Benign Positional Paroxysmal Vertigo (BPPV)

Original Editors - Steve Blakely

Top Contributors - Chris Milne, Lee Marshall, Lauren Russell, Brían Lillis, Kim Jackson, Kai A. Sigel, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Admin, Anna Thommasen, 127.0.0.1, Ahmed M Diab, Scott Buxton, Candace Goh, Lucinda hampton, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Tony Lowe, Wendy Walker, Melanie Reis and Karen WilsonDefinition/Description[edit | edit source]

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of vertigo, which is a symptom of the condition[1]. Though not fully understood, BPPV is thought to arise due to the displacement of otoconia (small crystals of calcium carbonate) from the maculae[1] of the inner ear into the fluid-filled semicircular canals. These semicircular canals are sensitive to gravity and changes in head position can be a trigger for BPPV[2]. The posterior canal is the most commonly affected site, but the superior and horizontal canals can be affected as well[3]. It should be noted that the superior canal is sometimes also referred to as the anterior canal and the horizontal canal is sometimes referred to as lateral canal.

The peripheral vestibular labyrinth contains sensory receptors in the form of ciliated hairs in the three semicircular canals and in the ear’s otolithic organs. They respond to movement and relay signals via the eighth cranial nerve. Visual perception such as gravity, position, and movements also receive signals from somatosensory receptors in the peripheral vestibules. With the displacement of the otoconia into the semicircular canals, these delicate feedback loops relay conflicting signals that can result in any symptom related to BPPV[4].

BPPV can be classified as cupulolithiasis and canalithiasis. Cupulolithiasis is when the otoconia are adhered to the cupula, whilst canalithiasis is when the otoconia are free floating in the canal. Additionally, the type of nystagmus that a patient may display can be classified as geotropic or apogeotropic. Geotropic describes the nystagmus as a horizontal beat towards the ground. Apogeotropic describes the nystagmus as a horizontal beat towards the ceiling[5].

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a specific type of vertigo that is brought on by a change in position of the head with respect to gravity. This disorder is caused by problems in the inner ear. Its symptoms are repeated episodes of positional vertigo, that is, of a spinning sensation caused by changes in the position of the head.[7]

The vestibular system monitors the motion and position of the head in space by detecting angular and linear acceleration. The 3 semicircular canals in the inner ear detect angular acceleration and are positioned at near right angles to each other. Each canal is filled with endolymph and has a swelling at the base termed the ampulla. The ampulla contains the cupula, a gelatinous mass with the same density as endolymph, which in turn is attached to polarized hair cells. Movement of the cupula by endolymph can cause either a stimulatory or an inhibitory response, depending on the direction of motion and the particular semicircular canal[8]. There is a vestibular apparatus within each ear so under normal circumstances, the signals being sent from each vestibular system to the brain should match, confirming that the head is indeed rotating to the right, for example.

Within the labyrinth of the inner ear lie collections of calcium crystals known as otoconia. In patients with BPPV, the otoconia are dislodged from their usual position within the utricle and they migrate over time into one of the semicircular canals (the posterior canal is most commonly affected due to its anatomical position)[8]. When the head is reoriented relative to gravity, the gravity-dependent movement of the heavier otoconial debris (colloquially ear rocks or crystals) within the affected semicircular canal causes abnormal (pathological) fluid endolymph displacement in the affected ear. This fluid displacement will send a signal to the brain indicating that rotational movement is occuring. However, the vestibular apparatus in the unaffected ear will not be transmitting the same signal because there are no loose otoconia triggering the hair cells abnormally. This resultant mismatch in signals coming from the right and left vestibular systems lead to the sensation of vertigo. This more common condition is known as canalithiasis. Vertigo associated with this condition will be of short duration, even if the person with the condition stays in the provocative position, because the endolymph and otoconia will quickly come to a rest so the hair cells will no longer be displaced and triggering the signal to the brain.

In rare cases, the crystals themselves can adhere to a semicircular canal cupula rendering it heavier than the surrounding endolymph. Upon reorientation of the head relative to gravity, the cupula is weighted down by the dense particles thereby inducing an immediate and maintained excitation of semicircular canal afferent nerves. This condition is termed cupulolithiasis. Vertigo associated with this condition will not resolve until the head is moved out of the provocative position because even when the endolymph comes to a rest, the adhered otoconia will continue to displace the hair cells and trigger the signal of movement to the brain.

It can be triggered by any action which stimulates the posterior semi-circular canal which may be:

- Tilting the head

- Rolling over in bed

- Looking up or under

- Sudden head motion

BPPV may be made worse by any number of modifiers which may vary between individuals:

- Changes in barometric pressure - patients often feel symptoms approximately two days before rain or snow [9]

- Lack of sleep (required amount of sleep may vary widely)

- Stress

Aetiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

The most common cause of BPPV is idiopathic. However, the vestibular system of the inner ear can also undergo degenerative changes as one ages which can attribute to a potential cause of BPPV. Under age 50, head injury is a common cause. Vestibular viruses and Meniere’s disease also play a role. BPPV can also be a result of surgery due to prolonged supine positioning and possible trauma to the inner ear[10].

Risk factors include[2][11][12]:

- Female gender

- falls

- Hypertension (HTN)

- Hyperlipidemia

- Cerebrovascular disease

- Menopause

- Allergies

- Migraine

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Surgical procedure such as a cochlear implant

- Infection

Prevalence [edit | edit source]

- Dizziness is the complaint in 5.6 million clinical visits in the United States per year, and between 17 and 42 percent of these patients are diagnosed with BPPV[13].

- Female to male ratio is 3:1[11]

- The recurrence rate for individuals at one year following initial bout of BPPV is 15% and at 5 years the recurrence rate is 37-50%[14].

- Individuals with a clinical diagnosis of anxiety are 2.7 times more likely to develop BPPV[11].

- Unilateral posterior canal is the most commonly affected canal in BPPV with 90% of all BPPV diagnosis[15].

- Unilateral horizontal canal affects 5-15% of all BPPV diagnosis. Within a horizontal canal diagnosis, 2/3 of the cases are geotropic while 1/3 of the cases are apogeotropic[15].

- Anterior canal affects 1-2% of all BPPV diagnoses, which is the least common[15].

- The lifetime prevalence is 2.4 percent[13].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of BPPV are often transient, with symptoms commonly lasting less than one minute (paroxysmal).[16] Episodes of BPPV can resolve after a few weeks or months, but may reappear at a later time. Screening for BPPV in all people with falls risk, whether dizzy or not, is important to detect all cases of BPPV.[17]

The possible reasons why people test positive for Signs and symptoms may include:[16]

- Vertigo: Spinning sensation (not lightheadedness or feeling off-balance.)

- Short duration (Paroxysmal): Lasts only seconds to minutes (usually less than 60 seconds)[18]

- Positional in onset: only induced by a change in position

- Nausea

- Visual disturbance: It may be difficult to read or see during an attack due to the associated nystagmus.

- Pre-Syncope (feeling faint) or Syncope (fainting)

- Vomiting is uncommon, but possible.

- Loss of balance Symptoms are considered:

- Mild: inconsistent positional vertigo

- Moderate: frequent positional vertigo attacks with disequilibrium between vertigo attacks

- Severe: vertigo with most head movements, which can appear as continuous vertigo[14]. Individuals with BPPV can have symptoms that last days, weeks, months or years before it is resolved[14].

Research suggests there is a definite correlation between cognitive skills and balance in women patients affected with chronic peripheral vestibulopathy[19].

- Signs

- Rotatory (torsional) nystagmus, where the top of the eye rotates towards the affected ear in a beating or twitching fashion

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

There are conditions that appear to more prevalent in patients that experience BPPV, for example:[2][5]

- Meniere's disease

- Vertebral basilar insufficiency

- Migraine

- Multiple sclerosis

- Infection: sinus or ear

- Thyroid problems

- Reduced bone mineral density

- Sudden hearing loss

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Meniere's disease

- Vestibular neuritis

- Labyrinthitis

- Superior canal dehiscence syndrome

- Post-traumatic vertigo

- Anxiety or panic disorders

- Cervicogenic dizziness

- Medication side effects

- Postural hypotension

Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy is not appropriate for unstable vestibular disorders such as

- Meniere's disease

- Uncontrolled migraine

- Perilymph Fistula (PLF)

- Unresolved Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence (SSCD)

- Sudden loss of hearing

- Ringing in one or both ears

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

BPPV can easily be diagnosed and treated through simple clinic-based procedures.[20] In the past, a wide variety of different tests and procedures have been explored for diagnosis of BPPV, but many of these techniques have been discredited in recent years. Currently the primary method of diagnosis involves in-depth subjective screening, followed by physical investigations and diagnostic manoeuvres to confirm BPPV. These methods of diagnosis have been shown to be clinically appropriate, simple to perform, and cost effective.[7] Early diagnosis of BPPV is important and may help improve quality of life for patients and reduce the risk of more serious injury. Techniques may be easily incorporated into routine physiotherapy assessment and should be considered for any patients presenting with symptoms of dizziness and vertigo. The condition is diagnosed from patient history (feeling of vertigo with sudden changes in positions) and by performing a positional test. Different positional test exist. The exact positional test used to confirm the presence of BPPV will depend on which semicircular canal is involved.

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

The subjective assessment is the first step in clinically diagnosing BPPV. Any complaints of dizziness necessitate the taking of a detailed patient history and further investigation of the symptoms.[21] Patient history alone is insufficient to accurately diagnose BPPV, but patient description of vertigo can give a very good indication of the cause.[7] However, people with risk of falls without symptoms of dizziness should be assessed. [17]Clinicians should look out for patients describing sudden severe attacks of vertigo or dizziness, precipitated by head position and movement.[22] The most common movements thought to provoke symptoms are rolling over in bed, extension of the neck to look up, and bending forward.[22] Patients typically describe their vertigo as a rotational or spinning sensation provoked by these movements.[7]

Different studies have aimed to identify and validate useful questions when suspecting a diagnosis of BPPV. There are however no current guidelines for appropriate BPPV screening questions. Some important aspects of the condition have been identified which should be explored to rule out other causes[18]. Clinicians should be asking patients questions regarding:

1. Type of dizziness and vertigo

2. Duration of dizziness and vertigo

3. Precipitating and exacerbating factors

4. Accompanying symptoms

Physical Assessment[edit | edit source]

If details of the subjective assessment and patient history indicate BPPV, then further physical investigation is needed to confirm a diagnosis. Physical diagnosis maneuvers involve a series of movements which aim to provoke nystagmus and symptoms of vertigo. The two diagnostic maneuvers used clinically are the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and the Supine Roll Test. A positive result on either of these tests indicates a diagnosis of BPPV. They also help to distinguish the type of BPPV and identify the ear involved.

Dix Hall Pike[edit | edit source]

The most commonly used test is Dix-Hallpike which assesses involvement of the posterior canal (the most commonly affected semicircular canal).[23] The test involves turning the head 45 degrees to the side being tested and then quickly moving from a seated to a supine position with the head declined 30 degrees below the trunk. The test must be performed quickly to ensure sufficient displacement of the endolymp and otoconia to provoke the expected symptoms. The test is considered positive for canalithiasis of the posterior canal if vertigo is provoked and nystagmus is observed, both of which should be of short-duration for canalithiasis. The direction of the observed nystagmus should be consistent with the canal being assessed. For the posterior canal, nystagmus should be up-beating and torsional in an ipsilateral direction (if testing the affected side. If the left side is affected but the test is performed with the head turned to the right, the nystagmus would be up-beating and torsional to the right).

Horizontal Roll Test[edit | edit source]

This test is to assess the horizontal semicircular canal

- Patient is supine. Examiner flexes the cervical spine 20-30 degrees.

- Examiner quickly rotates the head to the right approximately 45 degrees. Hold for 30 seconds or until nystagmus and/or other symptoms have subsided

- Slowly return patient's head to midline.

- Next, quickly rotate patient's head to the left approximately 45 degrees.Hold for 30 seconds or until nystagmus and/or other symptoms have subsided.

- Slowly return patient's head to midline.

- Test is positive for nystagmus of other symptomatic complaints during the test. The patient may be positive on both sides. If this happens, the side that has more intense symptoms is considered the affected side.<be>

Head Pitch Test (“Bow and Lean” Test)[edit | edit source]

This test is used to assess unilateral horizontal canal BPPV[15]

- Patient is seated

- Examiner first bends the patient’s head forward 30 degrees. Reassess nystagmus. Patient’s nystagmus should disappear because the horizontal canal is now in a true horizontal position.

- Examiner then bends the patient’s head forward to 60 degrees. Reassess nystagmus. A fast paced nystagmus may be present. If the nystagmus is being caused by the otoconia moving, the nystagmus will beat toward the affected ear. If the otoconia is attached to the cupula, the nystagmus will beat towards the unaffected ear.

- Examiner bends the patient’s head backwards 30 degrees. Reassess nystagmus. May see an increase in nystagmus due to the horizontal canal being vertical

The nystagmus associated with BPPV has several important characteristics which differentiate it from other types of nystagmus.

- Positional: the nystagmus occurs only in certain positions

- Latency of onsent: there is a 5-10 second delay prior to onset of nystagmus

- Nystagmus lasts for 5-30 seconds

- Visual fixation does not suppress nystagmus due to BPPV

- Both a rotatory and upbeat vertical components are present

- The nystagmus beats in a geotrophic (top of the eye towards the ground fashion

- Repeated Dix-Hallpike maneuvers cause the nystagmus to fatigue or disappear temporarily

If nystagmus and vertigo are sustained, cupulolithiasis or a potentially more central cause of vertigo should be considered. Patient history and other neurological tests can help to rule out a more serious central cause.

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Research review implies that the posterior and horizontal canal BPPV canalith repositioning maneuvers (Semont, Epley, and Gufoni's maneuvers) are level 1 evidence treatment, and the choice of maneuver (since their efficacy is comparable) is up to the clinician's preferences, failure of the previous maneuver, or movement restrictions of the patient.[26] Two treatments have been found effective for relieving symptoms of posterior canal BPPV:

- Canalith repositioning procedure (Epley maneuver)

- Employs gravity to move calcium build-up that causes the condition

- Can also be performed by trained otolaryngologists, neurologisists, chiropractors or audiologists

- Liberatory or Semont maneuver

Epley Maneuver[edit | edit source]

- Patient starts in long sitting, head rotated 45 degrees to affected side

- Patient rapidly reclined to supine position with neck slightly extended. Hold position for 30 seconds, or until nystagmus and dizziness subside

- Rotate head 90 degrees to opposite side. Hold position for 20 seconds, or until nystagmus and dizziness subside

- Patient rotated 90 degrees from supine to side-lying. Hold position for 20 seconds, or until nystagmus and dizziness subside

- Bring patient up into short-sitting

May need to complete this maneuver 1 to 3 visits complete resolution of symptoms.

Semont Maneuver[edit | edit source]

- Patient sits in short sitting, head rotated 45 degrees towards unaffected ear[14]

- Examiner places one hand under the bottommost shoulder while the other hand supports the neck

- Patient rapidly moves into side-lying to the affected side (face should be oriented towards ceiling). Hold this position for 30 seconds

- Without any head movement, patient is to move to side-lying on opposite side of the body (face oriented towards bed). Hold this position for 30 seconds

Lempert Maneuver[edit | edit source]

Treatment for horizontal/lateral canal BPPV

- Patient lie supine on examination table, affected ear down

- Quickly turn the head 90 degrees towards unaffected side facing up

- Wait 15-20 seconds between each head turn

- Turn the head 90 degrees so affected ear is up

- Have patient tuck arms to chest, roll patient into prone

- Have patient turn on side as you roll their head 90 degrees ( return to original position, affected ear down)

- Reposition patient so that they are facing up into sitting position

Gufoni Maneuver[edit | edit source]

Treatment for horizontal/lateral canal BPPV

- Patient taken from sitting to side-lying on affected or unaffected side

- Geotropic nystagmus: unaffected

- Apogeotropic: affected

- Turn patient head quickly towards ground (45-60 degrees), hold in this position for 2 minutes

- Patient returns to sitting with head maintained in that position

Habituation Techniques[10][edit | edit source]

- Avoid quick spins or movements that provoke vertigo

- Sleep in semi-recumbent position for next 2 nights following Epley's technique (use a recliner or stack of pillows)

- Avoid sleeping on affected side

- Try keep head upright during day and avoid all supine activities

- After being conservative for a week, start to place head (in controlled environments) in vertigo provoking positions

Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises[edit | edit source]

Vestibular rehabilitation exercises are commonly included in the treatment of BPPV and are designed to train the brain to use alternative visual and proprioceptive cues to maintain balance and gait.[31] It has been shown that these exercises improved nystagmus, postural control, movement-provoked dizziness, the ability to perform activities of daily living independently, and levels of distress.[31] While no single vestibular rehabilitation exercise has been shown to reduce the symptoms of BPPV, a program of therapies that can include self-administered repositioning maneuvers, gaze stabilization exercises, falls prevention training, and patient education may be beneficial in reducing the symptoms of BPPV and improve quality of life.[32]

The evidence supporting the efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation exercises in reducing symptoms of BPPV is lacking.[32] Steenerson et al.[33], found that Epley’s maneuver administered by a health care practitioner was a better treatment technique than vestibular rehabilitation exercises. Vestibular exercises were, however deemed to be better than no treatment at all. No single form of vestibular rehabilitation exercise has been found to be superior and exercises appear to have a greater effect when performed together, rather than as single exercises alone.[32]

Cawthorne-Cooksey Exercises[edit | edit source]

The Cawthorne-Cooksey exercises aim to relax the neck and shoulder muscles, train eyes to move independently of the head, and to practice balance and head movements that cause dizziness.[34] The exercises consist of a series of eye, head, and body movements, in increasing difficulty, which aim to provoke symptoms.[32] The goal of these exercises is to fatigue the vestibular response and force the central nervous system to compensate by habituation to the stimulus.[32]

A video description of the Cawthorne-Cooksey Exercises[edit | edit source]

Brandt-Daroff Exercises[edit | edit source]

The Brandt-Daroff exercises are a series of particle repositioning exercises that can be performed without a qualified health professional present and are easily taught to the patient.[34] While beneficial, these exercises are more time consuming than other forms of treatment. They are completed by the patient in bed, 3 sets a day for 2 weeks and aim to help reduce the chance of reoccurrence of BPPV and promote the loosening of canaliths.[32] Radke et al.[36] found that when these exercises are performed as the only form of treatment, they were successful at relieving the symptoms of BPPV in only 25% of individuals after one week of administration. The Brandt-Daroff exercises have been found to be a beneficial adjunct treatment in the symptomatic relief of BPPV.[32]

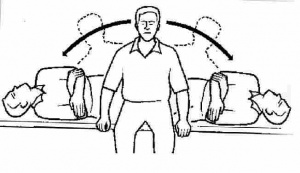

The Brandt-Daroff exercises may be summarized in the following steps (see Figure 7):

- Step 1 - Have the patient sit on the edge of the bed and turn their head 45° to one side

- Step 2 - Quickly have the patient lie down on the opposite side that their head is facing

- Step 3 - Have the patient hold this position for 30 seconds

- Step 4 - Return to the sitting position

- Step 5 - Repeat steps 1-4 while facing the opposite direction, alternating until 6 repetitions have been completed.[34]

A video demonstration of the Brandt-Daroff Exercises[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

BPPV is a benign diagnosis so treatment is not always needed. Occasionally, BPPV can resolve itself with no intervention[38].

Surgery[38]:

- Singular Nerve Neurectomy

- Posterior Canal Occlusion

Medications:

- There are no medications that directly treat BPPV

- Antivert, Meclizine and vestibular suppressants can be prescribed to treat dizziness, nausea and other symptoms related to BPPV[39]

Drug treatments are not presently recommended for BPPV and bilateral vestibular paresis.

- Prophylactic agents (L-channel calcium channel antagonists, tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers) are the mainstay of treatment for migraine-associated vertigo.

- In individuals with stroke or other structural lesions of the brainstem or cerebellum, an eclectic approach incorporating trials of vestibular suppressants and physical therapy is recommended.

- Psychogenic vertigo occurs in association with disorders such as panic disorder, anxiety disorder and agoraphobia. Benzodiazepines are the most useful agents here.

- Undetermined and ill-defined causes of vertigo make up a large remainder of diagnoses. An empirical approach to these patients incorporating trials of medications of general utility, such as benzodiazepines, as well as trials of medication withdrawal when appropriate, physical therapy and psychiatric consultation is suggested[40].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are many outcome measures used when treating patients with vertigo, such as:[39][41]

- Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI)

- Dynamic Gait Index (DGI)

- Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction in Balance (CTSIB)

- Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale

- Vertigo Intensitu

- Vertigo Frequency

- Vestibular Disorders Activities of Daily Living Scale

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (for the clinician and patient)

- Clinical Practice Guideline: BPPV (for the clinician)

- Effectiveness of Particle Repositioning Maneuvers in the Treatment of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: A Systematic Review from PT Journal May 2010

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shim, D. B., Song, C. E., Jung, E. J., Ko, K. M., Park, J. W., & Song, M. H. (2014). Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo with Simultaneous Involvement of Multiple Semicircular Canals.Korean Journal of Audiology,18(3), 126. doi:10.7874/kja.2014.18.3.126

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Ogun OA, Janky KL, Cohn ES, Büki B, Lundberg YW. Gender-Based Comorbidity in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105546.

- ↑ Timothy C. Hain, MD, BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONAL VERTIGO, site: http://www.dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/bppv/bppv.html , Page last modified: February 3, 2013

- ↑ Sonia Sandhaus, Stop the spinning: Diagnosing and managing vertigo. Nurse Practitioner. 2002 Aug 1;27(8): 11-23.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Maia FZE. New treatment strategy for apogeotropic horizontal canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Audiology Research. 2016;6(2). doi:10.4081/audiores.2016.163.

- ↑ UPMC. What Is Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo? . Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1AfvNsaQnTE [last accessed 26/8/2022]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Neil Bhattacharyya, Reginald F. Baugh, Laura Orvidas, David Barrs, Leo J. Bronston, Stephen Cass, Ara A. Chalian, Alan L. Desmond, Jerry M. Earll, Terry D. Fife, Drew C. Fuller, MPH, James O. Judge, Nancy R. Mann, Richard M. Rosenfeld, Linda T. Schuring, Robert W. P. Steiner, Susan L. Whitney, and Jenissa Haidari. Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2008, 139, S47-S81

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lorne S. Parnes, Sumit K. Agrawal and Jason Atlas. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. September 30, 2003; 169 (7)

- ↑ Korpon JR, Sabo RT, Coelho DH. Barometric pressure and the incidence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. American Journal of Otolaryngology. 2019 Sep 1;40(5):641-4. [1]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 American Hearing Research Foundation: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). http://www.american-hearing.org/disorders/benign-paroxysmal-positional-vertigobppv/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Chen, Z., Chang, C., Hu, L., Tu, M., Lu, T., Chen, P., & Shen, C. (2016). Increased risk of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in patients with anxiety disorders: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study.BMC Psychiatry,16(1). doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0950-2

- ↑ Gaur S, Awasthi SK, Bhadouriya SKS, Saxena R, Pathak VK, Bisht M. Efficacy of Epley’s Maneuver in Treating BPPV Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. International Journal of Otolaryngology. 2015;2015:1-5. doi:10.1155/2015/487160.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Bhattacharyya N, Baugh R, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston L, Haidari J, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology--Head And Neck Surgery: Official Journal Of American Academy Of Otolaryngology-Head And Neck Surgery, 2008, Nov; 139(5 Suppl 4): S47-S81

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Hornibrook, J. (2011). Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): History, Pathophysiology, Office Treatment and Future Directions.International Journal of Otolaryngology,2011, 1-13. doi:10.1155/2011/835671

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Balatsouras DG, Koukoutsis G, Ganelis P, Korres GS, Kaberos A. Diagnosis of Single- or Multiple-Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo according to the Type of Nystagmus. International Journal of Otolaryngology. 2011;2011:1-13. doi:10.1155/2011/483965.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Musat J. The Clinical Characteristics and Treatment of Benign Paraoxysmal Positional Vertigo in the Elderly. Romanian Journal of Neurology 2010;9(4):189-192.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Susan Hyland, Lyndon J. Hawke & Nicholas F. Taylor (24 Feb 2024):Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo without dizziness is common in people presenting to falls clinics,Disability and Rehabilitation DOI:10.1080/09638288.2024.2320271

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Strupp M, Dieterich M, Brandt T. The Treatment and Natural Course of Peripheral and Central Vertigo. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International . 110(29):505-516.

- ↑ Coelho AR, Perobelli JL, Sonobe LS, Moraes R, de Carneiro Barros CG, de Abreu DC. Severe Dizziness Related to Postural Instability, Changes in Gait and Cognitive Skills in Patients with Chronic Peripheral Vestibulopathy. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology. 2020 Jan;24(01):e38-45.

- ↑ Balasouras DG, Koukoutsis G, Ganelis P, Korres GS, Kaberos A. Diagnosis of single- or multiple-canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo according the type of nystagmus. International Jounral of Otalaryngology. 2011; 1-13.

- ↑ Strupp M and Brandt T. Diagnosis and treatment of vertigo and dizziness. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008; 105(10): 173-180.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Parnes L, Agrawal S, Atlas J. Diagnosis and Management of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) 2003; 169(7): 681-693.

- ↑ Lorne S. Parnes, Sumit K. Agrawal and Jason Atlas. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. September 30, 2003; 169 (7)

- ↑ Ascension Via Christi. Dix Hallpike Maneuver. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-uVlxWDu4k [last accessed 14/7/2022]

- ↑ Ascension Via Christi. Supine Roll Maneuver. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3SGJfjwJaw [last accessed 14/7/2022]

- ↑ Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019 Dec 5;21(12):66. doi: 10.1007/s11940-019-0606-x.

- ↑ AquacarePT. How to perform the epley maneuver at home for BPPV. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtJB5Vx7Xqo [last accessed 26/8/2022]

- ↑ Michigan Medicine. Liberatory Semont Maneuver for Right BPPV. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A72UjulJSzE&t=2s [last accessed 26/8/2022]

- ↑ Ascension Via Christi. Barbeque Roll Lempert maneuver. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ufD_tcSx5dQ [last accessed 26/8/2022]

- ↑ Gelreziekenhuizen. Gufoni manoeuvre. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gTkZs0EcREY [last accessed 26/8/2022]

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Swartz R, Longwell P. Treatment of Vertigo. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2005; 71: 1115-1122

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2008;139(5):S47-S81.

- ↑ Steenerson R, Cronin G. Comparison of the canalith repositioning procedure and vestibular habituation training in forty patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. American Academy of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. 1996; 114: 61-64.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Brain and Spine Foundation. Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises: A Fact Sheet for Patients and Carers. http://www.brainandspine.org.uk/information/publications/brain_and_spine_booklets/vestibular_rehabilitation_exercises/index.html (Accessed October 12 2012).

- ↑ Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises. [Video: Website]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NXyg9n3nFQk. 2011. (Accessed October 30 2012).

- ↑ Radke A, Neuhauser H, von Brevern M, Lempert T. A modified Epley’s procedure for self-treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Neurology. 1999; 53: 1358-1360.

- ↑ Brandt-Daroff Exercises for BPPV Dr. Michael Teixido. [Video: Website]. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTZfIv165sY. 2011. (Accessed October 30 2012).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Nguyen- Huynh, A. T., MD PhD. (2012). Evidence-Based Practice: Management of Vertigo.Otolaryngeol Clin North Am. ,45(5), 925-940. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2012.06.001

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Cohen, H. S., & Sangi-Haghpeykar, H. (2010). Canalith repositioning variations for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery,143(3), 405-412. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.022

- ↑ Hain TC, Uddin M., Pharmacological treatment of vertigo.CNS Drugs. 2003;17(2):85-100.

- ↑ Maslovara, S. (2014). Importance of accurate diagnosis in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) therapy.Med Glas,11(2).