Hallux Rigidus

Original Editor - Tracy Hall

Top Contributors - Admin, Ewa Jaraczewska, Rachael Lowe, Jess Bell, Tracy Hall, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Ilse De Bode, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Khloud Shreif

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Hallux rigidus is an degenerative osteoarthritic condition of the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ-1).[1] It is characterised by a complete absence of the joint's sagittal plane motion, specifically dorsiflexion, at the end stages of the disease.[2] Hallux limitus (HL) is the name given to the earlier stage of this condition when there is restriction in the sagittal plane of motion.[3] This article will discuss multiple conservative management concepts and the main operative procedures used to treat hallux rigidus.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Structure[edit | edit source]

The first metatarsophalangeal joint consists of several anatomic structures which, during athletic activities, support a weight up to eight times heavier than the body.[4]

Osseous components:

- The first metatarsal head has two grooves on its plantar surface, and it accommodates the articular surfaces of the medial and lateral sesamoid bones. Cartilage lesions mostly appear on the dorsal aspect of the first metatarsal head.[5]

- The proximal phalanx serves as an attachment site for muscles and ligaments.

- The medial (tibial) and lateral (fibular) sesamoid bones are located on the plantar surface of the first metatarsal head.

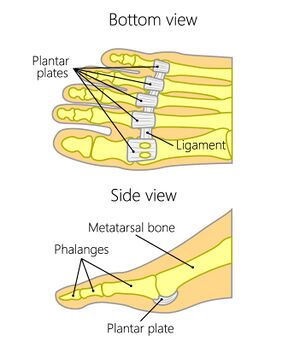

Plantar plate complex of the great toe:

This fibrocartilaginous pad forms a functional unit with the plantar capsule, intersesamoid ligament, paired metatarsosesamoid ligaments, sesamoid phalangeal ligaments, and musculotendinous structures of the first MPJ. Its role includes:

- dispersing body weight to the sesamoids

- protecting the articular surfaces

- allowing gliding of the metatarsal head along the joint capsule and at the smaller sesamoid articulations

- assisting propulsion during gait and sports activities

- allowing effective acceleration and maintaining optimal body balance

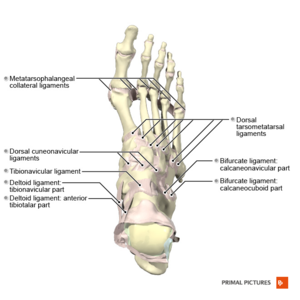

Collateral ligaments:

The medial and lateral metatarsophalangeal ligaments (collateral ligaments) originate from the metatarsal condyle tubercle and insert into the tubercle at the base of the proximal phalanx. Despite not belonging to the plantar plate complex, they provide static stabilisation when valgus or varus forces are applied to the joint.

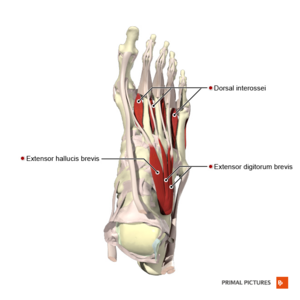

Dorsal extensor tendons:

The extensor hallucis longus (EHL) and extensor hallucis brevis (EHB) tendons provide dynamic stability during plantar flexion.

Sagittal bands:

These ligaments encircle the metatarsophalangeal joint. They are adjacent to the joint capsule and extend from the tendons to the sesamoids. They stabilise and centralise the extensor tendons during motion.

Range of Motion[edit | edit source]

- The normal resting position of the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint relative to the longitudinal axis of the 1st metatarsal is 16 degrees of dorsiflexion.[3]

- Range of motion: passive plantarflexion is 3-43 degrees, and passive dorsiflexion is between 40 and 100 degrees.

- A normal gait cycle requires 45-60 degrees of 1st metatarsophalangeal extension.

Function of the Hallux[edit | edit source]

The hallux is critical for daily functioning and activity:[3]

- During the stance phase of gait, the hallux bears twice the load of the other toes and approximately 40-60% of the body weight.

- During dynamic activity, the great toe aids in the natural movement of the foot, allowing the body to move forward in space. During stance phase, body weight and ground reaction forces tend to flatten the medial longitudinal arch, and the Windlass mechanism counteracts this.[7] Read about the Windlass mechanism here.

- The great toe plays an important role in static and dynamic balance. Single-leg stance performance and directional control ability during forward/backward weight shifting can be impaired if the great toe is constrained.[8]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

The majority of hallux rigidus cases are idiopathic. Traumatic or iatrogenic injuries can damage the articular cartilage of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint and lead to the development of hallux rigidus. Additionally, the presence of the following structural changes may correlate with the development of hallux limitus and hallux rigidus:

- Dorsiflexed first metatarsal relative to the second metatarsal[9]

- Plantar flexed forefoot on the rear foot[9]

- Reduced first metatarsophalangeal joint range of motion[9]

- Longer proximal phalanx, distal phalanx, medial sesamoid, and lateral sesamoid[9]

- Wider first metatarsal and proximal phalanx[9]

- Coughlin and Shurnas[10] also reported an association between hallux rigidus and a flat or chevron-shaped metatarsophalangeal joint, metatarsus adductus, and hallux valgus interphalangeus

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- According to a study conducted by Senga et al.,[11] knee osteoarthritis, hallux valgus and episodes of gout were independent risk factors for hallux rigidus

- A family history of hallux rigidus is consistent with bilateral hallux rigidus[10]

- Unilateral hallux rigidus can occur in patients with a history of trauma[10]

- There is a higher prevalence of hallux rigidus in older adults (≥50 years)[11]

- There is a greater frequency of hallux rigidus in females[12][13]

- An individual's height impacts hallux rigidus: "the greater the height of the patient, the greater the development of hallux rigidus"[12]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Individuals with hallux rigidus present with various signs and symptoms, including:

- pain (burning pain and paraesthesia might be present)

- swelling and redness of the joint[3]

- stiffness

- loss of motion (a total absence of movement)[5]

- reduced plantarflexion range at the ankle joint[14]

- plantar calluses[11]

- joint enlargement[11]

The following functional limitations can be present:

- increased pain with walking, running or squatting

- antalgic gait pattern:[3]

- decreased toe-off

- shortened stride or step length

- compensatory adaptations include:

- external rotation of the ipsilateral hip

- hip hiking and circumduction allow the toe of the involved limb to clear the floor during the swing phase of gait

- increase in lateral forefoot loading[14] [15](uneven shoe wear with evidence of increased wear under the MPJ-2 and lateral forefoot)

- less total ankle joint excursion during level walking[14]

- increased forefoot supination during push-off[16]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Radiograph[edit | edit source]

Weight-bearing, anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs are usually needed to examine the joint.[17] Often, non-uniform joint space narrowing, and widening or flattening of the 1st metatarsal head are seen. Subchondral sclerosis or cysts, horseshoe-shaped dorsal osteophytes, and osteophytes on the edges of the joints may be seen.[1] In addition, sesamoid hypertrophy may be present.

Classification Systems for Hallux Rigidus[edit | edit source]

Regnauld Classification[18][edit | edit source]

A clinical/radiographic grading system described by Regnauld appears mainly in the European literature:

- Grade I: functional hallux limitus

- Grade II: joint adaptation with flattening of the first metatarsal head and pain at the end range of motion

- Grade III: arthrosis with severe flattening of the first metatarsal head, osteophytes, asymmetric joint space narrowing, and erosions

Hattrup and Johnson Classification[19][18][edit | edit source]

- Grade I: mild to moderate formation of osteophytes with no joint space involvement

- Grade II: moderate osteophyte formation, joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis

- Grade III: increased osteophyte formation and loss of joint space

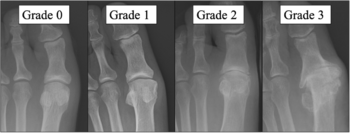

Coughlin and Shurnass Classification[edit | edit source]

Coughlin et al.[20] modified the Hattrup and Johnson classification to create the Coughlin and Shurnass[10] classification:

- Grade 0: Dorsiflexion 40-60°, normal radiography, pain not present

- Grade 1: Dorsiflexion 30-40°, dorsal osteophytes, minimal/ no other joint changes

- Grade 2:Dorsiflexion 10-30°, mild to moderate joint narrowing or sclerosis, osteophytes

- Grade 3: Dorsiflexion less than 10°, severe radiographic changes, constant moderate to severe pain at extremities

- Grade 4: Stiff joint, severe changes with loose bodies and osteochondritis dissecans

Roukis Classification[18][edit | edit source]

- Grade 1: Metatarsus primus elevates, periarticular subchondral sclerosis, minimal dorsal exostosis and minimal flattening of the metatarsal head

- Grade 2: Moderate dorsal exostosis, flattening metatarsal head, minimal joint space narrowing, sesamoid hypertrophy

- Grade 3: Severe dorsal exostosis, focal joint space narrowing, cyst formation, loose bodies

- Grade 4: Excessive exostosis of the metatarsal head and proximal phalanx base, absent joint space, ankylosis

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical examination of the patient with hallux rigidus should include the following:

- Observation: osteophytes can be visualised and palpated, and foot shape and the alignment of the great toe can be altered. Malalignment of the great toe includes hyperextension of the first interphalangeal (IP) joint, and the big toe turning towards the adjacent toe. The foot shape may be affected by swelling, callus formation on the sole of the foot and increased weight bearing on the lateral aspect of the foot.

- Palpation: tenderness can be present at the dorsal joint. Extreme dorsiflexion may produce pain due to an impingement of the dorsal osteophytes. Additionally, traction of extensor hallucis longus (EHL) over dorsal osteophytes during plantar flexion can cause pain.

- First MTP joint compression: positive "grind testing" indicates more advanced arthritis. Pain in the mid range of motion may also indicate the progression of arthritis. Patients may demonstrate hyperextension of the first interphalangeal (IP) joint as a reaction to limited first MTP dorsiflexion.[21]

- Range of motion assessment: ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion range of motion. In advanced arthritis, patients report pain in mid-range. The degree of rigidity can be defined by the pain present during dorsiflexion, plantarflexion or throughout the range of movement.

1st MTP joint extension test:

- Passive testing: Patient is in a standing position, with their knee flexed: passively lift their big toe. Measure toe extension. Return to starting position. Then, manually laterally rotate the tibia through the calf muscles. This allows the subtalar joint to supinate and increases the height of the medial longitudinal arch. Passively lift the big toe. Measure toe extension. The difference between the two measures may be because tension on the plantar fascia is decreased, allowing the big toe to extend further.

- Active testing: Patient is in a standing position. Stabilise the phalange on the ground and bring the same knee into flexion and ankle into plantarflexion. This results in the extension of the MTP joint.[14]

Non-Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Pharmacology[edit | edit source]

- Treatment for mild or moderate cases of hallux rigidus often includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) - these usually relieve some symptoms

- Cortisone injections give relief within 24 hours but often are only temporary (last for up to three months)[22][23]

- Intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate results in a "decrease in pain and improvement of function three months after the injection."[24][25]

Footwear, Insoles and Orthotics[edit | edit source]

Goal: to block or shield the hallux from dorsiflexion at the first metatarsal.

The following footwear modifications are grade C recommendations:

- Stiff inserts with a rigid bar or rocker bottom shoes. Rocker-bottom soles may be appropriate to off-load the extension moment of the MPJ-1 during toe-off[3]

- Stiff sole footwear or graphite inserts can help to decrease the extension moment at the MPJ-1[3]

- Wear shoes with a large toe box and stop wearing high heels [26]

Manual Techniques[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- To keep the talocrural joint mobile to preserve function

- To decrease pain with compression

- To preserve and increase MPJ-1 plantarflexion and dorsiflexion

The following techniques are recommended (Grade C evidence)

- 1st MTP distraction either alone or with dorsal and plantar glides[3]

- Grade III joint mobilisations on the medial and lateral sesamoids of the affected first MPJ[29][30]

Stretching and Strengthening[edit | edit source]

Goal: to improve the stability of the 1st MTP

- Isometric contractions of the flexor hallucis longus muscles with a 10-second hold[29]

- Isotonic strengthening of the flexor hallucis longus with manual resistance or resistive bands[29][3]

- Strengthening of the plantar intrinsic muscles[3]

- Stretching of the gastrocnemius and soleus[3]

- Star excursion-type exercises[3]

- Single-leg stance exercises - progress from standing on a hard surface to standing on the rocker board or BOSU[3]

Conditioning[edit | edit source]

Goal: to improve endurance

- Recumbent cycling[3]

- Aquatic therapy[3]

- Standing in chest-deep water to unweight the feet

- Hydrostatic pressure helps blood return to the heart

Activity Modification[edit | edit source]

Runners with stage II or more hallux rigidus may need to:[3]

- switch to lightweight day hikes

- switch from asphalt to dirt trails for long-distance running.

Surgical therapy[edit | edit source]

The indication for surgery is intractable pain isolated to the first metatarsophalangeal joint which does not improve with shoe modification, rigid shoe inserts, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and modification of activities. The choice depends on the stage of involvement, the limitations in range of motion, the activity level of the patient and the preferences of the surgeon and patient.

Types of surgery include:

- Cheilectomy. Treatment for early stages of hallux rigidus includes resection of < 30% of the dorsal metatarsal head and removal of bone spurs at the top of the joint. Usually beneficial for mild to moderate disease with less than 50% of joint affected, usually grade 1 and grade 2.[32][19][33][34][25]

- Dorsiflexion phalangeal osteotomy (Moberg osteotomy). In patients with a reasonable range of motion, a dorsal wedge osteotomy of the phalanx increases dorsiflexion at a theoretical cost of a loss of plantar flexion. It is typically performed in conjunction with a cheilectomy.[22] Mild to moderate cases occasionally require this procedure.

- Excision Arthroplasty or Keller procedure.[32][35] In the Keller procedure, the base of the proximal phalanx is resected and soft-tissue reconstruction is performed to decompress the joint and improve pain and range of movement. The Keller procedure may lead to great toe weakness, cock-up deformity and metatarsalgia.[36]

- MTP Arthrodesis. This is a procedure performed to fuse the joint surfaces.[37] It is a gold standard surgery for end-stage hallux rigidus,[3] [34] and is recommended when other procedures have failed (for example, the Keller procedure). Arthrodesis of the first MPJ consistently shows superior results and patient satisfaction compared to other surgical options. While cheilectomy may benefit the early stages of hallux rigidus, arthrodesis of the first MPJ appears to be the best option for relieving symptoms with stage III and IV hallux rigidus in active, athletic patients.[38]

- Artificial joint replacement. A procedure to replace joint surfaces with a plastic or metal surface. This technique of soft-tissue interposition arthroplasty gives excellent pain relief and reliable hallux function and is an alternative treatment to MTP arthrodesis in select cases of severe hallux rigidus.[39] The downside is that the joint may not last a lifetime, and there is currently no study documenting the long-term performance of any first MTP joint prosthesis in running athletes.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Turf toe, fracture, gout, rheumatoid arthritis could be some other causes of pain and stiffness in the 1st MTP joint.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Richie D. How To Treat Hallux Rigidus In Runners. 4 April 2009. Available from: https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/podiatry/how-to-treat-hallux-rigidus-in-runners

Foot and Ankle Center of Washington, Seattle. Available at https://www.footankle.com/hallux-rigidus/

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Patel J, Swords M. Hallux Rigidus. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556019/

- ↑ Massimi S, Caravelli S, Fuiano M, Pungetti C, Mosca M, Zaffagnini S. Management of high-grade hallux rigidus: a narrative literature review. Musculoskeletal Surgery. 2020 Dec;104:237-43.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 Finch R. Hallux Rigidus. Plus Course 2023

- ↑ Hallinan JTPD, Statum SM, Huang BK, Bezerra HG, Garcia DAL, Bydder GM, Chung CB. High-Resolution MRI of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint: Gross Anatomy and Injury Characterization. Radiographics. 2020 Jul-Aug;40(4):1107-1124.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Colò G, Fusini F, Zoccola K, Rava A, Samaila EM, Magnan B. May footwear be a predisposing factor for the development of hallux rigidus? A review of recent findings. Acta Biomed. 2021 Jul 26;92(S3):e2021010.

- ↑ SLO Motion Shoes. Hallux Rigidus: Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umCSpwEvWUM [last accessed 06/01/17]

- ↑ Williams LR, Ridge ST, Johnson AW, Arch ES, Bruening DA. The influence of the windlass mechanism on kinematic and kinetic foot joint coupling. J Foot Ankle Res. 2022 Feb 16;15(1):16.

- ↑ Chou SW, Cheng HY, Chen JH, Ju YY, Lin YC, Wong MK. The role of the great toe in balance performance. J Orthop Res. 2009 Apr;27(4):549-54.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Zammit GV, Menz HB, Munteanu SE. Structural factors associated with hallux limitus/rigidus: a systematic review of case-control studies. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Oct;39(10):733-42.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PS. Hallux rigidus: demographics, aetiology, and radiographic assessment. Foot & ankle international. 2003 Oct;24(10):731-43.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Senga Y, Nishimura A, Ito N, Kitaura Y, Sudo A. Prevalence of and risk factors for hallux rigidus: a cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021 Sep 13;22(1):786.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Rubio-Lorenzo M, Prieto-Montaña JR. Epidemiological factors of hallux rigidus. Orthopaedic Proceedings 2018; 91-B, No. SUPP_II. Available from https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/abs/10.1302/0301-620X.91BSUPP_II.0910324c [last access 04.02.2023]

- ↑ Beeson P, Phillips C, Corr S, Ribbans WJ. Hallux rigidus: a cross-sectional study to evaluate clinical parameters. Foot (Edinb). 2009 Jun;19(2):80-92.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Allan JJ, McClelland JA, Munteanu SE, Buldt AK, Landorf KB, Roddy E, Auhl M, Menz HB. First metatarsophalangeal joint range of motion is associated with lower limb kinematics in individuals with first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020 Jun 8;13(1):33.

- ↑ Miana A, Paola M, Duarte M, Nery C, Freitas M. Gait and Balance Biomechanical Characteristics of Patients With Grades III and IV Hallux Rigidus. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022 May-Jun;61(3):452-455.

- ↑ Stevens J, de Bot RTAL, Hermus JPS, Schotanus MGM, Meijer K, Witlox AM. Gait analysis of foot compensation in symptomatic Hallux Rigidus patients. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022 Dec;28(8):1272-1278.

- ↑ Arrondo G, Casola L. Hallux rigidus clinical examination, radiology, and classification. J Foot Ankle. 2021;15(3):198-200.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Dillard S, Schilero C, Chiang S, Pham P. Intra- and Interobserver Reliability of Three Classification Systems for Hallux Rigidus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2018 Apr 18:10.7547/16-126.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hattrup SJ, Johnson KA. Subjective results of hallux rigidus following treatment with cheilectomy. Clin Orthop 1988;226:182-91

- ↑ Coughlin MJ et al. Hallux rigidus. JBJS 2003; 85A:2072-88

- ↑ Bryant Ho B, Baumhauer J. Hallux rigidus. EFORT Open Reviews 2017; 2(1): 13-20

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lam A, Chan JJ, Surace MF, Vulcano E. Hallux rigidus: How do I approach it? World J Orthop. 2017 May 18;8(5):364-371.

- ↑ Grice J, Marsland D, Smith G, Calder J. Efficacy of Foot and Ankle Corticosteroid Injections. Foot Ankle Int. 2017 Jan;38(1):8-13.

- ↑ Pons M, Alvarez F, Solana J, Viladot R, Varela L. Sodium hyaluronate in treating hallux rigidus. A single-blind, randomized study. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 Jan;28(1):38-42.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Herrera-Pérez M, Pais-Brito JL, Valderrabano V, Cortés-García P, Déniz-Rodríguez B, Ayala-Rodrigo A. Propuesta de algoritmo terapéutico para hallux rigidus [Treatment algorithm proposed for hallux rigidus]. Acta Ortop Mex. 2014 Jul-Aug;28(4):253-7. Spanish.

- ↑ Ho B, Baumhauer J. Hallux rigidus. EFORT Open Rev. 2017 Mar 13;2(1):13-20.

- ↑ Gait Doctor NZ. 3 - Hallux Rigidus. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5tR7VSjgUEs [last accessed 5/2/2023]

- ↑ Ortho Eval Pal with Paul Marquis PT. Big Toe Pain "FIX" with Carbon Plate. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3mbI9qMEW6o [last accessed 5/2/2023]

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Shamus J, Shamus E, Gugel RN, Brucker BS, Skaruppa C. The effect of sesamoid mobilization, flexor hallucis strengthening, and gait training on reducing pain and restoring function in individuals with hallux limitus: a clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Jul;34(7):368-76.

- ↑ Kon Kam King C, Loh Sy J, Zheng Q, Mehta KV. Comprehensive Review of Non-Operative Management of Hallux Rigidus. Cureus. 2017 Jan 20;9(1):e987.

- ↑ Joan Hope Craig. Functional hallux mobilization. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZOur5I0RTVo [last accessed 5/2/2023]

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Mann RA, Clanton TO. Hallux rigidus: treatment by cheilectomy. J Bone Jt Surg 1988; 70A:400-6

- ↑ Gould N. Foot and Ankle.1981 May; 1(6):315-20.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PS. Hallux rigidus. Grading and long-term results of operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003 Nov;85(11):2072-88.

- ↑ Keller's arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg 1990; 72B:839-42

- ↑ Blewett N, Greiss ME. Long-term outcomes following Keller’s excision arthroplasty of the great toe. Foot 1993; 3:144-7

- ↑ Brodsky JW, Baum BS, Pollo FE, Mehta H. Prospective gait analysis in patients with first metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis for hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle International. 2007 Feb;28(2):162-5

- ↑ O'Doherty DP, Lowrie IG, Magnussen PA, Gregg PJ. The management of the painful first metatarsophalangeal joint in the older patient. Arthrodesis or Keller's arthroplasty? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990 Sep;72(5):839-42.

- ↑ Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PJ. Soft-tissue arthroplasty for hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle International. 2003 Sep;24(9):661-72.