Burn Wound Healing Considerations and Recovery Care Interventions

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (18/04/2024)

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Please see this document for a growing list of wound care terminology and definitions.

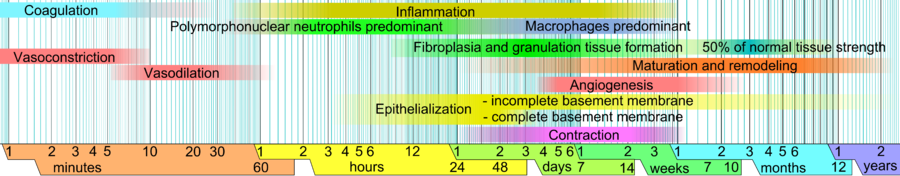

It has been well documented throughout wound journals that wound “healing” does not stop when re-epithelialization has been accomplished. The remodeling and strengthening of the skin and underlying tissue, and maturation of the scar that results from deeper burn wounds, continues for months to years after visible closing has occurred. Care of the skin and soft tissue during the remodeling phase is of paramount importance to ensure the best possible outcome- both cosmetically and functionally.

Unfortunately, there is very little documented, either evidence-based or in case reports, to describe the best care for burn wounds that are not managed surgically but are allowed to close secondarily. This mainly includes those burn wounds that are expected to re-epithelialize within 3 weeks - the superficial partial thickness burn wound for the most part as well as the partial thickness burn wounds that are allowed to re-epithelialize before any deeper burn wounds may be considered for grafting.

Burn Wound Healing Physiology[edit | edit source]

Epithelialisation[edit | edit source]

"Epithelialization is a process of covering defect on the epithelial surface during the proliferative phase that occurs during the hours after injury. In this process, keratinocytes renew continuously and migrate upward from the basal to the differentiated layers. A continuous regeneration throughout homeostasis and when skin injury occurs is maintained by the epidermal stem cells ... Epithelialization is the most essential part to immediately reconstruct skin barrier in wound healing where keratinocytes undergo a series of migration, proliferation and differentiation."[1]

Superficial partial thickness wounds:

- Epithelialisation occurs as the proliferative phase comes to an end and the remodeling phase begins

- Significant decrease in the amount of exudate released from the wound

- Risk of infection decreases

- Initial epithelial resurfacing is a thin, single layer of keratinocytes which will mature to a stratified, multi-cell layered structure that provides the barrier functions of the skin

- Skin appendages (hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands) eventually return to normal functioning

- No granulation tissue is generated and therefore these burn wounds generally heal without scar formation

Burn injuries of indeterminate depth or deep partial thickness wounds:

- Involves damage deeper into the dermal layer and may destroy many of the skin appendages.

- Full thickness burns eliminate all of the dermal appendages.

- Healing of these burn injuries involve scar formation which never regains the normal structure and function of the skin, this is also true for areas of skin graft placement.

Burn Wound Care During Re-epithelialisation[edit | edit source]

"Care of the burn wound as it is re-epithelializing is critical to allow the new epidermis to resurface the burn and mature. Any trauma or changes in the wound environment may delay or prevent ongoing epithelialization or cause deterioration of new epithelium." -Diane Merwarth, Physical Therapist, Wound Care Specialist[2]

Wound Cleansing[edit | edit source]

- must be extremely gentle to avoid traumatising the new epithelium, a gentle rinsing and patting of the wound is sufficient

Dressing Selection and Techniques[edit | edit source]

- use of nonadherent dressings that minimize evaporative water loss while not causing a situation where the wound may be too wet.

- decreasing dressing change frequency minimises the risk of causing trauma to the fragile new epithelium

- ideally dressing changes should be undertaken every 3-5 days, depending on the dressing being used, unless there are infection concerns

- discontinue the use of silver-based dressings also facilitates the final re-surfacing of the burn wound

- protection of the wound margins, including the new epidermis, will help keep dressings from adhering and avoid potential periwound maceration

- dressing application should be discontinued when there is no drainage on the dressings and the wound area is visibly re-epithelialised

Clinical Pearl: how to handle adherent dressings to wound burn surfaces [edit | edit source]

- Do not force old dressing removal

- Trim any loose dressing and leave the adherent area intact

- Re-bandage the entire area and attempt removal at the next change

- If it is imperative that the dressing be removed, apply a thick layer of Vaseline or silver sulfadiazine and attempt removal in 24 hours

| Benefits | Risks | |

|---|---|---|

| petrolatum-based gauze dressing

(eg Xeroform or Vaseline gauze) |

|

|

| Non-adherent Foam dressing |

|

|

| Hydrocolloids |

|

May maintain too moist wound environment |

| Transparent Films | Allows for visual monitoring of wound |

|

| Alginate dressings |

|

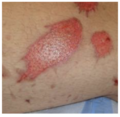

Burn Wound Complication: Maceration[edit | edit source]

Maceration is a common complication of burn wounds. Prolonged exposure to excessive moisture effects periwound skin and causes it to be weakened and easily ruptured, due to:[3][4]

- decreased elasticity and increasing brittleness of the epidermis

- decreased collagen density

- flattening of the basement membrane

- decreased binding of the basement membrane to the extra-cellular matrix

- impaired re-epithelialisation

All photos provided by and used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Prevention is the best intervention to avoid the complications associated with maceration:

- Appropriate dressing selection to manage drainage

- Appropriate dressing change frequency

- Protecting the periwound skin and any epithelial islands within the wound:

- applying an ointment, paste, emulsifier or liquid polymer to protect the skin from moisture exposure. Example: zinc oxide paste, petrolatum or antibiotic ointment

- placing a dressing or dry gause between the digits or skin folds

Clinical Pearl: Zinc Oxide Paste[edit | edit source]

It is quite adherent to the skin and does not need to be completely removed at each dressing change. The area can be gently wiped to remove the surface residue and crusted exudate. If there is still adequate paste on the skin, it is not necessary to add more paste. If there are areas of sparse coverage, more paste can be added. When protection of the skin is no longer indicated, any resistant paste can be removed by applying a layer of petrolatum and wiping the skin after a few minutes.

Post-healing Skin Care[edit | edit source]

After the skin has re-epithelialised, care of the new epithelium must be diligent.

- Moisture retention and hydration

- It can take up to 1 year post re-epithelialization for these functions to be restored following superficial partial thickness burn injuries

- During the remodeling phase, hydrating creams or lotions can replace some of the moisture retention functions of the skin

- General recommendations for moisturizing and or hydrating skin include using a non-irritating fragrance-free cream or lotion specific for moisturising the skin

- Avoid exposure to ultraviolet rays

- Increased the risk of developing skin cancer

- Recommendations for protection from the sun include use of sun screen of at least 50 SPF, and wearing clothing or hat to cover the newly-healed skin

- Decrease friction on new skin

- Bathing: avoid aggressive scrubbing of the new skin while washing and drying

- Application of moisturizers: done with minimal friction. It is not necessary to completely rub the cream or lotion into the skin as it will be absorbed very quickly into the dry skin.

- Clothing selection:

- Avoid any tight clothing over area of burn wound

- Avoid wearing any clothing made of rough fabric

- Recommend well fitting shoes

- Recommendations typically include loose, soft clothing. Socks should always be worn with shoes.

- Activity and nutrition

- A burn injury results in a persistent hyper-metabolic state which requires sufficient caloric intake to support metabolism. Recommendation for a dietician or nutritionist consultation.

- Fatigue is a common side effect of the energy requirements of this hypermetabolic state

Post Burn Wound Injury Care and Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Physical Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

- Maintaining range of motion (ROM), especially when elasticity of skin around the joint may be impaired by scar formation

- ROM and functional activities can effect a burn survivor's long-term outcomes

- Initial gait training using a treadmill for patients with lower limb burn injuries has a positive outcome on later gait abilities over land

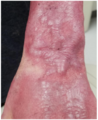

Burn Scar Management[edit | edit source]

"Hypertrophic scar formation is a significant debilitating factor following a burn injury. For burn survivors who suffer deep-partial or full thickness injuries, development of hypertrophic scars is inevitable. Damaged or destroyed extracellular matrix is unable to regenerate, and therefore can’t provide the components needed to regenerate the epithelium. The excessive and prolonged inflammatory response that is normal to burn injuries results in the production of immature collagen." - Diane Merwarth, Physical Therapist, Wound Care Specialist[2]

Hypertrophic scar characteristics generally include:[5]

- elevated, firm , and erythematous in appearance

- pruritic (itchy) and tender for the patient

- limited to the site of the original burn wound injury

- grow in size by pushing out the scar margins

Additionally, because the epidermis is not regenerated, the normal functions of the skin are not restored:[2]

- loss of sweat glands, which diminishes thermoregulation in the involved area

- sebaceous glands are not available to provide lubrication to the skin and hair follicles

- pliability/elasticity of the skin and soft tissue is severely diminished which directly contributes to scar contracture and limited functional ROM

- can be considered aesthetically unappealing by burn survivors

- coverage with a skin graft can mitigate some of the complications of hypertrophic scars

All photos provided by and used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Hypertrophic Scar Noninvasive Management[edit | edit source]

Hypertrophic scars are a dominant type of pathological scar formation after burns. Nowadays, hypertrophic scarring is described as “the greatest unmet challenge after burn injury.”[5]

A 2023 report determined that there is no consensus for any single intervention in management of hypertrophic scars.

- Silicone Gel.

- Silicone gel (pieces of thin, flexible medical grade silicone, can come in a sheet or as a self-drying gel) can be placed over hypertrophic scars. These products may decrease post-burn pruritis and dryness.[6]

- They can be used alone or underneath pressure garments, splints, or casts.[6]Scar quality improvements may be more significant when silicone use is combined with pressure garment therapy (see below for more information).[7]

- Despite a lack of strong evidence, many burn care algorithms and protocols include silicone as the first or primary therapy in scar management[2]

- The American Burn Association states there are "no clear benefits to using gels versus gel sheets or nonsilicone versus silicone products with respect to the treatment effect, but there appear to be fewer adverse reactions when using silicone gels compared to gel sheets."[8]

- Some patients may have an allergy or sensitivity to silicone, therefore skin checks should be performed frequently[6]

- Massage therapy was found in recent studies to provide significant short-term improvement on burn scars, but no long-term benefit was appreciated. Massage was also found (in a 2017 report) to decrease pruritis, but no evidence was found on lasting effect on scar height or thickness with massage. Some studies on scar management were specific to hands, first stating that prevention is the best intervention for positive outcomes. It determined that early initiation of compression to decrease edema, aggressive ROM with stretching, and the use of splints were effective in improving outcomes for burn survivors with hand burns. It also reported that any joints that started developing contractures benefitted from use of K-wires.

- Pressure garment therapy (PGT) has been extensively studied for management of burn scars. An animal study in 2015 reported that effectiveness of PGT is directly related to the anatomical location of the scar. It also found that contractile strength and scar contracture was significantly improved with PGT versus scars not treated with PGT. Although the mechanism of action of pressure garments is not fully understood, it is theorized that the mechanical forces applied by the pressure garments decreases the scar contracture and helps to organize the deposition of collagen during the remodeling phase.

Multiple studies are contradictory or provide inconsistent results. Some show evidence of positive outcomes with PGT when the garments are worn 24/7 (being removed only for bathing) versus when the garments are worn for less time. Some reports show the ideal pressure exerted by garments is 15-25 mmHg, although pressure under garments is not routinely measured. Other studies recommend a pressure that equals or exceeds capillary closing pressure, which can be 40 mmHg in some areas. There are consistent reports that garment fatigue significantly decreases the effectiveness of PGT. In all studies involving human subjects, outcomes are directly affected by poor patient adherence. Reasons reported for poor adherence include

- Garments are uncomfortable

- Garments can be too hot

- They are difficult to don and doff

- Cost is a significant deterrent to obtaining garments, as well as in replacement garments when garment fatigue becomes a factor

Effectiveness of PGT on burn scars is not well supported in some cases. Some studies report significant improvement in scars with PGT using a pressure of 15-25 mmHg, but the studies included in this report had a weak level of evidence with no studies looking at long-term results following PGT. Yet another report demonstrated good evidence in both prophylactic and curative interventions with PGT. If the PGT is initiated within 2 months of injury, with a pressure of 20-25 mmHg for at least 12 months, there was improvement in scar color, thickness, pain reduction and scar quality (as assessed with a validated scar assessment scale).

Other interventions in management of burn hypertrophic scars have also been investigated. In 2023, a study looking at use of corticoid-embedded dissolving microneedles was studied. It found an effective delivery method in using a hyaluronic acid dressing onto which the microneedles are implanted. After applying this dressing to a burn scar, the microneedles penetrate the epidermis with minimal to no pain and can travel into the dermis. As the microneedles dissolve, they release the embedded corticosteroid, which has been found to be effective in reducing the thickness of hypertrophic scars. This intervention holds great promise as being superior to intralesional steroid injections, which can be extremely painful and have a limited area of effectiveness.

Serial casting has also been studied. A small study in 2023 found recovery of full ROM could be achieved with as little as 1 cast change. This study included different frequency of cast changes (1, 3 and 5 times per week), but the ultimate outcome was full ROM with serial casting. This protocol included therapeutic interventions to the joint at each cast change:

- Moist heat

- AROM with end-range stretching

- Joint glides

- Progressive resistive exercises

Once full ROM is achieved, a night-time splint was used to maintain ROM.

In 2022, a study was undertaken comparing Silicone, intra-lesional injections and laser therapy. It found that all were effective in the treatment of burn scars when assessing the scars using the Vancouver Scar Scale. It found that silicone used in combination with intra-lesional injection was superior to either intervention alone. It also reported significant efficacy in using topical silicone in the treatment of hypertrophic burn scars.

Hypertrophic Scar Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

If functional limitation or aesthetic concerns continue after maturation, surgery can be considered.

- Scar contracture release

- Scar debulking

- Cosmetic surgery

There is abundant research and case reports studying various interventions intended to improve outcomes related to hypertrophic scars. Unfortunately the outcomes of these studies and reports are widely variable.

Burn Wound Injury Special Concern: Pruritis[edit | edit source]

Pruritis, or itching, is a significant complication of burn injuries. It is first important to determine if there are underlying factors that may be contributing to the itching. It may be related to an allergy or sensitivity to drug therapy – either topical or systemic. The burn survivor may have an underlying dermatological disorder, or may be developing a neuropathy. If any of these factors are identified, treatment can be targeted to reduce pruritis.

However, if pruritis is directly related to the burn injury, the mechanism for this is not well understood. Therefore, successful treatment has been difficult to discover and no consensus has been reached supporting any single intervention or combination of interventions, and no consistent algorithms have been found to support a given intervention.

Treatments reported to show some success include:

- Topical treatment with creams, lotions or emollients to restore the barrier function

- Systemic treatments, some with moderate results

- Antihistamines

- Gabapentin

- Gabapentin in combination with Pregabalin

- This combination was found superior to either used singly

- Antidepressents

- Somewhat effective for patients with pruritis who also suffer from depression or anxiety

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy

- Physical treatment: found to be effective during the course of therapy, but no long-term benefits were noted

- Compression

- Massage

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clincial Resources:[edit | edit source]

- Practice Guidelines for the Application of Nonsilicone or Silicone Gels and Gel Sheets After Burn Injury (American Burn Association, 2015)

- compression guidelines

- massage guideline

- serial casting

- pressure garment therapy

- patient/caregiver education: education of the patient and/or care giver is important to care for the skin and to care for any wounds that may develop (blisters, skin tears, etc) as the new epidermis matures.

- Education for energy conservation and therapy to facilitate regaining endurance and strength will improve outcomes.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Tan ST, Dosan R. Lessons from epithelialization: the reason behind moist wound environment. The Open Dermatology Journal. 2019 Jul 31;13(1).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Merwarth, D. Management of Burn Wounds Programme. Burn Wound Healing and Recovery Care Course. Plus, 2024.

- ↑ Dhandapani N, Samuelsson K, Sköld M, Zohrevand K, German GK. Mechanical, compositional, and microstructural changes caused by human skin maceration. Extreme Mechanics Letters. 2020 Nov 1;41:101017.

- ↑ Ter Horst B, Chouhan G, Moiemen NS, Grover LM. Advances in keratinocyte delivery in burn wound care. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2018 Jan 1;123:18-32.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 van Baar ME. Epidemiology of scars and their consequences: burn scars. Textbook on Scar Management: State of the Art Management and Emerging Technologies. 2020:37-43.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center. Scar Management After Burn Injury. Available from: https://msktc.org/burn/factsheets/scar-management-after-burn-injury (last accessed 18/April/2024).

- ↑ Pruksapong C, Burusapat C, Hongkarnjanakul N. Efficacy of silicone gel versus silicone gel sheet in hypertrophic scar prevention of deep hand burn patients with skin graft: a prospective randomized controlled trial and systematic review. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery–Global Open. 2020 Oct 1;8(10):e3190.

- ↑ Nedelec B, Carter A, Forbes L, Hsu SC, McMahon M, Parry I, Ryan CM, Serghiou MA, Schneider JC, Sharp PA, de Oliveira A. Practice guidelines for the application of nonsilicone or silicone gels and gel sheets after burn injury. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2015 May 1;36(3):345-74.