Burn Wound Healing Considerations and Recovery Care Interventions

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring and Jess Bell

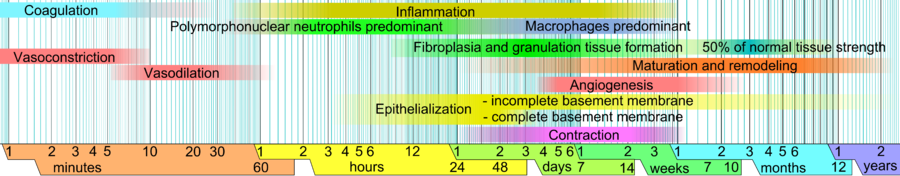

Burn Wound Healing Physiology[edit | edit source]

Please see this document for a growing list of wound care terminology and definitions.

Epithelialisation[edit | edit source]

Epithelialisation is "a process of covering defect on the epithelial surface during the proliferative phase that occurs during the hours after injury. In this process, keratinocytes renew continuously and migrate upward from the basal to the differentiated layers. A continuous regeneration throughout homeostasis and when skin injury occurs is maintained by the epidermal stem cells ... Epithelialization is the most essential part to immediately reconstruct skin barrier in wound healing where keratinocytes undergo a series of migration, proliferation and differentiation."[1]

Superficial partial thickness wounds:

- epithelialisation occurs as the proliferative phase comes to an end, and the remodelling phase begins

- there is a significant decrease in the amount of exudate released from the wound

- the risk of infection decreases

- initial epithelial resurfacing is a thin, single layer of keratinocytes which matures to a stratified, multi-cell layered structure that provides the barrier functions of the skin

- skin appendages (hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands) eventually return to normal functioning

- no granulation tissue is generated and, therefore, these burn wounds generally heal without scar formation

Burn injuries of indeterminate depth or deep partial thickness wounds:

- there is damage deeper into the dermal layer, and these injuries may destroy many of the skin appendages

- full thickness burns eliminate all of the dermal appendages

- healing of these burn injuries involves scar formation; these scars never regain the normal structure and function of skin (this is also true for areas of skin graft placement)

Burn Wound Care During Re-epithelialisation[edit | edit source]

"Care of the burn wound as it is re-epithelialising is critical to allow the new epidermis to resurface the burn and mature. Any trauma or changes in the wound environment may delay or prevent ongoing epithelialisation or cause deterioration of new epithelium." -- Diane Merwarth, Physical Therapist, Wound Care Specialist[2]

Wound Cleansing[edit | edit source]

Wound cleansing must be extremely gentle to avoid traumatising the new epithelium; gentle rinsing and patting of the wound are sufficient.

Dressing Selection and Techniques[edit | edit source]

Please consider the following:

- use non-adherent dressings that minimise evaporative water loss (taking care not to create a situation where the wound may be too wet)

- decreasing dressing change frequency minimises the risk of causing trauma to the fragile new epithelium

- ideally, dressing changes should be undertaken every 3-5 days, depending on the dressing being used, unless there are infection concerns

- discontinuing the use of silver-based dressings also facilitates the final resurfacing of the burn wound

- protection of the wound margins, including the new epidermis, will help keep dressings from adhering and avoid potential periwound maceration

- dressing application should be discontinued when there is no drainage on the dressings, and the wound area is visibly re-epithelialised

| Benefits | Risks | |

|---|---|---|

| Petrolatum-based gauze dressing

(eg Xeroform or Vaseline gauze) |

|

|

| Non-adherent foam dressing |

|

|

| Hydrocolloids |

|

May maintain a wound environment that is too moist |

| Transparent films | Allows for visual monitoring of the wound |

|

| Alginate dressings |

|

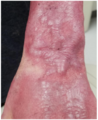

Burn Wound Complication: Maceration[edit | edit source]

Maceration (i.e. a softening of tissue caused by excessive moisture) is a common complication of burn wounds. Prolonged exposure to excessive moisture affects periwound skin. It causes it to be weakened and easily ruptured due to:[3][4]

- decreased elasticity and increasing brittleness of the epidermis

- decreased collagen density

- flattening of the basement membrane

- decreased binding of the basement membrane to the extra-cellular matrix

- impaired re-epithelialisation

All photos provided by and used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Prevention is the best intervention to avoid the complications associated with maceration:[2]

- appropriate dressing selection to manage drainage

- appropriate dressing change frequency

- protecting the periwound skin and any epithelial islands within the wound:

- applying an ointment, paste, emulsifier or liquid polymer to protect the skin from moisture exposure. Example: zinc oxide paste, petrolatum or antibiotic ointment

- placing a dressing or dry gauze between the digits or skin folds

Clinical Pearl: Zinc Oxide Paste[edit | edit source]

Zinc oxide paste is a commonly used mineral paste in the treatment of skin irritations. It is inexpensive and readily available in most places.[5] It can provide periwound protection against moisture and maceration. The thick white paste is opaque, which makes determining the periwound condition difficult.[2] The paste can affect the absorbency and adhesion of overlaying dressings.[5]

Zinc oxide paste is robust and adheres to the skin. Fortunately, it does not need to be completely removed at each dressing change:[2]

- the area can be gently wiped to remove the surface residue and crusted exudate

- if there is still adequate paste on the skin, it is not necessary to add more paste. If there are areas of sparse coverage, more paste can be added

- when protection of the skin is no longer indicated, any resistant paste can be removed by applying a layer of petrolatum and wiping the skin after a few minutes

Patients may have an allergy to this product. Please view this link for additional allergy information.

Post-healing Skin Care[edit | edit source]

After the skin has re-epithelialised, diligent care is required to protect the new epithelium.[2]

- Moisture retention and hydration

- it can take up to 1 year post-re-epithelialisation for these functions to be restored following superficial partial thickness burn injuries

- during the remodelling phase, hydrating creams or lotions can replace some of the moisture retention functions of the skin

- general recommendations for moisturising and / or hydrating skin: use a non-irritating fragrance-free cream or lotion specific for moisturising the skin

- Avoid exposure to ultraviolet rays

- increased risk of developing skin cancer

- sun protection recommendations: use a sunscreen of at least 50 SPF and cover the newly-healed skin with clothing or a hat

- Decrease friction on new skin

- bathing: avoid aggressive scrubbing of the new skin while washing and drying

- application of moisturisers: done with minimal friction - it is not necessary to completely rub the cream or lotion into the skin, as it will be absorbed very quickly into the dry skin

- clothing selection:

- avoid any tight clothing over the burn wound area

- avoid wearing any clothing made of rough fabric

- recommend well-fitting shoes

- typical recommendations: wear loose, soft clothing; socks should always be worn with shoes

- Activity and nutrition

- a burn injury results in a persistent hypermetabolic state, which requires sufficient caloric intake to support metabolism

- a consultation with a dietitian or nutritionist is recommended

- fatigue is a common side effect associated with the energy requirements of this hypermetabolic state

Post-burn Wound Injury Care and Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Physical Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

"The rehabilitation for patients with burn injuries starts from the day of injury, lasting for several years and requires multidisciplinary efforts."[6]

Physical rehabilitation plays a vital role in improving functional independence and ability and maintaining medical status. It also has a positive influence on emotional and psychological well-being. Physical rehabilitation in post-burn wound injury care can include:

- maintaining range of movement

- minimising the development of contracture and the impact of scarring

- prevention of deformity

- maximising psychological well-being

- maximising social integration

- maximising functional ability and recovery

- enhancing quality of life

Please read this article to learn more about post-burn wound injury physical rehabilitation.

Burn Scar Management[edit | edit source]

"Hypertrophic scar formation is a significant debilitating factor following a burn injury. For burn survivors who suffer deep-partial or full thickness injuries, development of hypertrophic scars is inevitable. Damaged or destroyed extracellular matrix is unable to regenerate, and therefore can’t provide the components needed to regenerate the epithelium. The excessive and prolonged inflammatory response that is normal to burn injuries results in the production of immature collagen." -- Diane Merwarth, Physical Therapist, Wound Care Specialist[2]

Hypertrophic scar characteristics:[7]

- elevated, firm, and erythematous in appearance

- pruritic (itchy) and tender for the patient

- limited to the site of the original burn wound injury

- grow in size by pushing out the scar margins

Additionally, because the epidermis does not regenerate, the normal functions of the skin are not restored:[2]

- loss of sweat glands, which diminishes thermoregulation in the involved area

- sebaceous glands are not available to provide lubrication to the skin and hair follicles

- pliability/elasticity of the skin and soft tissue is severely diminished which directly contributes to scar contracture and limited functional range of motion

- can be considered aesthetically unappealing by burn survivors

- coverage with a skin graft can mitigate some of the complications of hypertrophic scars

All photos provided by and used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Hypertrophic Scar Non-invasive Management[edit | edit source]

Hypertrophic scars are a dominant type of pathological scar formation after burns. Nowadays, hypertrophic scarring is described as “the greatest unmet challenge after burn injury.”[7]

A 2023 report determined that there is no consensus for any single intervention in the management of hypertrophic scars.[8] As with all areas of rehabilitation practice, clinician experience and clinical reasoning play a huge role in setting and reassessing a burn injury care plan. Mentorship and coordination within the interdisciplinary care team should be used to support the wound care professional.

- Silicone gel:

- silicone gel (pieces of thin, flexible-medical grade silicone that can come in a sheet or as a self-drying gel) can be placed over hypertrophic scars

- can be used alone or underneath pressure garments, splints, or casts[9]

- scar quality improvements may be more significant when silicone use is combined with pressure garment therapy (see below) when used on hand injuries[11]

- the mechanism of treatment is based on silicone's ability to restore the skin's barrier function by reducing transepidermal water loss

- restoration of this barrier can take at least a year in deep-thickness burn wounds[12]

- despite a lack of strong evidence, many burn care algorithms and protocols include silicone as the first or primary therapy in scar management[2]

- the American Burn Association states there are "no clear benefits to using gels versus gel sheets or nonsilicone versus silicone products with respect to the treatment effect, but there appear to be fewer adverse reactions when using silicone gels compared to gel sheets"[13]

- some patients may have an allergy or sensitivity to silicone, so skin checks should be performed frequently[9]

- Massage therapy:

- recent research states that massage therapy can provide significant short-term improvement on burn scars, but no long-term benefit was appreciated[2]

- may have some positive effects on patient-reported pruritis, pain, and vascularisation,[14] but no current evidence shows a lasting effect on scar height or thickness[2]

- Pressure garment therapy (PGT):

- PGT has been extensively studied for the management of burn scars,[2] and is considered the mainstay non-invasive treatment for hypertrophic scars[12]

- it is theorised that the mechanical forces applied by the pressure garments decrease scar contracture and reorganise collagen deposition during the remodelling phase[12]

- PGT has been found to be capable of improving scar colour, thickness, pain, and scar quality[15]

- wearing schedules for pressure garments have not been standardised, with research suggesting a wearing schedule anywhere from 4 hours blocks to a continuous 23[15] or 24 hours/day, with garments being removed for bathing purposes[2]

- the ideal pressure for PGT also varies in the research: some reports show the ideal pressure exerted by garments is 15-25 mmHg, while other studies recommend a pressure that equals or exceeds capillary closing pressure (40 mmHg)[2]

- garment fatigue (garment in need of replacement) significantly decreases the effectiveness of PGT[2]

- outcomes are directly affected by poor patient adherence; reasons reported for poor adherence include:[2]

- garments are uncomfortable or hot to wear as scheduled

- garments can be difficult to don and doff

- cost is a significant deterrent to obtaining and replacing fatigued garments

- Corticoid-embedded dissolving microneedles (CEDMN):

- CEDMN provide minimal to painless skin penetration and direct dermal drug delivery using a hyaluronic acid dressing onto which the microneedles are implanted.[16] As the microneedles dissolve, they release the embedded corticosteroid, which has been found to be effective in reducing the thickness of hypertrophic scars[2]

- this intervention holds great promise as being superior to intralesional steroid injections, which can be extremely painful and have a limited area of effectiveness[2]

- Serial casting:

- a small 2023[17] study found there was recovery of full range of motion using serial casting

- once full ROM is achieved, a night-time splint is used to maintain range of motion

- the casting protocol included therapeutic interventions to the joint at each cast change:[17]

- moist heat

- active range of motion with end-range stretching

- joint glides

- progressive resistive exercises

Hypertrophic Scar Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

If functional limitations or aesthetic concerns continue after maturation, surgery can be considered, such as:

- scar contracture release

- scar debulking

- cosmetic surgery

There is abundant research and case reports studying various interventions intended to improve outcomes related to hypertrophic scars. Unfortunately, the outcomes of these studies and reports are very variable.[2]

Burn Wound Injury Special Concern: Post-burn Pruritus[edit | edit source]

Pruritus, or itching, is a common and significant complication of burn injuries and can greatly affect a burn survivor's quality of life and psychosocial well-being.[18]

- onset may occur within a few days after burn injury and can persist for years after healing

- prevalence of pruritus immediately after burn is 80–100%; the prevalence rate continues to be approximately 40% 12 years post-burn injury

- sensory discomfort associated with pruritus can include: prickling, burning sensation, numbness, and stinging that occur in the post-burn state

- pruritus can be disruptive to sleep and affect an individual's ability to complete daily activities[18]

When considering treatment for pruritus, it is important to determine if underlying factors may be contributing to the itching. If the burn survivor has any of these factors, they should be addressed first before other pruritus interventions are initiated. These factors can include: (1) an allergy or sensitivity to their current drug therapy, (2) an underlying dermatological disorder, or (3) they may be developing a neuropathy.

The mechanism of pruritus is not well understood when it is directly related to the burn injury itself. Therefore, there is no accepted consensus for treatment. Treatments that show some success include:[2]

- topical treatment with creams, lotions or emollients to restore the barrier function

- systemic treatment

- antihistamines

- gabapentin

- gabapentin in combination with pregabalin (this combination was found superior to either used alone)

- antidepressants

- somewhat effective for patients with pruritis who also suffer from depression or anxiety

- extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT)

- physical treatment

- compression

- massage

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clincial Resources:[edit | edit source]

- Burn Physiotherapy and Occupations Therapy Guidelines (New South Wales Government)

- Practice Guidelines for the Application of Nonsilicone or Silicone Gels and Gel Sheets After Burn Injury (American Burn Association, 2015)

Patient/ Care Provider Education[edit | edit source]

- Burn Care at Home Handout Example (Trauma Burn Center, University of Michigan Health System)

- Eating Well for Wound Healing Handout Example (National Institutes of Health)

- Energy Conservation Handout Example (NHS Foundation Trust, Blackpool Teaching Hospitals)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Tan ST, Dosan R. Lessons from epithelialization: the reason behind moist wound environment. The Open Dermatology Journal. 2019 Jul 31;13(1).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 Merwarth D. Management of Burn Wounds Programme. Burn Wound Healing and Recovery Care Course. Plus, 2024.

- ↑ Dhandapani N, Samuelsson K, Sköld M, Zohrevand K, German GK. Mechanical, compositional, and microstructural changes caused by human skin maceration. Extreme Mechanics Letters. 2020 Nov 1;41:101017.

- ↑ Ter Horst B, Chouhan G, Moiemen NS, Grover LM. Advances in keratinocyte delivery in burn wound care. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2018 Jan 1;123:18-32.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schuren J, Becker A, Gary Sibbald R. A liquid film‐forming acrylate for peri‐wound protection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis (3M™ Cavilon™ no‐sting barrier film). International wound journal. 2005 Sep;2(3):230-8.

- ↑ Procter F. Rehabilitation of the burn patient. Indian journal of plastic surgery: official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2010 Sep;43(Suppl):S101.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Van Baar ME. Epidemiology of scars and their consequences: burn scars. Textbook on Scar Management: State of the Art Management and Emerging Technologies. 2020:37-43.

- ↑ Carney BC, Bailey JK, Powell HM, Supp DM, Travis TE. Scar management and dyschromia: a summary report from the 2021 American Burn Association State of the Science Meeting. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2023 May 1;44(3):535-45.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center. Scar Management After Burn Injury. Available from: https://msktc.org/burn/factsheets/scar-management-after-burn-injury (last accessed 18/April/2024).

- ↑ Tian F, Liu Z. Silicone gel sheeting for treating hypertrophic scars. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021(9).

- ↑ Pruksapong C, Burusapat C, Hongkarnjanakul N. Efficacy of silicone gel versus silicone gel sheet in hypertrophic scar prevention of deep hand burn patients with skin graft: a prospective randomized controlled trial and systematic review. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery–Global Open. 2020 Oct 1;8(10):e3190.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Shirakami E, Yamakawa S, Hayashida K. Strategies to prevent hypertrophic scar formation: a review of therapeutic interventions based on molecular evidence. Burns & trauma. 2020;8:tkz003.

- ↑ Nedelec B, Carter A, Forbes L, Hsu SC, McMahon M, Parry I, Ryan CM, Serghiou MA, Schneider JC, Sharp PA, de Oliveira A. Practice guidelines for the application of nonsilicone or silicone gels and gel sheets after burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2015 May 1;36(3):345-74.

- ↑ Santuzzi CH, Liberato FM, de Oliveira NF, do Nascimento AS, Nascimento LR. Massage, laser and shockwave therapy improve pain and scar pruritus after burns: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2023 Dec 9.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 De Decker I, Beeckman A, Hoeksema H, De Mey K, Verbelen J, De Coninck P, Blondeel P, Speeckaert MM, Monstrey S, Claes KE. Pressure therapy for scars: myth or reality? A systematic review. Burns. 2023 Mar 11.

- ↑ De Decker I, Szabó A, Hoeksema H, Speeckaert M, Delanghe JR, Blondeel P, Van Vlierberghe S, Monstrey S, Claes KE. Treatment of hypertrophic scars with corticoid-embedded dissolving microneedles. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2023 Jan 1;44(1):158-69.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Schetzsle S, Lin WW, Purushothaman P, Ding J, Kwan P, Tredget EE. Serial Casting as an Effective Method for Burn Scar Contracture Rehabilitation: A Case Series. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2023 Sep 1;44(5):1062-72.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Chung BY, Kim HB, Jung MJ, Kang SY, Kwak IS, Park CW, Kim HO. Post-burn pruritus. International journal of molecular sciences. 2020 May 29;21(11):3880.