Breathing Pattern Disorders

Original Editor - Leon Chaitow

Top Contributors - Rachael Lowe, Leon Chaitow, Admin, Kim Jackson, Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt, Wanda van Niekerk, Khloud Shreif, Fasuba Ayobami, WikiSysop, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Ajay Upadhyay, Marleen Moll, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Evan Thomas, Scott Buxton and Venus Pagare

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Breathing Pattern Disorders (BPDs) or Dysfunctional Breathing are abnormal respiratory patterns specifically related to over-breathing. They range from simple upper chest breathing to, at the end of the scale, hyperventilation (HVS).[1]

Dysfunctional breathing (DB) is defined as chronic or recurrent conditions where "the normal biomechanical pattern of breathing is disrupted, resulting in dyspnea and associated non-respiratory symptoms that cannot be fully explained by disease pathophysiology". [2] It is not a disease process, but rather alterations in breathing patterns that interfere with normal respiratory processes. BPD can, however, co-exist with diseases such as COPD or heart disease. [3][4]

BPDs are whole-person problems as it can cause symptoms with no apparent organic cause and are a risk factor for the development of the mind, muscles, and metabolism dysfunction.[5] [6] A positive correlation was found between breathing pattern disorders and premenstrual syndrome,[7] chronic fatigue,[8] neck, back and pelvic pain,[9][10] fibromyalgia[11] [12] and some aspects of anxiety and depression.[1][13]

BPD is considered an umbrella term for different, abnormal patterns of breathing. One classification includes the following: [14]

- Mouth breathing

- Apical predominance

- Structural abnormality

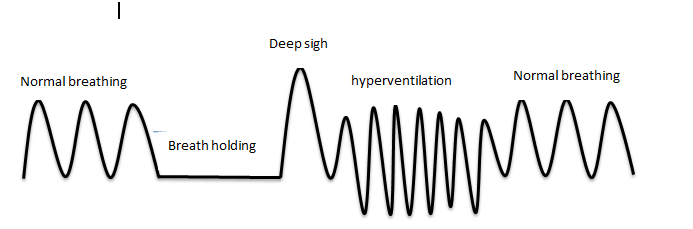

The figure above describes normal and abnormal breathing patterns. Breath-holding: breath that is held for a while. A deep sigh is a deep inspiration. Hyperventilation: increase in respiratory rate (RR)/tidal volume.[15]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The human respiratory system is located in the thorax. The thoracic wall consists of skeletal and muscular components, extending between the 1st rib superiorly and the 12th rib, the costal margin and the xiphoid process inferiorly.[16] The respiratory system can be classified in function and anatomy. Functionally, it is divided into two zones. The conducting zone extends from the nose to the bronchioles and serves as a pathway for the conduction of inhaled gases. The respiratory zone is the second area and is the site for gaseous exchange. It comprises of alveolar duct, alveolar sac and alveoli. Anatomically, it is divided into the upper and lower respiratory tract. The upper respiratory tract starts proximally from the nose and ends at the larynx, while the lower respiratory tract continues from the trachea to the alveoli distally.[17]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

In the general population, 8 to 10% of people are diagnosed with breathing pattern disorder (BPD).[19] [14] It is more common in women. In children and adolescents, the presence of this condition varies from 2.5% to 21%. It is unknown what proportion of the general pediatric population is affected due to a lack of standardized definitions and recognition of its importance.[20][21]

As many as 36% of adults with asthma and 25% of adolescents have BPD.[14]Females with asthma will more likely suffer from this condition than males with asthma. The risk of developing BPD increases for patients with difficult-to-treat asthma and can affect up to 47% of individuals. One-third of patients with COPD experience breathing pattern disorder. There are more likely to be females, obese, older, and with frequent exacerbations of COPD.[14]

BPD is also common in patients with anxiety disorder and mental health conditions (depression, personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder), where anxiety affects the biomechanics of breathing.[22]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorders occur when ventilation exceeds metabolic demands, resulting in symptom-producing haemodynamic and chemical changes. Hyperventilation, one of the patterns of BPD, usually requires an upper chest breathing to draw in extra air that is needed. It can result in hypocapnia, a deficiency of carbon dioxide in the blood which can lead to respiratory alkalosis and, eventually, hypoxia, or the reduction of oxygen delivery to tissue.[23] [24] However, hypocapnia, when present alone, is not sufficient to diagnose hyperventilation. There is enough evidence that hyperventilation is not a standalone condition. [25](Read more on: The physiology of breathing well)

As well as having a marked effect on the body's biochemistry, BPDs can influence emotions[26], circulation, digestive function, and musculoskeletal structures involved in the respiratory process. A sympathetic state and a subtle yet relatively constant fight-or-flight state become prevalent. Respiratory alkalosis, reduction in tissue oxygenation, smooth muscle constriction, increased pain, and development of myofascial trigger points are all symptoms capable of changing skeletal muscles' motor control. In addition, gastrointestinal or cardiac problems can be present as BPDs are capable of producing symptoms that mimic pathological processes.[3][4]

Musculoskeletal imbalances often exist in patients with BPDs. These may result from a pre-existing contributing factor or may be caused by the dysfunctional breathing pattern.[27] Types of imbalances include the followings:[27]

- loss of thoracic mobility

- overuse/tension in accessory respiratory muscles

- dysfunctional postures that affect the movement of the chest wall,

- exacerbation of poor diaphragmatic descent.

A 2018 study by Zafar and colleagues found that changes in the head-neck position immediately impact respiratory function, including reduced diaphragm strength.[28] When these changes become habitual (i.e. with regular computer or phone use), a forward head position develops. Forward head posture can cause stiffness, neck and upper back pain, shallow breathing, and changes in breathing patterns.[28]

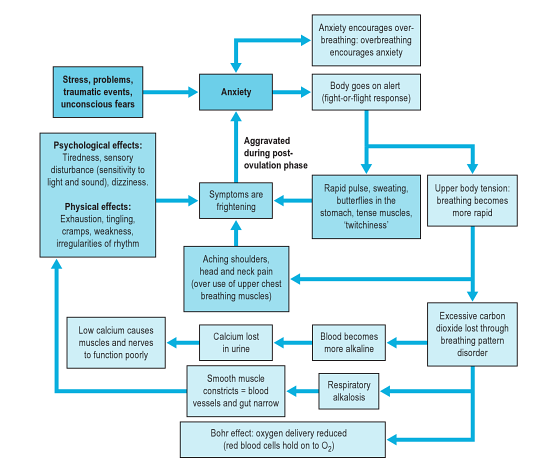

This diagram below (from [29]) shows the stress-anxiety-breathing flow chart demonstrating multiple possible effects and influences of breathing pattern disorders.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Breathing pattern disorders manifest differently based on the individual. Some people may exhibit high levels of anxiety/fear, whereas others have more musculoskeletal symptoms, chronic pain and fatigue.[27] Over 30 possible symptoms have been described in relation to BPDs/HVS.[27]

Typical symptoms can include:

- Frequent sighing and yawning

- Breathing discomfort

- Disturbed sleep

- Erratic heartbeats

- Feeling anxious and uptight

- Pins and needles

- Upset gut/nausea

- Clammy hands

- Chest pains

- Shattered confidence

- Tired all the time

- Achy muscles and joints

- Dizzy spells or feeling spaced out

- Irritability or hypervigilance

- Feeling of 'air hunger' (i.e. a sense of not getting enough air)

- Breathing discomfort

- There may also be a correlation between BPD and low back pain.[30]

Classification[edit | edit source]

As dysfunctional breathing (DB) mimic other severe conditions, it isn't easy to detect the prevalence of BPD/DB and the management of BPD. In recent years, researchers suggested an alternative classification for BPD/DB.[15]

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Barker and Everard[31] | |

| Thoracic DB | Upper chest wall activity with or without accessory muscles activation, sighing and irregular respiratory pattern. |

| Extrathoracic DB | Upper airway impairment manifested in combination with breathing pattern disorders (e.g., vocal cord dysfunction). |

| Functional DB (a subdivision of thoracic and extrathoracic DB) | No structural or functional alterations directly associated with the symptoms of DB (e.g., phrenic nerve palsy, myopathy, and diaphragmatic eventration (one leaf of diaphragm elevated compared to another leaf ). |

| Structural DB (a subdivision of thoracic and extrathoracic DB) | Primarily associated with anatomical or neurological alterations (e.g., subglottic stenosis and unilateral cord palsy). |

| Boulding et al[32] | |

| Hyperventilation syndrome | Associated with respiratory alkalosis or independent of hypocapnia. |

| Periodic deep sighing | Associated with sighing, irregular breathing pattern and may overlap with hyperventilation. |

| Thoracic dominant breathing | Associated with higher levels of dyspnoea. It can manifest more often in somatic diseases where there’s a need to increase ventilation. |

| Forced abdominal expiration | When there is inappropriate and excessive abdominal muscle contraction to assist expiration. Occurs as a normal physiologic adaptation in COPD and pulmonary hyperinflation. |

| Thoracoabdominal asynchrony | Ineffective respiratory mechanics that happen due to delay between the rib cage and abdominal contraction occurs as a normal physiological response in upper airway obstruction. |

Co-existing Problems[edit | edit source]

Asthma and COPD[edit | edit source]

During an acute asthma attack, patients adopt a breathing pattern that is similar to the pattern seen in BPD:

- hyper-inflated

- rapid

- upper chest

- shallow[27]

Therefore, patients with chronic asthma may be more likely to develop BPDs, which may contribute to symptoms.[27] [33] Thus, after an acute attack, it is important to re-establish abdominal/nose breathing patterns and normalised CO2 levels.[29] Exercise is commonly considered a trigger for asthma. However, some patient's breathlessness may be due to hyperinflation and increased respiratory effort from faulty breathing patterns.[27]

Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS)[edit | edit source]

Chronic mouth breathing often occurs with CRS and can, therefore, result in a chronic breathing pattern dysfunction. Saline nasal rises and eucalyptus steam inhalations can ease sinus congestion and restore nasal breathing. Because CRS is common in HVS/BPD patients, restoring nose breathing is a high priority in breathing retraining programmes.[29]

Chronic Pain[edit | edit source]

Chronic pain and chronic hyperventilation often co-exist. Pain can cause an increase in respiratory rates generally. Moreover, patients with abdominal or pelvic pain often splint their abdominal muscles, which results in upper chest breathing. When treating patients with chronic pain, it is important to achieve nose/abdominal breathing and promote relaxation.[29]

Hormonal Influences[edit | edit source]

Progesterone is a respiratory stimulant. As it peaks in the post-ovulation phase, it may drive PaCO2 levels down. These levels further reduce during pregnancy.[29] It has been found that patients with PMS can benefit from breathing retraining and education to reduce any symptoms related to HVS.[29] Similarly, peri/postmenopausal women who cannot take HRT have been shown to benefit from breathing retraining to improve sleep and reduce hot flushes.[29]

Assessment and Management[edit | edit source]

For information on the Assessment of Breathing Pattern Disorders, click here

For information on the Management of Breathing Pattern Disorders, click here.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lum LC. Hyperventilation syndromes in medicine and psychiatry: a review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1987 Apr;80(4):229-31..

- ↑ Ionescu MF, Mani-Babu S, Degani-Costa LH, Johnson M, Paramasivan C, Sylvester K, Fuld J. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the assessment of dysfunctional breathing. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021 Jan 27;11:620955.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Sueda S, Kohno H, Fukuda H, Ochi N, Kawada H, Hayashi Y, Uraoka T. Clinical impact of selective spasm provocation tests: comparisons between acetylcholine and ergonovine in 1508 examinations. Coron Artery Dis. 2004 Dec;15(8):491-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ajani AE, Yan BP. The mystery of coronary artery spasm. Heart, Lung and circulation. 2007 Feb 1;16(1):10-5.

- ↑ Peters, D. Foreword In: Recognizing and Treating Breathing Disorders. Chaitow, L., Bradley, D. and Gilbert, C. Elsevier, 2014

- ↑ Bradley H, Esformes J. Breathing pattern disorders and functional movement. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Feb;9(1):28-39.

- ↑ Ott HW, Mattle V, Zimmermann US, Licht P, Moeller K, Wildt L. Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome may be caused by hyperventilation. Fertility and sterility. 2006 Oct 1;86(4):1001-e17.

- ↑ Nixon PG, Andrews J. A study of anaerobic threshold in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Biological Psychology. 1996;3(43):264.

- ↑ Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. Disorders of breathing and continence have a stronger association with back pain than obesity and physical activity. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2006 Jan 1;52(1):11-6.

- ↑ Haugstad GK, Haugstad TS, Kirste UM, Leganger S, Wojniusz S, Klemmetsen I, Malt UF. Posture, movement patterns, and body awareness in women with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2006 Nov 1;61(5):637-44.

- ↑ Naschitz JE, Mussafia-Priselac R, Kovalev Y, Zaigraykin N, Elias N, Rosner I, Slobodin G. Patterns of hypocapnia on tilt in patients with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, nonspecific dizziness, and neurally mediated syncope. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2006 Jun 1;331(6):295-303.

- ↑ Dunnett AJ, Roy D, Stewart A, McPartland JM. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia in women may be influenced by menstrual cycle phase. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2007 Apr 1;11(2):99-105.

- ↑ Han JN, Stegen K, De Valck C, Clement J, Van de Woestijne KP. Influence of breathing therapy on complaints, anxiety and breathing pattern in patients with hyperventilation syndrome and anxiety disorders. Journal of psychosomatic research. 1996 Nov 1;41(5):481-93.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Denton E, Bondarenko J, Hew M. Breathing pattern disorder. Complex Breathlessness (ERS Monograph). Sheffield, European Respiratory Society. 2022 Sep 1:109-22.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Vidotto LS, Carvalho CR, Harvey A, Jones M. Dysfunctional breathing: what do we know?. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2019;45(1).

- ↑ Kennedy JW (2012). Clinical Anatomy Series‐Lower Respiratory Tract Anatomy. Scottish Universities Medical Journal.1 (2).p174‐179

- ↑ Patwa A, Shah A. Anatomy and physiology of respiratory system relevant to anaesthesia. Indian Journal of anaesthesia. 2015 Sep;59(9):533.

- ↑ Osmosis. Anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fVoz4V75_E[last accessed 14/4/2020]

- ↑ Thomas M1, McKinley RK, Freeman E, Foy C, Price D.The prevalence of dysfunctional breathing in adults in the community with and without asthma. Prim Care Respir J. 2005 Apr;14(2):78-82.

- ↑ Barker N, Thevasagayam R, Ugonna K, Kirkby J. Pediatric dysfunctional breathing: proposed components, mechanisms, diagnosis, and management. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2020 Jul 16;8:379.

- ↑ Barker NJ, Jones M, O'Connell NE, Everard ML. Breathing exercises for dysfunctional breathing/hyperventilation syndrome in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(12).

- ↑ Meuret AE, Ritz T. Hyperventilation in panic disorder and asthma: empirical evidence and clinical strategies. Int J Psychophysiol. 2010 Oct;78(1):68-79.

- ↑ Palmer BF. Evaluation and treatment of respiratory alkalosis. American journal of kidney diseases. 2012 Nov 1;60(5):834-8.8.

- ↑ Jensen FB. Red blood cell pH, the Bohr effect, and other oxygenation‐linked phenomena in blood O2 and CO2 transport. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2004 Nov;182(3):215-27.

- ↑ Hornsveld HK, Garssen B, Dop MJ, van Spiegel PI, de Haes JC. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of the hyperventilation provocation test and the validity of the hyperventilation syndrome. Lancet. 1996 Jul 20;348(9021):154-8.

- ↑ van Dixhoorn J 2007. Whole-Body breathing: a systems perspective on respiratory retraining. In: Lehrer P et al. (Eds.) Principles and practice of stress management. Guilford Press. NY pp. 291–332

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 CliftonSmith T, Rowley J. Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Physical therapy reviews. 2011 Feb 1;16(1):75-86.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Zafar H, Albarrati A, Alghadir AH, Iqbal ZA. Effect of Different Head-Neck Postures on the Respiratory Function in Healthy Males. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4518269.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 Chaitow, L., Bradley, D. and Gilbert, C. Recognizing and Treating Breathing Disorders. Elsevier, 2014

- ↑ McLaughlin L, Goldsmith CH, Coleman K. Breathing evaluation and retraining as an adjunct to manual therapy Man Ther. 2011 Feb;16(1):51-2.

- ↑ Barker N, Everard ML. Getting to grips with ‘dysfunctional breathing’. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2015 Jan 1;16(1):53-61.

- ↑ Boulding R, Stacey R, Niven R, Fowler SJ. Dysfunctional breathing: a review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review. 2016 Sep 1;25(141):287-94.

- ↑ Sedeh FB, Von Bülow A, Backer V, Bodtger U, Petersen US, Vest S, Hull JH, Porsbjerg C. The impact of dysfunctional breathing on the level of asthma control in difficult asthma. Respiratory Medicine. 2020 Mar 1;163:105894.