Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Rehabilitation Class: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

COPD is a major contributor to healthcare costs UK-wide. | COPD is a major contributor to healthcare costs UK-wide. There are approximately 900,000 diagnosed COPD cases in the UK, and it has been estimated that the actual number - including undiagnosed cases - may be as high as 3 million (Khdour, et al., 2011; NICE, 2011). <br> | ||

<br>In 2003, the UK segment of the Confronting COPD survey estimated that the average annual direct costs per patient to the healthcare system came to £819.42, while average indirect costs – to society via paid sick leave, lost productivity, additional burden of care and so forth – come to £819.66. UK-wide, 24 million lost working days, amounting to 9% of all certified sick leave, are attributable to COPD – nearly 20 times that of asthma. More than 44% of COPD patients in the UK were found to be below retirement age at the time of the 2003 survey. 24% of all COPD patients were completely unable to work due to the disease, while 9% were limited in their ability to work and 5% had to miss work because of the disease. An estimated 4808 total workdays were lost to COPD in the 12 months preceding the survey, averaging at 12.02 days per patient (Britton, 2003). <br><br> | <br>In 2003, the UK segment of the Confronting COPD survey estimated that the average annual direct costs per patient to the healthcare system came to £819.42, while average indirect costs – to society via paid sick leave, lost productivity, additional burden of care and so forth – come to £819.66. UK-wide, 24 million lost working days, amounting to 9% of all certified sick leave, are attributable to COPD – nearly 20 times that of asthma. More than 44% of COPD patients in the UK were found to be below retirement age at the time of the 2003 survey. 24% of all COPD patients were completely unable to work due to the disease, while 9% were limited in their ability to work and 5% had to miss work because of the disease. An estimated 4808 total workdays were lost to COPD in the 12 months preceding the survey, averaging at 12.02 days per patient (Britton, 2003). <br><br> | ||

Revision as of 21:45, 14 November 2012

Community Rehab COPD[edit | edit source]

Executive Summary

[edit | edit source]

Background Information

[edit | edit source]

Disease Process[edit | edit source]

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) describes a number of conditions including chronic bronchitis and emphysema, where people have difficulty breathing due to long term damage to their lungs. Individuals with COPD will often have a mixture of both chronic bronchitis and emphysema. COPD leads to permanent damaged airways, which causes them to become narrower making it difficult for air to go into and out of lungs (NHS 2012). Chronic bronchitis is defined as inflammation of the bronchi, which increases muscus production in airways and, thus, causes obstruction. Emphysema involves the alveoli losing their elasticity and support which causes them to narrow and trap air in lungs during expiration. This also causes problems with oxygen delivery, which may result in increased work of breathing and shortness of breath (British Lung Foundation 2012). The pathophysiological changes that occur to the lungs depends on the nature of the patients disease.

Causes[edit | edit source]

The largest single cause of COPD is cigarette smoking (British Lung Foundation 2012). The likelihood of developing COPD increases the more the patient smokes and the longer they have been smoking (NHS 2012). Smoking cessation will gradually reduce the patient's chances of getting COPD as it slows down the process. Other potential causes of COPD included:

- Exposure to air pollution

- Exposure to fumes or particles at work, for example, welding fumes or coal dust

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, a genetic condition

Common symptoms of COPD are: cough, sputum production, shortness of breath, fatigue and decreased physical activity ability (NHS 2012).

Impact on QoL: [edit | edit source]

There is a large impact on quality of life for individuals living with COPD including, but not limited to;

- Decreased exercise tolerance

- Decreased ability to carry out activities of daily living (ADLs)

- May have a reduced income due to the patient’s inability to work (loss of productivity) (NHS 2012).

Willgoss et al. (2011) illustrated that many people living with COPD also suffer from

- Anxiety

- Feelings of isolation

- Decreased social participation

- Inability to carry out ADLs which all affect quality of life

Stahl et al. (2005) determined that health related quality of life (HRQL) in COPD deteriorates in parallel with lung function impairment; HRQL decreases with increasing severity of the disease. They also found that HRQL deteriorates with increasing age.

Epidemiology Of COPD[edit | edit source]

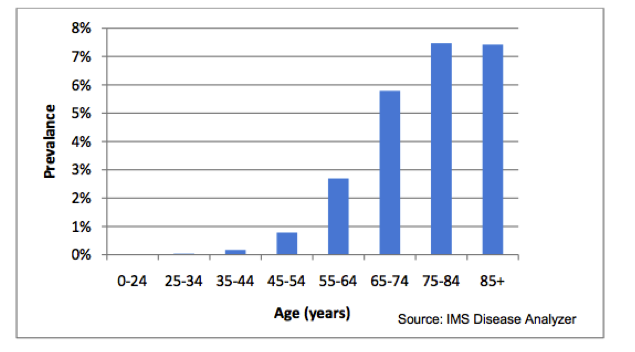

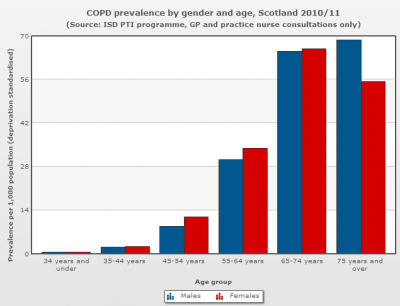

COPD is the 5th largest killer in the UK. It is the 2nd most common cause of emergency admission to hospital and it is the most costly inpatient condition treated by the NHS (NHS 2012). An estimated 3 million people have COPD in the UK although approximately 2 million of this estimation remain undiagnosed (NICE 2011). COPD affects more men than women, although rates of women with COPD are climbing (NHS 2012). The rate of COPD in the population is estimated at between 2% and 4% and the diagnosed prevelance of COPD in England alone is 1.6%. The prevalence of COPD is largely influenced by age. The diagnosed prevelance for individuals aged 45-54 is < 1% which increases to > 5% for individuals aged 65+ (NICE 2011). This is depicted in Figure 1. The mortality rate of COPD in the UK is estimated at 23,000 people per year.

Figure 1: Estimated prevalence of diagnosed COPD by age (NICE 2011):

Cost To NHS[edit | edit source]

In the UK the NHS is currently spends approximately £1 billion annually on COPD. It costs nearly 10 times more to treat severe COPD than the mild disease (Department of Health 2012).

Current Service And Achievements[edit | edit source]

There are currently many guidelines and initiatives for COPD; NICE guidelines, British Thoracic Society guidelines, GOLD: global initiative for COPD, NHS improvement. All of these guidelines discuss the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation. There is currently an NHS stop smoking service available in Lothian that offers one-to-one support. Hospital based pulmonary rehabilitation programs are also available throughout the UK.

As of 2009, over 1,400 people have been referred to pulmonary rehabilitation in Lothian with a drop out rate of 25% (NHS Lothian 2009). There is clear evidence accoring to a Lothian pulmondary rehabilitation service audit (2009) that the majority of patients who engaged in pulmonary rehabilitation show immediate benefits and sustained benefits of a year after the program. These benefits include:

- an increased exercise tolerance (improvements have shown to be sustrained at 1 year follow up)

- significant improvements to HRQL

- reduction in exacerbation

- reduction in number of admissions

The evidence therefore suggests there are numerous clinical benefits associated with pulmonary rehabilitation (NHS Lothian 2009)

Rationale For Change: [edit | edit source]

Pulmonary rehabilitation is an exercise program combined with educational information. It can increase an individual’s exercise capacity, mobility and self-confidence leading to an increased quality of life (NHS 2012). Exercise has been shown to improve quality of life, control symptoms and decrease exacerbations and hospital re-admissions (AUDIT).

Although there are more males with COPD the rates of women with COPD are rising (Department of Health, 2011). Thus we are suggesting that an all female pulmonary rehabilitation class may increase the uptake of females as well as adherence to exercise. It has been demonstrated that .... EVIDENCE?! DISCUSSION - according to the audit that sheena sent out - there are equal number of men and women referred to pulmonary rehabilitation in lothian.....

Pulmonary rehabilitation based in a community sports facility may increase adherence, as it may be more accessible and individuals may feel less anxious about a class held in a community setting as opposed to a hospital.

Evidence To Support Pulmonary Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

“The opportunity for structured, on-going exercise with peer and professional support, in a suitable venue, is perceived as important to people with COPD in facilitating a physically active lifestyle following pulmonary rehabilitation” (Hogg et al. 2012, pp. 189).

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2010 guidelines for COPD management states that there is evidence to show that pulmonary rehabilitation:

- Elicits meaningful improvements to health-related quality of life, functional and maximum exercise capacity in COPD patients

- Reduces dyspnoea

- Shows a trend towards decreased total hospitalisation days and total incidences of hospitalisation required for COPD patients in the years following a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation versus the year prior to rehabilitation

- Improves cost-effectiveness in terms of cost per quality of life-adjusted year (QALY) gained versus conventional treatment.

- Has a significantly greater effect on the above outcomes than bronchodilator drugs

Ries et al. (1997) reported that pulmonary rehabilitation brings about improvements in health-related quality of life and functional and maximal exercise capacity. In addition, they also report that it has a positive impact on dyspnoea, which, as previously mentioned, is a common problem for individuals with COPD (Ries et al., 1997). British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Subcommittee on Pulmonary Rehabilitation (2001) also support the finding that pulmonary rehabilitation reduces dyspnoea. Although there is mixed findings in regards to the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation, trends in study findings suggest that it reduces total hospitalisations (NICE, 2010) and significantly improved number of days in hospital (Griffiths, 2000). It has also been shown that, when compared to traditional COPD treatment, pulmonary rehabilitation showed improved cost-effectiveness in terms of cost per quality of life-adjusted year (QALY) gained. This is an important measure in this population as quality of life has been shown to decrease with COPD (Griffiths et al., 2001). In addition, NICE states that participation in pulmonary rehabilitation has a greater effect than use of bronchodilators in people with COPD (NICE, 2010).

Analysis Of The Needs For COPD Exercise Rehabilitation Classes[edit | edit source]

PESTLE (political, economic, social, technological, legal environmental)[edit | edit source]

Historical Trends and Future Projections for NHS Budget Changes

[edit | edit source]

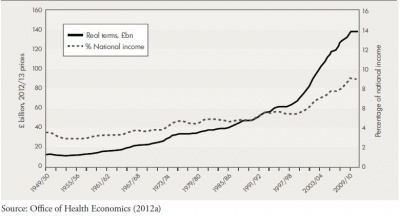

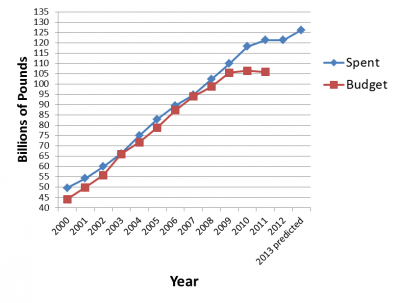

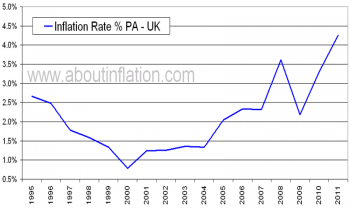

According to Crawford & Emmerson (2012), real public spending* on the NHS has increased faster than economy-wide inflation since the 1950s – from 3.5% of the national income in fiscal year 1949-1950 to 7.9% in fiscal year 2007-2008, prior to the financial crisis and subsequent recession.

* Spending which has been adjusted for the effect of the general level of inflation in the economy.

The fastest rate of average growth on record was 6.4% per annum between fiscal years 1996-1997 and 2009-2010. In the 2010 Spending Review, the UK government committed to protecting NHS funding for that year to ensure adequate healthcare delivery to UK citizens. However, a freeze for NHS spending has been planned for fiscal years 2011-2012 to 2014-2015. If implemented, it will be the tightest 4-year funding period on record for the past 50 years (Crawford & Emmerson, 2012).

Figure 2: History of UK NHS Spending

(Crawford & Emerson, 2012)

Projected total public spending cuts average at 0.9% per annum from fiscal years 2015 to 2017. Even with significant cuts in welfare spending, public services spending require average cuts of 1.7% per annum to conform to current spending plans. For spending on public services to increase by an average of 1.1% per annum from 2014 to 2022, total public spending must increase proportionate to national income at a projected growth rate of 1.2% per annum over the same period. As can be seen from the above, changes to NHS and other public service funding are highly dependent on the actual economic climate of a given period – if average growth dips below forecasts, the amount available for public spending will be even lower (Crawford & Emmerson, 2012).

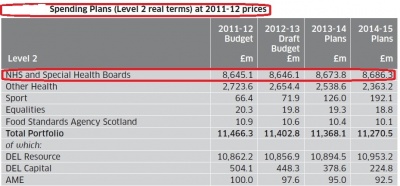

Figure 3: Spending Plans (Level 2) and Spending Plans (Level 2 real terms)

at 2011-12 prices (The Scottish Government, 2011)

In Scotland, the current spending review and latest draft budget includes plans to freeze real NHS spending between fiscal years 2012 to 2015, as can be seen from Figure 2 (The Scottish Government, 2011).

According to a report to the Holyrood health committee by Dr Andrew Walker of the University of Glasgow, NHS boards across Scotland have been directed to ensure 3% efficiency savings in fiscal year 2012-2013. Greater Glasgow and Clyde region leads the pack at a savings target of £58 million, with Lothian coming second at £27 million. Scottish Labour alleges that funding cuts have targeted mostly frontline staff, with more than 4500 NHS jobs cut since 2009, of which 2000 were nurses (BBC, 2012).

From the above, it may be seen that, across the UK, the NHS is experiencing a drastic shortage of resources with which to deliver healthcare. This shortage is being felt particularly in Scotland, where NHS boards nation-wide have been directed to make savings above the national average of 1.7% required to conform to spending plans. As a result, frontline care providers are being laid off, and it may be surmised that those who remain must take on even heavier workloads than before to compensate for the shortfall in personnel. As such, the NHS and its staff must make more efficient use of dwindling resources than ever before to ensure adequate healthcare delivery to those in need.

COPD cost to NHS and Society

[edit | edit source]

COPD – Its Costs To The NHS And Burden On Greater Society

COPD in the United Kingdom

COPD is a major contributor to healthcare costs UK-wide. There are approximately 900,000 diagnosed COPD cases in the UK, and it has been estimated that the actual number - including undiagnosed cases - may be as high as 3 million (Khdour, et al., 2011; NICE, 2011).

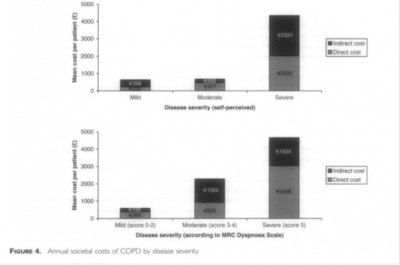

In 2003, the UK segment of the Confronting COPD survey estimated that the average annual direct costs per patient to the healthcare system came to £819.42, while average indirect costs – to society via paid sick leave, lost productivity, additional burden of care and so forth – come to £819.66. UK-wide, 24 million lost working days, amounting to 9% of all certified sick leave, are attributable to COPD – nearly 20 times that of asthma. More than 44% of COPD patients in the UK were found to be below retirement age at the time of the 2003 survey. 24% of all COPD patients were completely unable to work due to the disease, while 9% were limited in their ability to work and 5% had to miss work because of the disease. An estimated 4808 total workdays were lost to COPD in the 12 months preceding the survey, averaging at 12.02 days per patient (Britton, 2003).

Figure 4: Annual societal costs of COPD by disease severity

(Britton, 2003)

As can be seen from Figure 4, the later stages of COPD cause an across-the-board increase in direct and indirect costs, the former being attributable mostly to hospitalisation.

At the time of the survey, COPD prevalence in the UK was calculated to be 5% amongst males aged 65-74 years of age, and 10% in males aged 75 years or more . Given the prevalence increase of 25% in males and 69% in females from 1990 to 1997 (Britton, 2003), if this trend continues in the future or prevalence remains the same with an increasing population, the burden of COPD on the healthcare system will only increase, particularly as the population ages, allowing COPD to progress to its later and more care-intensive stages.

COPD in Scotland

ISD Scotland observed that the above-mentioned trend was already in effect in Scotland by 2007, with 42,700 diagnosed female COPD cases in Scotland versus 36,200 male. The gap between male and female COPD prevalence has only widened since then, with 48,630 female versus 40,520 male by end-2010 (ISD Scotland, 2011).

Figure 5: COPD Prevalence by gender and age, Scotland 2010/11

(The Scottish Public Health Observatory, 2012)

According to Audit Scotland’s 2007 report, there are roughly 100,000 known cases of COPD in Scotland as of 2005, with a 33% increase in prevalence predicted for the next 20 years. COPD is the 3rd most common reason for hospital admission in Scotland, with 19% of patients readmitted more than once and 16% at least twice more, observed from 2003-2004 (Matthew & Diffley, 2007).

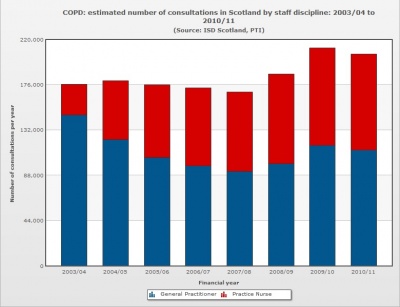

As of end-2010, the number of known cases in Scotland appears to have held more or less steady, ending the year at 89,170 documented cases (ISD Scotland, 2011), with minor fluctuations since 2005. COPD-related healthcare utilisation showed a definite rise from 2007 numbers, increasing from 173,860 doctor/practice nurse consultations in 2007 to 207,260 by end-2010 (ISD Scotland, 2011).

Figure 6: Estimated number of consultations in Scotland by staff discipline:

2003/04 to 2010/11 (The Scottish Public Health Observatory, 2012)

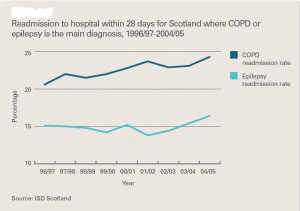

COPD’s direct per-annum cost to NHS Scotland is estimated at £100 million, as can be seen from Figure 8. As can be seen from Figure 7, inpatient stays have shown a steady downward trend in duration from 1997 to 2005. However, readmission rates have been rising over the same period, as seen in Figure 9. From Figure 8, it can also be seen that, compared to epilepsy patients, COPD patients have an average longer hospitalisation stay at each category of comorbidity (Matthew & Diffley, 2007).

Figure 7: Average length of stay for inpatients in Scotland Figure 8: Average length of stay in hospital for COPD

1997/98 to 2004/05 (Matthew & Diffley, 2007) and epilepsy patients in Scotland by number of

conditions present, 2004/05 (Matthew & Diffley, 2007)

NICE COPD guidelines suggest that average COPD patient per-annum costs to the NHS scale with severity accordingly:

Mild COPD: £150

Moderate COPD: £308

Severe COPD: £1307 (National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010)

Figure 9: Readmission to hospital within 28 days for Scotland Figure 10: Estimated cost of COPD services to the NHS

where COPD or epilepsy is the main diagnosis, 1996/97 to in Scotland (Matthew & Diffley, 2007)

2004/05 (Matthew & Diffley, 2007)

Figure 11: Estimated cost of COPD services per patient, Figure 12: A summary of the evidence for some

2004/05 (Matthew & Diffley, 2007) specialist COPD services (Matthew & Diffley, 2007)

A national average of £1036 (Figure 11) suggests that most known patients in Scotland have fairly severe disease. As can be seen from Figure 12, there is evidence for pulmonary rehabilitation potentiating large indirect savings by freeing up hospital beds for other patients by reducing inpatient stays. Although it has the highest initial setup cost of the services examined, once implemented, it is likely to pay for itself many times over in inpatient care costs saved (Matthew & Diffley, 2007).

With reference to earlier information on the dwindling funds available to public healthcare and rising incidence of COPD cases diagnosed and treated, a push to more widespread implementation of pulmonary rehabilitation would yield significant healthcare savings and improve treatment rates by freeing up beds for other patients.

National guidelines and targets

[edit | edit source]

Clinical Standards and Guidelines

National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in its 2010 guidelines for COPD management states that pulmonary rehabilitation is evidentially sound for:

- Eliciting meaningful improvements to health-related quality of life, functional and maximum exercise capacity in COPD patients

- Reducing dyspnoea

- Decreasing total hospitalisation days and total incidences of hospitalisation required for COPD patients in the years following a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation versus the year prior to rehabilitation

- Cost-effectiveness in terms of cost per quality of life-adjusted year (QALY) gained versus conventional treatment.

- Having a significantly greater effect on the above outcomes than bronchodilator drugs

It was also recommended that referral to pulmonary rehabilitation be considered at all stages of disease progression – as soon as symptoms and disability are present and not at predetermined impairment levels.

Additionally, it was noted that patients previously hospitalised for acute COPD exacerbation showed a tendency towards significant benefits from early pulmonary rehabilitation (within 1 month post-discharge), compared to patients receiving standard care modalities or no rehabilitation during this period. Evidential quality was low in the systematic review examined, but it was determined that there was no reason why patients who had a recent COPD exacerbation should not be considered for pulmonary rehabilitation.

NHS Lothian, 2011

The NHS Lothian COPD Guidelines concur broadly with the NICE 2010 Guidelines, agreeing that there is sufficient evidence that it is evidentially sound in its purported benefits to all COPD patients, and particularly those with severe to extremely severe COPD, or those scoring ≥ 3 on the Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale.

As with the NICE 2010 Guidelines, this guideline acknowledges that pulmonary rehabilitation:

- Improves exercise tolerance

- Improves Quality of Life

- Reduces symptoms

- Reduces number of exacerbations

- Reduces hospital admissions

Given that pulmonary rehabilitation is available in all Community Health Partnerships (CHPs) throughout Lothian, this guideline recommends that all patients with repeated exacerbations or who are hospitalised for exacerbations be fast-tracked for pulmonary rehabilitation.

NHS Quality Improvement Scotland, 2010

NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (QIS) lists 6 dimensions of quality practice:

- Safe: avoiding iatrogenic patient harm

- Effective: providing scientifically-based service to all who could benefit, refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit.

- Patient-centred: providing care respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

- Timely: reducing waits and harmful delays for both care recipients and givers.

- Efficient: avoiding waste, inclusive of equipment, supplies, ideas and energy.

- Equitable: providing care quality that does not vary due to personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location and socioeconomic status.

Furthermore, it also acknowledges both the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation on COPD patients with regard to improving health-related quality of life, exercise capacity and breathlessness, particularly in the wake of acute exacerbation.

Taking into account the cost-effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation as estimated in Matthew & Diffley (2007) and echoed in the NICE 2010 Guidelines, it may be seen that an early post-discharge pulmonary rehabilitation programme would fulfil dimensions #1 – 5 of NHS QIS’ quality outcomes.

In summary, multiple major sources of clinical standards and guidelines agree that pulmonary rehabilitation is an effective treatment modality for improving health-related quality of life outcomes in patients, modulating symptoms, reducing incidences of exacerbation and hospital readmission and need for medication, doing so in a safe, timely and cost-effective manner.

Patients' Experience of Pulmonary Rehabilitation Classes[edit | edit source]

The following are patients’ accounts of what life was like before starting a pulmonary rehabilitation programme for COPD, called Breath Smart, and how the rehabilitation classes have affected them.

Patient A’s Story: Back before I started at Breath Smart I couldn’t do a lot. I was heavily dependent on oxygen and practically house bound. I couldn’t use the stairs or do my gardening or go to the shops. I was actually wheeled into my 1st class at breath smart because I couldn’t walk far at all. I must have been in hospital 8 or 9 times the year before I started these classes. I’ve been coming twice a week for just over a year and now I don’t use any oxygen at all and I will gladly take the stairs without and trouble. I haven’t been admitted to hospital once this year. I can now use the treadmill for 25mins at a time at a speed of 5.5km/hr and an incline of 3.5. I never thought this would be possible. Breath Smart has given me back my freedom I can’t begin to explain the changes it has made to my life. I am however still smoking. If I was able to improve this much while still smoking I can only imagine how much better I would be if I could give them up but I haven’t been able to as of yet.

Anne’s Story: Before starting Breath Smart I spent a lot of time in hospital, my breathing was very bad and my general health was very bad also. I used an awful lot of oxygen. Confidence was a big problem. It was hard to know what to do, that was very very difficult. I had been very very active all my life and then everything came to a standstill. My consultant suggested I come to Breath Smart. I’m here 2 years now, and the difference in my life is huge! I couldn’t even start to tell people how much of a difference it has made to my life, but I do tell people. My family have all seen the difference it has made to my life. I’m more active. Coming to breath smart gives you an incentive, it gives you the confidence, the people here are professional you trust them, I trust everyone here they are very very good, they explain to you and tell you if you are doing too much or doing too little. This is the 1st year that I haven’t been in hospital since I was diagnosed.

Richard's Story

Bob's Story

John's Story

Kevin's Story

NOTE ABOUT CONSENT?

(ie) All patients above have given consent for name and story to be shared with physiopedia.... or something along those lines???

Option Appraisal[edit | edit source]

A recent survey highlighted that it is only available in 25% of U.K. hospitals (Davidson and Morgan, 1998) limiting the number of COPD patients that can benefit. There are a variety of settings in which pulmonary rehabilitation services can be provided. Traditionally services were based in hospital inpatient and outpatient settings, but there is growing interest in developing services in community and home settings making it easier for patients to attend and carry out.

Location is stated as a core element in the full clinical guideline on COPD, it states that for pulmonary rehabilitation programs to be effective and to improve compliance, they should be held at times that suit patients, in buildings that are easy for patients to get to and have good access for people with disabilities (NICE, 2010). Pulmonary rehabilitation has been found to have a positive impact on lowering health care costs, mainly by reducing the number of exacerbations and hospital admissions (Guëll et al., 2008).

Table 6: Advantages and disadvantages to pulmonary rehabilitation in a hospital setting

| Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Peer support | Difficulty parking – possible |

| No external costs, i.e. rent | Busy environment |

| Patients may deem hospital appointments more important | Lack of available, purposeful space |

| Qualified medical staff | Limited exercise equipment |

| Safe, controlled environment | May associate hospital with acute illness |

| Medical equipment available | Increased chance of contracting an infection |

| Exercise equipment available | Costly, even in outpatient setting |

| Cost comparison found most efficient form of delivery | Suffer from high drop out rates with 20% not completing the program |

| Found to be effective in improving exercise tolerance and QoL | Patients discouraged because of frequent journeys to hospital |

| Patients often have difficulty getting to a hospital |

Table 7: Advantages and disadvantages of pulmonary rehabilitation in a community setting

| Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Peer support | External costs i.e. rent, travel expenses, equipment, resources |

| Motivational environment encouraging compliance | Patients may want to take part more anonymously |

| Familiar, friendly atmosphere | |

| Low drop out rates | |

| Sufficient amount of exercise equipment | |

| Available, purposeful space | |

| More involved within the community | |

| Qualified physiotherapists | |

| Relaxed atmosphere so patients feel more comfortable raising questions/issues | |

| Influence patients participation in physical activity | |

| Greater choice of venue making it more accessible | |

| Local ownership |

Table 8: Advantages and disadvantages of pulmonary rehabilitation in a home setting

| Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Cost effective | Safety |

| No supervision | Adherence |

| Patient may feel safer and more comfortable exercising in own home | Information clear and well instructed? Patient understands and carries out correctly? |

| Can do it at time that suits patient | No supervision |

| No peer support | |

| Any issues that arise may not be addressed immediately | |

| Feasibility of resources and equipment – cost, availability | |

| Practicalities of having equipment in home i.e. space |

Following a review of the evidence a community setting was chosen for the pulmonary rehabilitation program. Evidence showed pulmonary rehabilitation provided in a community setting has comparable benefits to that produced in a more customary hospital-based setting, with both settings producing significant improvements in exercise capacity and quality of life (Maltais et al., 2008: Guell et al., 2008: Waterhouse et al., 2010). The choice of venue has been found to be determined by local factors of convenience, current availability of resources and incremental costs as supported by Waterhouse et al. (2010). When health economic analysis was considered by Waterhouse et al. (2010) it revealed that neither hospital nor community based programmes were preferential. Benefits of having the class in a community setting aided attendance and compliance helping not only patients but in the long run saving the NHS money by preventing exacerbations and reducing hospital admissions.

Evidence suggests that there appears to be no clinical or cost benefit of community based pulmonary rehabilitation programs over hospital based pulmonary rehabilitation and that the venue may be best determined by local access preferences and transport links reinforcing current recommendations in NICE CG101 (Nice, 2010).

Proposed Class Structure[edit | edit source]

Our Proposed Class Structure:[edit | edit source]

Table 9: Proposed Class Structure

OR

| Structure | Additional Information |

| 2 supervised classes a week with 1 hour of exercise per class for 10 weeks |

Encouragement to do at least Rolling classes If a patient feels the need they can return for a top-up session |

| Health Check | See appendix 1 |

| Warm-up | |

| Cardiovascular exercise |

To be recorded on exerxise sheets (see appendix 2) Intensity: 4-6 on dyspnoea scale (see appendix 3) Duration: Building up to 30mins |

| Strengthening exercise |

2-4 sets 6-12 reps 50-80% of 1RM |

| Cool down | |

| Health checks | |

| Refreshments and Education | Short education session and time for participants to ask questions |

Evidence To Support Our Proposed Class Structure:

[edit | edit source]

Eligibility for the proposed pulmonary rehabilitation program shall be in line the NICE COPD guideline (2010). This states that “pulmonary rehabilitation should be offered to all patients who feel functionally disabled by COPD” (NICE 2010).

“The opportunity for structured, on-going exercise with peer and professional support, in a suitable venue, is perceived as important to people with COPD in facilitating a physically active lifestyle following pulmonary rehabilitation” (Hogg et al. 2012).

According to General Practice Airways group's sharing of best practice meeting (2005) and the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement on Pulmonary Rehabilitation (2006), at least one supervised session is required per week for effective pulmonary rehabilitation. It has also been suggested that two supervised sessions per week may have a better impact on health-related quality of life compared to one supervised session (Liddell and Webber 2010).

Making rehabilitation a regular weekly program would give the program structure and would ensure that the participants have regular support which has been found to be important in exercise regimes, especially in this population (O'Shea et al. 2007). Therefore, to make this program as cost effective as possible, we suggest that it should contain two weekly exercise classes as a number of individually supervised rehabilitation sessions would be capital and labour intensive.

As is desirable, exercise sessions would be delivered by healthcare professionals, including a physiotherapist and physiotherapy technical instructor, with experience in cardio-respiratory rehabilitation (Backley et al. 2005). As previously stated, the location of these sessions would be in the community as according to the COPD guidelines published by NICE, pulmonary rehabilitation classes should be held in locations which are easily accessed by participants to ensure their effectiveness (NICE 2010). In addition, it has been found that difficulties with transport is a barrier to completion of pulmonary rehabilitation (Keating et al. 2011) so having the classes in the community should reduce transport problems.

The NICE guideline also states that rehabilitation classes should be held at times which suit the participants (NICE 2010). This would be arranged with the participants early in their journey through the program. Group sessions would be interspersed with exercise sessions which participants would do in their own time at home or in a local leisure facility. It is suggested that a minimum of four home sessions are completed per week (Backley et al. 2005).

As recommended by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement on Pulmonary Rehabilitation (2006), a minimum of twenty exercise sessions would be included in this pulmonary rehabilitation program at a frequency of at least three per week. According to the NICE COPD guideline (2010), duration of initial pulmonary rehabilitation should be between six and 12 weeks. To conform to both of these guidelines, we propose a 10 week pulmonary rehabilitation program consisting of two supervised sessions per week.

Although exercise of varied intensity has been shown to be beneficial for people with COPD, high intensity exercises would be encouraged in this rehabilitation program for greater physiological effects (Nici et al. 2006). In addition to the traditional lower limb training normally included in pulmonary rehabilitation, such as walking or cycling, upper limb exercises, such as arm ergometer or hand weight exercises, will be included as a number of beneficial effects have been noted including reduce ventilatory requirements while using the arms (Couser et al. 1993, Epstein et al. 1997).

Ideally, the rehabilitation program would contain aerobic exercise at an intensity of between four and six on Borg dyspnoea scale or more than 60% of max workload for at least 30 minutes. For resistance exercise, between two and four sets of six to twelve repetitions at an intensity of 50-80% of 1RM would ideally be performed (Nici et al. 2006).

In addition to the structured exercise class, an essential educational component will be included in the pulmonary rehabilitation program (Backley et al. 2005). This would include teaching participants the importance of exercise, which is of specific importance as many individuals with COPD elect not to take up a referral to pulmonary rehabilitation as they think they would not experience any health benefits. Ensuring good attendance at pulmonary rehabilitation requires consideration of how information regarding the proven benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation can be conveyed to participants (Keating et al. 2011). It is also important to supply the participants with information on how to transfer exercise into environments outside the class, such as their home, as this will be required for between supervised sessions and once they have completed the program (Nici et al. 2006). Information on relaxation, anxiety management, medication and self-management (Backley et al. 2005), including an action plan for exacerbations (Nici et al. 2006), would also be included as this seen as being essential in an effective pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Financing[edit | edit source]

Fixed Expenses:

Below is a table indicating the fixed costs of the “insert name” class by year and by month.

Table 10: Fixed Expenses

| Expenses | Yearly | Monthly |

| Venue | 3600 | 300 |

| Staff (Band 5 Physiotherapist) | 2027.52 | 168.96 |

| Staff (Physiotherapist Assistant) | 1110.24 | 92.52 |

| Personal Indemnity Insurance | Covered by CSP Membership | Covered by CSP Membership |

| Total | £6737.76 | £561.48 |

To calculate the staffing costs we used the following stepped equation:

1. Number of workable hours per year

- Number of weeks per year X hours worked per week

- 52 X 37.5= 1950

2. Number of hours worked per year

- Number of workable hours per year– (Holiday + bank holiday hours)

- 1950 – [(27 X 7.5) + (8 X 7.5)]

- 1950 – (203 + 60)

- 1950 – 263

- 1687

3. Cost per hour for staff

- (Salary + Employers Contribution to National Insurance [13.08% for 2012-2013]) ÷ Hours worked per year

- Physiotherapist = 21,000 + 2750= 22750, 22750 ÷ 1687 = 14.08.

- Physiotherapist Assistant= 11500 + 1504.2 = 13004.2, 13004.2 ÷ 1687 = 7.71

4. Monthly Cost

- Cost per hour X hours per week X hours per month

- 2 class per week @ 1.5hr each = 3hrs per week

5. Yearly Cost

- monthly cost X 12

Variable Expenses:

Below is a table indicating the variable costs of the “insert name” class by year and by month.

Table 11: Variable Expenses

| Expenses | Once off | Yearly | Monthly |

| Stationary | |||

| Printer | 49.99 | 16.66 | 1.39 |

| Tea and Coffee | 96 | 8 | |

| Paper Cups | 48 | 4 | |

| Plastic Spoons | 24 | 2 | |

| Milk | 96 | 8 | |

| Total | £49.99 | £340.68 | £28.39 |

The cost of the printer was worked out as follows:

1. Yearly cost

- Cost of printer (priced at PC World) ÷ 3 (estimated minimal life expectancy)

2. Monthly cost

- Yearly cost ÷ months per year

Capital Expenses:

Below is a table indicating the capital costs of the “insert name” class by year and by month.

Table 12: Capital Expenses

| Expenses | Once Off | Yearly | Monthly |

| Blood Pressure Monitor X 4 | 160 | 53.33 | 4.44 |

| Pulse Oximeter | 198 | 66 | 5.50 |

| Total | £358 | £119.33 | £9.94 |

The cost of all capital equipment was worked out as follows:

1. Three quotes were explored and the average cost was taken

2. Yearly Cost

- Cost of item ÷ 3 (estimated minimal life expectancy)

3. Monthly cost

- Yearly cost ÷ months per year

Overhead Cost:

Fixed Expenses + Variable Expenses

Yearly overheads = £7078.44

Monthly overheads = £589.87

Starting Up Costs:

Capital expenses + 1st 3 month’s overheads

358 + (589.87 X 3)

358 + 1769.61

£2127.61

Cost of Service per participant:

(Overhead costs + Capital expenses) ÷ Number of participants

Yearly

(7078.44 + 119.33) ÷ 16

£449.86 per participant per year

Monthly

(589.87 + 9.94) ÷ 16

£37.49 per participant per year

Risk analysis[edit | edit source]

SWOT[edit | edit source]

To analyse the risks of our class being sucessful or not we performed a SWOT analysis looking at our Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats.

Strengths

When exploring the strengths of our proposed pulmonary rehabilitation classes we first assessed the strengths associated with the location of our class. They are as follows;

- The setting of a local gym is easy to access which may increase adherence to classes

- Being placed in the community may, potentially, cause less anxiety for participants than a hospital setting.

- The gym has more available space than most hospitals, thus, a greater capacity for participants.

- Since the rehabilitation program is not being run in the hospital, there is a lower chance of participants acquiring healthcare related infections.

This is followed by the strengths associated with our staff which include;

- Our program will have qualified staff including first aiders who are trained in defibrillator use.

- The physiotherapist will have cardiorespiratory education as part of their degree and experience in respiratory care. They will be able to provide answers to questions patients may have.

And finally the strengths of the class itself which include;

- Evidence shows that pulmonary rehabilitation gives numerous benefits to participants including improved quality of life

- There is an increasing body of evidence that pulmonary rehabilitation decreases long term costs to NHS. As Figure 5 and 6 demonstrate, the NHS, in real terms, is receiving less money. Therefore, projects like our proposed class would assist in maximising uitity for resources invested.

- The group exercise setting provides peer support which have been shown to benefit this population of people by helping to decreases feelings of isolation and increase confidence

- Addresses the need of some women feeling self-concious about exercise infront of men and thus, not doing so

- The class are free for participants therefore, those effected by inablility to work do not have to worry about how they will pay for the class, this may encourage more participants to take part.

Figure 5: UK Health Budget And Spending Figure 6: UK Inflation Rates

Weaknesses:

- Some participants may find a gym to initially be an intimidating setting. However they will be provided with information explaining that they will be exercising with other people who are of a similar age and have the same condition.

- Exercise is an undesirable activity for some participants, especially in people with COPD where breathlessness may be an issue. However they will be provided education on the benefits of exercise and what to expect from the classes.

Opportunities:

- There is a large prevalence and incidence of COPD, as indicated by figure Z, which provides a large pool of participants who may take part in our classes.

- Increased referrals to the program will reduce demands on NHS’s limited resources. Refer back to figure 5 and 6

- Greater exposure of pulmonary rehabilitation in the community will increase public awareness of this treatment option

- Studies have shown that femal patients are less

Figure 7: COPD prevalance by gender and age, Scotland 2010/11

Threats:

The primary threats to our propossed classes are other pulmonary rehabilitation classes:

- Some gyms run pulmonary rehabilitation classes. However, these are 1 to 1 sessions with a gym instructor so there is a lack of peer and group support. In addition, this rehabilitation program will have all the material delivered by health professionals with experience in respiratory care.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation is also often held in the hospital. We feel that our program setting is less intimidating and carries fewer negative connotations. There is also the additional benefit of more car parking facilities than what is available at most hospitals.

H & S[edit | edit source]

Conclusions[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Cost to NHS

paitent improvements

baseline measures

shuttle walk

10 rep max

Quality of life questionnaire

Health care utilisation questionnaire (6 month and 1yr follow up)

Patient imporvements:

Imporvements in baseline measures 1,2 and 3

Cost to NHS

reduction in health care utilisation

References[edit | edit source]

Backley, J., Bloom, J., Bott, J., Jones, R., Langley, C., Singh, S., Smith, J. and Till, J. 2005. A Summary of Recommendations of the Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Thecommunity- Sharing Best Practice Meeting. General Practice Airways Group pp.30/10/12. Available at: http://www.pcrs-uk.org/resources/gpiag_pul_rehab_bestpract_200306.pdf [Accessed 30/10/12].

BBC, 2012. commmissioningsuccess.com. [Online]

Available at: http://commissioningsuccess.com/2012/07/nhs-budget-squeeze-could-last-a-decade/

[Accessed 20th October 2012].

British Lung Foundation, 2012. COPD. [Online] Available at: http://www.blf.org.uk/Conditions/Detail/COPD#overview [Accessed 18th October 2012].

British Thoracic Society. Standards of care committee on pulmonary rehabilitation. 2001. Thorax, 56, pp.827-834.

Britton, M., 2003. The burden of COPD in the UK: results from the Confronting COPD survey. Respiratory Medicine, 97(Supplement C), pp. S71-S79.

Couser, J.I., Martinez, F.J. and Celli, B.R. 1993. Pulmonary rehabilitation that includes arm exercise reduces metabolic and ventilatory requirements for simple arm elevation. CHEST Journal, 103 (1) January 1, pp.37-41.

Crawford, R. & Emmerson, C., 2012. NHS and social care funding: the outlook to 2021/22, s.l.: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Davidson, A.C. and Morgan, M.D.L. 1998. A UK survey of the provision of pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax, 53, pp. 86.

Department of Health, 2012. Action plan for respiratory disease treatment published [Online] Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/05/nhs-companion-copd/ [Accessed 21st Oct 2012].

Epstein, S.K., Celli, B.R., Martinez, F.J., Couser, J.I., Roa, J., Pollock, M. and Benditt, J.O. 1997. Arm training reduces the VO2 and VE cost of unsupported arm exercise and elevation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, 17 (3) May-Jun, pp.171-177.

Gardiner, C. et al., 2010. Exploring the care needs of patients with advanced COPD: An Overview of the literature. Respiratory Medicine, Volume 104, pp. 159-165.

Griffiths, T.L., Phillips, C.J., Davies, S., Burr, M.L. and Campbell, I.A. 2001. Cost effectiveness of an outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Thorax, 56 (10) October 01, pp.779-784.

Griffiths, T.L., Burr, M.L., Campbell, I.A., Lewis-Jenkins, V., Mullins, J., Shiels, K., Turner-Lawlor, P.J., Payne, N., Newcombe, R.G., Ionescu, A.A., Thomas, J. and Tunbridge, J. 2000. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 355 (9201) Jan 29, pp.362-368.

Guëll, M.R., Lucas, P., Gáldiz, J.B., Montemayor, T., González-Moro, J.M.R., Gorostiza, A., Ortega, F., Bellón, J.M. and Guyatt, G. 2008. Home vs hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A Spanish multicenter trial. Archive Bronconeumol, 44 (10), pp.512-518.

Hogg, L., Grant, A., Garrod, R. and Fiddler, H. 2012. People with COPD perceive ongoing, structured and socially supportive exercise opportunities to be important for maintaining an active lifestyle following pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Journal of Physiotherapy, 58 (3) 9, pp.189-195.

ISD Scotland, 2011. Estimated numbers of consultations and patients consulting, by gender and age group. [Online]

Available at: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/General-Practice/Publications/2011-11-29/PTI_Nov11_COPD.xls

[Accessed 13 11 2012].

ISD Scotland, 2011. Estimated numbers of consultations, by staff type. [Online]

Available at: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/General-Practice/Publications/2011-11-29/PTI_Nov11_charts_consultations_COPD.xls

[Accessed 13 11 2012].

Keating, A., Lee, A.L. and Holland, A.E. 2011. Lack of perceived benefit and inadequate transport influence uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. Journal of Physiotherapy, 57 (3) 9, pp.183-190.

Khdour, M.R., Agus, A.M., Kidney, J.C., Smyth, B.M., Elnay, J.C. and Crealey, G.E. 2011. Cost-ultility analysis of a pharmacy-led self-management programme for patients with COPD. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 33, pp. 665-673.

Lacasse, Y., Goldstein, R., Lasserson, T.J. and Martin, S. 2006. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, CD003793.

Liddell, F. and Webber, J. 2010. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study evaluating a once-weekly versus twice-weekly supervised programme. Physiotherapy, 96 (1) 3, pp.68-74.

Maltais, F., Bourbeau, J., Shapiro, S., Lacasse, Y., Perrault, H., Baltzan, M., Hernandez, P., Rouleau, M., Julien, M., Parenteau, S., Paradis, B., Levy, R.D., Camp, P., Lecours, R., Audet, R., Hutton, B., Penrod, J.R., Picard, D. and Bernard, S. 2008. Effects of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149, pp.869-878.

Matthew, J. & Diffley, M., 2007. Managing Long-term Conditions, Edinburgh: Audit Scotland.

NHS, 2012. Chronic Obstructive Pylmonary Disease [Online] Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease/Pages/Introduction.aspx [Accessed 18th Oct 2012].

NHS Lothian, 2011. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Guideline, Edinburgh: NHS Lothian.

NHS Quality Improvement Scotland, 2010. Healthcare Improvement Scotland COPD services - Clinical Standards, Edinburgh: NHS Quality Improvement Scotland.

NICE. 2010. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care (partial update). NICE Clinical Guidelines, 101 (June) pp.1-61.

NICE, 2011. COPD Costing report: Implementing NICE guidelines [Online] Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13029/53292/53292.pdf [Accessed 18th Oct 2012].

Nici, L., Donner, C., Wouters, E., Zuwallack, R., Ambrosino, N., Bourbeau, J., Carone, M., Celli, B., Engelen, M., Fahy, B., Garvey, C., Goldstein, R., Gosselink, R., Lareau, S., MacIntyre, N., Maltais, F., Morgan, M., O'Donnell, D., Prefault, C., Reardon, J., Rochester, C., Schols, A., Singh, S., Troosters, T. and on behalf of the ATS/ERS Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing Committee. 2006. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 173 (12) June 15, pp.1390-1413.

O'Shea, S.D., Taylor, N.F. and Paratz, J.D. 2007. [horizontal ellipsis]But Watch Out for the Weather: FACTORS AFFECTING ADHERENCE TO PROGRESSIVE RESISTANCE EXERCISE FOR PERSONS WITH COPD. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation & Prevention, 27 (3) May/June, pp.166-174.

Ries, A.L., Bauldoff, G.S., Carlin, B.W., Casaburi, R., Emery, C.F., Mahler, D.A., Make, B., Rochester, C.L., Zuwallack, R. and Herrerias, C. 2007. Pulmonary Rehabilitation: Joint ACCP/AACVPR Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest, 131 (5 Suppl) May, pp.4S-42S.

Stahl, E., Lindberg, A., Jansson, S., Ronmark, E., Andersson, F., Lofdahl, C., Lundback, B. 2005. Health-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 3(56) September. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1215504/ [Accessed 20th October 2012].

Strijbos, J.H., Postma, D.S., van Altena, R., Gimeno, F. and Koëter, G.H. 1996. A comparison between an outpatient hospital-based pulmonary rehabilitation program and a home-care pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with COPD. A follow up of 18 months. Chest, 109, pp. 366-372.

Slovic, P., Finucane, M.L., Peters, E. and MacGregor, D.G. 2004. Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: some thoughts about effect, reason, risk and rationality. Risk Analysis, 24 (2), pp.311-322.

The Scottish Government, 2011. Scottish Spending Review 2011 and Draft Budget 2012-13, Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

The Scottish Public Health Observatory, 2012. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): primary care data. [Online]

Available at: http://www.scotpho.org.uk/health-wellbeing-and-disease/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd/data/primary-care-data

[Accessed 13 11 2012].

Ward, J.A., Akers, G., Ward, D.G., Pinnuck, M., Williams, S., Trott, J. and Halpin, D.M.G. 2002. Feasibility and effectiveness of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme in a community hospital setting. British Journal of General Practice, 52, pp.539-542.

Waterhouse, J.C., Walters, S.J., Oluboyede, Y. and Lawson, R.A. 2010. A randomized 2 x 2 trial of community versus hospital pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease followed by telephone or conventional follow-up. Health Technology Assessment, 14, pp.1-164.

Willgoss, T., Yohannes, A., Goldbart, J., Fatoye. 2011. COPD and anxiety: its impact on patients’ lives. Nursing Times. 107 pp. 15-16.

Appendices[edit | edit source]

Appendix 1 - Sample pre-exercise health check sheet[edit | edit source]

File:Pre-exercise health check.pdf

Appendix 2 - Sample Aerobic Exercise Recording Sheets[edit | edit source]

File:Exercsie class sheets.pdf

Appendix 3 - Rate of preceived dyspoena[edit | edit source]

File:Rate of Perceived Dyspnea.pdf

Appendix 4 - Measure Outcome For Quality Of Life[edit | edit source]

Appendix 5 - Sample Recording Sheet For Strengthening Exercises[edit | edit source]

File:Strengthening exercise recording sheet.pdf