Psoas Major

Original Editor - Oyemi Sillo

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Samrah khan, Lucinda hampton, Oyemi Sillo, Kim Jackson, George Prudden, Samson Chengetanai, Joao Costa, Maram Salem, Rachael Lowe and Kardelen Aktas;

Introduction[edit | edit source]

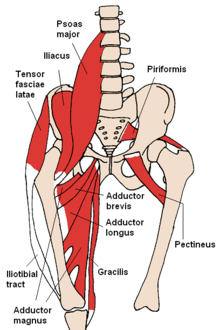

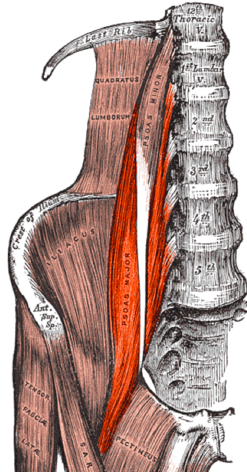

The psoas muscle is a paraspinal muscle located deep in the body. It lays close to the spine on either side and extends distally to the brim of the lesser pelvis. It combines with the iliacus muscle to form the iliopsoas muscle closer to the insertion point. Due to its proximity to the lumbar vertebrae, it plays an important role in back health. It also acts to both laterally flex the lumbar spine and assists with flexion and external rotation of the hip.[1] [2]It is essential for correct standing or sitting lumbar posture, stability of the hip joint, and during walking and running[3]. The psoas muscle is one of the core muscles.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Origin

The psoas muscle contains superficial and deep parts owing to the presence of branches of the lumbar plexus running through it. Superficially, it originates along the lateral surface of the distal thoracic vertebrae and adjacent intervertebral discs. The deeper portion originates at the first four lumbar vertebrae.[2]

Insertion

The fibres of the muscle converge from its wide origin as they descend on the posterior abdominal wall. They cross the pelvic inlet to form a long tendon, which is joined within the pelvic region by fibres from the iliacus muscle, finally inserting into the lesser trochanter of the femur.

Bursa

Below the insertional tendinous unit is the iliopsoas bursa, which separates the tendon from the bone surface and the proximal portion of the femur.

Fibre Types

In humans, the psoas major muscle fibres are mainly represented by anaerobic, fast oxidative (about 60%), while the remaining percentage consists of aerobic, slow oxidative (about 40%). This demonstrates the psoas muscle's important role in dynamic function and simultaneous role for postural support. At the site of its origin, there are more anaerobic fibres present for static (postural) function. Distally and closer to the insertion point, there are more aerobic fibres to assist with dynamic function[3].

Nerve Supply

Branches from the anterior rami of lumbar spinal nerves L1-L4 before they join to form the lumbar plexus. The lumbar plexus is embedded within the psoas major muscle and its branches emerge from it.[1]The psoas muscle also receives small branches from the femoral nerve.

Blood Supply

The muscle receives blood from the four lumbar arteries from the aorta, from small branches of the renal arteries, from small muscular branches of the common iliac artery, and from the deep circumflex iliac artery[4].

Function[edit | edit source]

The psoas major muscle functions as a static and dynamic muscle. It sits at a juncture between the upper and lower body. Due to its respective origin and insertion points, it also functions as a "front to back" muscle given its placement with various superior, medial, and inferior portions of fascial tissue as it descends through the pelvic cavity.

The psoas major combines itself with the iliacus muscle. With this contribution, it acts as a hip flexor in both supine and standing. When in a static position (sitting), it acts as a stabilizer for the lumbar spine. The psoas major muscle also stabilizes the femoral head within the acetabulum of the hip in the first 15 degrees of movement. [3]Since the psoas muscle has two segments, one each side of the body, it assist with lateral motions (unilateral side contraction) or with bilateral motions (both right and left psoas major contractions). An example of a bilateral motion is trunk elevation when transitioning from a supine to sitting/standing position.[1]

Since it inserts distally at the lesser trochanter of the femur, it acts as a hip flexor, hip adductor, and hip external rotator. When standing upright, unilateral contraction will yield flexion of the lumbar spine, sidebending the lumbar spine to the ipsilteral side with simultaneous contralateral rotation (e.g., left psoas major contraction will yield sidebending towards the left with rotation to the right).

Physiotherapy Relevance[edit | edit source]

Excessive periods of time in a sitting position can shorten the psoas muscle, causing myofascial pain, low back pain, and difficulty with maintaining a standing position. It may also cause the lumbar spine to arch back, as seen in lumbar hyperlordosis.[5] Loss of hip motion contributes to low back pain and disability.[6] Weakness or spasm of the psoas can cause subsequent restrictions with breathing or movement of the thoracic diaphragm.[7] A weakened psoas makes it difficult to flex the hip joint, resulting in difficulty ascending stairs, walking uphill, transferring from supine to sit, and standing up from a sitting position.[8] The psoas major muscle can be involved in acute groin injuries, often seen in athletes.[9]

Stretching the psoas major muscle can decrease low back pain and disability.[10]Treating loss of hip extension (as a result of a tight psoas major muscle) increases functional outcomes of patients and decreases overall painful symptoms. Due to the location of the psoas major muscle, spasm or tightness in this muscle can lead to subsequent pelvic pain. Psoas major release and stretching can assist patients exhibiting pelvic pain.[11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bogduk NP, Pearcy M, Hadfield G. Anatomy and biomechanics of psoas major. Clinical Biomechanics. 1992 May 1;7(2):109-19.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Siccardi MA, Tariq MA, Valle C. Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, psoas major.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, Iliopsoas Muscle.

- ↑ http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/psoas

- ↑ Penning L. Psoas muscle and lumbar spine stability: a concept uniting existing controversies: critical review and hypothesis. European Spine Journal. 2000 Dec;9:577-85.

- ↑ Redmond JM, Gupta A, Hammarstedt JE, Stake CE, Domb BG. The hip-spine syndrome: how does back pain impact the indications and outcomes of hip arthroscopy?. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2014 Jul 1;30(7):872-81.

- ↑ Tufo A, Desai GJ, Cox WJ. Psoas syndrome: a frequently missed diagnosis. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 2012 Aug 1;112(8):522-8.

- ↑ Very well health Psoas Muscle and Your Low Back Health Available:https://www.verywellhealth.com/psoas-muscle-and-your-low-back-health-297061 (accessed 16.1.2022)

- ↑ Serner A, Tol JL, Jomaah N, Weir A, Whiteley R, Thorborg K, Robinson M, Hölmich P. Diagnosis of acute groin injuries: a prospective study of 110 athletes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2015 Aug;43(8):1857-64.

- ↑ Avrahami D, Potvin JR. The clinical and biomechanical effects of fascial-muscular lengthening therapy on tight hip flexor patients with and without low back pain. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2014 Dec;58(4):444.

- ↑ Lifshitz L, Sela SB, Gal N, Martin R, Klar MF. Iliopsoas the hidden muscle: anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2020 Jun 1;19(6):235-43.