Prevention and Management of Occupational Related LBP

Original Editors

Lead Editors

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

In 2009, the United States Department of Labor[1] reported that the back was injured in nearly 50% of all musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) cases and required a median of 7 days to return to work. It is also reported that in the United States approximately 100 million days are lost from work per year because of low back pain (LBP).[2] Acute pain is typically pain present in the first month whereas chronic pain usually presents longer than 3 months.[3]

Work-related low back pain (WRLBP) is a major cause of work absenteeism and accounts for a high proportion of occupational disability costs[3]. Workers' compensation claims for LBP account for 70% of all compensation costs. Surprisingly, this percentage only accounts for 7% of all LBP cases. Another important factor associated with WRLBP is the psychosocial element. In people with acute WRLBP, the individual opinion on whether or not they would return to work was most predictive of who would be off work for 4 weeks after the onset.[4]

The greatest psychosocial predictor of prolonged work restrictions is the work subscale of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) with a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.08 for scores less than 30 and positive likelihood ratio (+LR) of 3.33 for scores greater than 34.[5] The FABQ is used to quantify the level of fear of pain and beliefs about the need to change behavior to avoid pain in individuals with LBP.[5] Godges et al.[4] also agrees with the strong correlation of FABQ and days missed from work. See Table 1.[4]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Approximately one-third of American workers are at increased risk of developing back disorders secondary to their jobs.[6] The United States Department of Labor[1] reported back pain to be the leading event or exposure to those working as nursing aides, orderlies, attendants, laborers and freight, janitors, cleaners, and most all truck drivers ranging from 44.9% to 59.2% of total injuries of all MSD. According to Chou et al.[7], approximately 2% of the U.S. work force compensated for back injuries each year resulted in tremendous indirect costs related to time lost from work.

One of the most commonly cited risk factors of occupational related LBP is sitting. Other risk factors may include heavy physical work, heavy or frequent lifting, combined postures with rotation and flexion, pushing and pulling, and exposure to whole body vibration (WBV) such as motor vehicle driving.[6][8]

According to Shaw et al.[9], back disability is highly associated with seven variables:

1. Work that involves heavy physical demand

- Bending, lifting, pushing, or pulling heavy objects for a long period of time at work

2. Inability to modify work

3. Stressful work demands

- Time pressure, productivity demand, and inability to control the speed of work

4. Lack of workplace social support+

- Isolated work environment, unusual working hours, new place of employment, recent departmental transfer, past conflicts with coworkers/supervisors, or difficulty developing social ties in the workplace

5. Job dissatisfaction+

- Unrewarding few prospects for transfer or advancement

- Overall discontent for the job

6. Poor expectation of recovery and return to work

7. The fear of re-injury

+ These have also been confirmed by Waddell et al.[10] as psychosocial aspects that contribute to increased time off work.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Occupational related LBP characteristics include factors such as age, gender, and duration of service with an individual's employer. The United States Department of Labor[1] addressed the characteristics of those requiring days away from work after suffering occupational injury and illness.

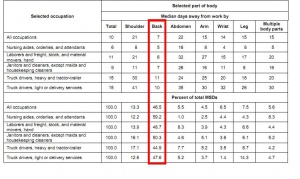

The following chart includes back injury incidence rates per 10,000 full-time workers at private industry, state government, and local government jobs in 2009. Percentages based on total amount of MSD.[1]

| Age (years) |

Gender | |||

|

16-19 20-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+ |

14.5% 21.0% 24.1% 26.8% 24.1% 18.0% 14.9% |

Male Female |

25.3% 20.1% | |

Further classification of LBP can be provided by using the Treatment-Based Classification (TBC) System. There are four typical presentations of mechanical (nonspecific) LBP, which are defined by this system.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The differential diagnosis of LBP can often times be difficult. The cause of LBP can stem from a number of conditions including cancer, spinal infection, ankylosing spondylitis, cauda equina syndrome, compression fracture, symptomatic spinal stenosis, or herniated disc with radiculopathy. It can also be caused by referred pain from several internal organs.[12] Other factors that are less severe, such as those who are pregnant, have fibromyalgia or myofascial pain syndromes, osteoporosis, or use steroids, may be at risk for experiencing LBP.[7] Therefore, it is important for clinicians to determine if the patient's pain is mechanical or resulting from an underlying cause.

Examination[edit | edit source]

According to Fritz et al.[11], measurements of impairments, pain, disability and psychosocial measures should be assessed to determine the appropriate intervention. Impairments can be measured in the history and physical examination. Pain is measured with Visual Analog Scale, disability is measured with the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), and psychosocial factors are measured with FABQ.

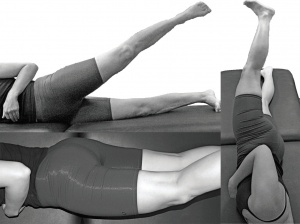

Nelson-Wong et al.[13] developed a screening tool to assess trunk control while performing a simple movement to predict the chances of the occurrence of occupational LBP. The active hip abduction (AHAbd) test provides a general assessment of an individual's ability to maintain trunk and pelvis alignment during lower extremity movement when placed in an unstable position. The AHAbd test has been tested in groups without LBP and has shown to yield measurements with some reliability and validity (Sp = .92, +LR = 4.59).[13]

Examination of a patient with occupational related LBP should follow a typical lumbar examination.[14] (click on LQScreenCompendium.pdf link)

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

A multidisciplinary team of occupational health professionals exists in order to provide the best care possible for patients experiencing illness and/or injury related to their work. The role of occupational physicians is of importance because they have to be able to manage patients with occupational related LBP in order to return them to work in a timely manner. However, this remains a challenge for these physicians.[15]

According to the Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA)[16], occupational health care physicians work closely with employers in order to assist in achieving a safe and healthy work environment. They also work collaboratively with labor and management to reduce/prevent hazardous situations as well as create training programs to implement workplace health and safety.

Video provided by: McLeod Health Center[17]

Pharmacological Management (current best evidence)

[edit | edit source]

In a study by Chou[12], it was stated that a medication does not exist to show results in large average benefits on LBP. A systematic evidence review performed by Chou et al.[7] found little evidence for medication use due to the limited benefits and risks associated with long-term use. Systemic corticosteroids, NSAIDS, tricyclic antidepressants, skeletal muscle relaxants, opiod analgesics, and antianxiety drugs all had little evidence of effectiveness for LBP.

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Educating patients with occupational LBP during treatment can impact the recovery time allowing patients to return to work within a reasonable time frame. Participants in the Godges et al.[4] study that were unable to return to work due to a work-related injury of LBP and had to score 50 points or higher on the FABQ were assigned to a comparison group or an educational group. The educational group was given the educational booklet Back Pain: How to Control a Nagging Backache that emphasized the importance of staying active, not letting the back pain control your life, understanding the pain cycle, gettting the pain under control, and how exercise and relaxation can help control pain. According to George et al.[18], The Back Book is another educational pamphlet that assists in reducing FABQ and disability in those with acute LBP. Education and counseling regarding pain management, physical activity, and exercise can reduce the number of days off work in this population with elevated fear-avoidance beliefs and acute LBP.[4] Participants in the comparison group took longer than those in the educational group to return to work.

PREVENTION

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)[19] compiled a review of scientific literature and concluded a lack of evidence for supporting or recommending use of back belts to prevent injuries. NIOSH provides a back belt educational pamphlet for additional information. A systematic review by Ammendolia et al.[20] provided additional evidence from a combination of observational studies, clinical trials, and RCT's indicating limited benefits of using a back belt unless the worker presents with a prior history of LBP. Laboratory evidence suggested that if prescribed, back belts should only be used short-term due to possible adverse effects such as cardiovascular complications. Further demonstration on proper lifting techniques without back belt see Video.[21]

Sitting has become the most common posture in the workplace in the United States and approximately three-quarters of all workers in industrialized countries have jobs that require sitting for long periods.[6] Many biomechanical studies have been performed to determine the effects on the low back in sitting. Though there is some debate, one common finding is that intrathecal pressure is increased in the seated posture and aggravates discogenic LBP.[6][2] Another finding reported is that during sitting, high pressure is found at the ischial tuberosities which is associated with high load to the spine.[2]

OSHA[16] suggests for a computer workspace there are four things to look at regarding the chair to prevent LBP.

These four suggestions are:

1. Backrest

- Lumbar support

- If no lumbar support, use a rolled up towel or a removable back support

2. Seat

- Feet flat on ground or use footrest for stable support

- Knee slightly higher than the seat

3. Armrest

- Supports forearm and elbow

- Keeps arms close to the trunk

4. Base

- Strong, five-legged base

Makhsous et al.[2] confirmed that sitting with decreased ischial support and back support reduced peak pressure under the tuberosities, reduced muscular activity, maintained proper lordosis, increased intervertebral disc heights, which could potentially reduce LBP.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Occupational related LBP can be prevented and managed appropriately if a multidisciplinary approach is utilized and can address an individual's impairments, pain, disability and psychosocial factors. By addressing these factors, workers' compensation claims can be reduced, as well as days absent from work. Treatment targeting workplace functional concerns, activity avoidance, and adherence to an appropriate intervention, including educational and physical factors, are key to improving an individual's return-to-work goals.[9]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Effects of education on return-to-work status for people with fear-avoidance beliefs and acute low back pain.This research report described the importance of education and counseling for patients with an elevated FABQ. Two groups included in the study both receive PT intervention. One of the groups received additonal education and counseling on pain management tactics. The study concluded that the education group had a reduce number of day of off work and quicker recovery.

Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work: The Bureau of Labor Statistics emphasizes different musculoskeletal disorders and the cases reported, incidence rates for different job types and characteristics of workers, equipment and events increasing exposure, and frequencies of sprains, strains, and tears occuring in work related injuries and illnesses.

Association between sitting and occupational LBP: This research was performed to determine the biomechanical effects of sitting in a chair with reduced ischial support and increased low back support. By using pressure mapping systems, the researchers determined that by decreasing the load on the ischial tuberosities and having a proper lumbar support there was potential to reduce low back pain occurrences.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/computerworkstations/components_chair.html

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work. United States: Department of Labor, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Makhsous M, Lin F, Hendrix RW, Helper M, Zhang L. Sitting with adjustable ischial and back supports: biomechanical changes. SPINE 2003;28(11):1113-1122.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Poitras S, Blais R, Swaine B, Rossignol M. Management of work-related low back pain: a population-based survey of physical therapists. Phys Ther 2005;85(11):1168-1180.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Godges JJ, Anger MA, Zimmerman G, Delitto A. Effects of education on return-to-work status for people with fear-avoidance beliefs and acute low back pain. Phys Ther 2008;88(2):231-239.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fritz JM, George SZ. Identifying psychosocial variable in patients with acute work-related low back pain: the importance of fear-avoidance beliefs. Phys Ther 2002;82(10):973-983.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Lis AM, Black KM, Korn H, Nordin M. Association between sitting and occupational LBP. Eur Spine J 2007;16:283-289.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. ACP 2007;147(7):478-491.

- ↑ Murtezani A, Hundozi H, Orovcanec N, Berisha M, Meka V. Low back pain predict sickness absence among power plant workers. Ind J Occup & Environ Med 2010;14(2):49-53.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Shaw WS, Main CJ, Johnston V. Addressing occupational factors in the management of low back pain: implications for physical therapy practice. Phys Ther 2011;91(5):1-13.

- ↑ Waddell G, Burton AK. Occupational health guidelines for the management og low back pain at work: evidence review. Occup Med 2001;51(2):124-135.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. JOSPT 2007;37(6):290-302.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chou R. Pharmacological management of low back pain. Drugs 2010;70(4):387-402.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Nelson-Wong E, Flynn T, Callaghan JP. Development of active hip abduction as a screening test for identifying occupational low back pain. JOSPT 2009;39(9):649-657.

- ↑ Wainner RS, Whitman J. USAF RSVP lower quarter screening examination. p. 1-32.

- ↑ Verbeek JH, van der Weide WE, van Dijk FJ. Early occupational health management of patients with back pain. SPINE 2002;27(17):1844-1851.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Occupational Safety & Health Administration. http://www.osha.gov/. Accessed April 26, 2011.

- ↑ McLeod Health. McLeod Health Informational Videos. http://www.mcleodhealth.org/Wellness/videos.cfm. Accessed April 27, 2011.

- ↑ George SZ, Bialosky JE, Fritz JM. Physical therapy management of a patient with acute low back pain and elevated fear-avoidance beliefs. Phys Ther 2004;84:538-549.

- ↑ National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/. Accessed April 26, 2011.

- ↑ Ammendolia C, Kerr MS, Bombardier C. Back belt use for prevention of occupational low back pain: a systematic review. JMPT 2005;28(2):128-134.

- ↑ Ayurvedic Healing. Back injury prevention – proper squatting lifting techniques. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jpqWRmD-INI. Uploaded December 21, 2009. Accessed April 26, 2011.