Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

According to a research article in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Legg Calve Perthes is best treated with surgery if the child is eight years old or older at the time of onset; and second if the child falls into a category B or B/C border group of the laterall pillar system (herring).<br>In other studies, good prognosis of a child with this disease under the age of eight has been shown to be up to 80%. This is with minimal treatment given to the patient. In this study, children between the ages of 4 and 5 and 11 months had a less favorable chance of a good outcome. | According to a research article in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Legg Calve Perthes is best treated with surgery if the child is eight years old or older at the time of onset; and second if the child falls into a category B or B/C border group of the laterall pillar system (herring).<br>In other studies, good prognosis of a child with this disease under the age of eight has been shown to be up to 80%. This is with minimal treatment given to the patient. In this study, children between the ages of 4 and 5 and 11 months had a less favorable chance of a good outcome. | ||

== Resources <br> | == Resources <br> == | ||

<u>Books:</u> John Anthony Herring, MD, editors. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease. Rosemont; American Academy of<br> Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996 p. 6-16<br><br><u>Databases:</u> VUBIS catalogus, Pubmed, ScienceDirect, <br> The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery<br><br><u>Websites:</u> http://www.nonf.org/perthesbrochure/perthes-brochure.htm<br><br> http://www.eorthopod.com/content/hip-anatomy<br> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

Revision as of 16:49, 8 January 2011

Original Editor - Pamela Gonzalez, Bahire Evelyne

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases: VUBIS catalogus, Pubmed, ScienceDirect,

The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery

Keywords: Legg-calvé-perthes disease, perthes’ disease, gait, hip range of motion,

atrophy, growth, physical therapy

Timeline: 1975-2010

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD) is an idiopathic juvenile avascular necrosis of the femoral head in children.[1]

The bone death appears in the femoral head due to an interruption in blood supply. As bone death appears, the ball develops a fracture of the supporting bone. This fracture indicates the outset of bone reabsorption by the body. As bone is slowly absorbed, it is replaced by new tissue and bone.[2]

Other names are: ischemic necrosis of the hip, coxa plana, osteochondritis and avascular necrosis of the femoral head.[2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

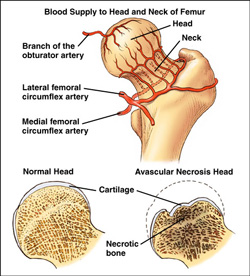

Blood supply to the femoral head: [3]

The femoral head is supplied with blood from the medial circumflex femoral and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, which are branches of the profunda femoris artery.

- The medial femoral circumflex artery:

extends posteriorly and ascends proximally deep to the quadratus femorus muscle.

At the level of the hip it joins an arterial ring at the base of the femoral neck. - The lateral femoral circumflex artery:

extends anteriorly and gives off an ascending branch,

which also joins the arterial ring at the base of the femoral neck.

This vasculare ring gives rise to a group of vessels which run in the retinacular tissue inside the capsule to enter the femoral head at the base of the articular surface.

There is also a small contribution from a small artery in the ligamentum teres to the top of the femoral head which is a branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The origin of Perthes’ disease is unknown, there is consensus however concerning the pathology.

First, there is interrupted blood supply to the capital femoral epiphysis. After this, an infraction of the subchondral bone occurs. Next, revascularization of the area occurs and new bone ossification begins. This is the turning point where a percentage of patients will have normal bone growth and development; while others will develop Legg Calve Perthes Disease. (LCPD). This disease is present when a subchondral fracture occurs. Usually, there is no trauma to cause this scenario. LCPD is most commonly the result of normal physical activity. Because of the subchondral fracture, changes occur to the epiphyseal growth plate.

Classification:

Severity and prognosis of the disease is determined by using a variety of classification systems.

Two of the classification systems are listed here.

The Catteral Classification specifies four different groups to define radiographic appearance during the period of greatest bone loss.

These four groups are reduced down to two by the Salter-Thomson Classification. The first group, which is Group A (Catteral I,II) shows less than 50% of the ball is involved. Group B (Catteral III, IV) shows that more than 50% of the ball is involved. If there is less than 50% involvement the prognosis is good; if there is more than 50% there is usually a poor prognosis.

The Herring Classification is based on the integrity of the lateral pillar of the caput femoris. Group A of this classification shows no loss of height in the lateral 1/3 of the head and little density change. In Lateral Pillar Group B, there is less than 50% loss of lateral height and lucency is present in the joint. In some cases, the ball is beginning to extrude the socket. In Lateral Pillar Group C, there is more than 50% loss of lateral height.

There are four phases of Legg-Calve Perthes Disease which are as follows:

1. Increased density of femoral head possibly leading to fractures

2. Bone undergoes fragmentation and reabsorption

3. Growth of new bone

4. Reshaping of new bone

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

LCP disease is present in children 2-13 years of age and there is a four times greater incidence in males compared to females. The average age of occurrence is six years.

- The limp:

A psoatic limp is typically present in these children secondary to weakness of the psoas major. The limp:[4] is worse after physical activities and improves following periods of rest. The limp becomes more noticeable: late in the day, after prolonged walking, …

- The pain: [4]

The child is often in pain during the acute [1]. The pain is usually worse late in the day and with greater activity.[4] Night pains is frequent.[4]

- ROM:

The child will show a decrease in extension and abduction active ranges of motion. There is also a limited internal rotation in both flexion and extension in the early phase of the disease [5]

- Unusual high activity level: [6]

Children with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease are usually, physically very active, and a significant percentage has true hyperactivity or attention deficit disorder.

- Abnormal growth patterns: [7]

General pattern:

The forearms and hands are relative short compared to the upper arm. [8]

The feet are relatively short compared to the tibia. [8]

Stature low-normal

Severe delays are related to bilateral disease.

Local pattern:

There is an anteversion asymmetry, the affected hip is very often the more anteverted and

the opposite femur has an anteversion pattern different from normal.

There is usually no traumatic event to initiate symptoms

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Listed are some other disorders that should be included in the differential diagnosis for LCPD:

- Septic arthritis-This is an infection in the joint

- Sickle cell-Osteonecrosis of the hip can be a result of this disease

- Spondyloepiphyseal Dysplasia Tarda-This disease typically affects the spine and the larger more proximal joints

- Gaucher’s Disease- This is a genetic disorder that often times includes bone pathology

- Transient Synovitis-This is an acute inflammatory process and is the most common cause of hip pain in childhood

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

A MRI is usually obtained to confirm the diagnosis; however x-rays can also be of use to determine femoral head positioning.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Lower Extremity Functional Scale is one that measures how this disease is affecting the child in a functional way. Since this questionnaire does ask about certain activities the child may not be allowed to perform (i.e. running, hopping, etc), it may not be the outcome measure of choice. The Harris Hip score is another questionnaire that has more to do with a lower level of functional activities such as walking, stair climbing, donning/doffing shoes, sitting, etc. Questionnaires that test the patient on a functional level are useful to provide a baseline and monitor functional progress in the patient’s activities.

Examination[edit | edit source]

1. The limp:

The limp is usually antalgic.[4]

It is possible that the child has a Trendelenburg gait (a positive Trendelenburg test on the affected side) which is marked by a pelvic drop on the unloaded side during single stance. [9]

The child can also have a Duchenne gait, which is marked by a trunk lean toward the stance limb with the pelvis level or elevated on the unloaded side. [9]

2. Range of motion: [4]

The restriction of hip motion is variable in the early stages of the disease;

Many patients, may only have a minimal loss of motion at the extremes of internal rotation and abduction.

At this stage there usually is no flexion contracture.

Loss of hip ROM in patients with early Perthes’ disease without intra-articular incongruity is due to pain and muscle spasm. [10]

This is why, if the child is examined for instance after a night of bed rest, the range will be much better then later in the day.

Further into the disease process;

Children with mild disease may maintain a minimal loss of motion at the extremes only and thereafter regain full mobility.

Those with more severe disease will progressively lose motion, in particular abduction and internal rotation.

Late cases may have adduction contractures and very limited rotation, but the range of flexion and extension is only seldom compromised.

3. Pain: [4]

Pain occurs during the acute disease.[1] The pain may be located in the groin, anterior hip area, or around the greater trochanter. Referral of pain to the knee is common.

4. Atrophy: [4]

In most cases there is atrophy of the gluteus, quadriceps[10] and hamstring muscles, depending upon the severity and duration of the disorder.

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Medications include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs) for pain and/or inflammation.

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

There is no consensus concerning the possible benefits of physiotherapy in LCP disease, or in which phase of the development of the health problem it should be used.

Some studies mention physiotherapy as a pre- and/or postoperative intervention, while others consider it a form of conservative treatment associated with other treatments, such as skeletal traction, orthesis, and plaster cast.

In studies comparing different treatments[12], physiotherapy was applied in children with a mild course of the disease. The characteristics of the patients were:

- Children with less than 50% femoral head necrosis (Catterall groups 1 or 2) [12]

- Children with more than 50% femoral head necrosis, under six years, whose femoral head cover is good (>80%)[12]

- Herring type A or B[13]

- Salter Thompson type A[13]

For patients with a mild course, physiotherapy can produce improvement in articular range of motion, muscular strength and articular dysfunction(meaning?....)[13]. The physiotherapeutic treatment included:

- Passive mobilisations for musculature stretching of the involved hip.

- Straight leg raise exercises, to strengthen the musculature of the hip involved for the flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction of muscles of the hip.

- They started with isometric exercises and after eight session, isometric exercises.

- A balance training initially on stable terrain, and later on unstable terrain.

For children over 6years at diagnosis with more than 50% of femoral head necrosis, proximal femoral varus osteomy gave a significantly better outcome than orthosis and physiotherapy[12].

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

According to a research article in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Legg Calve Perthes is best treated with surgery if the child is eight years old or older at the time of onset; and second if the child falls into a category B or B/C border group of the laterall pillar system (herring).

In other studies, good prognosis of a child with this disease under the age of eight has been shown to be up to 80%. This is with minimal treatment given to the patient. In this study, children between the ages of 4 and 5 and 11 months had a less favorable chance of a good outcome.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Books: John Anthony Herring, MD, editors. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease. Rosemont; American Academy of

Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1996 p. 6-16

Databases: VUBIS catalogus, Pubmed, ScienceDirect,

The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery

Websites: http://www.nonf.org/perthesbrochure/perthes-brochure.htm

http://www.eorthopod.com/content/hip-anatomy

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

- ↑ Herring JA, Kim HT, Browne R. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease Part II: Prospective Multicenter Study of the Effect of Treatment on Outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2004;86:2121-2134.fckLRComputer File.

- ↑ Wheeless’ Textbook of Orhthopaedics. Legg Calve Perthes Disease. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/legg_calve_perthes_disease(accessed 6/21/09).

- ↑ Emedicine. Legg-Calve Perthes Disease. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/826935-overview (accessed 6/21/09).

- ↑ Rosenfeld SB, Herring JA, Chao JC. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease: A Review of Cases with Onset Before Six Years of Age. J Bone Joint Surg Am.2007;89:2712-2722.fckLRComputer File.

- ↑ National Osteonecrosis Foundation. Legg-Calve Perthes Disease. http://www.nonf.org/perthesbrochure/perthes-brochure.htm (accessed 6/16/09).