palsy page.

Microcephaly[edit | edit source]

Microcephaly is a disorder which is present from birth or could develop within the first 2 years of life. It consists of an infant’s skull and brain not growing adequately[21] and being greatly smaller than the average size of other baby’s heads of the same age and gender[22]. Babies head circumference measurement indicates whether or not a baby’s brain is growing as it should be[23].

Causes[edit | edit source]

The condition may be caused by genetic (hereditary) abnormalities or from foetal exposure to drugs, alcohol, maternal diabetes, certain viruses, or toxins during pregnancy, which can lead to damage to the developing brain[22],[22]. Acquired microcephaly could occur after birth if the baby’s infection is present or the brain becomes starved of oxygen[23]. Some children may have normal intellect and the head that will grow bigger, however they will still grow below the normal head circumference[23].

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Symptoms vary with each child depending on the severity of the syndrome, children with microcephaly may have[24],[22],[21]:

- Mental retardation

- Delayed motor functions and speech

- Facial alterations,

- Dwarfism or short stature

- Hyperactivity (abnormally active)

- Seizures

- Difficulties with balance and coordination

- High-pitched cry

- Feeding difficulties

Management[edit | edit source]

Microcephaly is a lifetime condition and some symptoms might become more obvious as the child ages and grows. Physiotherapy management focuses on early childhood intervention programs that may help a child optimise their functional ability via promoting normal development, specific exercises, and provides support to the child as well as their families. This carries on through the child’s adulthood to aid the improvement of quality of life, confidence and to integrate normally at home and in the community[22]. The child’s self-esteem should be strengthened via positive reinforcement to promote as much independence as possible[25]. Furthermore, medications can often be used to manage hyperactivity, control seizures and neuromuscular symptoms. The use of genetic counselling may be appropriate for families understand future risk for microcephaly in later pregnancies[26].

7-Hydrocephalus[edit | edit source]

Hydrocephalus is an abnormal build-up of fluid within and around the brain, which can due to excess fluid production, obstruction to its flow, and inadequate absorption[27] If left untreated, the excess fluid can cause increase the pressure put on the skull and brain, which can be damaging[28]. There are two different types of hydrocephalus, which can affect children, these are congenital and acquired.

For more information please visit Hydrocephalus page.

General Activity Guidelines[edit | edit source]

It is still important to follow certain exercise guidelines, whether a child has a medical condition and/or disability. Children should take part in a variety of activities at moderate to vigorous intensity for at least 60 minutes per day, including weight-bearing activity at least twice weekly. This will provide high physical stresses, which will increase muscle strength, bone health, and flexibility. It is also possible to break down this 60 minute into short, 10-minute sessions and still achieve the same gains[29].

Moderate-intensity physical activity heightens heart and breathing rates to a level the child feels warmer, the pulse can be felt, and may sweat when indoors or on a hot or humid day. Vigorous activity will result in a child being out of breath and/or sweating. Participation in moderate to vigorous activity can range from sport, formal exercise, and other physically demanding exercise (e.g. dancing and swimming) to active play. Activities of daily living, such as walking, climbing stairs and cycling can also give a child some of the 60 minutes of physical activity required[29].

Health practitioners, local authority, and physical activity professionals can make parents and carers aware of the benefits of undertaking 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity a day. Parents should engage with their children whilst taking part in activity, by either encouraging their child and/or getting involved in activities with the child. This can be achieved by acting as a role model and encourage completing local journeys via physically active modes of travel (e.g. walking and cycling)[30]. If these guidelines are met by children, they are at reduced risk of chronic conditions (e.g. obesity) and their general health and wellbeing will be improved[31].

Keeping Active[edit | edit source]

While staying active is extremely beneficial for young people and adults alike, it is important to remember that a disability should not prevent people from being and staying active and talented individuals should be encouraged to perform to the highest level if that is something they wish to do! The following section provides some information on sporting opportunities for individuals with disabilities in the UK.

Disability Sports[edit | edit source]

| Alpine Skiing | Equestrian | Shooting |

| Archery | Football 5-a-side | Wheelchair basketball |

| Badminton | Goalball | Wheelchair curling |

| IPC Biathlon | Ice Sledge Hockey | Wheelchair Dance Sport |

| Boccia | Judo | Wheelchair Fencing |

| Canoe | Powerlifting | Wheelchair rugby |

| Cross-Country skiing | Rowing | Wheelchair tennis |

| Cycling | Sailing | |

More information on the details of each sport can be found on the website of the Paralympic Movement and also in sport-specific fact sheets created by the Scottish Disability Sport , the governing body for sports for people of all ages and abilities with a physical, sensory or learning disability.

There are a number of different organisations who are involved in disability sport throughout the UK.

Associations representing different disabilities and impairments:

- British Amputee & Les Autres Sports Association - https://sites.google.com/a/balasa.org.uk/main/

- British Blind Sport - http://www.britishblindsport.org.uk/

- Cerebral Palsy Sport - http://www.cpsport.org/

- Dwarf Sport UK - http://www.dsauk.org/

Other organisations include:

- Mencap an oragnisation that supports people with learning disabilities to live the life they choose. They have numerous projects, some of which are activated and sport-related. More information can be found at http://www.mencap.org.uk/

- Special Olympics Great Britain provide year-round training and competition for children and adults with learning disabilities encouraging physical fitness, inclusion, development of social skills and the building of friendships - http://www.specialolympicsgb.org.uk/

- Deaf Sports UK looks to encourage Deaf people to participate, enjoy and excel at sport. http://www.ukdeafsport.org.uk/

- Wheel Power - http://www.wheelpower.org.uk/WPower/

Paralympics[edit | edit source]

The British Paralympic Association are responsible for selecting, preparing, funding and managing the athletes representing Great Britain and Northern Ireland in the Paralympics. ParalympicsGB has been extremely successful, coming in top of three of the last four summer games and maintain success on the field, in a range of different sports as one of their main priorities. The association believes that developing and showcasing the Paralympics will help shift perceptions of disability sport and disabled people across the globe.

The association’s current vision for 2012-2017 is:

“Through sport, inspire a better world for disabled people”

Their mission is: “To make the UK the leading nation in Paralympic sport” with regard to performance on the field of play, support for athletes, advocacy and influence, promotion of disability sport and development of opportunities and participation at a grassroots level.

Find out more at: http://www.paralympics.org.uk

The Paralympic Games[edit | edit source]

The first Paralympic Games were held in Rome, Italy in 1960, featuring 400 athletes from 23 countries, competing in 13 sports. The London 2012 Paralympic Games featured more than 4250 athletes from 164 countries taking part in 20 different sports!

The International Paralmypic Committee (IPC)[edit | edit source]

The vision of the IPC, founded as a non-profit organisation in 1989, is “To enable Paralympic athletes to achieve sporting excellence and inspire and excite the world” with its core values outlined as Courage, Determination, Inspiration and Equality. The IPC developed the Paralympic Games to showcase the achievements of athletes with impairments to a global audience in order to change societal perceptions and create lasting legacies.

More information on the IPC can be found at http://www.paralympic.org/

Eligible Impairments[edit | edit source]

The Paralympic movement recognises 10 different impairment types as eligible for participation in the Games, these include:

- Impaired Muscle Power

- Impaired Passive Range of Motion

- Loss of limb or limb deficiency

- Leg-length difference

- Short stature

- Hypertonia

- Ataxia

- Athetosis

- Impairment of the eye, optic nerve or visual cortex

- Intellectual impairment

Get Set[edit | edit source]

Get Set is the official youth engagement programme of the British Paralympic Association and the British Olympic Association. The programme is aimed at inspiring and developing learning opportunities around the Paralympic and Olympic games.

The programme aims to:

- Give all young people the chance to learn about and live the Olympic Values of friendship, excellence and respect and the Paralympic Values of inspiration, determination, courage and equality

- Build excitement about Team GB and ParalympicsGB, using the Olympic and Paralympic Games as a hook for learning and participation

Get Set has resources such as lesson ideas, whole school activities, assemblies and athlete stories, films and images that can be used to engage young people. The programme also will be encouraging young people to complete challenges related to the Paralympic and Olympic games and will be challenging them to ‘travel’ the distance to Rio De Janeiro with their Road To Rio resources!

For more information access the main Get Set website at http://www.getset.co.uk

Information on Paralympians including biographies, blogs, features and interviews can be found at http://www.paralympic.org/athletes

Stories behind the conditions[edit | edit source]

|

A parent of a child with Spina Bifida tells us her story |

|

This is the story of Harrison Smith who was born with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in January 2011 |

Equipment and Aids[edit | edit source]

There is lots of physiotherapy equipment available to support children with Neurological conditions.

- Mobility and standing aids: this equipment is designed to assist with walking or getting around. This may include walkers, crutches and wheelchairs.

- Postural management: mostly seating and sleeping equipment which helps to keep children in good posture and positions to help prevent discomfort, contractures and deformities.

- Equipment for house and home: this equipment is designed to help getting around during daily living activities such as getting out of bed. It can may include grab rails, hoists and transfer aids.

- Play and development: children learn through play and there are lots of adapted toys which can help develop children’s skills and abilities whilst having fun.

- Orthotics and splints: These are braces worn mostly on the arms and legs. They can help prevent deformities, improve walking and control and relieve pressure. They can be functional or accommodative.

There is lots of specialised equipment and methods specifically designed to support CP children, and allowing them to be as independent as possible as well as equipment to help the caregiver to look after these children. Some of this equipment include:

- Special designed clothing for CP children: simplified clothing to make dressing easier.

- Devices to assist with eating and drinking, e.g. eating utensils and bottles

- Bathing items to improve safety and assist with personal hygiene and personal care

- Adapted car seats and vehicles.

Normally an occupational therapist will assess and provide this type of equipment. Physiotherapists and occupational therapists often work together when deciding on what equipment may be best for a child.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Europe. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2010;686:349-64.

- ↑ RITTER, T. (1998) Children with cerebral palsy: a parent's guide. Ed Elaine Geralis; Woodbine House

- ↑ CEREBRAL PALSY. 2013. [online].[viewed 10 November 2014]. Available from: http://cerebralpalsy.org/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 TECKLIN, J.S., 2006. Pediatric physical therapy / [editied by] Jan S. Tecklin. Philadelphia : Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008; 4th ed.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 NHS., 2013. Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 3 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/muscular-dystrophy/Pages/Introduction.aspx

- ↑ MEDLINEPLUS., 2014. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 3 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000705.htm

- ↑ CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION., 2014. Facts About Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 2 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/musculardystrophy/facts.html

- ↑ ORPHANET., 2007. Duchenne and Becker Muscular Dystrophy [online]. [viewed 6 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=EN&Expert=262

- ↑ FSH SOCIETY: FACIOSCAPULOJUMERAL MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY., 2010. About FSHD [online]. [viewed 5 October 2014]. Available from: https://www.fshsociety.org

- ↑ NHS., 2013. Muscular Dystrophy – Types [online]. [viewed 3 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Muscular-dystrophy/Pages/Symptoms.aspx

- ↑ SUOMINEN, T., BACHINSKI, L., AUVINEN, S., HACKMAN, P., BAGGERLY, K., ANGELINI, C., PELTONEN, L., KRAHE, R. and UDD, B., July 2011. Population frquency of myotonic dystrophy: higher than expected frequency of myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2) mutation in Finland.vol. 19, no. 7 pp. 776-82 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21364698

- ↑ REILLY, M., MURPHY, S. and LAURA, M., 2011. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System. vol. 16, pp. 1-14

- ↑ PAREYSON, D. and MARCHESI, C., 2009. Diagnosis, natural history, and management of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Lancet Neural. vol. 8, pp. 654-657.

- ↑ LAFARGE, C., TALSANIA, K., TOWNSHEND, J. and FOX, P. 2014. Living with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: a qualitative analysis. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. October/November, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 226-235.

- ↑ TAPPIT-EMAS, E., 2008. Spina Bifida. In J.S, TECKLIN, 4TH eds. Pediatric Physical Therapy. Phyiladelphia: Wolters Kluwer & Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, pp. 231-280

- ↑ SANDLER., A.D., 2010. Children with Spina Bifida: Key Clinical Issues. Pediatr Clin N Am. Vol. 57, pp. 879-892.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 ZAFEIRIOU, D.I. and PSYCHOGIOU, K., 2008. Obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Pediatr Neurol. Vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 235-242

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 YANG, L.J.S., 2014. Neonatal brachial plexus palsy—Management and prognostic factors. Seminars in Perinatology. Vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 222-234

- ↑ OUZOUNIAN, J.G., 2014. Risk factors for neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Seminars in Perinatology. Vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 219-221

- ↑ PONDAAG, W., MALESSY, M.J.A., VAN DIJK, J.G. and THOMEER, R.T.W.M., 2004. Natural history of obstetric brachial plexus palsy: a systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. Vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 138-144.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 SHEPHERD, R.B., 1995. Physiotherapy in Paediatrics. 3rd ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 YORKSHIRES CHILDREN’S PHYSIOTHERAPY., 2014. [online]. [viewed 13 October 2014] Available from: http://www.yorkshirechildrensphysiotherapy.co.uk/conditions-treated/congenital-and-acquired-neuromuscular-and-genetic-disorders/

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 HEALTHLINE., 2014. [online]. [viewed 23 October 2014] Available from: http://www.healthline.com/symptom/microcephaly

- ↑ MEDICINENET., 2014. [online]. [viewed 23 October 2014] Available from: http://www.medicinenet.com/microcephaly/page2.htm#what_are_the_signs_and_symptoms_of_microcephaly

- ↑ CLEVELAND CLINIC CHILDREN’S., 2011. [online]. [viewed 15 October 2014] Available from: http://my.clevelandclinic.org/childrens-hospital/health-info/diseases-conditions/hic-Microcephaly

- ↑ MEDICINENET., 2014. [online]. [viewed 13 October 2014] Available from: http://www.medicinenet.com/microcephaly/page3.htm

- ↑ SHEPHERD, R.B., 1995. Physiotherapy in Paediatrics. 3rd ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

- ↑ SOCCI, D.J., BJUGSTAD, K.B., JONES, H.C., PATTISAPU, J.V. and ARENDASH, G.W., 1999. Evidence that oxidative stress is associated with the pathophysiology of inherited hydrocephalus in the h-tx rat model. Experimental Neurology. January, vol. 155, no. 1, pp. 109–117.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 NICE, Promoting physical activity for children and young people. 2009. [online]. [viewed 14 November 2014] Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph17/chapter/1-recommendations#definitions

- ↑ NICE, Promoting physical activity for children and young people. 2009. [online]. [viewed 14 November 2014] Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph17/chapter/1-recommendations

- ↑ NICE, Promoting physical activity for children and young people. 2009. [online]. [viewed 14 November 2014] Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph17/chapter/2-public-health-need-and-practice