Overview of Dysphagia

Original Editor - Ewa Jaraczewska based on the course by Srishti Banerjee

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Dysphagia affects an individual's ability to safely and effectively eat and drink. One in six adults report difficulty swallowing, but only half discuss their symptoms with a clinician.[1] Consequences of dysphagia include malnutrition, dehydration, an increased risk of aspiration pneumonia and death from choking. Dysphagia also has a significant impact on social and psychological well-being, as eating and drinking are important social activities.

By understanding dysphagia, healthcare professionals can help to ensure early detection, enhanced management, reduced length of hospital stays, improved rehabilitation outcomes, and decreased morbidity and mortality. This article offers a detailed description of oropharyngeal and oesophageal dysphagia.

General Definition of Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

Dysphagia is defined as difficulty swallowing liquids, food or medication, which can occur during the oropharyngeal or oesophageal phases of swallowing.[2]

Epidemiology of Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

20% of the general population have dysphagia. This number increases to 50-66% of people aged over 60 years. More women are affected than men.[3]

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

"Oropharyngeal dysphagia is characterised by the inability to initiate the swallowing process."[4]

"Oropharyngeal dysphagia is a clinical symptom, defined by the difficulty to move the alimentary bolus from the mouth to the oesophagus."[5]

Oropharyngeal dysphagia (or transfer dysphagia) can lead to:[6]

- malnutrition and / or dehydration caused by a decrease in deglutition (or swallowing) efficacy:

- pneumonia with associated mortality caused by a reduced ability to swallow safely and the development of airway obstruction with choking:

- Banda et al.[9] found that post-stroke dysphagia increases the risk of pneumonia almost 4.5 times

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is associated with structural alterations of the oral cavity and the pharynx.[4] It can also be caused by functional swallowing disorders.[2]

Structural alterations affect bolus progression. The following structural abnormalities can lead to oropharyngeal dysphagia:

- oesophageal and ENT tumours

- neck osteophytes

- post-surgical oesophageal stenosis

- complications following head and neck cancer

The normal swallow response in healthy individuals ranges from 0.6–1 s.[10] Functional disorders of swallowing affect the oropharyngeal swallow response. These disorders can be caused by:

- ageing

- stroke

- systemic or neurological diseases

Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

Symptoms of dysphagia are often ignored by patients or caregivers and not reported to physicians.[2] However, the percentage of individuals with oropharyngeal dysphagia is high. It's important to note that prevalence rates vary depending on the screening method and the population tested. For instance, the highest rates are found on the African continent (64.2%) and the lowest rates in Australia (7.3%).[2]

Rofes et al. report the following prevalence rates for oropharyngeal dysphagia:[11]

- over 30% of patients with cerebrovascular accident

- 52-82% of patients with Parkinson’s

- 84% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease

- up to 40% of adults aged 65 years or more (prevalence increases with increasing age)

- more than 60% of elderly institutionalised patients

Takizawa et al. report the following prevalence rates for oropharyngeal dysphagia, with a wider range in individuals with stroke and Parkinson's:[12]

- 8.1-80% of patients with stroke

- 11–81% of individuals with Parkinson’s

- 27–30% of individuals with traumatic brain injury

- 91.7% of individuals with community-acquired pneumonia

According to Rajati et al.,[13] there is a high prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in the paediatric population. These high rates might be caused by:[13]

- dental issues / abnormalities

- large tongue and tonsils

- craniofacial abnormalities (i.e. problems with the cranial bones and structures of the mouth and throat that develop prenatally)

- prenatal issues with the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. oesophageal atresia)

- tracheoesophageal fistula caused by prolonged ventilator support (e.g. in preterm infants)

- vocal cord paralysis

- tracheostomy surgery

- oesophageal stimulation or ulceration caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease

Mechanisms of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

Velopharyngeal incompetence occurs when "the velum and lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls fail to separate the oral cavity from the nasal cavity during speech and deglutination."[14] It can be caused by:[11]

- impairment of the vagus nerve and pharyngeal plexus due to neurological and neurosurgical conditions

- brainstem stroke

- decompression of the foramen magnum

- treatments for head and neck cancer that cause intentional or unintentional "sacrifice" of the nerve supply to the palatal muscles[15]

- oropharynx tumours

- radiotherapy to the nasopharynx

Absent, inefficient, or infrequent laryngeal elevation occurs when the thyrohyoid and suprahyoid muscles are unable to assist with the anterior and superior movement of the hyolaryngeal complex. Because of this, the cricopharynx does not relax. This pathology can arise from the following neurological and neurosurgical conditions:[15]

- posterior circulatory stroke

- cerebellopontine angle surgery

- high-level spinal cord injuries

- tumours

- extensive surgery for head and neck cancer

Inappropriate or inefficient laryngeal closure results in "suboptimal laryngeal protection and diversion of the food bolus". It can be caused by:[15]

- partial or complete resection of the epiglottis

- high vagal injury which involves the superior laryngeal nerves

- brainstem lesions

- brainstem surgery

Inefficient thyropharyngeal contraction leads to the stasis (slowing or stoppage) of a food bolus in the pyriform fossa on the affected side. This can be caused by:[15]

- issues with cranial nerves IX, X, and XI (often associated with stroke or neurosurgery)

Cricopharyngeal dysmotility: cricopharyngeus must relax at the correct time to enable a successful swallowing. Cricopharyngeal dysmotility can have primary and secondary causes:[15]

- primary: caused by neurological control issues

- secondary: occurs when there is a lack of elevation of the larynx

Idiopathic spasm of the cricopharyngeal: there is a simultaneous contraction of the thyropharyngeus and cricopharyngeus muscles. This can cause Zenker’s diverticulum to develop (also known as pharyngeal pouch).[15]

Clinical Presentation of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

The following signs and symptoms can occur with oropharyngeal dysphagia:[15][4]

- nasal regurgitation: often associated with velopharyngeal incompetence and occasionally with cricopharyngeal dysfunction

- multiple attempts to swallow: consistent with laryngeal elevation or cricopharyngeal dysmotility

- coughing immediately after swallowing: may indicate unilateral or bilateral laryngeal incompetence

- delayed cough: can suggest hypopharyngeal dysfunction

- hoarseness, breathing difficulties, and dysarthria

Oesophageal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

"Oesophageal dysphagia is characterised by difficulty transporting food down the oesophagus."[4]

Oesophageal dysphagia is associated with mechanical (structural ) problems or motor disorders. Mechanical (structural) disorders occur when there is a barrier that obstructs the flow of a bolus. It can be suspected when an individual has difficulty swallowing solids.[16] Mechanical disorders can be intrinsic or extrinsic.[16]

Intrinsic mechanical disorders can include:[16]

- carcinoma

- benign tumours

- diverticulum (small pouch inside the oesophagus)

- eosinophilic oesophagitis (inflammation of the oesophagus)

- peptic stricture (narrowing or tightening of the oesophagus)

- oesophageal rings and webs

- schatzski ring (narrowing of the lower oesophagus)

- foreign body

- pill-induced stricture (e.g., alendronate, potassium chloride tablets)

- strictures associated with tracheoesophageal fistula / its treatment

Extrinsic mechanical disorders can include:[16]

- mediastinal mass

- vascular compression

- spinal osteophyte

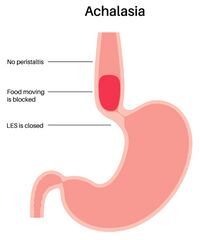

Motility (motor) disorders result in peristaltic failure.[4] These disorders can lead to problems with both solid and liquid boluses. However, difficulties swallowing solids occur more frequently.[16] Motility disorders can be divided into primary or secondary disorders.[16]

Primary motility disorders can include:[16]

- achalasia (the absence of peristalsis with failure of the lower oesophagal sphincter to relax)

- distal oesophageal spasm

- hypercontractile oesophagus (i.e. jackhammer oesophagus)

- hypertensive lower oesophageal sphincter / gastroesophageal junction outflow obstruction

- other peristaltic abnormalities

Secondary motility disorders can include:[16]

- Chagas disease (a disease caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi[17])

- reflux-related dysmotility

- systemic sclerosis and other rheumatologic disorders

- medications, such as anticholinergics, antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Prevalence of Oesophageal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of oesophageal dysphagia increases with age and specific comorbidities. For instance, around 30.9% of individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease, around 8% of individuals with eosinophilic oesophagitis (EOE) and around 4.5% of those with oesophageal stricture experience oesophageal dysphagia.[18] There are also region-specific differences. Australia reports a prevalence of 16%, Argentina 13%, the United States 7.8%, and China only 1.7%.[18]

Clinical Presentation of Oesophageal Dysphagia[edit | edit source]

Oesophageal dysphagia may have different clinical features depending on the cause of dysphagia.

Primary motility disorders:[19]

- dysphagia with liquids as the predominant symptom may indicate neuromuscular motility disorders

- significant, progressive dysphagia with both liquids and solids, which can be relieved by swallowing repeatedly, Valsalva manoeuvres, or positional changes, is associated with achalasia. Additional symptoms include regurgitation of undigested food, particularly at night, coughing, heartburn, weight loss, and aspiration

- intermittent, non-progressive dysphagia without weight loss where the patient also reports globus sensation (i.e. the feeling of having a lump in the throat), regurgitation, and heartburn are consistent with a diffuse oesophageal spasm

Secondary motility disorders:[19]

- regurgitation and heartburn affect 60% of patients with scleroderma

Obstructive intrinsic structural lesions:[19]

- intermittent non-progressive dysphagia for only solid food indicates that an obstructive lesion may be present, such as an oesophageal ring or web

- “steakhouse syndrome” is a term for Schatzki connective tissue B ring symptoms. Symptoms tend to occur after eating bread and meat, especially when the food is eaten quickly. "Meat or food impaction with prolonged inability to pass an ingested bolus (even with ingestion of liquid) is typical of obstructive intrinsic structural lesions."[19]

Extrinsic diseases:[19]

- progressive dysphagia, heartburn, odynophagia (pain when swallowing), food impaction, weight loss, and chest pain imply a narrowing of the oesophageal lumen through inflammation, neoplasm, or fibrosis

- oropharyngeal ulcerations, oedema, and erythaema with coughing, crying, vomiting, drooling, and varying degrees of respiratory distress and stridor are associated with thermal or chemical burns to the oesophagus

- dysphagia for solids and then liquids that progressively develops over weeks to months often occurs in oesophageal carcinoma

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Philipsen BB. Dysphagia - pathophysiology of swallowing dysfunction, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. J Otolaryngol Rhinol. 2019;5:063.

- Dziewas R, Allescher HD, Aroyo I, Bartolome G, Beilenhoff U, Bohlender J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of neurogenic dysphagia - S1 guideline of the German Society of Neurology. Neurol Res Pract. 2021 May 4;3(1):23.

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Dysphagia Resources for Patients

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Adkins C, Takakura W, Spiegel BMR, Lu M, Vera-Llonch M, Williams J, Almario CV. Prevalence and Characteristics of Dysphagia Based on a Population-Based Survey. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Aug;18(9):1970-1979.e2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Thiyagalingam S, Kulinski AE, Thorsteinsdottir B, Shindelar KL, Takahashi PY. Dysphagia in older adults. InMayo clinic proceedings 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 96, No. 2, pp. 488-497). Elsevier.

- ↑ Chilukuri P, Odufalu F, Hachem C. Dysphagia. Mo Med. 2018 May-Jun;115(3):206-210.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Banerjee S. Overview of Dysphagia Course. Plus, 2024.

- ↑ Verin E, Clavé P, Bonsignore MR, Marie JP, Bertolus C, Similowski T, Laveneziana P. Oropharyngeal dysphagia: when swallowing disorders meet respiratory diseases. Eur Respir J. 2017 Apr 12;49(4):1602530.

- ↑ Clavé P, Terré R, De Kraa M, Serra M. Approaching oropharyngeal dysphagia. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2004 Feb 1;96(2):119-31.

- ↑ Vivanti AP, Campbell KL, Suter MS, Hannan-Jones MT, Hulcombe JA. Contribution of thickened drinks, food and enteral and parenteral fluids to fluid intake in hospitalised patients with dysphagia. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009 Apr;22(2):148-55.

- ↑ Reber E, Gomes F, Dähn IA, Vasiloglou MF, Stanga Z. Management of Dehydration in Patients Suffering Swallowing Difficulties. J Clin Med. 2019 Nov 8;8(11):1923.

- ↑ Banda KJ, Chu H, Kang XL, Liu D, Pien LC, Jen HJ, Hsiao SS, Chou KR. Prevalence of dysphagia and risk of pneumonia and mortality in acute stroke patients: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022 May 13;22(1):420.

- ↑ Steele CM, Peladeau-Pigeon M, Barbon CAE, Guida BT, Namasivayam-MacDonald AM, Nascimento WV, Smaoui S, Tapson MS, Valenzano TJ, Waito AA, Wolkin TS. Reference Values for Healthy Swallowing Across the Range From Thin to Extremely Thick Liquids. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019 May 21;62(5):1338-1363.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rofes L, Arreola V, Almirall J, Cabré M, Campins L, García-Peris P, Speyer R, Clavé P. Diagnosis and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia and its nutritional and respiratory complications in the elderly. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2011;2011(1):818979.

- ↑ Akizawa C, Gemmell E, Kenworthy J, Speyer R. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Stroke, Parkinson's Disease, Alzheimer's Disease, Head Injury, and Pneumonia. Dysphagia. 2016 Jun;31(3):434-41.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rajati F, Ahmadi N, Naghibzadeh ZA, Kazeminia M. The global prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Transl Med. 2022 Apr 11;20(1):175.

- ↑ Johns DF, Rohrich RJ, Awada M. Velopharyngeal incompetence: a guide for clinical evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Dec;112(7):1890-7.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Menon JR. Pharyngeal Dysphagia. Int J Head Neck Surg 2022;13(1):55-61.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 Selvanderan S, Wong S, Holloway R, Kuo P. Dysphagia: clinical evaluation and management. Internal Medicine Journal. 2021 Jul;51(7):1021-7.

- ↑ Lidani KCF, Andrade FA, Bavia L, Damasceno FS, Beltrame MH, Messias-Reason IJ, Sandri TL. Chagas Disease: From Discovery to a Worldwide Health Problem. Front Public Health. 2019 Jul 2;7:166.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Mittal RK, Zifan A. Why so Many Patients With Dysphagia Have Normal Esophageal Function Testing. Gastro Hep Adv. 2024;3(1):109-121

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Kruger D. Assessing esophageal dysphagia. JAAPA 2014;27(5):23-30.