Public Involvement in Research

Introduction[edit | edit source]

PIR is a well-established and fundamental part of healthcare research globally. In recent years, interest and desire to involve the public in research and its impact on health care research has amplified[1]. This has largely been driven by a public desire to relate to research and funders of research seeking public benefit. Involving public and service users can be an integral part of the research process and aims to improve the quality, relevance and legitimacy of research, whilst also increasing the numbers of participants enrolling in studies[2]. It is worth noting that the increase in public involvement in health and social care research may highlight a social and power shift from research funders/researchers to the ‘people’ [3].

It has been suggested that PIR works best when using individuals with lived experience in the area being researched. This further supports the idea of patients/service users and the public being experience based experts who have invaluable and unique knowledge to complement the research and researchers. Additionally there is a strong argument to suggest that people who are affected by research have a right to what and how it should be undertaken. It has been proposed that involving members of the public can lead to the empowerment of people who most often use health and social care services and assist in influencing relevant and contemporary change and improvement within healthcare. PIR has the potential to assist future services to be used more appropriately and cost effectively and improve the quality of treatment for patients within the healthcare system. Having public involvement is now often a requirement of research proposals in order to apply or receive research funding in the UK from many organisations, such as National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)[4].

Definitions[edit | edit source]

There are multiple definitions used to describe PIR:

“research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them.” [5]

The “coming together of researchers and those affected by health conditions to work with each other in order to plan, design, implement, manage and disseminate research” [6]

The “carrying out of research with the integration of patients or members of the public in the study rather than the study being merely for or about the public” [7]

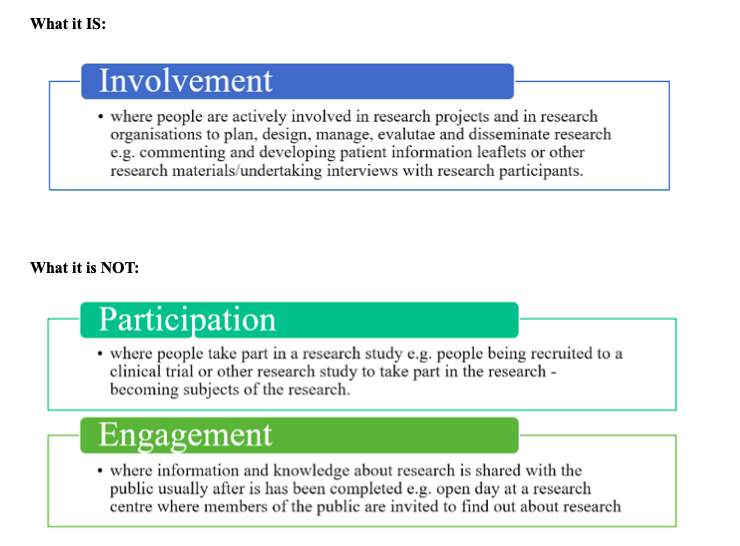

Distinguishing Between What PIR IS and What It Is NOT [5][edit | edit source]

Why People Get Involved[edit | edit source]

Personal Benefits[edit | edit source]

- People learn new skills

- Gain information about their health

- PIR enables recovery or it helps make sense of an illness experience

- People are sometimes unable to work because of illness or caring responsibilities and involvement offered a way of gaining confidence and experience.

- PIR can offer something interesting for people to do with their skills during retirement

- Personal satisfaction

- Opportunity to meet new people

Other Reasons Why to Get Involved[edit | edit source]

- Altruism - ‘Giving something back’ to the public as a whole, or to services

- Receive payment

- People hope to contribute to finding a cure for a condition/illness or a new treatment in the future

- To ensure that issues that are a priority for people are addressed

- Make good use of existing experience and knowledge

- Make sure research is asking the questions that are important to people who live with an illness or chronic condition

- To contribute to a better healthcare system through research

- To improve services for themselves and those who come after them; make care better for future patients/generations

- Sharing their knowledge, skills and experience from other related areas of work to the benefit of others

Benefits to Organisations Part-Taking in PIR[edit | edit source]

- Exploring the differences between professional and patient views and between corporate and community views

- Reduced health inequality

- Improved services

- Better understanding of the public’s needs

Who Do You Get Involved? [5] [8][edit | edit source]

- Patients

- Potential patients

- Carers and individuals who use health and social care services

- Individuals from organisations/groups who represent people who use these services

How to Find out About PIR[edit | edit source]

- The most common route is through having a particular illness or condition

- Involvement opportunities directly from staff caring

- Some people are inspired by taking part in medical research as a participant and then wanting to get more involved

- Some people take up other types of involvement first and then move into research

- Medical charities and support groups also provide a direct route to research involvement

- Having a family member who has been ill

Common Recruitment Methods of PIR [5][9][edit | edit source]

- Through the NHS (clinics, GP surgeries, outpatient departments), through the Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) Officer based at you local NHS Trust

- Contacting support groups, community/voluntary groups and charities

- Searching online for relevant organisations

- Advertising in local newspapers or on the radio

- Inviting existing patients or research participants

- Advertising on social media sites e.g. Facebook, Twitter

- Using personal connections/talking to other health and social care professionals - social workers, health visitors, community development workers

- Advertising on the ‘People in Research’ website

- Asking how existing PIR contributors find others

- Schools and youth clubs

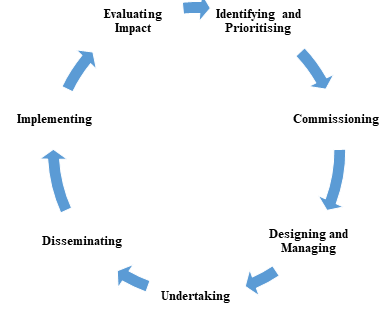

Ways That People Can Be Involved in the Different Stages of the Research Cycle[edit | edit source]

INVOLVE

Guidelines for PIR [4][edit | edit source]

The NIHR attempts to improve the incorporation of public involvement into research with every study required to describe their proposed methods of involving members of the public in ways other than being a participant. The NIHR suggest that authors should consider each of the following:

- If there was no public involvement in the study, please state this in your report, setting out why this was not thought appropriate or was not feasible

- What form did the PPI take and at what stages did it occur during your study?

- What impact did PPI have during the study? How was it useful?

- If there was little/no impact of PPI during the study, please say so

- The way(s) PPI will support dissemination of the results

The NIHR developed a checklist for authors to encourage public involvement and improve the standard of reporting PIR in studies which is called Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2). A short version of the form is shown below and for studies that are focusing purely on PIR, the full form can be accessed on: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/GRIPP2-long-form-Continued_tbl1_318863075. According to Staniszewska et al., (2017)[10] both the long and short version of the GRIPP2 are the first guidance checklists that are evidence based and aid in the reporting of PIR.

| Section and topic | Item | Reported on page No |

| 1: Aim | Report the aim of PPI in the study | |

| 2: Methods | Provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study | |

| 3: Study results | Outcomes - Report the results of PPI in the study, including both positive and negative outcomes | |

| 4: Discussion and conclusions | Outcomes - Comment on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall. Describe positive and negative effects | |

| 5:Reflections/ critical perspective | Comment critically on PPI input in the study, reflecting on the things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from this experience |

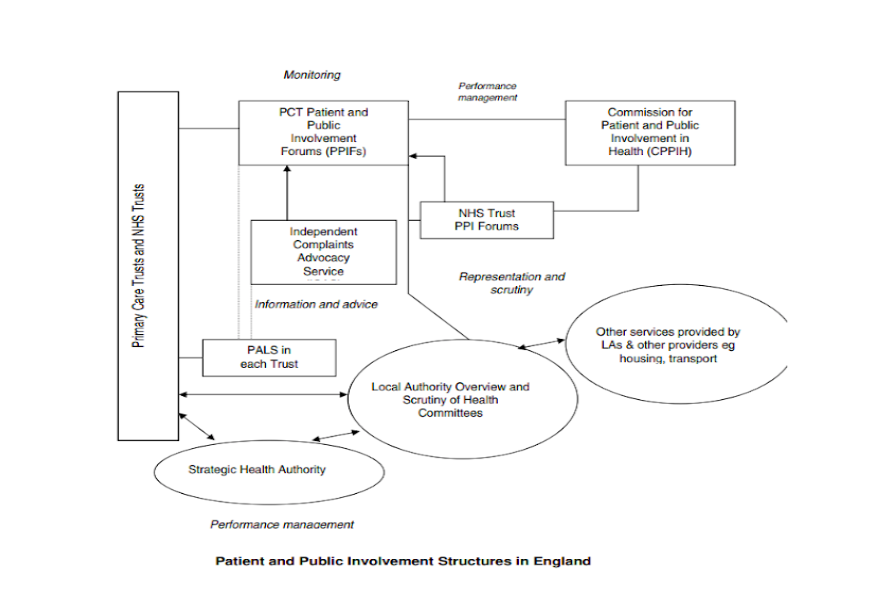

The current structure of PIR is outlined below as shown on a handbook designed by the HCPC[11]:

Different Types of Involvement [5][12][edit | edit source]

How researchers involve the public in the research process will depend on the nature of the study design/research topic and the activities members of the public want to be involved in. There are many different ways that involvement can occur in research and whilst there is often overlap, it can be helpful to think of the approaches as described below:

| Type of involvement | Definition/what that means |

| Consultation | Consultation is when you ask members of the public for their views and use these views to inform your decision making. Consultation can be about any aspect of the research process – from identifying topics for research through to thinking about the implications of research findings. |

| Collaboration | Collaboration involves an ongoing partnership between you and the members of the public you are working with, where decisions about the research are shared. For example, members of the public might collaborate with the researchers on developing the research grant application, be members of the study advisory group and collaborate with researchers to disseminate the results of a research project. |

| User Led Research | There is some disparity Some service users make no distinction between the terms user controlled and user led, others feel that user led has a different, vaguer meaning. They see user led research as research which is meant to be led and shaped by service users but is not necessarily controlled or undertaken by them. Control in user led research in this case will rest with some other group of non-service users who also have an interest in the research, such as the commissioners of the research, the researchers or people who provide services. |

| User Controlled Research | User controlled research is research that is actively controlled, directed and managed by service users and their service user organisations. Service users decide on the issues and questions to be looked at, as well as the way the research is designed, planned and written up. The service users will run the research advisory or steering group and may also decide to carry out the research. |

Benefits vs. Barriers of PIR[5][edit | edit source]

| Benefits of PIR | Barriers of PIR |

| ● Bring first-hand knowledge and experience

● Add value and improve the quality of review ● Improve the readability/accessibility of written scientific information ● Wider dissemination of a review ● Assists with research to be more cost effective ● Improve relevance of research |

● Lack of funding

● Lack of understanding ● Potentially unwanted results ● Difficulties recruiting suitable and sustainable members of the public ● Challenges managing expectations ● Time consuming ● Members of the public having a lack of knowledge in relation to research (need training/support/education) |

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Arnstein’s Ladder

- National Standards for PIR

- Patient and Public Involvement A Handbook for the Health and Social Care Regulations (HCPC)

- INVOLVE Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research

- A Researcher’s Guide to Patient and Public Involvement (Oxford University)

- Who Should I Involve and How Do I Find People? (NIHR)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron-Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2011;24(1):28-38.

- ↑ Chambers R, Drinkwater C, Boath E. Involving patients and the public: How to do it better. Radcliffe Publishing; 2003.

- ↑ Green G. Power to the people: to what extent has public involvement in applied health research achieved this?. Research Involvement and Engagement. 2016;2(1):28.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 National Institute for Health Research.About Public Involvement [Internet]. National Institute for Health Research London, 2017. Available from: https://www.peopleinresearch.org/public-involvement/ [Accessed on 6th November 2019]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 INVOLVE Briefing notes for researchers: public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research [Internet]. Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/9938_INVOLVE_Briefing_Notes_WEB.pdf[Accessed on 5th November 2019]

- ↑ Parkinson’s UK. Patient and Public Involvement: A resource for researchers. [Internet] Available from: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk [Accessed on 4th November 2019]

- ↑ Hyde C, Dunn KM, Higginbottom A, Chew‐Graham CA. Process and impact of patient involvement in a systematic review of shared decision making in primary care consultations. Health Expectations. 2017;20(2):298-308.

- ↑ Gray-Burrows KA, Willis TA, Foy R, Rathfelder M, Bland P, Chin A, Hodgson S, Ibegbuna G, Prestwich G, Samuel K, Wood L. Role of patient and public involvement in implementation research: a consensus study. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2018;27(10):858-864.

- ↑ Turk A, Boylan A, Locock L. A researcher’s guide to patient and public involvement

- ↑ Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K, Mockford C, Goodlad S, Altman DG, Moher D, Barber R, Denegri S, Entwistle A. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. Research Involvement and Engagement. 2017;3(1):13.

- ↑ Prime R&D Ltd Patient and Public Involvement, A Handbook for the Health and Social Care Regulators [Internet] Available from: https://www.hcpc-uk.org/globalassets/meetings-attachments3/communications-committee/2006/february/communications_committee_20060227_enclosure07ii/ [Accessed on 3rd December 2019]

- ↑ Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy. 2002;61(2):213-36