Cervical Myelopathy

Original Editor - Bridgit A Finley.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

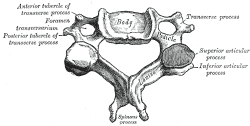

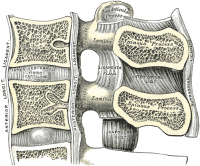

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

Chronic cervical degeneration is the most common cause of progressive spinal cord and nerve root compression. Spondylotic changes can result in stenosis of the spinal canal, lateral recess, and foramina. Spinal canal stenosis can lead to myelopathy, whereas the latter two can lead to radiculopathy.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

[edit | edit source]

The onset is insidious and gradual, which is related to degenerative changes in the cervical spine anatomy. Osteophytic overgrowth, thickening of the ligamentum flavum (dorsally) and of the posterior longitudinal ligament can compress the spinal cord. The intervertebral discs dry out resulting in loss of disc height, which increases compression of the vertebral end plates and osteophytic spurs develop at the margins of the end plates. The degenerative changes encroach on the spinal cord and cause compression.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy can cause a variety of signs and symptoms. The onset is insidious, which typically becomes apparent in persons aged 50-60 years. About half of patients with cervical myelopathy have pain in their neck, scapular area, or arms. Most have symptoms of arm and leg dysfunction. Arm symptoms may include weakness, numbness (nonspecific/dermatomal) or clumsiness in the hands. Leg symptoms may include weakness, difficulty walking, and/or frequent falls. In later cases, bladder and bowel incontinence can occur. The first signs are often increased knee and ankle reflexes. A myelopathy is an upper motor neuron lesion and the patients may present with spasticity, hyperreflexia, clonus, Babinski and Hoffman's sign.

Sex Both sexes are affected equally. Cervical spondylosis usually starts earlier in men (50 years) than in women (60 years).

Age 40-60 years old. Radiologic spondylotic changes increase with patient age; 70% of asymptomatic persons older than 70 years have some form of degenerative change in the cervical spine.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of cervical myelopathy is based on presenting symptoms and physical examination. Plain radiographs alone are of little use as an initial diagnostic procedure. MRI of the cervical spine can identify spinal canal stenosis, as well as rule out spinal cord tumors. Radiographic cervical spinal cord compression and hyperintense T2 intraparenchymal signal abnormalities (MRI) correlate well with the presence of myelopathic findings on physical examination[1].

Neck Disability Index[edit | edit source]

Management / Interventions

[edit | edit source]

Patients with cervical myelopathy that are treated with a conservative approach (anti-inflammatory medications, collar immobilization and physical therapy) may have some short term benefit in relief of painful symptoms. Because the condition is degenerative and progressive, slow and continued progressive neurologic deterioration will occur.

The cord compression is thought to be a combination of static compression and intermittent dynamic compression from cervical motion (flexion/extension).

There is no consensus about the treatment of mild and moderate forms of cervical myelopathy(The Japanese Orthopaedic Association developed a scoring system for cervical myelopathy)[2]. Surgical treatment has no better results than conservative treatment over 2 years of follow-up[3]. Motor training programmes may improve arm and hand functioning at function and/or activity level in cervical spinal cord injured patients[4]. Surgery is needed in severe forms of progressive cervical myelopathy[5][6]. Physiotherapy has an important role before and after the surgery. In the pre-operative phase the physiotherapist will inform about the patients history and about the activity of daily living. The physiotherapist will inform the patient about the treatment and the expectations after the surgery. There are different tests to have an objective view on the abilities of the patient: distance of walking, Neck Pain and Disability Scale,neck disability index and lungfunction.

Exercises to improve the mobility and the proprioception will be given to the patient. The patient starts unencumbered stabilisation exercises and then evolves to more active mobilisation exercises. During the day the patient is stimulated and helped to do daily life activities. The second day the intensity of the exercises increases and then evolve to standing and walking exercises. After a normal rehabilitationprogress the patient can go home after nine day. At home the physiotherapy continues with active exercises. The physiotherapist has to make sure that the patient can continue his activity of daily living(ADL) and increases the intensity of it every day. After a normal rehabilitation there are no limitations to the adl-activities of the patient. Also important in the rehabilitation is to improve the posture[7]. Physiotherapy is important before the surgery to inform the patient and for the physiotherapist to get to know the patient and to set up a rehabilitation program. The main goal is to make the patient able to participate in society again without permanent restrictions due to the surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Special Tests: (+) Clonus, (+) Hoffman's Sign

(+) Lhermitte's Sign - flexion of the cervical spine may cause an "electric shock" sensation down the center of the back.

Common Symptoms

Distal weakness, decreased ROM in the cervical spine, especially extension.

Clumsy or weak hands/ Loss of Dexterity

Pain in shoulder or arms

Unsteady gait/ Clumsy during Walking

Increased reflexes in the lower extremities and in the upper extremities below the level of the lesion.

MRI may be useful to diagnose myelopathy. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) may help rule out peripheral neuropathy.

| [8] | [9] |

| [10] | [11] |

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

Special Tests for Cervical Myelopathy

Differential Diagnosis: Cervical Myelopathy

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Dr. Pablo Pazmino, MD on Cervical Myelopathy

Mayo Clinic information on Spinal Stenosis

Wikipedia on Spinal Stenosis

In this video, Dr. Jeffrey Wang, a professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery of UCLA, reviews Spinal Stenosis

| [12] |

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

57 Year-old male diagnosed with Cervical Myelopathy

Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy in a Patient Presenting With Low Back Pain

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=10SuWQ8ymABjulX7yzOMA4mM0Ok422wmPAwrVWPUMJAoZUZ9gK|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSSReferences[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008;38(12):798.

J Ortho Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(11):701-712.

J Ortho Sports Phys Ther 2009;39(3):172-178.

- ↑ Harrop, James S; Naroji, Swetha; Maltenfort, Mitchell; Anderson, D. Greg; Albert, Todd; Ratliff, John K; Ponnappan, Ravi K; Rihn, Jeffery A; Smith, Harvey E; Hilibrand, Alan; Sharan, Ashwini D; Vaccaro, Alexander. Cervical Myelopathy: A Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation and Correlation to Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. Spine 10 February 2010 [epub ahead of print]

- ↑ Yonenobu K, Abumi K, Taketomi E, Ueyama K. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the japanese orthopaedic association scoring system for evaluation of cervical compression myelopathy. Spine(Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Sep 1;26(17):1890-4;discussion 1895

- ↑ Kadanka Z, Bednarík J, Vohánka S, Vlach O, Stejskal L, Chaloupka R, Filipovicová D, Surelová D, Adamová B, Novotný O, Nemec M, Smrcka V, Urbánek I. Conservative treatment versus surgery in spondylotic cervical myelopathy: a prospective randomised study. Eur Spine J (2000) 9 :538–544

- ↑ Annemie I. F. Spooren, Yvonne J. M. Janssen-Potten, Eric Kerckhofs and Henk A. M. Seelen .outcome of motor training programmes on arm and hand functioning in patients with cervical spinal cord injury according to different levels of the icf: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 497–505

- ↑ Massimo Leonardi, Norbert Boos , Degenerative disorders of the cervical spine

- ↑ 7 Law MD Jr, Bernhardt M, White AA 3rd.Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a review of surgical indications and decision making. Yale J Biol Med. 1993 May-Jun;66(3):165-77.

- ↑ G. Aufdemkampe, J.B. Den Dekker, I. Van Ham, B.C.M. Smits-Engelsman, P. Vaes. Jaarboek fysiotherapie-kinesitherapie 2000. Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, 275 p

- ↑ videorehab. Clonus. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9XWmpBz4BVo [last accessed 09/03/13]

- ↑ videorehab. Hoffman's Positive. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QjtiasgMgwY [last accessed 09/03/13]

- ↑ The Gait Guys. A Gait Case of Combined Spinal Myelopathy and Trendelenburg Pathologies. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYmzQL_NSeI[last accessed 09/03/13]|}

- ↑ ABHISHEKA KUMAR. Deep Tendon Reflexes. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EfZo6aJDn_Q[last accessed 09/03/13]|}

- ↑ Stanford University. Imaging Patients with Myelopathy. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mJVEtq5GsJk[last accessed 09/03/13]