Opioids: Difference between revisions

Justin Bryan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Justin Bryan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

===== Recognizing Opioid Misuse ===== | ===== Recognizing Opioid Misuse ===== | ||

Identifying patients who may be experiencing opioid misuse can be as simple as being alerts for certain behaviors, practices, or actions observed or voiced during a physical therapy session. Below are some common signs that if notices may be reason for further inquiry with your patient. | Identifying patients who may be experiencing opioid misuse can be as simple as being alerts for certain behaviors, practices, or actions observed or voiced during a physical therapy session. Below are some common signs that if notices may be reason for further inquiry with your patient.<ref>Mayo Clinic. How to tell is a loved one is abusing opioids. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prescription-drug-abuse/in-depth/how-to-tell-if-a-loved-one-is-abusing-opioids/art-20386038</ref><ref>Johns Hopkins Medicine. Opioid Use Disorder. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/opioid-use-disorder</ref> | ||

* Non-indicated use - | * Non-indicated use - taking more than a prescription calls for at a given time or taking the medication for the feeling it elicits | ||

* Preventative use - a patient may report using an opioid "just in case" or continued use when pain is not present | * Preventative use - a patient may report using an opioid "just in case" or continued use when pain is not present | ||

* Changes in mood or mood patterns, | * Changes in mood or mood patterns, or behaviors of isolation | ||

* Changes in sleep (sleeping more or less than usual) | |||

* Drowsiness, malaise, weight loss, or sexual changes | |||

* Altered routines or habits with no other apparent cause | |||

* "Borrowing" medication or "loosing" a prescription to attain a refill | * "Borrowing" medication or "loosing" a prescription to attain a refill | ||

* Redundant prescriptions - seeking additional or backup prescriptions from multiple doctors | * Redundant prescriptions - seeking additional or backup prescriptions from multiple doctors | ||

* Decreased inhibition, poor decision making, reckless or dangerous actions or choices | * Decreased inhibition, poor decision making, reckless or dangerous actions or choices | ||

{{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bp2lhI4ka4M|width}} | {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bp2lhI4ka4M|width}} | ||

Opioid use is also linked to increased [[falls]] | ===== Opioids, Falls, and Chronic Pain ===== | ||

Opioid use is also linked to increased risk of [[falls]]. A 2018 retrospective cohort study by Daoust et al. found an increased risk of falls, as well as higher incidence of death from fall-related injuries, in older adults who reported recent opioid use. Results also showed that opioid use was associated with increased length of stay in hospitals for treatment of these injuries. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYrQUj2yecs&app=desktop|width}}<ref>Fox 47 news. Opiod use linked to increased risk of falls. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYrQUj2yecs&app=desktop (last accessed 9.4.2019)</ref> | {{#ev:youtube|https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYrQUj2yecs&app=desktop|width}}<ref>Fox 47 news. Opiod use linked to increased risk of falls. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYrQUj2yecs&app=desktop (last accessed 9.4.2019)</ref> | ||

Revision as of 19:51, 20 February 2023

Introduction[edit | edit source]

An opioid (exogenous opioid) refers to any substance from a group of analgesic agents derived from the ingredient opium. Opioids are a type of depressant, analgesic drug that slows down the messages being sent through the central nervous system between the body to the brain. Although used to treat pain, opioids can entice euphoric feelings and sedative effects which can be addictive, which makes abuse of this drug group increasingly common.

Opioids can be naturally occurring, synthetic, or semi-synthetic depending how they are derived. Natural and semi-synthetic opioids utilize substances extracted from opium, which is produced from the dried seeds of the opium poppy. Fully synthetic opioids, on the other hand, are derived using laboratory methods to produce the same compounds naturally found in opium through controlled chemical processes. A least 20 different compounds are found in opium; these biologically active substances can either produce analgesic effects directly (i.e. morphine), or act as precursors that can be used to produce other analgesic drugs including semi-synthetic opioids.[1]

Clinical Pharmacology[edit | edit source]

Production of opioids begins with four naturally occurring alkaloids which can be isolated from the opium poppy seed (papaver somniferum). These plant-derived amines, which include morphine, codeine, papaverine and thebaine, can then be used to produce many varieties of semi-synthetic opioids useful in clinical medicine. Common semi-synthetic opioids derived from these four substances include diamorphine, dihydrocodeine, buprenorphine, nalbuphine, naloxone and oxycodone.[2]

Opioids exert their analgesic properties by binding to specialized "opioid" receptors that already exist on the neurons at specific sites in the central nervous system. These receptors exist in concert with endogenous (produced by within the body) opioid-like substances, both of which act as part of the body's natural process of controlling pain and inflammation. The three groups of endogenous opioid-like substances include endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins. In addition to pain control, endogenous opioid-like substances are believed to play a role in other processes including response to stress, immune modulation, GI function, eating and others.[1]

Opioid Receptors[edit | edit source]

There are three major types of opioid receptor, 𝜇, 𝛿, and 𝜅 (mu, delta and kappa), found throughout the body. Other opioid receptors do exist, i.e. nociceptin/orphanin FQ peptide receptors, however no know exogenous opioid has been found to specifically act upon them. As such, opioids are commonly classified by their ability to exert an effect by binding to one of the three main receptors (𝜇, 𝛿, and 𝜅). All 3 receptors will produce analgesia when binded with an opioid substance, but the degree of effect is determined by how strongly a given opioid binds to a given receptor. This degree of "affinity" produces further sub classifications under each receptor type.[1][2]

Of the three opioid receptor types, each produces analgesic effects when a substance binds to it. That being said, each receptor type a produce unique and distinct spectrum of impacts when activated. This specificity can be useful in choosing a specific opioid to target a patient's unique symptoms. Common unique effects of each receptor are listed below:[1]

- Mu (𝜇) - Sedative effects, depression of respiratory function, constipation, reduction in release of neurotransmitters

- Delta (𝛿) - Sedative effects, constipation, psychoactive effects

- Kappa (𝜅) - Heightened release of hormones, reduction in release of neurotransmitters

Opioid Mechanisms of Action[edit | edit source]

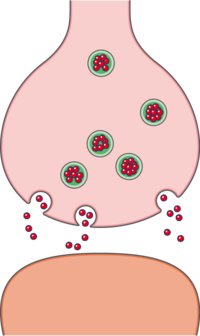

Opioids produce their analgesic effect by acting directly on the synapses of neurons in the brain, spinal cord, and other tissues of the body. Each of these three areas are unique in their characteristics and how opioids specifically exert their effect.[1]

- Spinal Cord: Opioid action at the level of the spinal cord impacts the transmission of pain signals from peripheral nerves to the brain. This occurs mainly by through the binding of presynaptic receptors of pain neurons, resulting in a reduction of the release of pain-mediating neurotransmitters including Substance P.

- Brain: Opioid action in the brain occurs by altering the action of neurons responsible for interpretation and transmission of pain signals. A common belief is that opioids facilitate increased activity of descending pain pathways by blocking the signals of interneurons that would typically inhibit these pathways. When this process occurs it is known as disinhibition. At the same time, increased descending pathway activity also blocks the transmission of pain signals in the spinal cord through the same mechanism as opioids acting on this region.

- Peripheral Tissue: Opioid receptors have been found on peripheral sensory neurons, allowing opioids to act directly in these areas. When the receptors on these peripheral nerves are bound by opioids, the excitability of the neurons in reduced. In this way, analgesia is achieved preventing pain signals from even being produced.

Categories of Opioid Drugs[edit | edit source]

Opioids are classified based on the characteristics of how they bind to opioid receptors in the body. Specifically, these classification are heavily influenced by the strength or affinity to which an agent binds. Additionally, the specification of agonist versus antagonist is an important distinction. Agonist agents are defined by their ability to bind and activate opioid receptors. Antagonist, on the other hand, still bind these receptors, but they activate the opioid receptors only mildly or even not at all.[1]

- Strong Agonists: The main use of strong agonist opioids is in the treatment of severe pain. These opioids bond very strongly to receptors, primarily Mu (𝜇) receptors in the brain and spinal cord. Common strong agonist opioids include: Morphine, Fenanyl, Meperidine, and Methadone.

- Mild-to-Moderate Agonists: Mild-to-moderate agonists bond strongly to opioid receptors, but to a lesser degree than strong agonists. This results in reduced efficacy as well as effect of these agents. As such, this category of opioids is generally indicated for moderate pain. Examples include: Codeine, Hydrocodone, and Oxycodone.

- Mixed Agonist-Antagonist: The category is defined by the phenomenon by which these agent act both as agonists (bind and activate) for certain opioid receptors, and antagonists (bind and don't activate) for other receptors. This characteristic can be useful in that these drugs can be used to achieve analgesia with fewer side effects. One example is the opioid is butorphanol, which is a agonists for Kappa receptors and an antagonist for Mu receptors. The effect of this combination is the achievement of analgesia (activation of Kappa receptors) with a reduction in the risk of respiratory depression (blocking of Mu receptors). Of particular note, while mixed agonist-antagonists generally carry less of a risk dangerous side effects as well as dependency, they do carry a higher risk for psychotropic side effects such as hallucinations.

- Antagonists: Pure antagonist opioids carry no analgesic properties due to their ability to bind receptors, but not activate them. As such, when antagonists bind opioid receptors, they block other opioids from also binding. These characteristics make them ineffective in pain management, however they are an important aspect of opioid management for use in the treatment of addition and overdose. The most common antagonist drug used in the USA is naloxone.

Benefits & Drawbacks of Opioids[edit | edit source]

Opioids can produce profound analgesia for patients with acute pain. Opioids are very effective at treating acute pain due to their ability to inhibit pain signal transmission at multiple stages in the pain pathway and their ability to enhance the inhibitory pain fibres.

There are many adverse effects associated with opioids. Kappa receptor stimulation is associated with side effects such as hallucinations, dysphoria, anxiety and restlessness. Delta and mu receptor stimulation is often dangerously associated with respiratory depression as the body is unable to regulate carbon dioxide levels in the body effectively. Other drawbacks associated with opioid use in general include sleep apnoea, hypothalamic-pituatory axis supression (hormonal changes with the potential for decreased libido, infertility & fluid retention), urinary retention, nausea & vomiting, physical dependence and addiction, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, dental pathology, constipation, increased mortality and tolerance.[3]

Considerations in Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Prescription of opioids for the management of pain has increased significantly in the last few decades. A large contributor to this increase in the United States was the 2001 initiative from The Joint Commission, an independent group who oversees quality and practice within healthcare, to improve the management of patient's pain. As a result, pain quickly became known as the "fifth vital sign," sparking a dramatic increase in efforts to assess and manage patient's pain. Unfortunately, this heightened emphasis on pain control also lead to an dramatic uptick in the use of pain control medications, specifically opioids. Pharmaceutical companies began to highly promoted these drugs after seeing an opportunity to provide a solution to a "newly recognized" problem. As opioid use increased, so did addiction and abuse of these medications. Between the years 2001 and 2013, opioid overdoses deaths increased at least 5 times in the United States.[4]

Physical therapy can play a vital role in managing what is now considered by some to be an "opioid epidemic." Polling performed by Gallop indicated that in an American sample of 6200 adults, 78% would rather have their pain controlled by drug-free interventions compared to the use of opioids. While the actual follow-through is not this high, these figures highlight a desire by patients to have other options besides opioids for controlling pain, options that can be provided by physical therapy.[4]

A 2018 viewpoint article in the Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy suggested three ways that physical therapists can promote the use of drug free pain management. The first area is education; physical therapists are in a unique position to provide information to both patients, as well as other practitioners, on the availability and effectiveness of therapy in managing both acute and chronic pain. Studies such as the 2018 JAMA study by Krebs, et al. clearly support physical therapy interventions as being at least as effective improving pain related function in conditions such as knee osteoarthritis compared by opioids. Education should also include helping patients to understand pain neuroscience, of the mechanisms of how pain occurs in the body. A 2016 study by Louw et al. showed that simply educating patient with chronic pain on the biological processes causing their pain can significantly reduce their symptom, improve function, and minimize healthcare utilization. The second area the viewpoint addressed was the need to promote early access to physical therapy. Many studies have shown that when physical therapy services are provided early in a patient's course of treatment through aspects such as same-day access clinics or direct access care, a reduction in seen in metrics including cost, healthcare utilization, duration of recovery, and prescription of opioids. The final area addressed was prevention. Physical therapists as practitioners are specifically qualified to address a variety of aspects that contribute to poor health outcomes. Physical therapists interventions often include preventative screening, promoting of improved sleep and nutrition, increased physical activity, and many other aspects that can improve overall quality of life. As such, by addressing these topics, physical therapists can help patients manage or even prevent chronic pain.[4] [5] [6]

Physical Therapy and Patients Prescribed Opioids[edit | edit source]

Opioids are regularly administered for the treatment of pain; many patients that present to physical therapists may have already been prescribed them. This is even more common in those being treated for musculoskeletal pain with opioids being prescribed in these cases as much as 30% of the time. In conjunction with this, as many as 75% of patients exhibiting opioid misuse behaviors report experiencing musculoskeletal pain.

While prescription management is not within the scope of practice for physical therapists, they can still play a vital role in screening for and referring patients who are at risk of opioid misuse. Below are several aspects that physical therapists should be aware of a incorporate into their assessment and treatment patients who complain of pain.[7]

- Inquire about any past or current use of prescription opioids

- Do not judge a patient's use or need for opioids but instead provide constructive guidance and education on safe use

- Monitor for opioid misuse behaviors and discuss these with the patient

- If opioid misuse is suspected, contact the referring physician (if the patient has one) or refer the patient to a an addiction specialist

- Maintain open and non-judgemental communication at all time, educating, and guiding them when possible

Recognizing Opioid Misuse[edit | edit source]

Identifying patients who may be experiencing opioid misuse can be as simple as being alerts for certain behaviors, practices, or actions observed or voiced during a physical therapy session. Below are some common signs that if notices may be reason for further inquiry with your patient.[8][9]

- Non-indicated use - taking more than a prescription calls for at a given time or taking the medication for the feeling it elicits

- Preventative use - a patient may report using an opioid "just in case" or continued use when pain is not present

- Changes in mood or mood patterns, or behaviors of isolation

- Changes in sleep (sleeping more or less than usual)

- Drowsiness, malaise, weight loss, or sexual changes

- Altered routines or habits with no other apparent cause

- "Borrowing" medication or "loosing" a prescription to attain a refill

- Redundant prescriptions - seeking additional or backup prescriptions from multiple doctors

- Decreased inhibition, poor decision making, reckless or dangerous actions or choices

Opioids, Falls, and Chronic Pain[edit | edit source]

Opioid use is also linked to increased risk of falls. A 2018 retrospective cohort study by Daoust et al. found an increased risk of falls, as well as higher incidence of death from fall-related injuries, in older adults who reported recent opioid use. Results also showed that opioid use was associated with increased length of stay in hospitals for treatment of these injuries.

Opioids alone are not a solution for chronic pain as supported by an abundance of literature. [11][12][13]

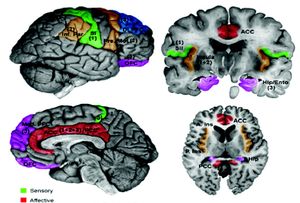

The image below shows the many areas involved in the brain with pain processing.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Ciccone CD, editors. Pharmacology in Rehabilitation. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 2016. p202-218.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pathan, H., & Williams, J. (2012). Basic opioid pharmacology: an update. British journal of pain, 6(1), 11-6.

- ↑ Prescription Opioid Policy. A publication by The Royal Australian College of Physicians, Faculty of Pain Medicine ANZCA, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mintken PE, Moore JR, Flynn TW. Physical Therapists’ Role in Solving the Opioid Epidemic. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2018; 48(5): 349-353.

- ↑ Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016; 32: 332– 355.

- ↑ Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018; 319: 872– 882.

- ↑ Magel J, Kietrys D, Kruger ES, Fritz JM, Gordon AJ. Physical therapists should play a greater role in managing patients with opioid use and opioid misuse. Subst Abus. 2021; 42(3): 255-260.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. How to tell is a loved one is abusing opioids. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prescription-drug-abuse/in-depth/how-to-tell-if-a-loved-one-is-abusing-opioids/art-20386038

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Medicine. Opioid Use Disorder. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/opioid-use-disorder

- ↑ Fox 47 news. Opiod use linked to increased risk of falls. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mYrQUj2yecs&app=desktop (last accessed 9.4.2019)

- ↑ Reinecke H, Weber C, Lange K, Simon M, Stein C, Sorgatz H. Analgesic efficacy of opioids in chronic pain: recent meta‐analyses. British journal of pharmacology. 2015 Jan;172(2):324-33.

- ↑ Manchikanti L, Kaye AM, Knezevic NN, McAnally H, Slavin K, Trescot AM, Hirsch J. Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2017 Feb 1;20(2S):S3-92.

- ↑ Walsh K. General practice pain management: beyond opioids. InBSAVA Congress Proceedings 2016 2016 Apr 1 (pp. 354-354). BSAVA Library.