Lower Crossed Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Search Strategy == | == Search Strategy == | ||

Revision as of 22:18, 19 January 2013

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

A way of finding information about an Unterkreuz syndrome is visiting databases such as PubMed and Web of Knowledge and reading books in the library.

The keywords or combinations of the keywords that were most successful were: lower crossed syndrome, lower pelvic syndrome, distal crossed syndrome, muscle imbalance syndromes,…

Search Timeline: October, 2012 - December, 2012

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

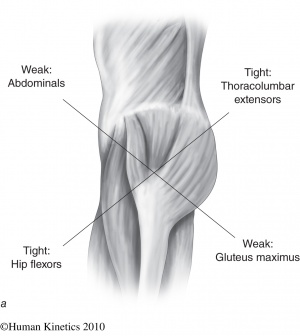

The ‘Unterkreuz syndrome’ is also known as pelvic crossed syndrome, lower crossed syndrome or distal crossed syndrome. The lower crossed syndrome (LCS) is the result of muscles strength imbalances in the lower segment. This syndrome, along with the upper crossed syndrome and layer syndrome, is characterized by specific patterns of muscle weakness and tightnes that cross between the dorsal and the ventral sides of the body. So tightness of the thoracolumbar extensors on the dorsal side crosses with tightness of the iliopsoas and rectus femoris on the ventral side. Weakness of the deep abdominal muscles on the ventral side crosses with weakness of the gluteus maximus and medius. The hamstrings are frequently found to be tight in this syndrome as well.[1]

Figuur 1: lower crossed syndrome [1]

Classification:

Muscle Strength: is the amount of force a muscle can produce at maximum exertion. Resulting from the muscle imbalance the muscle strength will decrease.

Muscle weakness: is a lack of muscle strength.

Muscle tightness: refers to the muscle tone, muscle tension.

Muscle balance: Human movement and function requires a balance of muscle length and strength between opposing muscles surrounding a joint. Normal amounts of opposing force between muscles are necessary to keep the bones centered in the joint during motion.

Muscle imbalance: occurs when opposing muscles provide different directions of tension due to tightness or weakness. When a muscle it too tight, the joint tends to move in that direction and is limited in the opposite direction. The muscles follow ‘the path of least resistance.’ [1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

In lower crossed syndromes the muscles weaken and others shorten in response to stress (overuse, misuse, abuse). This causes are patient-dependent. It is the patient’s history that should provide this information.

To find out what the main cause is, you can ask about the patient’s postural history of constrained postures from repetitive tasks and sedentary lifestyle. [3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The pelvic crossed syndrome involves the trunk muscles. They consist of:

• The abdominals (rectus abdominus, obliques internus & externus abdominus, transversus abdominis)

• The back muscles (erector spinae, multifidus , quadratus lumborum and lattisimus dorsi)

• The gluteals (gluteus maximus, medius and minimus)

function: bring the hip up and leg out

• The hip flexors (iliopsoas en tensor fasciae latae)

function: bending the hip up

• The hamstrings

function: bringing the hip backwards

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

This muscles imbalance creates joint dysfunction (ligammentous strain and increased pressure particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, the SI joint and the hip joint), joint pain (lower back, hip and knee) and specific postural changes (lower back, hip and knee), such as: anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, external leg rotation and knee hyperextension. But it also can lead to changes in posture in other parts of the body, such as: increase thoracic kyphosis and increase in cervical lordosis. [4] [6]

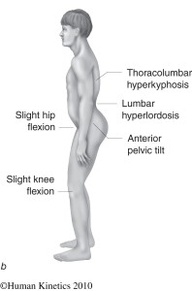

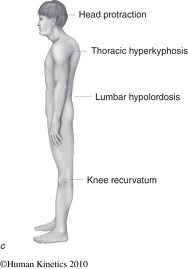

There are two subtypes (A &B) of lower crossed syndrome. The two types are similar and involve the same main muscle imbalance characteristics. For type A the imbalance manifests mainly in the hip, while for type B the imbalance mainly manifests in the lower back.

- Type A: Because the hip flexors are shortened, the pelvis is tilted anteriorly and the hip and knee are in slight flexion. This gives an expression for the compensatory hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine and hyperkyphosis in the transition from thoracic to lumbar spine.

- Type B: here are the abdominal muscles too weak and too short. The compensation is reflected by a minimal hypolordose of the lumbar spine, a hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine and protraction of the head. The anterior pelvic tilt and knees are in hyperextension. [1] [2]

Figuur 2: type A [1]

Figuur 3: type B [1]

Examination[edit | edit source]

OBSERVATION IN ERECT STANDING AND GAIT [2]

- look at the position of the pelvis. You will notice an increase of anterior tilt of the pelvis. This can we associated with increased lumbar lordosis.

- Next the shape, size and tone of the tightened/inhibited muscles. (see Definition/Description)

ACTIVE EXAMINATION : [2]

Hip extension - is examined to analyze the hyperextension phase of the hip in gait. Use a straight leg lifting.

Hip abduction –the patient with LCS, will combine the abduction with an lateral rotation and a flexion of the hip.

Trunk curl up – is tested to estimate the interplay between usually strong iliopsoas and the abdominal muscles.

Figuur 4: Hip Abduction [2]

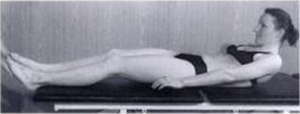

Figuur 5: Trunk Curl up [2]

PASSIVE EXAMINATION : [2]

Hipflexors are tested with the patient in a modified Thomas position. This test can be influenced by the stretch of the joint capsule and thus more specific test should be performed to confirm the tightness of the adductors. Confirmation of tightness is clear when excessive soft tissue resistance and decreased range of motion are encountered on application of pressure in the following directions.

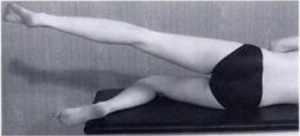

The tightness of Hamstrings are tested with a straight leg test.

Thigh adductors are tested with the patient lying supine at the edge of the plinth. Tight hamstrings may contribute to the range limitation. If this situation occurs, bending the knee should increase the range of movement.

The piriformis muscle is tested with the patient in a supine position. At the end of the range of motion do you notice a soft and gradually increasing resistance. If the muscle is tight, the end feel is hard and may be associated with pain deep in the buttocks.

Quadratus lumborum is difficult to examine. In principle, passive trunk side bending is tested while the patient assumes a side-lying position. The reference point is the level of inferior angle of the scapula. A simpler screening test entails observation of the spinal curve during active lateral flexion of the trunk.

Spinal erectors are also difficult to examine. As a screening test, forward bending in a short sit allows observation of the gradual curvature of the spine.

Triceps surae are tested by performing passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Normally, the therapist should be able to achieve passive dorsiflexion to 90 degrees.

Physical Therapy management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of tightness is not in strengthening, which would increase tightness and possibly result in more pronounced weakness, but in stretching, oriented toward influencing the noncontractile but retractile connective tissue of the muscle. Stretching of tight muscles also results in improved strength of inhibited antagonistic muscles, probably mediated via the Sherrington’s law of reciprocal innervation.

(grades of recommendation: C) [3] [5]

The solution for these common patterns is to identify both the shortened and the weakened structures and to set about normalizing their dysfunctional status. This might involve:

• deactivating trigger points and removing muscular adhesions. Perform myofascial release and trigger-point massage to the gluteus muscles, iliopsoas and tensor fasciae latae.

(grades of recommendation: B) [7]

• Laser or ultrasound therapy on the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae.

• Regaining the normal lumbar flexion mobility

• normalizing the short and weak muscles, with the objective of restoring balance. This may involve purely soft tissue approaches (stretching the short muscles) or be combined with chiropractic adjustment mobilization of the sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine.

• Core stabilization exercises to strengthen the abdominal muscles.

• reeducation of posture and body usage.

(grades of recommendation: C) [3] [5]

References[edit | edit source]

Books: (library Jette & Etterbeek)

[1] Page P., C. Frank C., Lardner R., (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: The Janda approach, human kinetics. (Chapter 4 p. 43-56)

[2] Liebenson C., (1996). Rehabilitation of the spine: a practitioner’s manual, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (p. 232-235)

[3] Chaitow L., DeLany J.W., (2002). Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques: the lower body: Churchill livingstone. (p.26,36)

[4] Joseph J. Cipriano, (2010). Photographic manual of regional orthopaedic and neurologic tests: Wolters Kluwer (p.27-28)

Internet:

[5] Nickelston P. Lower crossed syndrome and knee pain: Dynamic Chiropractic, 2007, Volume 25, issue 11. (level of evidence: 5)

[6] Sweeting K., Mock M. Gait and posture: assessment in general practice: Australian Family Physician, 2007, Volume 36, issue 6. (level of evidence: 3B)

[7] Simons D.G., Understanding Effective Treatments of Myofascial Trigger Points: Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 2002, Volume 6, issue 2. (level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Page P., C. Frank C., Lardner R., (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: The Janda approach, human kinetics. (Chapter 4 p. 43-56)