Anorexia Nervosa

Original Editors - Brittney Kerchief from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Brittney Kerchief, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Tony Lowe, Elaine Lonnemann, Wendy Walker, George Prudden, WikiSysop and Vidya Acharya

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder defined by restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight. Patients will have an intense fear of gaining weight and distorted body image with the inability to recognize the seriousness of their significantly low body weight.[1]

The long‐term prognosis is often poor, with severe developmental, medical and psychosocial complications, high rates of relapse and mortality.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa is 0.66-1.9% based on geographical location, with a higher prevalence in developed countries.

- Females are ten times more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa compared to men.

- The lifetime incidence of anorexia nervosa has increased from 0.1 to 5.4 per 100,000 over the last fifty years.

- In females aged 15-19 years, the incidence has increased from 56.4 to 109 per 100,000 person-years.[3]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Studies demonstrate biologic factors play a role in the development of anorexia nervosa in addition to environmental factors. Genetic correlations exist between educational attainment, neuroticism, and schizophrenia. Patients with anorexia nervosa have altered brain function and structure there are deficits in neurotransmitters dopamine (eating behavior and reward) and serotonin (impulse control and neuroticism), differential activation of the corticolimbic system (appetite and fear), and diminished activity among the frontostriatal circuits (habitual behaviors). Patients have co-morbid psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.[1]

The elements that contribute to the development of anorexia nervosa are complex, and involve a range of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Any person, at any stage of their life, is at risk of developing an eating disorder. An eating disorder is a mental illness, not a choice that someone has made.[4]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

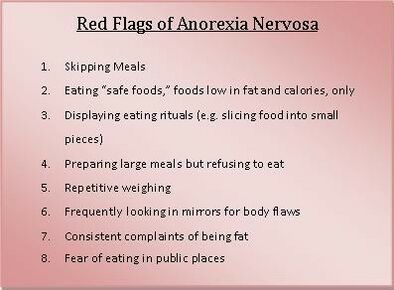

Patients will report symptoms such as amenorrhea, cold intolerance, constipation , extremity edema, fatigue, and irritability. They may describe restrictive behaviors related to food like calorie counting or portion control, and purging methods, for example, self-induced vomiting or use of diuretics or laxatives. Many exercise compulsively for extended periods of time[1]

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) recognises the following criteria for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa

- a restriction of caloric intake

- low body weight relative to age, sex and health

- unjustified fear of weight gain

- body dysmorphia

Along with these, numerous signs may be observed and they include - but are not limited to - the following:

- amenorrhoea (from suppression of the gonadal axis)

- dental caries (from purging)

- orthostatic hypotension or tachycardia

- resting bradycardia

- purpurae[3]

Two sub-types of anorexia nervosa have been recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

- Restricting subtype is characterized by an individual with anorexia nervosa who has not regularly taken part in bingeing or purging behaviors during the current episode.

- Bingeing and purging behaviors include the use of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, and self-induced vomiting to restrict weight gain. Binge-eating-purging subtype is characterized by an individual who has regularly taken part in binge-eating or purging behaviors in the current episode of anorexia nervosa. [5][6]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Death is the most devastating co-morbidity present with this eating disorder and most commonly occurs due to symptoms of starvation or suicide. Medical conditions typically causing death consist of abnormal heart rhythms and imbalances of electrolytes. Mortality rates are as high as 5.9% in anorexia nervosa diagnoses.

- Co-morbid conditions present in individuals with anorexia nervosa may also include "major depressive disorder (50-75% of cases), sexual abuse (20-50% of cases), obsessive compulsive disorder (25% of cases), substance abuse (12-18% of cases), and bipolar disorder (4-13% of cases)". [5]

- Anemia, mitral valve prolapse, osteoporosis, and stress fractures are examples of co-morbidities that may be present with any eating disorders. Many individuals with anorexia nervosa often develop other types of eating disorders as well. Up to 50% of individuals with anorexia nervosa develop characteristics of bulimia nervosa over the span of their lifetime.[5]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

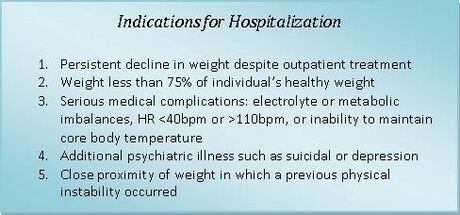

Treatment for anorexia nervosa is centered on nutrition rehabilitation and psychotherapy. Patients who need inpatient treatment have the following characteristics:

- Existing psychiatric disorders requiring hospitalization

- High risk for suicide (intent with highly lethal plan or failed attempt)

- Lack of support system (severe family conflict or homelessness)

- Limited access (lives too far away to participate in a daily treatment program)

- Medically unstable (bradycardia, dehydration, hypoglycemia or poorly controlled diabetes, hypokalemia or other electrolyte imbalances indicative of refeeding syndrome, hypothermia, hypotension,, organ compromise requiring acute treatment)

- Poorly motivated to recover (uncooperative, preoccupied with intrusive thoughts)

- Purging behaviors that are persistent, severe, and occur multiple times a day

- Severe anorexia nervosa (less than 70% of ideal body weight or acute weight loss with food refusal)

- Supervised feeding and/or specialized feeding (nasogastric tube) required

- Unable to stop compulsively exercising (not a sole indication for hospitalization).

Outpatient treatment includes intensive therapy (2 to 3 hours per weekday) and partial hospitalization (6 hours per day). Pediatric patients benefit from family-based psychotherapy to explore underlying dynamics and restructure the home environment.

Refeeding syndrome can occur following prolonged starvation. As the body utilizes glucose to produce molecules of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), it depletes the remaining stores of phosphor.

Also, glucose entry into cells is mediated by insulin and occurs rapidly following long periods without food. Both cause electrolyte abnormalities such as hypophosphatemia and hypokalemia, triggering cardiac and respiratory compromise. Patients should be followed carefully for signs of refeeding syndrome and electrolytes closely monitored.

Pharmacotherapy is not used initially. For acutely ill patients who do not respond to initial treatment, olanzapine is a first-line medication. Other antipsychotics have not demonstrated similar effects on weight gain. For patients who are not acutely ill but have co-morbid psychiatric conditions such as generalized anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder, combination therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and therapy is best. Patients who do not respond to SSRIs may need a second-generation antipsychotic. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are less-preferred due to concerns about cardiotoxicity, especially in malnourished patients. Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with eating disorders due to the increased risk of seizures[1]

Nutritional therapy guidelines include weight gain of .9 - 1.4 kg per week for inpatient treatment and .22 - .45 kg per week for outpatient treatment. Initially daily caloric goals should reach 1000-1600 kcal in divided meals and bathroom use should be restricted for two hours following each meal. Once a healthy weight is maintained stretching can be reintroduced followed by aerobic exercise with supervision and counselling on proper exercise guidelines.[4]

Recovery[edit | edit source]

It is possible to recover from anorexia nervosa, even if a person has been living with the illness for many years. The path to recovery can be long and challenging, however, with the right team and support, recovery is possible. Some people may find that recovery brings new under standing, insights and skills.[4]

Medication[edit | edit source]

Medication can be used to manage various aspects of the complications that come with Anorexia Nervosa. Pharmacotherapy is not used initially.

For acutely ill patients who do not respond to initial treatment, olanzapine is a first-line medication. Other antipsychotics have not demonstrated similar effects on weight gain. For patients who are not acutely ill but have co-morbid psychiatric conditions such as generalized anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder, combination therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and therapy is best. Patients who do not respond to SSRIs may need a second-generation antipsychotic. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are less-preferred due to concerns about cardiotoxicity, especially in malnourished patients. Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with eating disorders due to the increased risk of seizures[1]

- Quetiapine is an atypical antipsychotic. Low-dose quetiapine treatment can help with both psychological and physical improvements, with minimal associated side-effects, and appears to be a promising candidate for the treatment of anorexia nervosa.[7]Olanzaniness, another atypical antipsychotic can also be used to assist with weight gain and obsessive thinking in patients.[8]

- Prozac can help with depressive symptoms and potentially with healthy weight maintenance once weight restoration is achieved. Prozac is part of the SSRI family, or the selective serotonin uptake inhibitors. SSRIs assist with increased serotonin levels, that is connected to mood.[8]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy is an integral part in rehabilitation of patients with anorexia nervosa once stretching and exercise is reintroduced. A health care provider who has extensive knowledge of proper exercise guidelines and how to monitor physical signs of fatigue and vitals is needed to treat these patients. These skills are important to help the patient learn to monitor levels of fatigue and heart rate in order to prevent them from over exercising or exercising to the point of exhaustion. Patients with anorexia nervosa are also more susceptible to orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, and muscle cramping due to malnutrition and low level caloric diets. A health care provider, such as a physical therapist, is the best trained professional to monitor and respond to these medical conditions.

A physical therapist can also be beneficial during the screening process because they are educated in their professional programs on how to recognize the signs and symptoms of this disorder. A therapist may be the first provider to notice signs and symptoms present with this disorder. For example, during a cervical exam the therapist may note edema in the face or salivary glands or overuse injuries like stress fractures from excessively exercising.

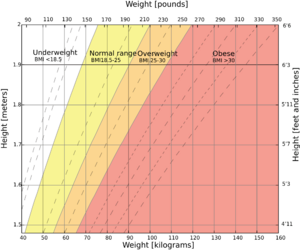

When creating exercise programs for these individuals, physical therapists must take into account bone density levels, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac status, and lab values. The program must be adjusted in order to protect the individual from physical harm or becoming medically unstable. Exercise is not recommended if the patients body mass index is less than 18 kg/m2, and therefore is not introduced until the individual can maintain a healthy weight and is medically stable. The ideal exercise program should include elements of stretching, light upper body weights, breathing exercises, and aerobic exercise. It is very important for the physical therapist to set upper limits on repetitions, sets, or minutes in order to prevent the individual from over exercising. Encouraging the individual to focus on the positive effects of exercise on overall health and not weight is equally important for the physical therapist. [9]

[edit | edit source]

- Below BMI 14: Exercise is not recommended because weight gain at this stage is the overriding priority.

- Between BMI 14 and 15: Following assessment it may be appropriate to recommend exercises in lying and sitting eg gentle Pilates, relaxation techniques and gentle stretches.

- BMI 15 to 17: Commence a gradual progression to moderate weight bearing activities. Pilates, Tai Chi and Yoga type exercises can be introduced. Sessions should still be carefully monitored and supervised and preferably done in a group setting.

- BMI 17 and above, towards a healthy weight: At this point patients are still on a weight-restoration programme and, therefore, any recommendations for exercise must not be allowed to compromise this. Sessions may become increasingly active eg swimming, walking, dancing. Group exercises are preferable to solitary exercising.

- At a healthy weight: Patients need to find a healthy balance between activity levels and nutritional intake. The physiotherapist has a special role in formulating and constantly reassessing an activity/exercise regime. Adjustments must take into account the individual’s physical health, pre- morbid exercise behaviour, occupation and recreational preferences.[1]

Strategies to reduce excessive exercise[edit | edit source]

Although patients might find exercise helps with the weight restoration process, excessive exercise is always counter-productive to its success. Excessive exercise may be a problem for patients at any stage of recovery. Various strategies may be used to help the patient to stop or reduce the inclination to over- exercise. Below are some examples of strategies

- Increasing support, through constant observation for a short period of time to prohibit over-exercising, may not only break the habit, but also appease the guilt. Patients often report that they feel a sense of relief, as they now have an excuse to give up the over-exercising which they had felt compelled to do.

- Promoting a motivational stance is helpful and encouraging patients to adhere to a prescribed exercise programme.

- Distraction techniques, particularly at the time of the urge to exercise, can be helpful for reducing excessive exercising behaviour. eg verbalising thoughts and feelings is appropriate, while for others engaging in a sedentary activity, such as having a painting, can be more helpful. Education and advice play a key role in helping the patient to understand the consequences of over-exercising and in raising awareness about the benefits of change to their health and may help the patient to develop healthier, more appropriate exercise behaviour.

- A CBT approach can be used to guide the patient in finding, new healthier ways of thinking regarding their exercise and activity and make changes to their behaviour.[10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Cancer

- Chronic mesenteric ischemia

- Achalasia

- Malabsorption

- Hyperthyroidism

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Celiac disease[1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

A great place to start is the following link:

https://cpmh.csp.org.uk/content/physiotherapy-eating-disorders

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Moore CA, Bokor BR. Anorexia Nervosa. [Updated 2021 Jun 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459148/ (accessed 9.8.2021)

- ↑ Fisher CA, Skocic S, Rutherford KA, Hetrick SE. Family therapy approaches for anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD004780. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004780.pub4. Available: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004780.pub4/full Accessed 09 August 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radiopedia Anorexia Nervosa Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/anorexia-nervosa (accessed 9.8.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 National eating disorder Association. Anorexia nervosa. Available:https://nedc.com.au/eating-disorders/eating-disorders-explained/types/anorexia-nervosa/ (accessed 10.8.21)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Franco, Kathleen N. Eating Disorders. Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education Website. 2009. Available at: http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/psychiatry-psychology/eating-disorders/. Accessed February 20, 2010.

- ↑ Mitchell, James E. Outpatient Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Guide for Therapists, Dietitians, and Physicians. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press. 2001. p 14-27.

- ↑ Court A, Mulder C, Kerr M, Yuen HP, Boasman M, Goldstone S, Fleming J, Weigall S, Derham H, Huang C, McGorry P, Berger G. Investigating the effectiveness, safety and tolerability of quetiapine in the treatment of anorexia nervosa in young people: a pilot study. J Psychiatr Res. 2010 Nov;44(15):1027-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.011. Epub 2010 May 5. PMID: 20447652.Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20447652/ (accessed 10.8.2021)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Eating disorders hope. Common medications in anorexia nervosa. Available:https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com/blog/common-medication-treatments-anorexia (accessed 10.8.2021)

- ↑ Goodman, Catherine C. and Fuller, Kenda S. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- ↑ cpmh Physiotherapy guidance notes for exercise and physical activity in adult patients with anorexia and bulinia Available : https://cpmh.csp.org.uk/system/files/physiotherapy_guidance_notes_for_exercise_and_physical_activity_in_adult_patients_with_anorexia_and_bulimia_nervosa.pdf (accessed 13.8.2021)