Physical Activity in Individuals with Disabilities

Original Editor- Clara Hildt

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Tarina van der Stockt, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Mariam Hashem, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, Aminat Abolade, Merinda Rodseth, 127.0.0.1, Giulia Neculaes, Admin, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, Michelle Lee and WikiSysop

Introduction[edit | edit source]

There are 1.2 billion persons with disabilities in the world. They represent 15% of the global population and 80% of persons with disabilities reside in low-income countries.[1] In the United States, 20% of the population have a disability, which is 56 million adults. [2] In Australia 1 in 6 people have a disability. Profound or severe disability, meaning the person is unable to perform activities of daily living without assistance, affects 1 in 3 people. [3] The World Bank estimates that one-fifth of the world's population experiences significant disability.[4] The publication in the 2016 African Disability Rights yearbook reported that in Africa, female infants affected by disability were more likely to be killed at birth.[1]

There are numerous disabilities that can impact an individual's mobility, eyesight, hearing, cognition, memory, learning abilities, communication skills, mental well-being, and social interactions.[5]

Disability and Health[edit | edit source]

Sedentary behaviour, which is often associated with disability, leads to deconditioning and health risk. The problem is so specific that is described as Disability-Associated Low Energy Expenditure Deconditioning Syndrome.[6]

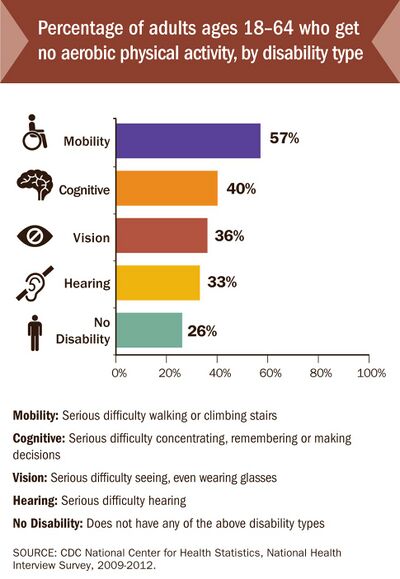

Individuals with disabilities are 57% more likely to be obese than adults without disabilities.[7] Obesity is an important risk factor for adults with disability with a 33% higher chance of having a chronic condition, such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke or cancer. [8]

The impact of these chronic diseases can be reduced by aerobic physical activity, but adults with disabilities only do physical activity on a regular basis about half as often as adults without disabilities (12% compared to 22%). [7][9]

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Definition[edit | edit source]

Physical Activity (PA) is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.[10] Activities undertaken while working, playing, travelling, carrying out housework and engaging in recreational pursuits are, therefore, included. The WHO recommends that adults do at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week or at least 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week.[11] However, about 25% of the world's population remain insufficiently active, and this number is twice as high in high-income countries.[11] Compared to those who meet activity criteria, people who are insufficiently physically active have a 20% to 30% increased risk of all-cause mortality.[12]

Methods of Measuring Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

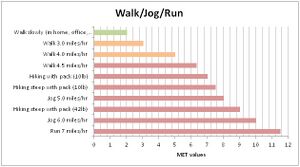

The level of physical activity can be measured in Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET), which is defined as a multiple of the resting metabolic rate. When considering individual characteristics, the threshold for the activity is based on relative intensities. Without taking a person's abilities into consideration, the absolute intensities become the reference threshold.[14] A MET score of 1 defines the level of energy used by the person when resting. When physical activity guidelines use absolute intensities as a reference point, light activity is considered when METs are less than 3, while METs from 3.0 to 5.9 are considered moderate activity. When MET is over 6, the activity is considered vigorous.

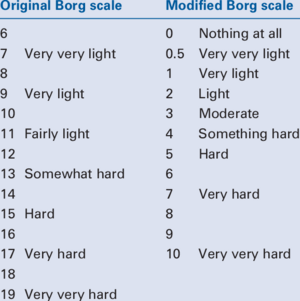

Another tool for measuring the level of physical activity is the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). It is based on a subjective, 6 to 20 scale and offers a good estimate of the heart rate during an activity.

Additional methods of measuring physical activities are:[15]

- Self-report questionnaires

- Self-report activities logs

- Direct observation

- Devices: accelerometers, pedometers, heart rate monitors, arm-band technology

Individuals with Disability[edit | edit source]

It is crucial to remember that a disability does not determine a person's identity. When interacting or collaborating with individuals who have disabilities, it is of utmost importance to prioritize the person over their disability. Utilizing positive language not only empowers them but also promotes inclusivity, making it imperative to always use inclusive language.[16][17]

"A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions)."[18]

In the medical model of disability, the condition is viewed as a medical and biological difficulty. Correcting ill-being is highlighted instead of preventing ill-being and promoting well-being. On the contrary, in the social model, disability is viewed as a difference and not judged. This model would emphasise barriers such as structural factors or discriminatory behaviours that prevent physical activity. Both the medical and social models are criticised for highlighting extreme points of view.[19] This led to the development of the social-relational model, which suggests that both impairments, as well as social and environmental barriers, can all operate simultaneously.[20]

Benefits of Physical Activity for Individuals with Disability[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is essential for quality of life and as a public health promoter. [19]

In people with disabilities, PA has an amplified importance based on higher rates of chronic diseases that PA can influence. Above those metabolic advantages, individuals with disabilities can further profit from PA:

- Health benefits:

- PA has amplified importance for cognitive, emotional and social difficulties.

- Psychological benefits such as enhanced self-perception through successful PA experiences.

- PA can reduce stress, pain, and depression. Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are commonly regarded as less challenging.

- Social contact:

- PA can reduce the stigmatisation process and negative stereotypes.

- PA can contribute to improving social status: non-disabled people see physically active individuals with disabilities more favourably than non-active people.

- The inherent nature of numerous sports activities fosters enhanced social integration, bonding, and the formation of friendships, thereby resulting in various social benefits.

- Fun:

- PA leads to mood benefits.

- Enjoyment through social interaction of both fitness staff and other participants.

Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Despite the health benefits, social context and fun, there are, depending on age and type of disability, barriers at an individual, social, environmental and policy level[23]:

Individual: lack of knowledge about where to exercise; lack of accessible knowledge/information about physical activity: what benefits there are to being active[24], how much activity should one do, and how safe is physical activity; fear of falling; the nature of the impairment producing pain during activity; lack of energy, lack of motivation, shame from being disabled;[9]personal concerns about safety; apprehension of attracting unwanted attention.

Social: dependency of children with disabilities on parents; over-protective others (caregivers, spouses, family); Physical Education teachers lack professional preparation or equipment to work with students with disabilities; doctors provide medical excuses for students with disabilities to avoid Physical Education; children with disabilities may have no friends to play with; inappropriate sports offered without suitable guidance; cost; limited social support; negative societal attitudes about disability from others (e.g. customers and staff at leisure centres).

Environmental: accessibility (too narrow gym doorways for wheelchair access, and inaccessible bathrooms or changing rooms); barriers in outdoor areas (e.g. poorly lit or wooded walking paths, traffic lights lack audible signals);[19] inadequate transportation; unsuitable equipment (e.g. no pool chair or arm cycles);[25] bad weather.

Policy / Programme: include barriers such as inaccessible or inappropriate or lack of specific programmes for people with disabilities or spinal cord injuries. Lack of staff or trained volunteers / lack of guidance from staff in how to exercise or adapt. Lack of appropriate equipment could also fall into this category. Policy or programme is the least reported barrier but still important. [26]

Physical Activity for Persons Living with Disability in Low-Income Countries[edit | edit source]

The majority of the research conducted on physical activity for persons with disabilities focuses on the general population and almost all data is generated from high-income countries. The future goal needs to include improved data collection in low-income and middle-income countries.[28] Based on the estimates from the Global Burden of Disease, visual impairment is a decisive factor in predicting years lived in disability in low and middle-income countries. A study conducted by 10/66 Dementia Research Group between 2003 and 2005 in 7 low and middle-income countries, including China, India, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Mexico, and Peru has found that dementia was a primary reason for disability, followed by stroke, limb impairment, arthritis, depression, eyesight problems and gastrointestinal impairments.[29] A direct link between poverty and disability was supported in the systematic review of the studies conducted in low and middle-income countries.[30]

Participation in physical activity among people with disabilities living in low-income countries has not been well studied and data is very limited.[28] Based on the comprehensive studies conducted in 46 low- and middle-income countries, persons with chronic physical conditions and over the age of 50 were less likely to meet physical activity guidelines than adults without those conditions.[31] Symptoms associated with chronic conditions such as depression, pain and difficulties with mobility were found to be barriers to living an active life.[31]

Health Care Provider[edit | edit source]

Guideline[edit | edit source]

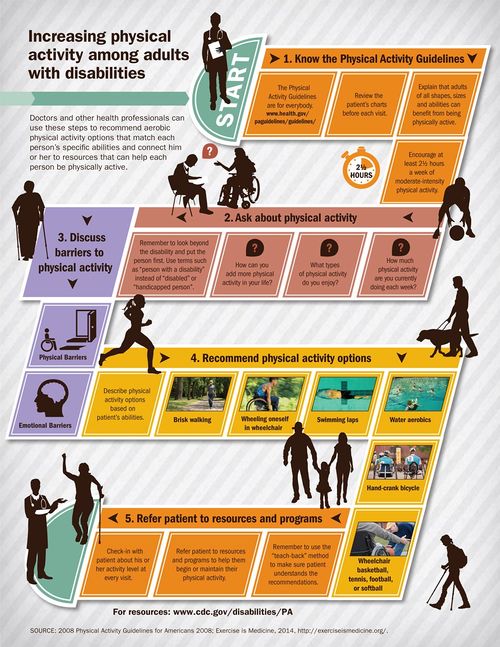

It is essential for physiotherapists and other health professionals to know the general Physical Activity Guidelines, as they are also applied for individuals with disabilities. Adults with disabilities are more likely to be physically active if it is recommended by doctors. Thus, if they received a PA recommendation, they were 82% more likely to be physically active than those who were not recommended PA.[32] Physiotherapists and other health professionals can use the 5 steps illustrated in the graphic below to increase physical activity among individuals with disabilities:

Interaction[edit | edit source]

General points you can consider when interacting with individuals with disabilities:

- If you are unsure about what to do when interacting with your patient, ask

- Speak directly to your patient instead of addressing a companion or interpreter when present

- Respect your patients’ assistive devices such as crutches or wheelchairs as their personal property that normally should not be moved unless you have permission

- Consider the extra time it may take your patient to transfer or prepare

- Never assume your patient needs your help. Offer your assistance and wait for a reply and specific directions

- Avoid making general assumptions, but instead try to get to know your patient’s individual needs, preferences and abilities.[17]

- Do not lean, touch, or adjust a person's wheelchair without their permission as it is considered an extension of their body.

Promoting Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Exercises[edit | edit source]

Find here factsheets describing various disabilities and health conditions, as well as physical activity, exercise, and overall health considerations and recommendations associated with each condition.

Inclusive Fitness Trainer[edit | edit source]

In the United States, an Inclusive Fitness Trainer (certified by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD), is a fitness professional who is uniquely qualified to work with people who have health risks and/or physical limitations. They have an understanding of the current Anti-Discrimination Act Policy and create adapted exercise programming that promotes safe and effective training. The aim is to empower individuals with disabilities to achieve their fitness goals.[33]

Campaign: How I Walk[edit | edit source]

"How I Walk aims to redefine the concept of walking by questioning both personal and societal viewpoints. This initiative serves as a rallying cry to encourage the practice of walking and the creation of pedestrian-friendly communities."[2]

Special Olympics and Paralympics[edit | edit source]

Special Olympics is the world largest sports organisation for people with intellectual disabilities. There are programs in 169 countries with more than 4.7 million athletes and over a million volunteers. Through the joy of sport, it aims to transform lives and to create a new world of inclusion. [34]

The Paralympic Games is one of the largest international sporting events. The first official Paralympic Games dates back to 1960 where 23 countries participated. 162 nations were represented at the 2020 Summer Paralympics.

Sport Organisations[edit | edit source]

Promoting Physical Activity in Low-Income Countries[edit | edit source]

Campaigns promoting physical activity in low-income countries must include:

- Lifestyle factors

- Physical health outcomes

- Economic restraints

- Sustainable primary and secondary interventions.[31]

Proposed strategies are:

- Education on the importance of physical activities

- Medical staff training in assessing physical activity levels

- Employment of cognitive behavioural principles, such as goal setting, problem-solving when discussing the importance of physical activities

- Development of a diverse group of practitioners: trainers, researchers and behavioural clinicians

- Stepped-care approach starting with self-management. If this approach fails, continue with a supervised, manualised approach conducted by a non-specialist worker, followed by activities with a specialist-supervisor if pain or mobility problems prevent completion of activities

- Efficacy trials of physical activities interventions

- Conducting cost-benefit analysis in order to quantify financial implications and choose resources appropriately followed by policy-level research

- Government engagement in increasing public awareness of the importance of physical activities

- Government engagement in providing an appropriate environment for physical activity.[31]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Facts & Figures: Disabilities in developing countries. SciDevNet 2019. Available at: https://www.scidev.net/global/features/facts-figures-disabilities-in-developing-countries/. Accessed 15.11.2021

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 NCHPAD. How I Walk. About How I Walk. 2015 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.nchpad.org/howiwalk/

- ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. People with disabilities in Australia. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-australia/contents/people-with-disability/prevalence-of-disability. Accessed 14.11.2021

- ↑ The World Bank. Disability Inclusion. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability. Accessed 14.11.2021

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability Overview. 2015 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

- ↑ Rimmer JH, Schiller W, Chen MD. Effects of disability-associated low energy expenditure deconditioning syndrome. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012 Jan;40(1):22-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 US Department of Health and Human Services. I can do it you can do it. 2017 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.fitness.gov/participate-in-programs/i-can-do-it-you-can-do-it/

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing Physical Activity among Adults with Disabilities. 2016 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/pa.html

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 de Hollander EL, Proper KI.Physical activity levels of adults with various physical disabilities.Preventive Medicine Reports 2018; 10:370-376

- ↑ Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985 Mar-Apr;100(2):126-31.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 WHO. Physical Activity Fact sheet [Internet]. 2021. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/. Accessed 14.11.2021

- ↑ WHOa. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity [Internet]. 2017 [cited 23/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/

- ↑ JPhysical Activity in Disabled Person. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kkPCPA5oUSg [last accessed 14/11/2021]

- ↑ Mendes MdA, da Silva I, Ramires V, Reichert F, Martins R, Ferreira R, et al. Metabolic equivalent of task (METs) thresholds as an indicator of physical activity intensity. 2018,PLoS ONE 13(7): e0200701.

- ↑ Sylvia LG, Bernstein EE, Hubbard JL, Keating L, Anderson EJ. Practical guide to measuring physical activity. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 Feb;114(2):199-208.

- ↑ Gov.uk. Inclusive language: words to use and avoid when writing about disability. 2014 [cited 23/02/2017]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/inclusive-communication/inclusive-language-words-to-use-and-avoid-when-writing-about-disability

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 NCHPAD. fckLRfckLRDisability Awareness: Interaction Tips for the Fitness Professional. General Rules. 2017 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.nchpad.org/615/2567/Disability~Awareness~~Interaction~Tips~for~the~Fitness~Professional

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability Overview. 2015 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Martin JJ. Benefits and barriers to physical activity for individuals with disabilities: a social-relational model of disability perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation 2013; Researchgate

- ↑ Thomas C. How is disability understood? An examination of sociological approaches. Disabil Soc 2004;19:569–83.

- ↑ WeThe15. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHCDvdCaJhI [last accessed 14/11/2021]

- ↑ Mohamed Galal. Benefits of sport and physical activity for the disabled. Available from: Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2-LSUF7-TU [last accessed 15/11/2021]

- ↑ Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB, Dekker R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. 2014. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 24 (6), 871-881

- ↑ Wadey R, Melissa Day M. A longitudinal examination of leisure-time physical activity following amputation in England.Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2018; 37: 251-261

- ↑ Smith B, Sparkes AC. Disability, sport, and physical activity. Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies (2nd edition) 2019. Routledge, London: 391-403.

- ↑ Vermaak, C. Spinal Cord Injury - Benefits, Barriers and Guidelines for Physical Activity. Plus Course. 2022

- ↑ Judson Laipply. The Evolution of Dance. Available from: Beyond empower. Breaking Barriers - Equipment as a barrier to disabled people keeping active. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CfcZgprOnIk [last accessed 15/11/2021]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Martin Ginis KA, van der Ploeg HP, Foster Ch, Lai B, McBride CB, Ng K et al. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: a global perspective. The Lancet. Series: Physical activity, 2021, 398(10298): 443-455.

- ↑ Sousa RM, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Albanese E, Guerra M, Huang Y et al. Contribution of chronic diseases to disability in elderly people in countries with low and middle incomes: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Lancet 2009;374:1821-30

- ↑ Banks LM, Kuper H, Polack S. Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017;12(12): e0189996.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Vancampfort D, Koyanagi A, Ward PB, et al. Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity and physical activity across 46 low- and middle-income countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017; 14: 6.

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adults with Disabilities - Physical activity is for everybody. 2014 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/disabilities/

- ↑ ACSM. ACSM/NCHPAD Certified Inclusive Fitness Trainer. 2015 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: http://certification.acsm.org/acsm-inclusive-fitness-trainer

- ↑ Special Olympics. What We Do. 2017 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.specialolympics.org/Sections/What_We_Do/What_We_Do.aspx