Clostridium Difficile Infection CDI

Original Editors - John Hardy from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - John Hardy, Lucinda hampton, Reem Ramadan, Elaine Lonnemann, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Oyemi Sillo, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya and Nupur Smit Shah

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Clostridium Difficile Infections (CDI) are considered one of the most significant nosocomial infections which affect all hospitals worldwide. Clostridium difficile (C. Difficile) is an anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming bacillus bacteria that can cause colitis, a serious inflammation of the colon. Infections from C. difficile often start after over-taking antibiotics and can sometimes be life-threatening[1]. This rode shaped bacterium exists in vegetative or spore form and can survive harsh environments and common sterilization techniques. Clostridium difficile is resistant to ultra-violent light, high temperatures, and antibiotics.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) has become a serious medical and epidemiological problem with approximately 5% of adults and 15 to 70% of children being colonized by C. difficile and the colonization prevalence further increases with hospitalized patients and patients in nursing homes[3]. Also, patients above the age of 65 are more at risk at developing CDI than younger patients[4]. The incidence of CDIs also depends on the length of the hospitalization period where during the first few days of hospitalization the risk is between 2.1 to 20% and longer periods of hospitalization increase the risk to up to 45.4% of getting CDI[5]. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) C. difficile caused half a million infections and resulted in 15,000 deaths in a single year[6]. Furthermore, according to a study the risk of CDI increases when the patient has co-morbidities where more than 63% of patients with CDIs were immunosuppressed[7] and according to another study conducted by Oxford University the incidence of CDI is high ranging between 6 and 33% with immunosuppressed patients with cancer, HIV and solid organ transplant recipients[8]. Prevention, proper diagnosis and effective treatment are necessary to reduce the risk for the patients, deplete the spreading of infection and diminish the probability of recurrent infection.

Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

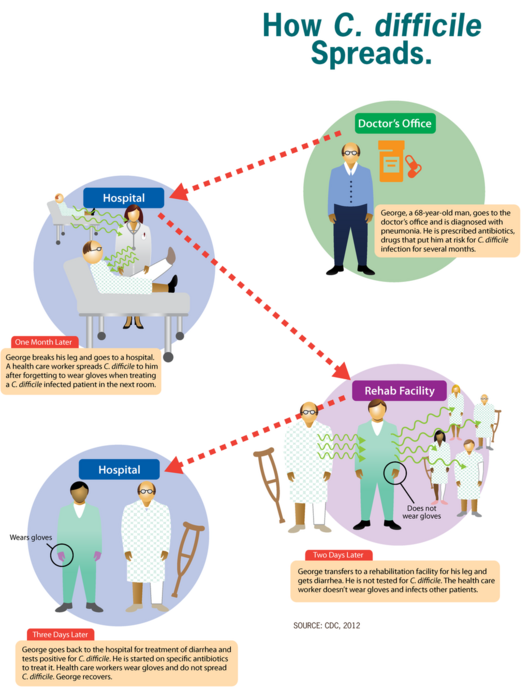

The infection with C. difficile occurs as a result of spore transmission. Spores are transmitted through the fecal-oral route, can survive up to several months and the pathogen is found all around us, being in the air, water, soil, and in the feces of humans and animals. In addition to that, the incubation period of this pathogen may be up to 3 days and is mostly individual-dependent[9].

The main protective barrier against CDI is the normal intestinal flora so this bacterium does not usually cause problems for people who are healthy[10]. Patients who take antibiotic treatment have disruptions in their intestinal flora and are at higher risk of developing CDI[11]. After reaching the intestine, primary bile acids play an important role in the induction of C. difficile spore germination while the secondary ones inhibit it. This leads to changes in the fecal content of bile acids where normally there is a high concentration of secondary bile acids in healthy patients while with patients with CDI, there's a high concentration of primary bile acids[12]. When this balance is disrupted, C. difficile starts to colonize the large intestine and the infection begins.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The clinical state of CDI is heterogeneous and varies from mild to life-threatening. Some of the symptoms experienced include:

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- Fever

- Stomach tenderness or pain

- Weakness

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea[13]

In the most severe clinical presentation of CDI, symptoms are more life-threatening and include:

- Severe diarrhea

- Severe cramping

- Fever

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite/ weight loss

- Dehydration

- Rapid heart rate

- Abdominal distension

- Hypoalbuminemia with peripheral edema

- Circulatory shock

In addition to other severe symptoms like peritonitis, septicemia, perforation of the colon, kidney failure, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, intestinal paralysis and megacolon[14].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

For definitive diagnosis, a stool sample must be collected. Tests include:

- Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) which detects C. difficile toxins

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT)

- Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) which detects C. difficile antigens

- Cell Cytotoxicity Assay Test (CYTA) [15]

In some cases, endoscopic evaluation is useful and is normally not performed with patients with uncomplicated CDI usually confirmed with immunological tests[16]. An abdominal X-ray may also be ordered in order to check for distended bowel loops, often with wall thickening[17]. In addition to that, a computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis and abdomen may be ordered to check for the presence of megacolon, bowel perforation and other findings to check if a surgical intervention is needed[18].

Management[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of CDIs should start only when the patient experiences symptoms. Some of the treatment options include:

- Metronidazole is the first-line drug in non-severe CDI while vancomycin is the drug of choice for severe CDI[19]

- Probiotics: used to help restore a healthful balance in the intestine. Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii), a natural yeast, can reduce recurring C. difficile infections when a person takes it together with antibiotics but there aren't enough studies proving their efficiency in preventing or treating CDI [14]

- Surgery: If symptoms are severe, or if there is organ failure or perforation of the lining of the abdominal wall, it may be necessary to surgically remove the affected part of the colon.

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): Medical professionals are now using fecal transplants in recurrent cases of C. difficile infection. A healthcare provider will transfer bacteria from a healthy person’s colon into the colon of a person with C. difficile[20].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

C. difficile infections are primarily managed through pharmaceutical therapy and associated medical treatments. The therapist should take an active role in infection control and prevention measures whenever working with these patients. Infection control measures include: donning gloves and gowns prior to entering patients room, washing hands with soap and water upon departure, treating patients in a private room and educating visitors on proper hygiene measures. Routine environmental screening and use of chlorine-containing cleaning agents is also recommended.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Smits WK, Lyras D, Lacy DB, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ. Clostridium difficile infection. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2016 Apr 7;2(1):1-20.

- ↑ Cecil J. Clostridium difficile: Changing Epidemiology, Treatment and Infection Prevention Measures. Current Infectious Disease Reports [serial online]. December 2012;14(6):612-619. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 17, 2014

- ↑ Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015 Apr 16;372(16):1539-48.

- ↑ Czepiel J, Kędzierska J, Biesiada G, Birczyńska M, Perucki W, Nowak P, Garlicki A. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infection: results of a hospital-based study in Krakow, Poland. Epidemiology & Infection. 2015 Nov;143(15):3235-43.

- ↑ Hung YP, Lin HJ, Wu TC, Liu HC, Lee JC, Lee CI, Wu YH, Wan L, Tsai PJ, Ko WC. Risk factors of fecal toxigenic or non-toxigenic Clostridium difficile colonization: impact of Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and prior antibiotic exposure. PloS one. 2013 Jul 25;8(7):e69577.

- ↑ Medical news today What to know about Clostridium difficile Available:https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/172329#what-is-c-difficile (accessed 12.5.2022)

- ↑ Acheson ES, Galanis E, Bartlett K, Klinkenberg B. Climate Classification System–Based Determination of Temperate Climate Detection of Cryptococcus gattii sensu lato. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2019 Sep;25(9):1723.

- ↑ Revolinski SL, Munoz-Price LS. Clostridium difficile in immunocompromised hosts: a review of epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and prevention. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019 May 30;68(12):2144-53.

- ↑ McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY et al (1989) Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 320:204–210

- ↑ Allegretti JR, Kearney S, Li N, Bogart E, Bullock K, Gerber GK, Bry L, Clish CB, Alm E, Korzenik JR. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection associates with distinct bile acid and microbiome profiles. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2016 Jun;43(11):1142-53.

- ↑ Rineh A, Kelso MJ, Vatansever F, Tegos GP, Hamblin MR. Clostridium difficile infection: molecular pathogenesis and novel therapeutics. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2014 Jan 1;12(1):131-50.

- ↑ Kochan TJ, Somers MJ, Kaiser AM, Shoshiev MS, Hagan AK, Hastie JL, Giordano NP, Smith AD, Schubert AM, Carlson Jr PE, Hanna PC. Intestinal calcium and bile salts facilitate germination of Clostridium difficile spores. PLoS pathogens. 2017 Jul 13;13(7):e1006443.

- ↑ Johnson S, Clabots CR, Linn FV, Olson MM, Peterson LR, Gerding DN. Nosocomial Clostridium difficile colonisation and disease. The Lancet. 1990 Jul 14;336(8707):97-100.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE, Dubberke ER, Garey KW, Gould CV, Kelly C, Loo V. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clinical infectious diseases. 2018 Apr 1;66(7):e1-48.

- ↑ Simor AE. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infection in long‐term care facilities: A review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010 Aug;58(8):1556-64.

- ↑ Hookman P, Barkin JS. Clostridium difficile associated infection, diarrhea and colitis. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2009 Apr 4;15(13):1554.

- ↑ Vaishnavi C. Clinical spectrum & pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile associated diseases. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2010 Apr 1;131(4):487-99.

- ↑ Paláu-Dávila L, Lara-Medrano R, Negreros-Osuna AA, Salinas-Chapa M, Garza-González E, Gutierrez-Delgado EM, Camacho-Ortiz A. Efficacy of computed tomography for the prediction of colectomy and mortality in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2016 Dec 1;12:101-5.

- ↑ Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ, Committee. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clinical microbiology and infection. 2014 Mar;20:1-26.

- ↑ Shin YJ, Lee BJ. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation as a Treatment of Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Heading?. The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr 1;69(4):203-5.