Annular Ligament

Original Editor - Ahmed Essam

Top Contributors - Ahmed Essam, Rucha Gadgil, Rosie Swift and Wanda van NiekerkAttachment[edit | edit source]

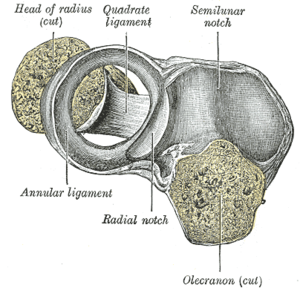

It runs around the radial head from the anterior and the posterior margin of the radial notch, to approximate the radial head to the radial notch and enclose the radial circumference. It encircles 80% of the radial head and functions to maintain the relationship between the head of the radius and the humerus and ulna. The external surface of the ligament receives attachments from the elbow capsule, the radial collateral ligament, and the supinator muscle.[1]

Function[edit | edit source]

- Holding the proximal radius against the ulna as it fits strongly around the radial head,

- It permits for free rotation of radial head as it's internal surface is lined with cartilage.

Clinical significance[edit | edit source]

A strenuous pull on the forearm through the hand can cause the radial head to slip through the distal end of the annular ligament. Medically this is known as "Radial Head Subluxation" but it is commonly called 'Pulled elbow' or "Nursemaid's elbow".

Young children are particularly susceptible to Radial head subluxation. It is the most common cause of upper extremity immobility in preschool children[2], and is more common in girls and in the left arm[3]. It is caused by axial traction or a sudden pull of the extended pronated arm. The radial head moves out of the weak annular ligament and capitellum, resulting in slipping over and subluxation of the radial head into the supinator muscle and annular ligament.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Typical history might include a sharp jerk to the arm. This could include:

- lifting the child by one arm

- a child and an adult holding hands and rapidly changing direction whilst still holding hands

- pulling an arm through the sleeve of a sweatshirt

- the child tossing and turning with his or her arm under the body[4]

The child will complain of pain and typically hold the arm immobile with the elbow fully extended and the forearm pronated; any attempt to supinate the forearm is resisted. No obvious swelling or deformity can be seen in the injured elbow.

The diagnosis is essentially clinical based on the mechanism of injury, although radiographs are usually obtained to exclude fracture (supracondylar humeral fractures are often missed), dislocation, and other bony abnormalities such as osteochondritis dissecans[4].

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Closed reduction of annular ligament subluxation is performed for the majority of cases. Clinicians must be certain no fracture is present prior to any manipulation. This procedure can be carried out within an office medical setting, or may be carried out by a parent/caregiver in the event of frequent Radial head subluxations.

Open reduction is rarely required, although may be considered for chronic, symptomatic subluxations that cannot be reduced[5].

Closed reduction of annular ligament subluxation [edit | edit source]

Two techniques are commonly described and result in immediate reduction if effective. The hyperpronation technique has been found to be more effective than the supination-flexion technique[4].

- hyperpronation technique

The physician holds the child’s elbow at 90° with one hand while firmly pronating the child’s wrist with the other. The physician’s thumb applies pressure over the radial head and a palpable click is often heard with reduction of the radial head.

- supination-flexion technique

The physician holds the child’s elbow at 90° with one hand while rapidly supinating the child’s wrist and flexing the elbow with the other

Following the procedure the child should begin to use the arm within minutes after reduction. Immobilization is unnecessary if the subluxation relocates on the first attemp[4]t. One of the best ways to prevent this dislocation is to explain to parents/caregivers that a sharp pull on the child’s hand can cause the subluxation.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bozkurt M, Acar H, Apaydin N, Leblebicioglu G, Elhan A, Tekdemir İ et al. The Annular Ligament. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;33(1):114-118.

- ↑ Schutzman SA, Teach S. Upper-extremity impairment in young children. Annals of emergency medicine. 1995 Oct 1;26(4):474-9. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

- ↑ Vitello S Dvorkin R Sattler S Levy D & Ung L. Epidemiology of nursemaid’s elbow. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014.15(4) 554. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Yamanaka S, Goldman RD. Pulled elbow in children. Canadian Family Physician. 2018 Jun 1;64(6):439-41. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

- ↑ Triantafyllou S, Wilson S & Rychak J. Irreducible" pulled elbow" in a child. A case report. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 1992. (284), 153-155. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

- ↑ Nursemaid's Elbow. Larry Mellick available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJb5rGOFiTY