Acoustic Neuroma

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Kim Jackson, Candace Goh, WikiSysop, Lucinda hampton, Evan Thomas, Naomi O'Reilly and Vidya AcharyaClinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

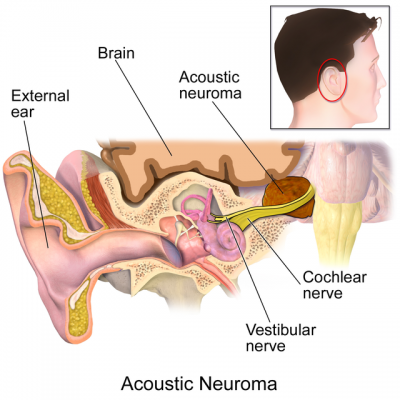

The Acoustic (or Vestibulocochlear) nerve is the 8th cranial nerve. It has a cochlear portion (Cochlear Nerve) which is concerned with hearing, and a vestibular portion (Vestibular Nerve) which is involved with the sense of balance and head position. The fibres of the cochlear nerve originate from neurons of the spiral ganglion and project to the cochlear nuclei. The fibres of the vestibular nerve arise from neurons of Scarpa's ganglion and project to the vestibular neuclei.

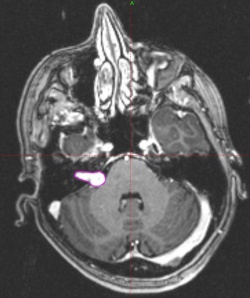

Acoustic Neuroma outlined in pink:

Incidence[edit | edit source]

The incidence of acoustic neuroma is approximately 1.2 per 100,000 population per year[1][2].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Acoustic Neuroma is a benign, slow growing brain tumour, originating from the Schwann cells in the myelin sheath of the vestibular portion of the 8th Cranial Nerve, the Vestibulococholear or Acoustic Nerve.

Generally, the tumour grows slowly, and can stay in the bony ear canal for decades. If it is (still) completely inside its position it is called intrameatal.

If it has grown larger and there is not enough space in the ear canal after pushing and suppressing the nerves and vessels passing through, the acoustic neuroma grows out of the ear canal and into the cerebellopontine angle, in one of the divided spaces left and right of the extended spinal cord, into the brain stem. In these cases the tumour is called a Cerebellopontine Angle Tumour.

Acoustic Neuroma AKA Vestibular Schwannoma[edit | edit source]

Should it be referred to as Acoustic Neuroma or Vestibular Schwannoma?

As the tumour does not grow on the acoustic (or cochlear) portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve, and as it is not a true Neuroma (= Nerve Tumour) but is a Schwannoma (= Nerve Sheath Tumour) there can be no argument that Vestibular Schwannoma is the more accurate name.

This tumour is also sometimes named Cerebellopontine Angle Tumour.

Growth Rate[edit | edit source]

The average growth rate of an acoustic neuroma is approximately 2mm a year though occasionally a tumour can grow more quickly, and frequently stops growing all together. In fact, up to 60% of Acoustic Neuromas do not grow at all following diagnosis

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Early Signs[edit | edit source]

Hearing Loss[edit | edit source]

The most frequent and common first symptom is a decrease in hearing on one side[3]. In most cases the loss of hearing occurs slowly and subtly. Those affected often notice the hearing problem very late or by chance, for example when telephoning or during a routine examination. Above all, high-frequency hearing difficulties are noticed - suddenly one can no longer hear the birdsong or it has changed. Approximately 90% of people with Acoustic Neuroma experience some degree of hearing loss.

Tinnitus[edit | edit source]

The increasing hearing difficulties are often accompanied tinnitus, often referred to as "ringing in the ears", Tinnitus is the sensation of hearing ringing, buzzing, hissing, chirping, whistling, or other sounds. The noise can be intermittent or continuous, and can vary in loudness. Tinnitus may even be the first symptom, without the person affected having or experiencing hearing loss. Like hearing loss, tinnitus is also present mostly in the high-frequency range. in cases of Acoustic Neuroma.

Balance/Vertigo[edit | edit source]

Although acoustic neuromas mostly originate from the upper part of the balance nerve, vertigo and impaired balance rank only in third place as a symptom of an acoustic neuroma. They appear as swaying dizziness, and as vertigo and unstable walking. Often only after being asked directly do acoustic neuroma sufferers admit to experiencing an occasional vague feeling of instability, mostly in the dark and with sudden head and body movements. As the vestibular portion of the nerve is compressed the ability to maintain balance may decrease, but as this usually occurs slowly, brain adapts and compensates for this change. As a result, many people barely notice any change in their balance. Alternatively the patient may have signs of ataxia[3].

Facial paresthesia may also be an early sign[3].

As the tumour grows very slowly, in most cases (with the exception of Neurofibromatosis patients) the symptoms usually start after age 30 years.

Later Signs[edit | edit source]

An acoustic neuroma growing towards the skull base can interfere with the functions of other cranial nerves and vessels, which supply the brain and lead into the brain through the openings in the skull base.

If the 7th cranial nerve (Facial Nerve) is impaired this leads to motor failures in the face, as this nerve is responsible for facial muscles, amongst other things. Facial paralysis AKA facial palsy can ensue and the production of tear fluid (leading to Dry Eye) and secretions from the nose and palate are frequently affected. Eventually, the sense of taste in two thirds of the tongue may also suffer.

If the 5th cranial nerve (Trigeminal Nerve) is impaired this leads to sensation problems, numbness or facial pain, i.e. trigeminal neuralgia. These symptoms occur less frequently because this cranial nerve passes further away from the cerebellopontine angle.

It is similar with the 9th cranial nerve ( Glossopharyngeal Nerve) and 10th cranial nerve (Vagal Nerve). Impairments to these nerves lead to problems swallowing, painful swallowing and taste disorders in the rear third of the tongue, amongst other problems.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Imaging[edit | edit source]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the main method for imaging Acoustic Neuromas[4][5].

- Computer Tomography (CT) is the second examination procedure of choice[6]. It is used:

- when patients cannot be examined with an MRI ( e.g. magnetisable metallic implants, pacemakers and other active (electronic/magnetic) control devices, claustrophobia, etc.)

Audiometry[edit | edit source]

A test of hearing function, which measures how well the patient hears sounds and speech, is usually the first test performed to diagnose acoustic neuroma. The patient listens to sounds and speech while wearing earphones attached to a machine that records responses and measures hearing function. The audiogram may show increased "pure tone average" (PTA), increased "speech reception threshold" (SRT) and decreased "speech discrimination" (SD).

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

As Acoustic Neuromas are benign and generally very slow growing, often the decision at least initially is to monitor growth and take no further action[7]. For patients with very small, asymptomatic tumors, elderly patients, and patients with other serious medical problems, a conservative approach with observation including serial MRI studies may be the only action indicated.

If tumour removal or debulking is indicated[8], the following methods can be used:

- Conventional micro-surgical removal[9]

- Radiotherapy methods to reduce size of tumour and prevent furthergrowth, include: fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery[10], Gamma knife, Cyberknife, proton beam therapy

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The differential diagnosis includes:

Meningeoma, facial schwannoma, lipoma, lymphoma, hamartoma, hemangioma, AV malformation, bleeding, arachnoiditis, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, labyrinthitis, neuritis, cochlear otospongiosis, neurovascular compression syndrome.

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Post surgery, customized vestibular rehabilitation incorporating adaptation, habituation, balance and mobility has been demonstrated to improve balance[11].

If the patient has sustained facial palsy post surgical removal of Acoustic Neuroma, physiotherapy is indicated to improve outcomes in terms of facial range of movement, symmetry and function.

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kshettry VR, Hsieh JK, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. Incidence of vestibular schwannomas in the United States. J Neurooncol. 2015 Sep;124(2):223-8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1827-9. Epub 2015 May 30. PMID: 26024654.

- ↑ Babu, R., Sharma, R., Bagley, J. H., Hatef, J., Friedman, A. H., & Adamson, C. (2013). Vestibular schwannomas in the modern era: epidemiology, treatment trends, and disparities in management, Journal of Neurosurgery JNS, 119(1), 121-130. Retrieved Feb 12, 2022, from https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/119/1/article-p121.xml

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Oncol Lett. 2013 Jan;5(1):57-62. Epub 2012 Oct 31. Clinical features of intracranial vestibular schwannomas. Huang X, Xu J, Xu M, Zhou LF, Zhang R, Lang L, Xu Q, Zhong P, Chen M, Wang Y, Zhang Z.

- ↑ Neuroradiology. 1992;34(2):144-9.fckLRMagnetic resonance imaging of acoustic neuromas: pitfalls and differential diagnosis.fckLRLhuillier FM, Doyon DL, Halimi PM, Sigal RC, Sterkers JM.

- ↑ Zimmermann, J., Jesse, S., Kassubek, J. et al. Differential diagnosis of peripheral facial nerve palsy: a retrospective clinical, MRI and CSF-based study. J Neurol 266, 2488–2494 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09387-w

- ↑ AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986 Jul-Aug;7(4):645-50.fckLRCT in diagnosis of acoustic neuromas.fckLRWu EH, Tang YS, Zhang YT, Bai RJ.

- ↑ J Neurosurg. 2012 Sep;117(3):514-9. doi: 10.3171/2012.5.JNS111858. Epub 2012 Jun 22. Paradoxical trends in the management of vestibular schwannoma in the United States. Lau T, Olivera R, Miller T Jr, Downes K, Danner C, van Loveren HR, Agazzi S.

- ↑ Régis J, Roche PH, Delsanti C, Thomassin JM, Ouaknine M, Gabert K, et al. Modern management of vestibular schwannomas. Prog Neurol Surg 2007;20:129-41.

- ↑ Neurosurg Focus. 2012 Sep;33(3):E13. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.FOCUS12206. Extent of resection and early postoperative outcomes following removal of cystic vestibular schwannomas: surgical experience over a decade and review of the literature. Yashar P, Zada G, Harris B, Giannotta SL.

- ↑ Neurosurgery. 1995 Jan;36(1):215-24; discussion 224-9. Outcome analysis of acoustic neuroma management: a comparison of microsurgery and stereotactic radiosurgery. Pollock BE, Lunsford LD, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Bissonette DJ, Kelsey SF, Jannetta PJ.

- ↑ Vereeck L, Wuyts FL, Truijen S, De Valck C, Van de Heyning PH. The effect of early customized vestibular rehabilitation on balance after acoustic neuroma resection.. Clin Rehabil. 2008 Aug;22(8):698-713