Communication in Chronic Pain Conditions

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (10/05/2020)

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Acute pain conditions have a very good rate of healing, but health care systems still find that a large portion of these patients go on to experience persistent pain and maladaptive behaviours .[1],[2] As a result Persistent Pain conditions place a huge strain on the healthcare system and economy .[1] Modern pain research tells us that often patient beliefs play a huge role in the transition from acute pain to chronicity. By better understanding patient beliefs and positively influencing them with reassurance and compassion we can better manage patients perception of pain .[1],[3]

We know from nursing literature that pain is the most common reason for an individual to seek medical advice .[4] At times Healthcare Professionals can negatively impact patients beliefs about pain. It is common that some patients feel that their stories haven’t been listened to and consequently their pain is not validated .[5]

What is Pain?[edit | edit source]

Many believe pain is a simple sensation that you get after, lets say “closing the car door on your finger”. It’s easy to understand in a structural model of reasoning, which believes that the more pain you get the more tissue damage you are causing. Although it is not as simple as this, and much of the persistent pain that physiotherapists see on a everyday basis would not be adequately addressed by this model of thinking. Recent authors have indicated that pain could be a measure of potential threat rather than an indication of tissue health.[6]

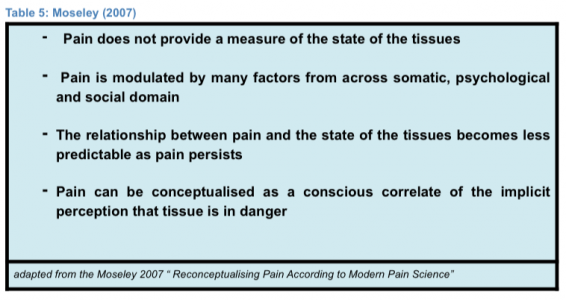

Lorimer Moseley’s 2007 paper “Reconceptualising Pain According to Modern Pain Science” suggests that :[7]

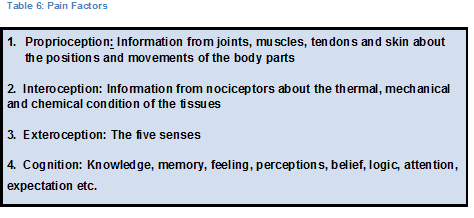

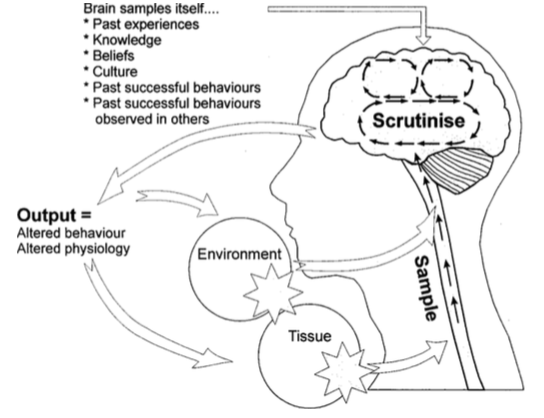

If we look at the work of Louis Gifford and the Mature Organism Model [8](1998) we see that when we get a input nociceptive stimuli the nerve impulse travels to the brain and is sampled against a number of different factors such as:

After the brain scrutinises all these unconscious pieces of information it asks itself, “How dangerous is this really?” Pain is a good thing and tries to protect our tissues, we as physiotherapists need to monitor if pain is adaptive or maladaptive .[9]

Every Chronic Pain Was Once Acute[edit | edit source]

As pain carries on the patient may become more anxious, stressed, helpless, sedentary, further reinforcing the brain’s choice to cause pain.[6],[10]We often see a fire alarm that goes off from a piece of burning toast similarly our bodies alarm system can malfunction in much the same way if the body becomes hypersensitive..

More and more research is starting to look at pain as a disorder rather than a symptom. [11] Just as asthma, diabetes or epileptic patients are educated on the mechanisms of their disease and how their actions could make their condition better or worse. Persistent pain patients should be socratically introduced to their condition by facilitating dialogical critical thinking in a similar manner .[5]

Often it can be easier to address peoples lack of care for their pain when patients have co-morbidities because physiotherapists are able to compare how poorly their pain is being managed. If we take a moment to look at Diabetes and persistent pain through the same lense, and imagine that doctors had a patient coming in every 3 days for an insulin injection and an overnight stay because they weren't managing their diabetes correctly there would be a problem. In a physiotherapy setting if a patient was coming into your clinic every 3 days for some manual therapy to decrease their pain while they otherwise poorly manage their condition, this would not be right. Some therapists are content with that, We shouldn’t be…!

Further reading Louis Gifford (2000) Shopping Basket Approach

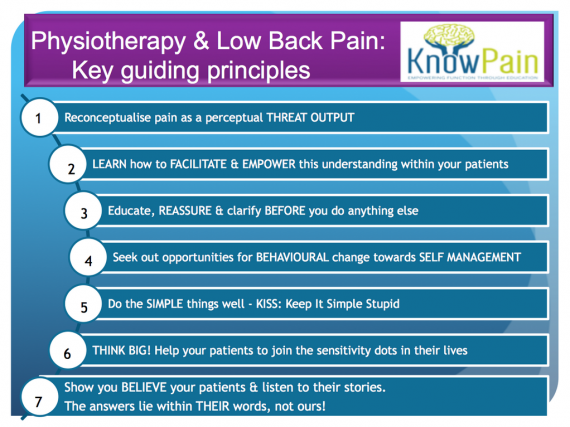

Neuroscience Education[edit | edit source]

According to Louw et al. (2011) Neuroscience education is a cognitive based intervention that aims at reducing pain and maladaptive behaviours by guiding patients to grasp understanding of the mechanisms underpinning their pain experience.[12]

This semi complex information needs to be delivered to the patient in a way that is clear and easy to understand. Language and other communication techniques such as drawings,pictures, videos, workbooks can aid patient learning. Research shows that traditionally clinicians tend to underestimate patients ability to understand complex pain, when in fact patients are very interested in learning about their pain .[12]

Multiple studies have shown that Neuroscience Education combined with graded exercise is in line with the best evidence available for treating persistent pain.[12] Resulting in decreased fear, pain, cognition and physical performance, increased pain thresholds during exercises, and reduced brain activity(especially the amygdala) that is usually involved with pain.[12][13]

Figure from Mike Stewart MCSP SRP PG Cert(Clin Ed): Know Pain http://knowpain.co.uk/

Explaining Pain: How to Do it in Under Ten Minutes[edit | edit source]

Clinical Example: Osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

When explaining a condition such as osteoarthritis to a patient we must consider what their viewpoint of the condition must be. Osteoarthritis is a condition of cartilage degeneration, subchondral bone stiffening and active new bone formation[14].

Osteoarthritis is a complex sensory and emotional experience. An individual’s psychological characteristics and immediate psychological contest in which pain is experienced both influence their perception of pain[15].

Research has utilised qualitative methods and focus groups to establish the patient’s point of view. A common theme that is emerging is that patients are sometimes dissatisfied with the overall level of understanding, help and information that is given to them by healthcare professionals[16]. Patients also expressed concern that there was a lack of understanding by healthcare professionals as to the impact that osteoarthritis can have on an individual’s life[16].

As physiotherapists, we must be aware of current and alternative treatments for OA (hydrotherapy, acupuncture etc) as contradictory information being given to the patient from different sources may lead to confusion as to what exactly they should be doing[16].

Somers et al[17]highlights that patients may adopt certain attitudes towards pain; Patients who are pain catastrophizing tend to focus on and magnify their pain sensations. This group of patients tend to feel helpless in the face of pain. Patients who adopt this stance report higher levels of pain, have higher levels of psychological and physical disability.

The second stance is patients who have pain related fear. They have a fear of physical activity as a result of feeling vulnerable to pain during activity. This group are more likely to engage in avoidance behaviours such as avoiding movement[17].

We as physiotherapists must remember that OA patients with a fear of engaging in painful movements may be hesitant to engage in physical activity. This can contribute to a vicious cycle of a more restricted and a physically inactive lifestyle which will lead to increased pain and disability[17]

Hendry et al[18]conducted qualitative research on primary care patients with OA. They found that personal experience, aetiology of arthritis and motivational factors all influenced compliance rates towards physical activity. Some patients believed that their joint problems were a direct result of heavy physical activity[16]. This is where we as clinicians must be aware that patients may present questions such as;

‘why should we exercise when our knees hurt?’

In the same study patients were asking;

‘if it is wear and tear on the bone, is it helping to do all this exercise, walking and that?’

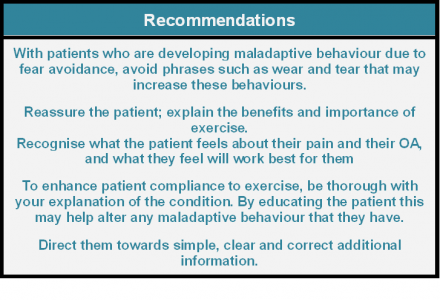

As physiotherapists we must be careful with our choice of words, phrases such as ‘wear and tear’ may be misinterpreted by some patients and lead to further maladaptive behaviour. Grime et al[19]established that an ongoing concern of musculoskeletal professionals is that the use of this ‘wear and tear’ explanation often leads to decreased physical activity to avoid further ‘wearing of the joint’.

A unique approach adopted by a number of patients in the same study by Grime et al[19]was the ‘use it or lose it’ approach. This simply put was use the joint or lose your functional ability. As physiotherapists we could utilise a similar approach to get our patients to comply with the physical exercise that we have prescribed as an intervention. Through effective communication we can increase a patient’s self efficacy and reduce their level of physical disability[15]. Patients with higher self efficacy for pain control had higher thresholds for pain stimuli[15]. Can we as physiotherapists use this to our advantage to increase patient’s compliance to exercise?

Exercise has been shown to have a positive effect on functional ability in patients with OA[14]. We as physiotherapists must consider the role of pain related fear in patients with OA and investigate different treatment approaches to combat this behaviour[14].

Scopaz et al[20]suggests psychological factors such as anxiety, fear and depression may also be related to physical function in patients with OA of the knee.

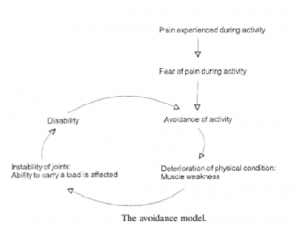

Further to this, a model of fear avoidance suggests that patients can either be adaptive and non-adaptive in their approach to their pain and functional ability[20]

This model indicates that anxiety + fear avoidance beliefs are significant predictors of self report physical function in patients with knee OA[20].

Following on from this, we may also consider the avoidance model presented by Dekker et al[21](right).

This model indicates that a decreased muscle strength as a result of activity avoidance leads to activity limitations[22].

Recommendations[edit | edit source]

'What can us as physiotherapists do to combat these beliefs that may be instilled in patients?'

Table 7 highlights some useful techniques when managing patients with OA.

Further Reading:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Darlow, B., Dowell, A., Baxter, G., Mathieson, F., Perry, M. and Dean, S. (2013). The Enduring Impact of What Clinicians Say to People With Low Back Pain. The Annals of Family Medicine, 11(6), pp.527-534.

- ↑ Croft, P., Macfarlane, G., Papageorgiou, A., Thomas, E. and Silman, A. (1998). Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ, 316(7141), pp.1356-1359.

- ↑ Butler, D. and Moseley, G. (2003). Explain pain. Adelaide: Noigroup Publications.

- ↑ Nair, M. and Peate, I. (2012). Fundamentals of Applied Pathophysiology. Chicester: Wiley.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Yelland, M. (2011). What do patients really want?. International Musculoskeletal Medicine, 33(1), pp.1-2.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Moseley, G. (2003). A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy, 8(3), pp.130-140.

- ↑ Moseley, G. (2007). Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Phys. Ther. Rev., 12(3), pp.169-178.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gifford L (Ed) (1998) Topical Issues in Pain 1: Whiplash – science and management. Fear avoidance beliefs and behaviour. CNS Press Falmouth.

- ↑ Stewart, M. (2014). The Road To Pain Reconceptualisation: Do Metaphors Help Or Hinder The Journey?. Journal of the Physiotherapy Pain Association, Winter(36), pp.24-31.

- ↑ Gifford L S (Ed) (2000) Topical Issues in Pain 2: Biopsychosocial assessment. Relationships and pain. L. S. Gifford. Falmouth, CNS Press

- ↑ Bourke, J. (2014). The story of pain. London Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D. and Puentedura, E. (2011). The Effect of Neuroscience Education on Pain, Disability, Anxiety, and Stress in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(12), pp.2041-2056.

- ↑ Veinante, P., Yalcin, I. and Barrot, M. (2013). The amygdala between sensation and affect: a role in pain. J Mol Psychiatry, 1(1), p.9.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 HEUTS, P.H., VLAEYEN, J.W., ROELOFS, J., DE BIE, R.A., ARETZ, K., VAN WEEL, C. and VAN SCHAYCK, O.C., 2004. Pain-related fear and daily functioning in patients with osteoarthritis. Pain. , vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 228-235.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 HUNTER, D.J., MCDOUGALL, J.J. and KEEFE, F.J., 2009. The symptoms of osteoarthritis and the genesis of pain. Medical Clinics of North America. , vol. 93, no. 1, pp. 83-100.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 HILL, S., DZIEDZIC, K.S. and NIO ONG, B., 2011. Patients' perceptions of the treatment and management of hand osteoarthritis: a focus group enquiry. Disability and Rehabilitation. , vol. 33, no. 19-20, pp. 1866-1872.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 SOMERS, T.J., KEEFE, F.J., PELLS, J.J., DIXON, K.E., WATERS, S.J., RIORDAN, P.A., BLUMENTHAL, J.A., MCKEE, D.C., LACAILLE, L. and TUCKER, J.M., 2009. Pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in osteoarthritis patients: relationships to pain and disability. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. , vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 863-872.

- ↑ HENDRY, M., WILLIAMS, N.H., MARKLAND, D., WILKINSON, C. and MADDISON, P., 2006. Why should we exercise when our knees hurt? A qualitative study of primary care patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Family Practice. Oct, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 558-567.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 GRIME, J., RICHARDSON, J.C. and ONG, B.N., 2010. Perceptions of joint pain and feeling well in older people who reported being healthy: a qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice. , vol. 60, no. 577, pp. 597-603.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 SCOPAZ, K.A., PIVA, S.R., WISNIEWSKI, S. and FITZGERALD, G.K., 2009. Relationships of fear, anxiety, and depression with physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. , vol. 90, no. 11, pp. 1866-1873.

- ↑ DEKKER, J., TOLA, P., AUFDEMKAMPE, G. and WINCKERS, M., 1993. Negative affect, pain and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the mediating role of muscle weakness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. , vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 203-206.

- ↑ HOLLA, J.F., VAN DER LEEDEN, M., KNOL, D.L., PETER, W.F., ROORDA, L.D., LEMS, W.F., WESSELING, J., STEULTJENS, M.P. and DEKKER, J., 2012. Avoidance of activities in early symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: results from the CHECK cohort. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. , vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 33-42.