Diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy

Original Editor - Roelie Wolting

Top Contributors - Michelle Lee, Laura Ritchie, Naomi O'Reilly, Roelie Wolting, Kim Jackson, Admin, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Evan Thomas, Rucha Gadgil, Amanda Ager and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The information on this page has developed for you from the expert work of Roelie Wolting alongside the Enablement Cerebral Palsy Project and Handicap International Group.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosing Cerebral Palsy takes time and is usually not made until the brain is fully developed. The age of a child when diagnosed can vary between the ages of two to five years old. Exceptions do exist but this is usually in severe cases when the child may be diagnosed soon after birth. Although in general the average age of diagnosis for a child with spastic diplegia, a very common form of cerebral palsy, is 18 months.

There are no definitive tests that confirm or rule-out cerebral palsy. The process of diagnosing cerebral palsy involves monitoring the child's development and watching for possible signs of impairment. Often, parents are first to notice their child has missed one of the age-appropriate developmental milestones, like rolling, crawling, sitting and walking. In many countries there are systems of monitoring the growth, development and health of children under 5 years. This may be where the first signs of cerebral palsy are identified.

Indications for monitoring[edit | edit source]

There are guidelines on meeting developmental milestones which are usually monitored by health care professionals so if achievement of a milestone is late, this can indicate a reason for monitoring. For more information on developmental milestones see below the link under "what professionals.

What parents may identify[edit | edit source]

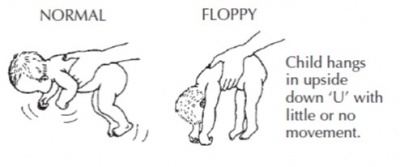

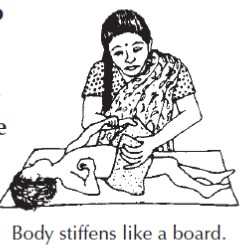

The primary indicators parents will notice are developmental delay and impaired muscle tone. Developmental delays occur when a child does not develop specific skills within the predicted time period. If parents are worried about the development of their child, it is important to take them seriously. Young babies may show some of these signs:

- Stiffness

- Floppiness

- Slow development

- Poor feeding

- Unusual behaviour

What Professionals may Observe[edit | edit source]

Professionals should use the input of the parents as basis for further examinations (history or assessment).In the case of cerebral palsy, developmental motor delay is a key indicator. The professional should evaluate:

- Muscle tone

- Movement coordination and control

- Reflex irregularity

- Posture

- Balance

- Fine motor function

- Gross motor function

- Oromotor function

To find out more about normal development see this page.

Medical History[edit | edit source]

Doctors will want to know about the child’s prenatal history, as well as any complications during pregnancy, labour and delivery. If the child’s condition is showing signs of progression, these signs will help doctors rule out a cerebral palsy diagnosis. As with many aspects of diagnosing cerebral palsy, this requires observation over time. Eliminating other differential diagnoses is a crucial factor in diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Both parents’ medical histories are important to this process. By reviewing medical history of parents, doctors can look for possible genetic, progressive or degenerative nervous system disorders.

Medical Examination[edit | edit source]

Common tests by neurologists or neuroradiologists may include neuroimaging such as cranial ultrasound, computed tomography scan (CT Scan) and magnetic resonance imaging scans (MRIs). These tests will allow neurologists to actually “see” the brain. Various disorders, injuries and conditions yield different results. These can be used to rule out cerebral palsy or, if cerebral palsy is eventually diagnosed, they can provide doctors with an exact picture of the injury to the brain. Seizure activity will also be monitored if present.

Other specialists can be brought in to test hearing, vision and perception, as well as cognitive, behavioural and physical development. A child may be sent to an orthopaedic surgeon to ascertain delay in motor development, record persistence of primitive reflexes, examine for dislocated hips and check on abnormal postural reactions.

Reflexes are something which are examined by medical professionals. In the newborn, they are known as primitive reflex movements. These are complex, stereotypical patterns that occur in response to a variety of sensory stimuli. At birth almost all motor behaviour is controlled by these primitive reflexes. Within a few months, they are replaced by a more mature set of protective and postural reflexes called advanced postural reactions that position the body segments against each other and gravity. Advanced postural reactions provide the basis for trunk balance and voluntary control of movements. The child gains motor skills as primitive reflexes are suppressed and advanced postural reactions are established. have a look at this page on normal development for more information on primitive reflexes. If primitive reflexes persists past a 6 months, it can be a sign of pathology. Some reflexes are important to recognise because they will affect the functioning of the child.

For example:

The reflexes triggered by the position of the head. That is why good positioning of the body is so important. The persistence of the sucking reflex (or biting reflex) will affect how to feed a child.

It is important to recognise reflexes for this purpose but primarily it is much more useful to be able to classify the gross motor, the fine motor and the communication because these are much more important for planning interventions.

Reactions of Parents to the Diagnosis of CP[edit | edit source]

It can take months or even years to confirm the diagnosis of CP. The impact of getting this diagnosis can be difficult and emotional for the parents. Parents may initially shy away from the news, especially if they were fostering hope that their child would 'outgrow' the condition. The diagnosis may bring a mixture of fear, guilt, or apprehension. Some parents may wonder if the cause of the child’s impairment is somehow their fault or whether they did something wrong. Others may be relieved that their child has a physical impairment but is expected to live a full, long life.

Professionals may not want to deliver the diagnosis of CP until they are fully certain. They do not want to misdiagnose and cause undue stress. They may delay to deliver the diagnosis because they are afraid it will interfere with the bonding between the parents and the child. Sometimes professionals just do not know how to give 'bad news' to people.

Tips on Talking about the Diagnosis to Parents[edit | edit source]

As a Physiotherapist you may not be the one delivering the diagnosis but it is important to consider possible consequences of your way of delivering information to the parents. It is important to give them the truth; take time, but be sure to discuss it again at subsequent visits with the family. The family will need time to think, discuss and ask questions. At the same time, early interventions should start immediately (intervention are more effective if started early) which can give the parents a feeling that they can do something. If providing only half of the message and/or giving (unrealistic) hopes, parents will expect too much, will get disappointed easily with the results of the interventions (and also in you as the professional) and may start to 'shop around' for a cure.

Parents may seek a second opinion to confirm the diagnosis of cerebral palsy and to rule out the possibility of misdiagnosis. Among the parents going to another doctor there are many who do this because nobody took time to explain properly what cerebral palsy is, what could be the cause, what can be done and who can help them. Alternatively, they do not believe that nothing can be done to cure the child. There are many parents who visit several doctors, often far away in the city because there is no specialist in their own area and they want the best future for their child. A good and repeated explanation to the parents and referring the family for further support (preferably a community-based rehabilitation programme in their own area) could save a lot of money, time and false hope of families.