Frail Elderly: The Physiotherapist's Role in Preventing Hospital Admission

Original Editors - Helene Slettebakk Gjerde, Alice Porteous, Benedicte Aarseth, Matthew Laird, Beth Donnelly as part of the QMU Contemporary and Emerging Issues in Physiotherapy Practice Project

INTRODUCTION

[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapy management of older adults is not a new concept however, as healthcare advances, the average age of the population increases and it is suggested that the prevalence of frailty will multiply[1]. Subsequently, this causes further demand on the NHS; an already overstretched service. In response to this, there has been an increased drive to improve the efficiency of the management of frailty. There has been a shift of care from reactive to preventative strategies and a focus on providing early interventions to reduce costly unplanned admissions to hospital[2]. Furthermore, from our experience on clinical placements and following discussion with expert clinicians, it became apparent to us that final year students may lack knowledge and awareness around the holistic management of frailty.

Consequently, this online learning resource has been created by a group of student physiotherapists and is tailored towards final year students and newly registered physiotherapists. This has been designed as an individual resource and should take 10 hours to complete.

[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, this a 10-hour interactive learning resource. This means you will be working through various learning materials, including multimedia resources, learning tasks and a case study.

These have been tailored for you in order to facilitate optimal deep learning[3] whilst considering different learning styles[4].

How much time to spend on each section:

1. Introduction: 30 minutes

2. Frailty: 1 hour

3. Policies & Guidelines: 30 minutes

4. Introduction to the Physiotherapist’s Role: 30 minutes

5. The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: 3 hours

6. Physiotherapy Treatment: 3 ½ hours

7. Conclusion: 1 hour

These time frames are intended as a guide and you should take adequate rest as required. Furthermore, this wiki has been designed to allow you to work through it in your own time and you are not required to complete it in one sitting.

Learning tasks you will encounter and what they involve:

|

In this section we will ask you to reflect upon your knowledge and skills

|

|

In order to facilitate learning, in this section we have created learning activities |

|

All information related to the case study will be presented here. |

|

In order to stay within the 10-hour timeframe and present a concise and |

The sections below will outline the aims and learning outcomes of this resource.

These have been created using the appropriate levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy[7] for final year students and newly registered physiotherapists in order facilitate a high level of thinking and learning.

Aims[edit | edit source]

This learning resource aims to...

- Provide you with an introduction to contemporary and emerging issues in the field of reducing hospital admissions in the frail elderly population and current management strategies.

- Provide you with an evidence-based overview of the physiotherapists’ role in the prevention of hospital admissions in the frail elderly population by using a holistic, patient centred approach

Learning outcomes[edit | edit source]

By the end of this learning resource you should be able to...

- Analyse the emerging issue of frailty in relation to the current context of health and social care in the UK.

- Critically evaluate the physiotherapist's role in the holistic assessment and treatment of frail individuals to prevent hospital admission.

- Evaluate the skills and knowledge gained from this resource, identifying appropriate application in clinical practice.

FRAILTY[edit | edit source]

In this section we will define and contextualise the contemporary and emerging issue that is frailty, providing demographics and the current climate of health and social care. This section is in relation to learning outcome 1.

|

Before commencing with this learning resource, take 20 minutes to reflect upon You might want to consider these questions:

|

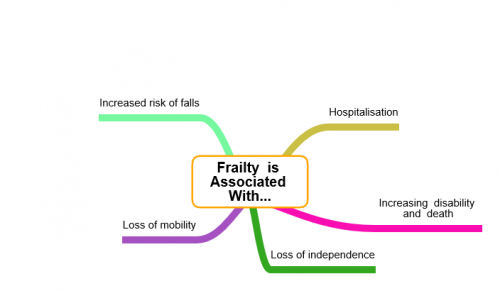

Definition[edit | edit source]

Frailty is defined as a “biological syndrome of decreased reserve and resistance to stressors, resulting from cumulative declines across multiple physiological systems and causing vulnerability to adverse outcomes"[8]. The British Geriatrics Society(BGS) supports that frailty is an age related health state affecting multiple body systems [9]. It is important to add that although frailty is age-related, it is not an inevitability.

Fit for Frailty[9] describe two basic models for frailty; the phenotype model and cumulative deficit model. The cumulative deficit model acts as an indicator of the severity of frailty, whereas the phenotype model is more descriptive and as such, has been included below (table 1).

| Phenotype | Description |

|---|---|

| Weight loss | A drop in bodyweight of ≥10lbs/4.5kg in the past year or a drop in bodyweight of ≥5% in the past year. |

| Weakness | Measured using grip strength. A result within the lowest 20 percentiles according to gender and BMI indicates a weakness. |

| Reduced energy/endurance | Self-reported, can also be a predictor of cardiovascular disease. |

| Slowness | The lowest 20 percentile of the population according to gender and standing height, 15ft walking time. |

| Low Physical activity | Based on reported activity levels translated into a kilocalories score. Again with a cut-off at the lowest 20 percentile for each gender. |

As professionals we must try to maintain an awareness of frailty and the impact that it will have for each individual despite their diagnosis. It can also be said there may be a stigma attached to a frailty diagnosis. It can have negative connotations for patients and family. Frailty and disability do not always co-exist however they can be linked, in some cases frailty may be a consequence of disability and in others may be the causation of disability[9].

| <span style="font-size: 13.28px; line-height: 19.92px;" /> |

For this online module we are considering the use of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, a multi-dimensional assessment tool, in the assessment and treatment of those deemed as frail.

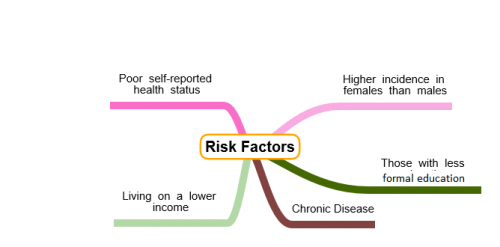

Demographics[edit | edit source]

Prevalence

• Risk of frailty increases with age, in those aged 65+ there is around a 10% incidence however this rises to between 25-50% in those over 85 years[11].

• The general trend is for greater incidence in females than males[12].

Ageing Population[edit | edit source]

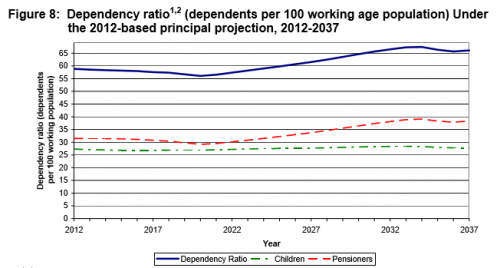

According to projections from the National Records for Scotland[13], the number of people over 75 is going to rocket by 28% over a ten year period from 2012 to 2022. In comparison, for those of working age there will be a 5% increase. This suggests that there will be a much larger proportion of the population regarded as elderly and therefore it is thought there will be an increase in the number of frail people within Scotland. This will push the number of dependants within the population to almost 70 per 100 persons in the working population by 2037 as demonstrated by the graph below from the National Records for Scotland[14].

A graphic produced by the Office of National Statistics[15] shows the population change from 1971 with predicted changes through until 2085. This graphic shows the significant change to a top heavy population in the coming 10-15 years.

Costs[edit | edit source]

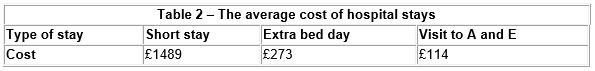

The next section will outline the length of stay and cost implications of frailty on the NHS.

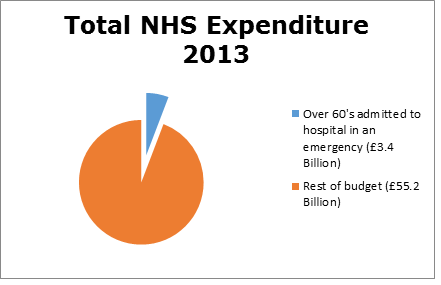

The latest UK statistics regarding hospital admissions and costs, which have been published relating to the years 2012-2013. Within this time frame 2,211,228 people over 60 were admitted to hospital in an emergency [16].

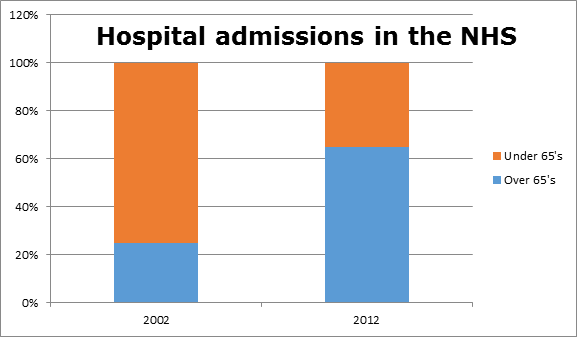

70% of day beds are occupied by people over 65; this is more than 51,000 beds at any one time. 85 year olds on average stay in hospital eight days longer than their younger counterparts[17].

|

Most emergency admissions to hospital happen through accident and emergency departments[16]. On average, a person over 85 spends 11 days in hospital[17]. If they pass through accident and emergency the total spent is approximately £3241 per patient, per visit. However, More than a 25% of over 85 year olds stay for 2 weeks and 10% stay longer than a month, when admitted as an emergency[18] . This means that even more money is spent.

|

410,377 elderly persons were admitted to hospital due to a fall in 2013. Appropriate strategies could prevent this by up to 30%.[19]

The length of time frail people stay in hospital differs throughout the world. The UK is 16th shortest in the world when it comes to average length of stay in hospital[20]. However, admittance to hospital and the cost implications of long term hospital stays are similar worldwide to the UK[21][22].

The above statistics show that elderly people can spend a prolonged time in hospital, some of which may not be necessary and is very costly for the NHS.

|

|

Relevance[edit | edit source]

Based upon the statistics and projections from The Scottish Government, over the next decade we will be faced with an ageing population with more elderly dependants. This means that there will be more of a financial strain on the NHS due to the prolonged hospital stays associated with age. This indicates a need for change avoiding costly hospital admissions unless absolutely necessary.

There are three ways the NHS can help reduce costs:

- Health and social care integration

- Preventative medicine

- Increased provision in the community[16].

Health and social care integration aims to increase the effectiveness of care while keeping associated costs low. The department of health report that at least one third of emergency admissions could be dealt with in the community.

Some ways of doing this are through:

- Telemedicine

- Risk prediction tools

- Case management

- Alternatives to hospitals[16].

Providing a free movement of information between hospitals and the community will allow increased communication and will reduce hospital admissions [18].

Preventative strategies include:

- “Encouraging healthy behaviours”

- Raising awareness of frailty

- Reducing Tobacco and alcohol use

- “Improving the environment to promote physical activity”[23].

Throughout this online Wiki module we shall discuss some of the current guidance from a variety of sources to help you work towards reducing hospital admissions in the frail elderly population with the view to reducing the strain on the NHS budget.

|

|

POLICIES AND GUIDELINES[edit | edit source]

This section will present the most relevant guidelines and policies in relation to frailty and highlight the most useful points.

It will discuss the current context of frailty in healthcare, aiming to enhance your understanding in relation to learning outcome 1.

The policies and guidelines included in this learning resource are:

|

| |

| Healthcare Improvement Scotland[26] | Think Frailty[27] | Fit for Frailty[28] |

These policies and guidelines were chosen as they are the most current Scottish and British documents focusing on frailty in relation to managing frailty in the community and preventing hospital admissions.

If you intend to work or are currently working out with the NHS you might be required to familiarilse yourself with policies in relation to your workplace.

Older People's Acute Care Improvement Programme (OPAC)[edit | edit source]

As the number of older people is increasing, there is an increased need to ensure appropriate care for them. Improving older people's acute care is a priority for the Scottish Government and in 2012 “The Older People’s Acute Care improvement programme (OPAC)”[26] was commissioned by the Scottish Government.

The programme focuses on 2 key areas

- Frailty

- Delirium

In relation to frailty, the programme focused on identification and immediate management of frailty. This included screening for frailty and ensuring that older people who were identified as frail received a comprehensive geriatric assessment within 24 hours of admission. [26]

The document “Think Frailty” explored the strategies implemented in practice in more depth and will be discussed in Section 3.2.

Healthcare Improvement Scotland[29] reported the impact of the programme and found that:

- Frailty screening in 3 surgical wards at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh decreased the length of stay, number of falls and number of complaints

- A reduced length of stay in NHS Grampian

- 50% decrease in the number of falls per month in 2 wards in NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

The report emphasises the importance to continue building on this work and Healthcare Improvement Scotland is committed to continue working with NHS Boards and staff to support learning and improvement of skills in relation to the management of frailty and delirium [29].

Think Frailty[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above the Scottish Government provided funding for Healthcare Improvement Scotland's policy to improve health care for older people due to the rising numbers of unplanned admissions of older people. There is strong evidence for the benefits of CGA for frail patients. The programme is aiming to ensure that 95% of frail patients have a CGA and are admitted or referred to a specialist unit within 24 hours of admission[27]

This case study report focuses on the work to identify frailty and ensure rapid CGA in four NHS boards in Scotland: NHS Ayrshire & Arran, NHS Grampian, NHS Lanarkshire and NHS Lothian.

Common themes underpinning the success in the NHS boards mention in the report included[27]:

Easy to use screening tool

The use of these should be at first point contact with older people; at the front door or at home

- Important to enable rapid identification and referral to CGA

- Valid screening tools reduces variability and increases the number of appropriate referrals to frailty services

Early intervention & Senior decision makers

- Senior decision makers were valued in particularly in NHS Ayrshire & Arran and NHS Grampian. As senior clinicians were more likely to use a wider range of care management options other than admission

- Early intervention focusing on discharge planning

Multidisciplinary team working

- Having a strong, integrated team was valued by all sites

- Good communication between the members of the MDT was important

- Common aim for all sites: Expanding the team. In particular physiotherapy and OT services so that a 7 day a week around the clock service is available

The sites involved in this project were able to show significant improvements in outcomes for the frail elderly presenting at the hospital.

These outcomes included a reduction in the number of admissions and re-admissions to hospital[27].

To read more about each NHS board strategies to improve frailty identification and management access Think Frailty: Improving the identification and management of frailty

Fit for Frailty[edit | edit source]

Part 1: Recognition and management of frailty in individuals in community and outpatient settings[28]

This part of the Fit for Frailty guidelines by the British Geriatric Society (BGS) are intended to support health and social care professionals working with frail older people in the community.

In order to recognise and identify frailty BGS recommends[28]:

- During all encounters with health and social care professionals older people should be assessed for frailty

- There are 5 main syndromes of frailty; Falls, change in mobility, delirium, change in continence and susceptibility to side effects of medication. Encountering one of these should raise suspicion of frailty

- Gait speed, timed up and go test and the PRISMA questionnaire are recommended outcome measures to assess for frailty

For managing frailty in an individual BGS recommends[28]:

- A Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), which involves a holistic, multidimensional and multidisciplinary assessment of an individual

- The result of the CGA should be an individualised care and support plan (CSP).

- The CSP includes a named health or social care professional coordinating the person’s care. A plan for maintaining and optimising the person’s care as well as urgent, escalation and end of life care plans

Gap in literature[edit | edit source]

Clinical guidelines provide evidence based recommendations in relation to the management of a specific condition or a syndrome. They are aiming to assist health and social care professionals in their decision making and help reduce undesirable variations in practice[30].

The guidelines on frailty discussed above are aimed to all health and social care professionals and it has been found that these rarely go in depth in their explanation of specific healthcare professional's roles. As physiotherapists it can be difficult to identify what recommendations are most applicable to our practice in relation to the management of frailty.

In the Fit for Frailty[28] guidelines it is suggested that physiotherapists should play a role in assessing and treating frailty.

It is reported that during every encounter with healthcare professionals, older people should be assessed for frailty. In addition to this, they also suggest that frail older adults would benefit from multidisciplinary assessment and intervention. Are physiotherapists routinely involved in this?

In the Think Frailty[27] document NHS Grampian reports physiotherapist are involved in the rapid MDT assessment team, seeing those who meet the frailty criteria. NHS Lanarkshire states that physiotherapists work in an early discharge team to see frail patient at the front door. Whilst NHS Lothian’s frailty screening tool suggests a referral to physiotherapy if the patient meets the appropriate criteria[27].

As argued above, the guidelines simply state that physiotherapists should be involved in the management of frailty,

but what is our main role?

The following sections of this learning resource aim to critically synthesise current evidence in order to present evidence based information on the physiotherapists role in assessing and treating frailty.

Resources

|

|

INTRODUCTION TO THE PHYSIOTHERAPIST'S ROLE[edit | edit source]

This section will introduce you learning outcome 2 and we will begin to explore the role of the physiotherapist in preventing hospital admissions in a frail elderly population.

The nature of the physiotherapy profession is to help restore movement and function in someone affected by illness or injury[33]. Physiotherapy input in the treatment for frailty is not a new concept. However, as previously discussed, the delivery of care is evolving in order to better meet the needs of this population. Physiotherapist’s are expanding their service to deliver intervention outwith standard inpatient care and moving to several different settings; for example, within day hospitals, in the patient’s home and in community clinics.

There is an emerging body of evidence supporting physiotherapy in emergency departments to assess and treat trauma and soft tissue injuries[34]. However, could physiotherapists be included in emergency services to assist in preventing admissions of frail patients?

In 2015, a physiotherapist joined forces with paramedics to treat non-life threatening emergency calls with the aim of preventing unnecessary A&E attendances and reducing hospital admissions. Commonly seen conditions included falls, chronic pain, decreased mobility, exacerbations of long-term conditions and frailty. 57% of patients remained at home and it is thought that £2850 was saved every time a patient was not transferred to hospital[35].

Furthermore, it has been suggested that physiotherapists could be stationed within hospital A&E departments to undertake frailty and falls risk screening and make rapid decisions on whether the patient can safely return to their pre-admission destination[36] [37]. However, little high quality research has been conducted and at present evidence is inconclusive, suggesting the need for further study in this area.

Whilst having an awareness of the different settings is important, the physiotherapy assessment and treatment is unlikely to vary from place to place.

THE COMPREHENSIVE GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT[edit | edit source]

The next section will cover the assessment of a frail individual. This relates to learning outcome two and three.

All the guidelines outlined above state a need for a CGA to be completed to diagnose patients who may be frail. From this assessment a holistic interdisciplinary treatment program can be devised to suit the problems and needs of the individual. The assessment is usually carried out by a geriatrician or another trained professional, such as a physiotherapist[38].

This assessment usually takes place when a patient is identified as possibly being frail; during acute illness, prior to surgery or when returning to a community environment. It is a multi-dimensional program, which looks at the patients; health (physical and mental), mobility and social status. This approach was introduced in 2001 by the Department of Health[39]. There are five domains in which assessment takes place.

Below is a table adapted from Martin[38], which identifies and outlines what should be included in each domain.

The methods used to achieve this are specific to the region of the UK in which you work. However, the measurement tools should be standardised and reliable. Some measures identify problems while others examine their severity.

The assessment will allow health professionals to identify the problems and allow for onward referral now and in the future. Once specific problems have been identified, onward referral can be made to appropriate healthcare professionals. This can then allow for a thorough assessment to be made around these problems. For example, a patient may be referred to physiotherapy to help increase mobility[38].

Benefits

A study examined whether a comprehensive assessment after an emergency admission is more effective when carried out by a team trained in a using a CGA. The paper showed that this approach reduced; costs, length of hospital stay, deterioration, mortality. Routine follow up appointments are an essential part of the CGA and identify effectiveness of treatment. There is no specifc time frame for these, yet follow up sessions usually occur when people are readmitted to hospital[40].

In hospitalised patients it has been shown to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and enhances management in both the long and short term[40][41]. Completing a CGA in the community can prevent reductions in mobility and problems which arise from poor mobility by implementing treatment programmes tailored to all the patients’ needs[42]. It can also reduce hospital stay, decrease the likelihood of readmission to hospital[43][44] and reduce mortality[45].

Why is this relevant to physiotherapy?

Below we have split the physiotherapy assessment into the CGA sections to show that physiotherapists can use its structure to help them carry out a comprehensive, holistic assessment.

Resources

|

|

How many of the key points can you recall? |

Functional capacity[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists have the knowledge and skill level to carry out the functional aspect of the CGA[46][47].

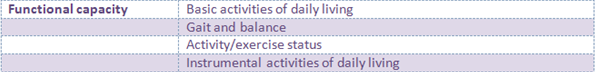

Here is a recap of the Functional Capacity section of the CGA:

There is a lack of evidence supporting the use of specific assessment techniques for physiotherapists to adopt to carry out a comprehensive functional assessment of a frail elderly person. However, there is a lot of evidence supporting the use of specific outcome measures within this population. These will be covered later in this section.

Due to the above gap only assessment techniques which have been reported in the literature will be included in this Wiki. There may be some common areas of assessment not covered; this does not mean they are not valid or useful to review when working with frail patients.

What is a functional assessment?

Functional assessments are a way of determining health needs now and in the future. Assessments of patients with frailty should occur after every illness or injury to establish the effect the episode had on the patient’s functional ability[48]. More specifically, functional assessments should be done on every patient over 75[49]. The functional assessment element of the CGA compromises of; gait, balance, abilities to carry out activities of daily living (both fundamental and basic) and activity/exercise status[38]. All these areas should be assessed by the attending physiotherapist.

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

The subjective assessment will be very similar to that of any other patient. Yet, some specific questions related to age and frailty must be asked.

1. Has anything changed recently in terms of the patients’; vision, hearing, mobility status, cognitive ability, medication usgae or activity levels[50].

2. Falls risk assessment tool (FRAT) questions should be asked which regard falls history and mobility status [51][50]. When did they last fall and why? how often do they fall? The context around circumstances of the fall should also be asked, like home set up and medication use[52].

3. It is useful to know how often the patient is eating and what foods they consume[53].

4. Do they have help or support with activities of daily living from anyone? Do they give help or support to anyone? [51].

|

|

Think about why the above questions are important to ask with this type of patient. This task should take 20 minutes. Answers are below |

1. It’s important to know any changes which could affect the rest of your assessment and treatment plans. How could these changes have impacted on the patients’ life? Can we help to change any issues/problems?

2. We need to know about any previous falls. This will help determine their mobility status and how well they are coping. The FRAT tool is helpful to determine future falls risk[52].We can then tailor treatment where it is needed[54] [55].

3.refer to medical section for answer.

4. You can get an idea of what ADL’s they are able to do, how they are coping with these demands and how busy they are throughout the day[56] [51].

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

The objective assessment should begin by observing posture, skin condition and body shape [57]. This can give you clues as to their general health and the extent of their frailty.

The therapist should have an idea as to what level of independence the patient has and how much physical activity they carry out on a daily basis[58][59]. This can be achieved by using outcome measures such as the timed up and go which has been shown to have good reliability and validity as a tool for measuring the mobility status of patients who are frail[60] . This type of information can also be gathered through the subjective assessment[58].

Gait

As gait speed is an important measure of frailty, it is important for physiotherapists to measure it. A speed of less than 0.8 m/sec indicates frailty [48]. Keeping track of the patient’s gait speed will enable the physiotherapist to objectively measure patient progress.

Endurance can be tested by completing multiple sit to stands or by carrying out a six minute walk test. Monitoring the patient's heart rate during this will give an indication of their bodies ability to respond to increased effort[59]. The six minute walk test has been shown to be valid and reliable within this population[61]. Measuring endurance gives the physiotherapist an indication of how far the patient is likely to be able to walk, which can aid treatment planning and goal setting.

Analysing the persons gait is also important. However, the difference in gait in people who are frail has not been widely researched. As well as frail individuals having reduced gait speed, they also have reduced stride length and cadence. Reductions in stride length are linked with the severity of frailty and come about due to sarcopenia and so lower limb weakness. It is advised that in order to truly assess gait the person should be asked to walk at their maximum speed[62].

Balance

Balance should be assessed comprehensively as this will allow for individualised treatment. 75% of over 70’s have reduced balance, which can increase falls[63]. Whilst some physiotherapists prefer using their own observations to assess balance, others favour the use of standardised outcome measures. The Berg Balance Scale, Single Leg Stance Test and Timed Up and Go were seen by physiotherapists as useful tools to measure functional ability[63]. Balance outcome measures were assessed in a systematic review for their psychometric properties. There are many which the physiotherapist can use; very few measure all aspects of balance. Testing a patients’ reactive balance was one area which was rarely examined. It is therefore important to know what aspects of balance and postural awareness are being tested by the OM so that treatment will be tailored to problems[64].

Reduced balance is linked with increasing falls and so hospitalisation[55].

Good indicators of falls risk are the Berg Balance Scale and the Tinneti Balance Assessment Tool as these look at functional balance[61][65]. Looking at patients' range of motion and strength can also help to evaluate chances of falls (see below).

A home assessment can identify if modifications need to occur to allow for increased safety[52]. See the Environment section.

Range of Motion (ROM)

Tibiotarsal range is important to measure as it can impact on posture and may therefore contribute to falls[59].

As previously mentioned, reduced grip strength is an indicator of frailty[10]. Grip strength can be tested by using a grip ball dynamometer and has been shown to be accurate and comfortable to use with people with frailty. It is important to measure grip strength as weakness can limit the patients’ ability to carry out activities of daily living[66].

Determining ROM is important with this population as a link between reduced lower limb mobility and fall prevalence has been found. Ankle plantarflexion and hip extension, internal rotation and abduction were found to be reduced[67]. It is therefore important to establish if your patient has reduced ROM as tailored interventions may help reduce falls.

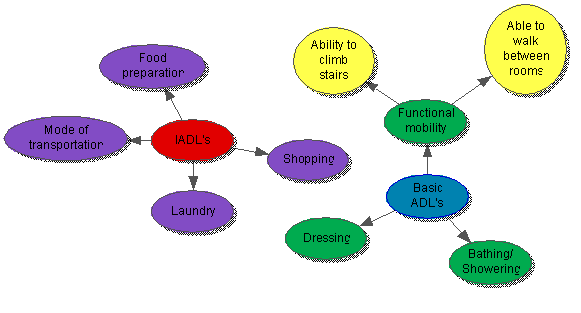

Activities of daily living (ADL’s) can help establish the range of motion and strength of frail patients. Two main types of ADL’s should be assessed, instrumental (IADL's) and basic[68][38].

- Basic ADL’s are self-care tasks, whereas,

- instrumental ADL’s are activities which are needed for a person to live independently in the community[69].

IADL’s are important to measure as an inability to do these is a better indicator of dysfunction than ability to self-care[69]. The percentage of elderly people reported as being independent increased to 65.4% (from 46.5%) when looking at basic ADL’s when compared to IADLs. There are standardised outcome measures in which to assess IADLs, yet the specific activities needed to enable independence vary depending on the environment and social aspects of the patient's life. It is therefore important to have a grasp of what the patients’ needs to be able to do to remain independent and them review these activities[69]. Functional dependence should be assessed as there are correlations between dependence and increased length of stay in hospital[68].

|

|

Outcome measures

Outcome measures may be useful to assess the patient's ability but also to track the patient’s progress[70][71]. There are many different outcome measures to choose in this population. Some were specifically designed for frailty, while others were developed for other conditions but have been shown to have good psychometric properties with this population. The next section will review some commonly used outcome measures. However, this is not an exhortative list and will not necessarily be the best to use with each patient. It is up to the clinician to select the most appropriate measure for their practice.

| Outcome Measures (OM) |

Description of OM |

Psychometric properties |

|---|---|---|

| Frail elderly functional assessment (1995) |

|

|

| Ten Meter walk test |

10 Metre Walk Test |

|

| The Edmonton frail scale |

12 questions related to cognition, general health status, mobility, social status, medication use, nutrition, mood, continence and functional performance. It has a total score of 17 which depicts severe frailty. It is a very brief way of assessing for frailty and can be used to see whether a CGA should take place[76]. |

|

| PRISMA 7 |

A questionnaire devised of seven yes/no questions that can be used when the patient is unable to carry out a stand up and go or a 10 meter walk test [77]. It was developed with a service in Canadian healthcare, to integrate frailty assessment and management and allow for increase patient-centred care[78]. |

Using this approach can reduce hospitalisation and is an encouraged approach across systems[78]. Its use is recommended by the BGS and can indicate frailty. [28] |

| The Barthel index |

It measures the patients’ ability to look after themselves by asking 10 questions and answers that are graded on the amount of assistance needed to carry out the activity. |

The interrater reliability of this outcome is fair to good depending on which activity is being assessed [79]. |

| Tinetti |

The Tinetti is a 17 item OM used to assess gait and balance[80]. |

|

| Elderly Mobility Scale |

Assesses mobility in the frail by answering 20 questions[85]. |

Good concurrent validity, discriminant validity and inter-rater reliability[86]. |

Both the Edmonton frail scale and the PRISMA 7 can be used by physiotherapists to determine whether a patient who displays symptoms of frailty is frail or not. If a positive result is found, they could refer a patient back to their GP for further assessment [28].

Challenges

|

|

Assessing frail elderly patients can be challenging as a thorough assessment can take a long time. List a few reasons why this may be the case. This should take 5 minutes. |

Why assessments might be time cosuming:

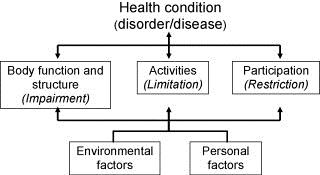

- A thorough top to toe assessment needs to be done including all elements of the ICF model[57] [58][61].

- Are there any cognitive issues present? These include dementia and long-term or short-term memory problems. Cognitive function in the elderly has been shown to have a strong association with reduced functional performance[87]. It can also impact on how you carry out your assessment and communicate with the patient[88][89].

- Auditory problems, affecting the patients’ ability to hear you[48]

- Visual problems, meaning the patient cannot see you or what you are trying to get them to do clearly[48].

- Easily fatigued, causing patients to have reduced performance in activities which occur at the end of the assessment. This may skew the results of any outcome measures used[90].

- Reduced / slow mobility (i.e. Sit-stand takes longer)[90].

| Key points to take |

|---|

|

|

|

|

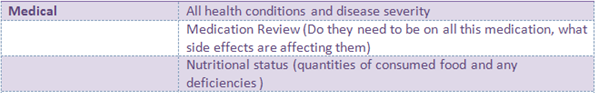

Medical[edit | edit source]

Here is a recap of the Medical section of the CGA:

Health Conditions

Chronic health conditions are common in the elderly. These include, heart disease, arthritis, lung conditions and kidney and liver dysfunction. The body changes as ageing occurs; heart rate decreases, blood vessels and arteries stiffen. This means the heart has to work harder to pump the blood to the body, leading to chronic cardiovascular disease. Bone minerals decrease, reducing their density, muscle strength also declines. Both of these can lead to balance dysfunction, osteoporosis and fractures.

It is out of the scope of this learning resource to go into depth about different health conditions that are prevalent in the frail population. However, we have provided additional reading if you wish to know more.

|

Age UK-A list of common health conditions within the elderly population. Identifying what condition it is, the cause and the symptoms. Aging Society – Identify the meaning of chronic conditions, listing the most common chronic conditions by age, gender and race. |

Medication

Common medication and their side effects

Analgesia[91]:

| Medication | Conditions used to treat | Common side effects | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non- opoid analgesics (Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs) |

Mild to moderate pain | Minimal side effects, High dose can cause liver damage. | Paracetamol, Aspirin, ibuprofen |

| Compound Analgesics | Mild to moderate pain, often as an addition to NSAIDs | Nausea, loss of concentration, constipation | Co-codamol, co- codaprin, co-dydramol |

| Opioid analgesics | Moderate to severe pain. | Impaired balance, nausea and vomiting, constipation, drowsiness and dizziness | Codeine, tramadol morphine |

Other Medication:

| Medication | Conditions used to treat | Common side effects | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta Blockers[92] | Angina, Heart failure, Atrial fibrillation and Heart attach | Dizziness, tiredness, blurred vision, slow heartbeat, impaired balance | Atenolol, bisoprolol, acebutolol, metoprolol |

| Antidepressants[93] | Depression | Dizziness, Impaired balance, Slow reaction, headaches, loss of appetite, anxious, feeling agitated, blurry vision |

Duloxetine, venlafaxine, mirtazapine, amitriptyline, imipramine, Psychotropic, lithium. |

| Benzodiazepines[94] | Relief of severe anxiety | Drowsiness, difficulty concentrating, headaches and vertigo | Diazepam, lorazepam, Chlordiazepoxide |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers[95] | High blood pressure | Dizziness, Confusion, muscle cramps and/or weakness, faintness | Azilsartan, Candesertan, Eprosartan, Losartan |

|

Diuretics[96] |

Water retention, high blood pressure and heart failure |

Nausea, dizziness, muscle cramps |

Thiazide: Chlorothiazide, indapamide.Loop: Bumetanide, furosemide. Potassium-sparing: Amiloride, eplerenone |

| Anticoagulants[97] | Prevent blood clot | Haemorrhage (Excessive bleeding), Dizziness, headaches. | Apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban |

Side effects of medication such as drowsiness, blurred vision and insomnia can interfere with the treatment session and also delay any recovery, it is therefore important for physiotherapists to know if the patient is on any medication to modify treatments.

Polypharmacy is the use of multiple medications and is often unavoidable as the elderly population are more likely to have several co-morbidities. Polypharmacy introduces drug interaction, this can be harmful, as when combined some medications increase the risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

ADRs can become a vicious cycle where more drugs are needed to treat the ADRs for new drugs. Which can result in increased numbers of unnecessary and potentially harmful medications. The physiotherapist can help preventing polypharmacy and the vicious cycle by recognising changes in the patients respond to their drug therapy. It is therefor highly important for physiotherapists to have knowledge and understanding on common medicine and their adverse side effects.

Nutritional status

Nutrition is important for these patients and it should be part of the physiotherapist subjective assessment to check what and how often the patient is eating[53]. The physiotherapist can then reinforce good eating habits and if needed refer the patient to a dietician. It is also important to have an idea about how much the patient eats as this could contribute to increased fatigue. A reduced tolerance to activity is present in frail patients [90] and so how much you include in your first assignment is crucial.

|

|

Drug- related falls in older patients – Going through the implicated drugs, the consequences and possible prevention strategies.

with elderly patient in primary care |

Mental health[edit | edit source]

Here is a recap of the Mental health section of the CGA:

Although it is not the prime role of a physiotherapist, in order to provide a holistic service, we must be aware of and understand the mental health of our patients and the impact that this may have on the individual and their ability to carry out any treatments.

Mental health disorders can be classified as functional or organic[98]

Organic

Age-related cognitive decline is inevitable[99], however, some conditions common amongst older adults can have dramatic effects on cognition[100]. Organic disorders are usually caused by disease affecting the brain, for example, dementia or delirium. Table 1 compares age-related cognitive decline with the early signs of dementia.

| Early signs of dementia | Normal ageing |

| Forgetting things more often than previously, forgetting names of people close to them | Briefly forgetting parts of an experience, forgetting the names of people they rarely see |

| Repeating phrases or conversations | Putting things away incorrectly |

| Unpredictable mood swings | Mood changes appropriately |

| Lack of interest in activities, difficulty making decisions | Changes in their interests |

Dementia

The word dementia describes a set of symptoms that could include memory disorders, personality changes and impaired reasoning. There are various types of dementia, the most common types are Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies[102]. The likelihood of developing dementia increases drastically with age and it is thought that 1 in 14 people over 65 suffer from this condition[103]. Due to the progressive nature of the disease, communication will gradually worsen over time.

Delirium

Delirium is a common clinical syndrome categorised by fluctuating cognitive function and disturbed consciousness. It usually develops over 1–2 days, however, it is associated with poor outcomes[104]. Delirium can be hypoactive or hyperactive, occasionally people will display signs of a mixed picture. Hyperactive delirium usually manifests itself as restlessness, agitation and aggression, whereas people with hypoactive delirium present as withdrawn and quiet[105]. It is thought that the prevalence of delirium on medical wards is 20 to 30%, but reporting in the UK is poor and it is expected this figure is underestimated[106]. People who develop delirium are more likely to stay longer in hospital and have more hospital-acquired complications, such as falls[107]. The physiotherapist may be the patient’s first contact with healthcare and they be required to screen for frailty. OPAC have created a delirium toolkit (see additional reading) and recommend the use of the 4AT to do so and any abnormal results should be discussed with the relevant healthcare professionals[108].

What does this mean for physiotherapists?

With any cognitive condition, effective communication may become challenging and prove as a barrier to successful assessment and treatment. Table 2 highlights some tips to tackle this.

| 1. Keep commands clear and concise with one request at a time – “Stand up please” 2. Allow plenty of time for a response before repeating your question. If the patient is still struggling, try rephrasing. 3. Remove distractions – this could include talking, background noise, eye-catching pictures. 4. Use names and explanations where possible – “Your daughter, Ann” 5. Use other forms of communication:

|

Now watch this video which describes effective communication specifically for people with dementia, however, some of this could be applied to anyone with cognitive decline.

| Effective communication and dementia[111] |

Functional:

Functional disorders have a predominately psychological cause and may include conditions such as depression or anxiety[112]

Depression

1 in 5 community-dwelling older adults are thought to suffer from depression[113]. Whilst this statistic is alarming, it has been suggested that older adults are more susceptible to depression as with age they become more exposed to chronic conditions, health concerns and death, particularly of loved ones[114]. Depression comes with a whole range of symptoms and these vary from person to person.

Now watch this video which explores the cause of depression in ageing.

| Depression in ageing[115] |

Anxiety

The most recently published statistics suggest that 17% of older adults suffer from an anxiety disorder[116]. Anxiety has a wide range of physical and psychological symptoms that can have a debilitating effect on an individual’s life; they may be able to complete tasks physically, however, are limited by their mental health. Anxiety disorders are usually treated with medication but alternative therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy and hypnotherapy are also known to be used[117].

What does this mean for physiotherapists?

Lack of motivation is common amongst most older adults, including those with a functional mental health disorder and treatment to tackle this can feature heavily in your physiotherapy treatment plan[118]. This will be discussed in further detail in the motivation section.

Read this for more information on dementia.

NICE guidelines for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of delirium. Read this for evidence-based information on delirium.

Resources developed for clinicians to improve identification and management of delirium - this includes a copy of the 4AT

|

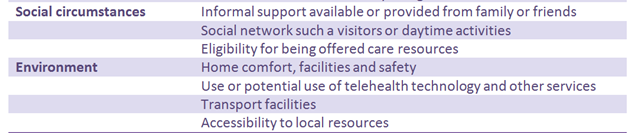

Social and Environmental

[edit | edit source]

Assessment of the social and environmental aspects of a patient’s life is a fundamental part of the CGA, as laid out on section 4.2

Recap of the social and environmental sections of the CGA:

Assessing this type of information is also a key component of the common assessment framework for adults, which was published by the Department of Health [119].

It is an occupational therapists (OT’s) role to devise interventions amend any problems with these. Their assessments and the subsequent home modifications and adaptions can help increase the functional abilities of people who are frail [120]. However, a patients’ ability to carry out activities in the home is dependent on its layout and the persons’ social situation. As physiotherapy interventions try to help improve peoples’ ability to perform ADL’s, it is important for physiotherapists to know how the environment and social situation can impact on their treatment.

The international classification of health, functioning and disability (ICF) can be used by physiotherapists to help establish the needs of the patient[121].

The ICF is a model which allows professionals to see the impact a health condition has on a persons’ life, by taking a holistic viewpoint. Participation restrictions and activity limitations are the two areas of the ICF which relates to the influence of the patients social and environmental circumstances. Activity limitations are the execution of a task by the patient. Whereas, participation restrictions relates to how involved with a life situation the patient is due to the societal setup [121].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has devised a checklist which allows clinicians to identify what activity and participation restrictions the patient has [122].

Social circumstances

[edit | edit source]

Activity limitations

Elderly people who have a high participation level in leisure activities also have better health outcomes. Reduced mobility and activity limitations directly reduce participation in leisure activities. Activity limitations have a bigger impact on social involvement than the severity of the patients’ medical condition. Specific activity limitations which may cause participation restriction are:

• Anxiety [123][124]

• Needing help with personal care[125][124]

• Mobility aid use and walking speed[124][125][126]

• Memory [126][125]

Musculoskeletal impairments cause the majority of activity limitations in elderly community-dwelling adults[127] . Physiotherapists are therefore in a prim position to help reduce activity limitations. A study by Mast and Azar[128] found a correlation between ADL limitations and readmission to hospital in the geriatric population. This shows that physiotherapy targeted at reducing activity limitations could reduce hospital stay as well as improving social network and participation.

Taking a social history

Taking a social history allows the physiotherapist to understand the patient's current level of functioning and their desired functional goals [129][130]. This should include assessment of activities they do in and outside their home and what formal or informal care/support they receive[57][129]. 80% of nonagenarians have carers to help with some of their ADL’s[125]. Having a small amount of regular help with ADL’s may prevent an acute episode turning into an emergency where the patient is no longer safe to stay at home[57]. This shows the importance of knowing the patient's social circumstances.

Environment

[edit | edit source]

Participation restrictions

Elderly people who experience activity limitations sometimes also have participation restrictions[131][125][132] .

Knowing what participation restrictions a patient has is important as they are linked to the patients’ quality of life. Participation frequency should also be noted[131]. It is common for people with frailty who live in the community to report having participation restrictions[48][133]. This is due to reduced community mobility and a reduced ability to carry out work both at home and in the community[48]. Increased participation restrictions are also linked with increasing age[134]. The symptoms of frailty most closely linked to participation restrictions are grip strength, mobility and the number of co-morbidities a patient has[48]. Participation is also linked to environmental factors such as, access to public transport. It has been shown that mobility levels can remain constant even though the patients’ condition may decline[135] .

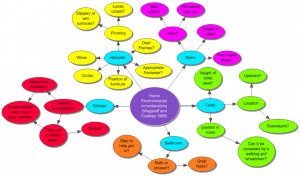

|

The mind map above shows the different things which should be checked in the patients' house on assessment, before a treatment plan is devised or goals are set. Sometimes these assessments are performed jointly with an OT[57].

It is important to know if any intervention is being put in place to help rectify these. Finding out if an OT is involved, what their findings were and what their plan is, is important as then interdisciplinary goals can be devised which are safe and suited to the patient[136]

Being aware of the environment in which the patient lives will allow the physiotherapist to tailor treatments effectively and safely to their surroundings.

Learning activities

|

Answer these questions to test your knowledge in relation to the information presented

|

|

Mr Smith is an 84 year old man who was referred for physiotherapy by Mr Smith had reported “feeling like he cannot walk very far anymore and He was happy for the referral to a community physiotherapist to be made.

Based on this information and what you learned in the section above:

You will be able to read the full case study with the subjective and |

PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENT[edit | edit source]

Having considered the assessment, we will now move on to explore potential physiotherapy interventions in relation to learning outcomes 2 and 3.

As previously mentioned, there are several clinical guidelines available for healthcare professionals to assist them in preventing hospital admissions providing quality care for patients. However, whilst they recommend physiotherapy intervention, these guidelines lack rigorous information and evidence surrounding treatment. This section will summarise and synthesis available evidence on physiotherapy treatment options for preventing hospital admissions in the frail elderly. As there is a lack of evidence available on the effect of physiotherapy in reducing hospital admissions in frail adults, some of the evidence here has been extrapolated from an older adult population and using outcome measures that are thought to reduce likelihood of admission, for example, falls risk.

As two thirds of NHS clients are aged 65 or over[137], there is a plethora of different occasions in which an older person may be admitted to hospital, however it can be loosely split in to two categories: injury and illness [138]. For the purpose of condensing this learning resource and delivering the information you are more likely to need, we will consider the more common admission causes that the physiotherapist can play a part in preventing. However, some of the information provided here could be transferable to other cases.

Injury

[edit | edit source]

Injuries leading to hospitalisation are more common in people over 65 and they can be more critical and more often preventable. The increasing age of the population heightens the significance of this problem[139].

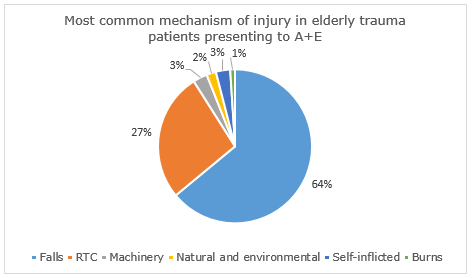

Falls represent the most frequent and serious type of accident in people aged 65 and over in the UK [140]. Gowing and Jain[141] found that a fall is the most common mechanism of injury in elderly trauma patients presenting to accident and emergency units (figure 1) and falls cases are the most common presentation to the Scottish Ambulance Service in the older adult population[142]

|

|---|

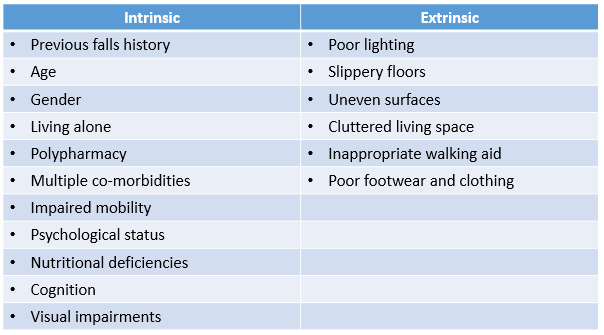

A fall is an incident which results in a person coming to rest unintentionally on the floor or ground or other lower level[143] and can result in fracture, dislocation, traumatic brain injury and even death[144]. Anyone can have a fall, however, the natural ageing process means that older people are at higher risk. Over 400 risk factors leading to falls have been highlighted including muscle weakness, impaired balance, delayed reaction time, poor vision, polypharmacy and co-morbidities such as dementia, cardiovascular disease and hypotension (table 3)[145]. Additionally, several extrinsic factors that could lead to falls have been suggested, including poor lighting, cluttered environment and ill-fitting footwear. The risk of falls and related complications increase gradually with age and can be an indication of increasing frailty[10]. Falls represent the main cause of disability and are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among people over 75 in the UK. Not all falls will result in injury, however in some cases a fall could be fatal and it is thought that the repercussions of even a minor fall could have catastrophic effects on physical and mental health[140].

|

Despite these statistics, falls are not an inevitable consequence of old age. A multifaceted interaction of several risk factors relating to the ageing process, lifestyle choices, environmental factors and the presence of long term conditions determines an individual’s risk of falling[140]. As risk increases with age and it is important for the physiotherapist identify those at risk early, recognise and modify risk factors and provide timely intervention to prevent falls and subsequent injury[146].

A summary of some potential treatment options follows. This list is not exhaustive.

Resistance training[edit | edit source]

A significant component of age-related weakness and frailty is sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is the gradual loss of muscle tissue, resulting in diminished strength[147] and it is thought that 2% of skeletal muscle mass is lost each year past the age of 50[148]. Sarcopenia increases the risk of frailty and falls and in turn, hospitalization in the older adult population[149]. Resistance training has been suggested as a potential treatment for sarcopenia and its prevention. Resistance training is designed to improve muscular fitness by exercising a muscle or a muscle group against resistance[150]. This could lead to improved function, increased quality of life and reduced likelihood for falls[151]. Resistance training programmes have consistently shown to improve muscle strength and mass in older adults[152][153]Seynnes et al 2004), however, it is questionable whether this transfers to reducing the risk of falling.

Latham and colleagues[154] have conducted the only trial which has studied the effect of seated resistance training on risk of falls in an older adult population. This study solely involved home-based, progressive, seated quadriceps strength exercises using 60-80% of the individuals 1RM with ankle weights. It was found to have no effect on falls rate or risk of falling and an increased chance of musculoskeletal injury. As a result, seated resistance training or high intensity resistance are not recommended.

Furthermore, Liu-Ambrose and colleagues[155] examined the effect of a course of 50-minute resistance training sessions, twice weekly for 25 weeks on number of falls and risk of falls in a female population aged 75-85. Exercises included targeted upper limb, trunk and lower limb muscles and again, resistance training alone was found to have no significant effect on number of falls or risk of falls. However, when combined with agility training, participants did develop a decreased risk of falling.

It has been proposed that strength training alone is not enough to fully manage falls risk, however, it should be part of a multi-component falls prevention exercise programme[156]. We will discuss this in further detail later on in the wiki.

Balance re-education[edit | edit source]

Balance disorders are very common in older adults and are a key cause of falls in this population. They are associated with reduced level of function, as well as an increased risk of disease and death. Most balance disorders comprise of several contributing factors including long-term conditions and medication side effects[157].

Recent research conducted examined the effectiveness of two-year progressive balance retraining in reducing injurious falls among community-dwelling women aged 75-85[158]. The study took place over 20 centres and recruited 706 participants who were randomised in to the intervention group, who received weekly dynamic balance exercise supplemented by prescribed home exercise, or the control group, who did not take part in the exercise. Over the two-year intervention period, there were 397 injurious falls in the control group compared with 305 in the intervention group, the injurious fall rate was 19% lower in the intervention group than in the control group highlighting the benefit of a balance training programme.

Exergaming is a relatively new treatment concept and is thought to increase motivation and enjoyment for users.

The Nintendo Wii has a built in pressure sensor that allows for feedback to be delivered to the user on their performance.

There is evidence that a Wii based balance exercise programme could improve balance ability in the frail elderly population[159], so as a result, Fu and colleagues[160] conducted research into whether this would transfer to reducing fall risk and incidence.

Sixty participants aged 65 or over received balance training three times per week for six weeks. They were randomly allocated into the intervention group who undertook balance activity on the Wii, or the control group who received conventional exercise.

The results showed that while both groups reduce their risk and incidence of falls, the intervention group showed a more significant improvement.

The Wii balance training has shown to reduce falls by 69% compared with conventional training. Additionally, the intervention group had a 35% improvement in the fall risk score, considerably greater than that of the conventional balance training at 11%. As a result, the use of the Nintendo Wii for balance re-education is highly recommended and perhaps this suggests the need for further research on various other computer games available.

Exercise aimed at improving balance control has been proven to be a key component in falls prevention. It will be explored further in the multi-component falls prevention programme section of this wiki.

Tai Chi[edit | edit source]

Tai chi is a newly emerging exercise incorporating breathing, relaxation and slow and gentle movements with strengthening and balance exercises. Whilst originally an ancient 13th century Chinese martial art, it has recently become more prevalent around the world as a health-promoting exercise[161]. Whilst there is room for more rigorous research on the health benefits of tai chi, it is thought that it could help adults aged 65 and over in improving balance[162], reducing stress[163] and controlling osteoarthritis pain[164]. Additionally, in a high quality systematic review, tai chi was not only found to significantly reduce rate of falls, but also lessen risk of falls[165]. As tai chi is considered a low impact exercise, it is suitable for most to participate in and should be considered as a treatment option although some may require assistance in locating a suitable local group for them to join.

|

|

Consider these questions:

|

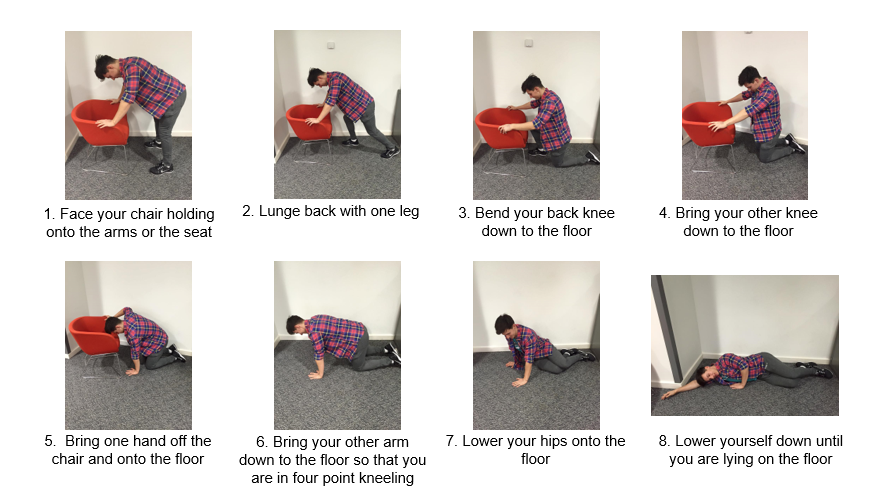

Backward Chaining[edit | edit source]

Declining muscle function in older adults reduces their ability to rise from the floor following a fall and up to a half of all non-injured fallers are unable to get up[167]. When someone is unable to get up off the floor unassisted, the associated risks are far greater due to the complications that can occur from lying on the floor for an extended period of time – for example, dehydration, hypothermia, pneumonia, pressure sores, unavoidable incontinence and even death[168]. This inability to get up has a poor prognosis in terms of hospitalisation and mortality[168], thus, a long lie is one of the most serious consequences of a fall. The responsibility of the physiotherapist is to ensure the patient has a plan should they fall and are unable to rise and educate them about available strategies to combat this[169]

Backward chaining is a method utilised to re-educate patients in rising from the floor unassisted. It consists of a sequence of movements combined together to help teach someone to be able to get down to the floor safely. Once learnt, the sequence is reversed and is applied to teach a safe and effective way to get up from the floor.

The movement is broken into several stages depending on the patient’s ability. The patient will complete one stage, then return to a stand. Then they will add on the next stage and return to a stand. This is repeated until the patient is able to stand from a lying on the floor.

The effect of backward chaining on an individual’s ability to rise unassisted from the ground has been proven to be beneficial. In the only study to compare backward chaining with a control of conventional therapy, it was found that backward-chaining method significantly enhances ability in rising after an incidental fall (20-40%)[171]. The control group showed no improvement. The study took part over 12 weeks and included 120 participants aged 80-99. Additionally, Timed Up and Go and Tinetti measurements were also compared before and after the intervention and control and a notable improvement was only observed from the intervention group. This highlights the benefits for improving functional capabilities in addition to rising abilities.

Fear of falling[edit | edit source]

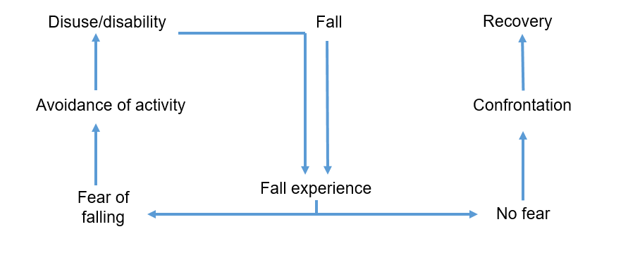

The prevalence of fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults ranges between 12% and 65%[172]. Whilst it frequently occurs after falls[173], it is also established in those without a fall history[174]. It can lead to a loss of independence, activity restriction and ultimately a poorer quality of life[175]. Not all will avoid ADL’s due to fear avoidance but for those who do, it can have debilitating and devastating effects[176]

Lethem et al[177] introduced the psychiatric concept of a fear avoidance model and is it is commonly utilised in the prevention of acute musculoskeletal pain becoming chronic[178]. However, the hypothesis behind the model can be adapted to explain fear of falling and avoidance of activity. Extreme avoidance can lead to a decline in physical function, and ultimately an increased risk of falls, further fuelling fear and avoidance of activities. This is illustrated in the below fear avoidance model, adapted from Lethem et al[177].

The physiotherapist is in an ideal position to steer the individual towards the route of confrontation and recovery as opposed to activity avoidance and disability[146]. There is high quality evidence from two systematic reviews highlighting the benefits of treatment to improve confidence and reduce fear of falling[179][180]. Recommended interventions include: exercise, including tai chi, and multi-component falls prevention programmes.

Multi-component falls prevention programmes[edit | edit source]

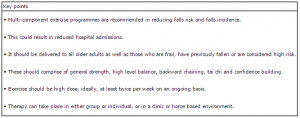

Finally, we will consider the effect of a multi-component falls prevention programme. As most falls are multifactorial in origin, they usually require several interventions[181]. Such interventions typically involve a combination of medication review and optimization and education, environmental modification and exercise. This type of programme would be delivered by a multidisciplinary team in which the physiotherapist would be a key member. A Cochrane systematic review suggests that the physiotherapy treatment should combine all elements mentioned above; that is strengthening, balance, backward chaining, tai chi and confidence building with education, tailored to each individual. Clinic-based group exercise or individual exercise in the home setting is suitable. However, further research is needed into the effectiveness of medication management in preventing falls[165].

Additionally, in a systematic review, it was reported that for the greatest effect, exercise programmes should include a high level challenge to balance, alongside strength and walking training[156]. However, brisk walking training should not be prescribed to those at a high risk of falls. Furthermore, it was found that exercise should not only target those at high risk but the also the general community and it should be performed for at least two hours per week on an ongoing basis.

Learning activity

|

|

|

|

|

Illness

[edit | edit source]

For many people, older age is associated with long term conditions such as heart failure, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and diabetes.

As we know frailty is known as the decreased ability to withstand illness. Exacerbation of chronic conditions, an acute illness or a combination of both can trigger acute disability in frail older people and cause hospitalisation or institutionalisation[27] .

Therefore, this next section will discuss the physiotherapists’ role in promoting self-management of long term conditions and physical activity. Information on how to motivate people for behavior change will also be presented.

Self-management[edit | edit source]

Emergency hospital admissions is a major concern for the NHS. There are a number of factors associated with increased rates of admission including area of residency, ethnicity, socio-economic deprivation and environmental factors. Older people are also identified as being at a higher risk of hospital admittance[47].

In Scotland, 40% of the population have at least one long term condition (LTC). People with LTCs and co-morbidities are known to have poorer clinical outcomes, poorer quality of life and longer hospital stays[182].

The Scottish Government[183] reports that people with LTCs are twice as likely to be admitted to hospital. The aging population and the increase prevalence of long term conditions requires healthcare professionals to move their focus towards preventative strategies and empowering self-management[184].

Disease-related self-management abilities such as taking medication and exercise are often promoted by health care professionals.

However, there may also be a need for interventions aimed at self-management of overall health and well-being to contribute to healthy aging[185]. Older peoples’ abilities to self-manage the aging process depends on physical, psychological and social aspects of their life[186].

Physiotherapists working with frail older people could play a role in promoting healthy aging as evidence shows that interventions to promote healthy aging can be used to the delay the onset of frailty and reduce its adverse outcomes among older people[186].

As older people often have co-morbidities leading to a mixture of physical and psychosocial issues, self-management interventions should focus on providing them with general behavioral and cognitive skills for dealing with range of problems rather than focusing on on health-related problems only[185].

It is out with the scope of this learning resource to go into detail about how to promote self-management strategies as you are likely to see a range of diverse patients presenting with multiple conditions and challenging psychosocial issues. Your treatment plan will depend on the patient's presenting condition. However, as physiotherapists we believe our main role within self-management can be to promote physical activity to contribute to the healthy aging process. Therefore, this will be discussed in more detail in Section 6.2.2 – Physical activity.

Please see additional reading to access useful resources in relation to promoting self-management.

Resources

|

The King’s Fund have published evidence based information on self-management

|

|

Resources for patients

|

Physical activity[edit | edit source]

Functional capacity declines with age and this is further accelerated by low levels of physical activity.

The recommendations for physical activity for older adults (65+)[196]:

- Older adults should aim to be active daily

- At least 150 minutes a week of moderate intensity activity

- Muscle strength training twice a week in addition to the 150 minutes of activity

- Balance training and co-ordination should be incorporated into activities to manage risk of falls

- Minimise sedentary time

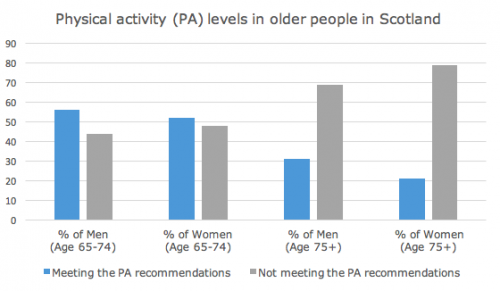

Physical activity significantly decreases with age. The graph below shows the percentage of men and women meeting the physical activity recommendations in Scotland[197].

Benefits of physical activity in frail older adults

Strength, endurance, balance and bone density is lost about 10% per decade, while muscle power reduces with around 30% per decade[198]. Sarcopenia is highly prevalent among older adults and has been identified as a risk factor for frailty[199].

Being physically active slows down these physiological changes associated with aging. Physical activity can also reduce the risk of falls, promote cognitive health and self-management of chronic diseases. As well as slowing down the deterioration in ability to perform ADLs and maintain quality of life in older adults[200][201].

A meta-analysis[200] found that exercise is beneficial to improve balance, gait speed and abilities to carry out ADLs in the frail older adults.

Factors influencing participation in physical activity in older adults[202]

Older peoples’ participation in physical activity can be effected by biological, demographic, physiological and social factors

These factors are important to be aware of when attempting to motivate older people to increase their activity levels.

- Men are more active then women

- A decline in physical activity with age is higher among: minority ethnic groups, those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, those with lower education and those living alone

- Older people might be less able due to pain, reduced mobility and the need of assistance to mobilise[201]

- Physical activity can be influenced by trusted others such as health care professionals, care givers, family and friends

- Lack of transport often affects older peoples abilities to part take in activity

Psychological factors that can positively affect participation

- Beliefs and confidence in abilities to active

- General values, beliefs and attitudes

Psychological factors that can negatively affect participation

- Fear of falling and over exertion

- Safety concerns

Physiotherapists role in promoting physical activity in frail older adults

Due to their training and experience, physiotherapists are in a good position to promote health and wellbeing of individuals and the community through education on physical activity and exercise prescription[203].

Recently there has been a shift in the general public's health agenda towards the prevention of chronic conditions and enabling the aging population to stay active and manage conditions in the community. This has required a change in the role of physiotherapist towards addressing these issues through promotion of physical activity and other lifestyle changes[204].

When encouraging physical activity, physiotherapists should also aim to[205]:

- Identify fears and barriers to being physically active and provide solutions to overcome these

- Provide ongoing support and encouragement

Exercises for frail older adults

These are the recommended activities and intensity for frail older adults to increase physical activity in order to improve general health and well being as well as reduce the risk of falls and manage chronic lifestyle conditions:

- Sessions as short as 10 minutes can provide health benefits[198]

- Frail older adults should aim to accumulate numerous of 10 minute sessions to achieve the recommended activity guides[206]

Suggested activities:

- Take the stairs[196]

- Walking[196]

- Do housework or gardening[196]

- Tai Chi[206]

- Dance[206]

- Swimming[196]

- Home-based or group exercise classes[198]

- Breaking up time spent sitting with short regular periods of standing or walking[206]

- Encourage to move for longer. E.g. Going from moving 5 minutes to 10 minutes may increase the intensity[206]

Did you know?

There is a National Physical Activity Pathway for Secondary Care established to support all healthcare professionals to raise the issue of physical activity, offer simple advice and suggest appropriate activities[207].

| The National Physical Activity Pathway[208] | Providing brief advice[208] |

If you prefer reading about The National Physical Activity Pathway please access the document Physical Activty Pathway in Secondary Care[209].

Resources

|

|

Resources for patients

|

Motivation[edit | edit source]

What is Motivation?

Motivation can be defined as the processes that explains an individual’s intensity, direction and persistence of effort towards

achieving a goal. Motivation often stems from a need we must fulfil and this leads to a specific behaviour[215].

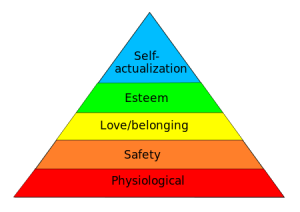

In 1943, Maslow developed a theory of human motivation aiming to explain and rank all types of human needs[216].

Maslow’s Hierarchy model is made up of five levels ranked in importance with the most basic needs at the bottom. In order to progress up the hierarchy the lower needs must be fulfilled.

Depending on your preferred ways of learning, choose if you want to read or watch the video below to learn more about the Maslow’s Hierarchy.

| Read | Watch Video - Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs[217] |

|

Maslow’s hierarchy model is made up of five levels represented in a pyramid with the most basic needs at the bottom working up to the more complex needs. |

What motivates the elderly to exercise?

Shown in the bubbles are some factors that motivate the elderly to participate in exercise programs[218][219].

It is also important to note that within the study conducted by Weeks et al. there was found to be a correlation between those with a previously active lifestyle and those who were more likely to perform exercise programs[218].

How do we motivate?

An article from the Journal of Gerontological Nursing[219] reported that education plays a large role in the motivation, highlighting the benefits of exercise in later years as many older persons will have pre conceived ideas from their younger years. It is also important to allow self-efficacy as this was also found to be motivating to the participant group. This can be achieved through patient centered goal setting.

Muse[220] supports this idea of goal setting within the elderly population. Without goals adherence to exercise is limited. The literature again reinforces the fundamentals of effective goal setting:

• Person centred goals

• Based upon persons objectives

• Small goals to large goals e.g. short term and long term

• SMART

Further to this it is suggested that we must show a willingness to listen to the patient and their needs and that as therapists we can draw upon the benefits of a group exercise class to help motivate the elderly as this gives them not only the physical benefits of exercise but allows them to participate in a social gathering[221].

Resources

|

Use the table in the document to formulate Mr Smith’s:

|

CONCLUSION

[edit | edit source]

You should now be able to...

• Analyse the emerging issue of frailty in relation to the current context of health and social care in the UK.

• Critically evaluate the physiotherapists’ role in the holistic assessment and treatment of frail individuals to prevent hospital admission.

• Evaluate the skills and knowledge gained from this resource; identify appropriate application in clinical practice.