Dyspareunia

Definition[edit | edit source]

Dyspareunia is defined as persistent genital pain that occurs during sexual intercourse.[1] Its often associated with sexual function problems such as; Vaginal dryness, anxiety during sexual intercourse, Difficultly in reaching climax and so on.[2] It can be classified into two types based on the location of the pain – entry or deep dyspareunia. While entry dyspareunia is associated with pain upon an attempt at vaginal penetration at the introitus, deep dyspareunia is pain perceived upon vaginal penetration and causes include adenomyosis, endometriosis, vaginal scarring, interstitial cystitis, and pelvic adhesions. [3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of dyspareunia varies from 8% to 21.1% globally, as reported by the World Health Organization in 2006. [4]

A recent systematic review concluded the prevalence of dyspareunia as 42% at 2 months, 43% at 2–6 months, and 22% at 6–12 months postpartum. Given these high prevalence as well as the impact on a woman's life, the study highlighted the need for special attention to dyspareunia during the postpartum period. [5]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

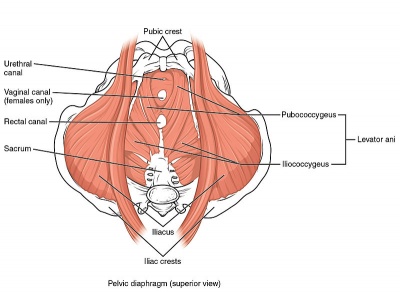

Weakness in deep pelvic floor muscles (levator ani muscle group and coccygeus) can cause deep dyspareunia. [6][7][8]

The pudendal nerve (composed of somatic branches from the sacral plexus, specifically S2 to S4 [9] [10] [11][12]) is one of the most important nerves associated with dyspareunia or pelvic pain. Due to its location in the pelvis, it is susceptible to injury during pelvic surgeries and parturition. [9][11]

Entry dyspareunia usually involves the vulva and its surrounding structures [8]

Deep dyspareunia is characterized by pain experienced during deep vaginal penetration and might involve the inner pelvic structures such as the urinary bladder and cervix. [8][7]

Please see the page "Pelvic Floor Anatomy" for further details regarding anatomy.

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Dyspareunia could be a symptom stemming from one or more of the following:

- Skin irritation (i.e. eczema or other skin problems in the genital region)[1]

- Endometriosis[13]

- Vestibulodynia

- Vulvodynia[14]

- Vaginismus[13]

- Interstitial cystitis[14]

- Fibromyalgia[14]

- Irritable bowel syndrome[14]

- Pelvic inflammatory disease[15]

- Depression and/or anxiety[15]

- Post-menopause[15]

- Postpartum dyspareunia [3]

- Inadequate vaginal lubrication or arousal [3]

- Anogenital causes such as haemorrhoids and anal fissures [3]

- Bartholin gland infection [3]

- Vulvovaginitis [3]

- Vaginal atrophy [3]

- Adenomyosis [3]

- Vaginal scarring [3]

- Pelvic adhesions [3]

- Urinary tract infection(UTI)[16]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Individuals may present with pain that occurs at entry during penetration, with deep penetration or pain post-penetration. The patient may also describe pain associated with the insertion of a tampon or during a Pap exam.

Words used to describe pain may be (but are not limited to): "throbbing" "burning" or "aching." [17]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

History Taking[edit | edit source]

A recent study [3] summarised important findings related to the history taking:

- Accurate clinical diagnosis requires detailed information about the location, onset, duration, severity, nature of pain, precipitating factors, and positions associated with the pain. [8][7]

- It is particularly helpful to know the specific location of the pain, especially if it is localized to the vulva, vagina introitus, or inside of the vagina, as this can help narrow down the possible causes.

- In his article on the clinical approach to dyspareunia, Graziottin provides a comprehensive guide to the necessary questions for a thorough history and physical examination. [18]

Another study [4] listed the important elements to discuss during clinical evaluation of female sexual pain as below:

- Pain characteristics: Timing, duration, quality, location, provoked, or unprovoked

- Musculoskeletal history: Pelvic floor surgery, trauma, obstetrics

- Bowel and bladder history: Constipation, diarrhoea, urgency, frequency

- Sexual history: Frequency, desire, arousal, satisfaction, relationship

- Psychological history: Mood disorder, anxiety, depression

- History of abuse: Sexual, physical, neglect.

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

The gold standard to assess the pelvic floor muscles is through an internal exam, performed by a trained medical professional with the informed consent of the patient. This exam allows for the assessment of the health of the tissue, the tonicity of the pelvic floor muscles, the ability to contract and relax these muscles and to assessment of vulvodynia and/or vestibulodynia.

Before starting the physical examination, since the patient may have anxiety about genital examinations, it can be helpful to explain to the patient why it is essential and how it may be useful for the diagnosis and the treatment. [19] The physical examination may include the following elements:

- Inspection: Includes visual examination of the external genitals for atrophy, discolouration, erythema, lesions, or trauma. [20]

- Palpation: Includes systemically pressing on the external genital tissue (including the hymen) with the use of a small cotton to localize the pain for patients reported focal pain; performing single-digit examination with a lubricated single finger to detect any narrow introitus / pain with palpation of the pelvic floor / pelvic floor muscle tension or pain / uterine prolapse or retroversion (may cause pain when the uterus is gently moved cephalad) / tenderness with uterine manipulation / bladder base tenderness / pelvic masses; and rectovaginal examination especially for those with rectal pain or dyschezia to check any rectovaginal or uterosacral nodularity that is palpable during the test. [20]

Additional Testing[edit | edit source]

Additional tests that can be useful in the diagnostic process are listed according to the causes of the dyspareunia:

- Vaginitis: Speculum examination [20], pH testing, microscopy, polymerase chain reaction swab as indicated

- Sexually transmitted infections: Cervical cytology testing [20]

- Interstitial cystitis: Interstitial cystitis questionnaire, bladder instillation, cystoscopy

- Ovarian masses: Transvaginal ultrasonography

- Uterine retroversion: Usually unnecessary but transvaginal ultrasonography can be used to exclude myomas

- Adhesions or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease: Pelvic imaging to exclude other diagnoses

- Endometriosis: Laparoscopy (unless the diagnosis is uncertain or patient desires)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

When quantifying the pain, validated self-report questionnaires such as the Female Sexual Function Index, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, or the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) vulvar discomfort scale may be more helpful instead of asking a patient to rate their pain on one to 10. [19]

The Female Sexual Destress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R): A single item from this scale may be a useful tool in quickly screening for sexual distress in middle-aged women.[21]

Outcome measures used in a randomised control study were:

- Modified Oxford Scale: A 0-5 grade scale to assess the strength and endurance of the pelvic floor muscles.

- Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A questionnaire including six parts that evaluate desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and painless intercourse. The total score ranges from 2 to 95.

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Multidisciplinary Approach[edit | edit source]

The use of a multidisciplinary approach with the inclusion of a gynaecologist, urologist, psychiatrist, pain management expert, physical therapist, sexual therapist, and mental health professionals with a specialization in chronic pain is advantageous to address all the aspects of pain (physical, emotional, and behavioural). [22]

The first step towards treating a patient's pain is for the physician to acknowledge that the patient is experiencing it. The physician should counsel the patient that pain management might take time and that it may not completely go away even after treatment. The patient should be informed about all the available treatment options and should be helped in selecting the best possible option. The initial step should be a conservative, nonsurgical approach. Treatment options depend on the aetiology of the patient's complaint and can include: [23]

- Oral tricyclic antidepressants

- Oral or topical hormonal replacement

- Oral NSAIDs, and botox injections: Botulinum toxin injection is effective in treating dyspareunia caused by pelvic floor myalgia and contracture. [24][25]

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy, and other brain-based therapies: Cognitive-behavioral therapy is the most commonly used behavioural intervention and is strongly recommended. It is an effective behavioural intervention in reducing anxiety and fear associated with dyspareunia. [26]

- Systemic and topical hormone replacement therapy, selective estrogen receptor modulator therapy, and the use of vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone: For the patients with dyspareunia due to post-menopausal vaginal atrophy. [27]

- Appropriate antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral therapy based upon culture results: For dyspareunia due to infectious causes.

- Vaginal lubricants, scar tissue massage: Post-partum dyspareunia can respond to these options.

- Pelvic floor rehabilitation: According to previous studies [28][29][30][31] [32][33][34] [35] it is an effective approach in the treatment of dyspareunia. Although most of the studies were retrospective or observational, a recent randomised control study [36] concluded that pelvic floor rehabilitation is an important part of a multidisciplinary treatment approach to dyspareunia. It can serve as an adjuvant treatment option in most cases of dyspareunia. It relaxes the pelvic floor muscles and re-educates the pain receptors. [37]

- Surgical treatment: Only adopted as a last option when all conservative treatment options have failed. It is usually useful in identifying and/or treating pelvic adhesions, endometriosis, and pelvic organ prolapse. [38]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

A pelvic floor rehabilitation led by a physiotherapist can include;

- Patient education: It plays an important role in the treatment of dyspareunia. [32][33] Instructing the patient about the anatomy and function of the pelvic floor muscles (PFM) and guiding the patient on how to self-control the activity of these muscles are very important parts of the treatment. In this way, the patient can relax and contract them when required. [36]

- Manual techniques: Since trigger and tender points have been reported to be one of the musculoskeletal sources of dyspareunia, manual techniques can play an important role in rehabilitation. As well as releasing the trigger and render points, they increase the awareness of the patient's PFM, normalize the overactivity, and increase the strength of the PFM. Among the techniques, myofascial release and intravaginal massage can be useful in improving vascularization, and releasing muscle trigger points in the pelvic floor and, thus, can be efficient in treating pain and sexual dysfunction. [36]

- Modalities: Electrotherapeutic modalities such as transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation (TENS) and functional electrical stimulation (FES), or heat and cold modalities can be used. [36]

- Pelvic floor muscle exercises: They can be implemented with or without biofeedback. Biofeedback is an important adjunct for the physiotherapist to instruct and educate the patient to find and feel their PFM, realize the normal activity of the PFM, and then later force/strengthen the pelvic floor if needed. [36]

Physiotherapists can address factors contributing to dyspareunia with the following tools and techniques.

| Contributing factor | Tool/Technique |

|---|---|

| Lack of awareness of pelvic floor muscles | Assess the patient's ability to connect with their pelvic floor muscles through their ability to correctly contract and relax their pelvic floor muscles. If the patient is unable to correctly recruit these muscles, whether it be due to lack of strength or neuromotor connection, this should be addressed. |

| Hypertonic pelvic floor muscles | Teaching relaxation techniques for the pelvic floor muscles:

The use of inserts can be beneficial along with these techniques. Teach the patient to move the dilator or insert past the entrance of the vaginal canal in conjunction with relaxing the pelvic floor muscles. |

| Pain centralization | If this has been a chronic issue, addressing the principles of centralized pain and explaining this to the patient can be helpful and informative. Additionally, pain at the entrance or through the vaginal canal can elicit a spasm or hypertonic response by the pelvic floor muscles. |

Additional Considerations[edit | edit source]

- The use of a multidisciplinary approach with the inclusion of a physician and a counselling therapist could be beneficial, depending on the reason for experiencing dyspareunia.

- Issues such as fatigue, depression/anxiety, stress or a history of abuse can contribute to the tension of the pelvic floor muscles, and this may be addressed through counselling.

- Ensure that the patient has been screened by a physician to rule out any differential diagnoses or address co-existing diagnoses that are out of the physiotherapy scope of practice.

Occupational Therapy[edit | edit source]

Occupational therapy can be applied by an occupational therapist as part of pelvic floor rehabilitation. [39][40]

It is an important part of the multidisciplinary approach since the pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms limiting effect on the patient's occupational performance, specifically sexual activity and exercise, after childbirth is proved. [41]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Dyspareunia may be a result of many factors as listed above. To elicit the cause, the combination of the patient's history and physical examination findings should be considered. [20]

A recent study [20] summarised some of the causes of dyspareunia with associated history and physical examination findings:

| Diagnosis | Historical clues | Examination findings |

|---|---|---|

| Dermatologic diseases | Burning, dryness, pruritus | Visible skin changes (dependent on condition) |

| Inadequate lubrication | Dryness; history of Diabetes Mellitus; history of chemotherapy or use of progestogens, aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists | Vulva may be normal or appear dry |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction | Difficulty evacuating stool or emptying the bladder; aching after intercourse; pain in lower back, thighs, or groin | Painful vaginal muscles just inside of the hymen during single-digit examination |

| Vaginal atrophy | Burning, dryness | Tissue may appear pale and dry (although may appear normal in early menopause) |

| Vaginismus | Difficulty achieving penetration; possible history of anxiety, sexual abuse or trauma, or other causes of painful penetration; sometimes no prior risk factors are present | Involuntary contraction of pelvic floor muscles with attempted insertion of finger or small speculum |

| Vaginitis | Discharge, burning, or odour | Vaginal discharge |

| Vulvodynia | Chronic burning, tearing, aching, or stabbing vulvar pain of at least three months duration | Vulva may be visually normal or may have focal areas of erythema around the vestibule and hymen that are painful, as elicited by a cotton swab |

| Interstitial cystitis | Urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia | Pain with palpation of bladder base |

| Ovarian masses | Lateralized pain with intercourse | Pain with adnexal palpation |

| Uterine retroversion | Pain may be related to sexual position; and may be associated with endometriosis | Retroverted uterus, may be painful when moved cephalad |

| Adhesions or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease | May have lateralized, sharp pain; history of pelvic inflammatory disease or pelvic surgery | Possible fixation of pelvic organs on bimanual examination |

| Endometriosis | Family history; dysmenorrhea common | Generalized pelvic tenderness; nodularity may be noted in cul-de-sac during rectovaginal examination |

Resources[edit | edit source]

- To read the recommended measurement tools prepared by the Pelvic Floor Disorders Consortium: "Measuring Pelvic Floor Disorder Symptoms Using Patient-Reported Instruments" [42]

- To watch the webinar by pelvic floor physiotherapist Janetta Webb from the Jean Hailes organisation: "Webinar: Dyspareunia - The physiotherapist's perspective" [43]

- This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mayo Clinic. Painful intercourse. Available from:https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/painful-intercourse/symptoms-causes/syc-20375967 (accessed 13 Feb 2019).

- ↑ Mitchell KR, Geary R, Graham CA, Datta J, Wellings K, Sonnenberg P, Field N, Nunns D, Bancroft J, Jones KG, Johnson AM. Painful sex (dyspareunia) in women: prevalence and associated factors in a British population probability survey. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017 Oct;124(11):1689-97.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 Alimi Y, Iwanaga JO, Oskouian RJ, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. The clinical anatomy of dyspareunia: A review. Clinical Anatomy. 2018 Oct;31(7):1013-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, Feranec J. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018 Mar 27;10(3).

- ↑ Banaei M, Kariman N, Ozgoli G, Nasiri M, Ghasemi V, Khiabani A, Dashti S, Mohamadkhani Shahri L. Prevalence of postpartum dyspareunia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2021 Apr;153(1):14-24.

- ↑ Edwards L. Vulvodynia. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Mar 1;58(1):143-52.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. American family physician. 2014 Oct 1;90(7):465-70.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Howard FM, editor. Pelvic pain: diagnosis and management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Prather H, Dugan S, Fitzgerald C, Hunt D. Review of anatomy, evaluation, and treatment of musculoskeletal pelvic floor pain in women. PM&R. 2009 Apr 1;1(4):346-58.

- ↑ Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy 41st Edition: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Woodman PJ, Graney DO. Anatomy and physiology of the female perineal body with relevance to obstetrical injury and repair. Clinical Anatomy: The Official Journal of the American Association of Clinical Anatomists and the British Association of Clinical Anatomists. 2002 Aug;15(5):321-34.

- ↑ Ventolini G. Vulvar pain: anatomic and recent pathophysiologic considerations. Clinical Anatomy. 2013 Jan;26(1):130-3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. When sex is painful. Available from:https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/When-Sex-Is-Painful (accessed 21 Feb 2019).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, Edwards RM, Chen D, Haefner HK. Relationship between vulvodynia and chronic comorbid pain conditions. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;120(1):145.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, et al. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:749. Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7544):749-55.

- ↑ Siedhoff MT, Carey ET, Findley AD, Hobbs KA, Moulder JK, Steege JF. Post-hysterectomy dyspareunia. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2014 Jul 1;21(4):567-75.

- ↑ Morris C, Briggs C, Navani M. Dyspareunia. InnovAiT. 2021 Oct;14(10):607-14.

- ↑ Graziottin A. Clinical approach to dyspareunia. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001 Oct 1;27(5):489-501.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, Bergeron S, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S. Vulvodynia: assessment and treatment. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016 Apr;13(4):572-90.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Hill DA, Taylor CA. Dyspareunia in women. American family physician. 2021 May 15;103(10):597-604.

- ↑ Carpenter JS, Reed SD, Guthrie KA, Larson JC, Newton KM, Lau RJ, Learman LA, Shifren JL. Using an FSDS‐R Item to Screen for Sexually Related Distress: A MsFLASH Analysis. Sexual medicine. 2015 Mar;3(1):7-13.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 673-Persistent vulvar pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):e78-84.

- ↑ Tayyeb M, Gupta V. Dyspareunia.

- ↑ Park AJ, Paraiso MF. Successful use of botulinum toxin type a in the treatment of refractory postoperative dyspareunia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009 Aug 1;114(2 Part 2):484-7.

- ↑ Pelletier F, Girardin M, Humbert P, Puyraveau M, Aubin F, Parratte B. Long‐term assessment of effectiveness and quality of life of OnabotulinumtoxinA injections in provoked vestibulodynia. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2016 Jan;30(1):106-11.

- ↑ Engman M, Wijma K, Wijma B. Long-term coital behaviour in women treated with cognitive behaviour therapy for superficial coital pain and vaginismus. Cognitive behaviour therapy. 2010 Sep 1;39(3):193-202.

- ↑ Naumova I, Castelo-Branco C. Current treatment options for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. International journal of women's health. 2018 Jul 31:387-95.

- ↑ Berghmans B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: an untapped resource. International urogynecology journal. 2018 May;29:631-8.

- ↑ Montenegro ML, Vasconcelos EC, Candido Dos Reis FJ, Nogueira AA, Poli‐Neto OB. Physical therapy in the management of women with chronic pelvic pain. International journal of clinical practice. 2008 Feb;62(2):263-9.

- ↑ Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S, Pagidas K, Glazer HI, Meana M, Amsel R. A randomized comparison of group cognitive–behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001 Apr 1;91(3):297-306.

- ↑ Rivalta M, Sighinolfi MC, Micali S, De Stefani S, Bianchi G. Sexual function and quality of life in women with urinary incontinence treated by a complete pelvic floor rehabilitation program (biofeedback, functional electrical stimulation, pelvic floor muscles exercises, and vaginal cones). The journal of sexual medicine. 2010 Mar;7(3):1200-8.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bø K, Kvarstein B, Hagen RR, Larsen S. Pelvic floor muscle exercise for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: II. Validity of vaginal pressure measurements of pelvic floor muscle strength and the necessity of supplementary methods for control of correct contraction. Neurourology and urodynamics. 1990;9(5):479-87.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Fisher KA. Management of dyspareunia and associated levator ani muscle overactivity. Physical therapy. 2007 Jul 1;87(7):935-41.

- ↑ Ensor AW, Newton RA. The role of biofeedback and soft tissue mobilization in the treatment of dyspareunia: a systematic review. J Womens Health Phys Ther. 2014;38(2):74–80.

- ↑ Morin M, Carroll MS, Bergeron S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of physical therapy modalities in women with provoked vestibulodynia. Sexual medicine reviews. 2017 Jul;5(3):295-322.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Ghaderi F, Bastani P, Hajebrahimi S, Jafarabadi MA, Berghmans B. Pelvic floor rehabilitation in the treatment of women with dyspareunia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. International urogynecology journal. 2019 Nov;30:1849-55.

- ↑ Rosenbaum TY. Physiotherapy treatment of sexual pain disorders. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2005 Jul 1;31(4):329-40.

- ↑ Kliethermes CJ, Shah M, Hoffstetter S, Gavard JA, Steele A. Effect of vestibulectomy for intractable vulvodynia. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2016 Nov 1;23(7):1152-7.

- ↑ Groetken P. Occupational Therapy's Role in Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation.

- ↑ Heine A. The Role of Occupational Therapy in the Physical and Psychological Rehabilitation of Perinatal Mothers.

- ↑ Burkhart R, Couchman K, Crowell K, Jeffries S, Monvillers S, Vilensky J. Pelvic floor dysfunction after childbirth: occupational impact and awareness of available treatment. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2021 Apr;41(2):108-15.

- ↑ Bordeianou LG, Anger J, Boutros M, Birnbaum E, Carmichael JC, Connell K, De EJ, Mellgren A, Staller K, Vogler SA, Weinstein MM. Measuring pelvic floor disorder symptoms using patient-reported instruments: proceedings of the consensus meeting of the pelvic floor consortium of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the International Continence Society, the American Urogynecologic Society, and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction. Techniques in coloproctology. 2020 Jan;24:5-22.

- ↑ Jean Hailes. Webinar: Dyspareunia - The physiotherapist's perspective. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rpIi_1SVTeg. 2016.

- ↑ Physiopedia. Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w08iCzxnQBU