Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction: Difference between revisions

m (Text replace - 'Category:EIM_Student_Project_2' to 'Category:EIM_Residency_Project') |

Tim Hendrikx (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

Changes in the posterior tibial tendon, ranging from degeneration to rupture, can lead to various symptoms. These symptoms can be classified into the four different | Changes in the posterior tibial tendon, ranging from degeneration to rupture, can lead to various symptoms. These symptoms can be classified into the four different stages of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD). Edwards et al. (level of evidence A) state that PTTD is considered to be the main cause of adult acquired flat foot. <ref name="Edwards et al." /><br> Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) is according to some authors a synonym to adult acquired flatfoot deformity (AAFD). The treatment for both conditions is therefore similar. <ref name="Matthew D. Nielsen et al.">Matthew D. Nielsen, Erin E. Dodson, Daniel L. Shadrick, Alan R. Catanzariti, RobertW. Mendicino, D. Scot Malay. Nonoperative Care for the Treatment of Adult-acquired Flatfoot Deformity. The Journal of Foot &amp;amp; Ankle Surgery. 50 (2011) 311–314. (level of evidence B)</ref> | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | ||

Revision as of 13:31, 30 December 2012

Original Editor - Brian Duffy, Hennebel Lien, Nele Postal

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases searched: Pubmed, Pedro and Web of Knowledge

Keywords searched: Tibialis Posterior, Dysfunction, Examination, Ankle phatology, Review, Randomised Controlled/Clinical Trial, Physiotherapy, PTTD, Acquired flatfoot, Gait, Treatment

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Changes in the posterior tibial tendon, ranging from degeneration to rupture, can lead to various symptoms. These symptoms can be classified into the four different stages of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD). Edwards et al. (level of evidence A) state that PTTD is considered to be the main cause of adult acquired flat foot. [1]

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) is according to some authors a synonym to adult acquired flatfoot deformity (AAFD). The treatment for both conditions is therefore similar. [2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

The posterior tibial tendon runs posterior to the medial malleolus inserting into the navicular tuberosity and the plantar aspect of the tarsus. It is the primary stabilizer of the medial longitudinal arch, aiding in mid and hind foot locking during ambulation. If compromised, a resulting pes planus foot may develop and place greater stress on the surrounding ligaments and soft tissue[3]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Once thought to be a tendonitis, it is now commonly accepted the process is one of tendon degeneration or tendinosis. A poor blood supply has been identified as well as mechanical factors such as peroneal brevis overactivity or a pes planus foot. The latter will gradually place increased stress to the posterior tibial tendon causing early degeneration. Trauma ( ankle sprain, fracture) may also initiate the process[3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

1. Pain/swelling behind medial malleolus and along medial longitudinal arch

2. Change in static/dynamic foot ( pes planus)

3. Limited walking ability

4. Impaired balance

5. Impaired MMT PF/IV

6. Difficulty/inability to perform unilateral heel raise. Limited calcaneal inversion upon ascent

7. Impaired subtalar mobility

Clinical characterizes per class of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: [3]

- Stage I dysfunction: medial ankle pain, a mild swelling, no change in footshape;

- Stage II dysfunction: less pain and swelling, a flattened arch, abducted midfoot, change in footshape, instability;

- Stage III en IV: patients have also pain on the lateral hindfoot.

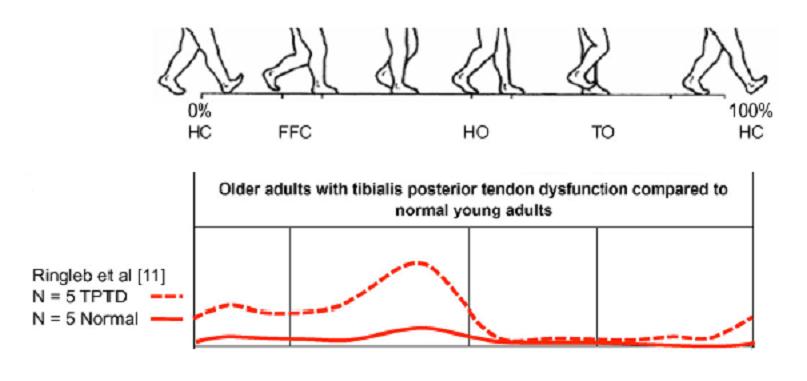

The posterior tibial tendon during gait:

The functions of a healthy tendon are plantar flexion of the ankle, inversion of the foot and elevating the medial longitudinal arch of the foot (it appears as the primary stabiliser of this arch). This elevating of the medial longitudinal arch causes a locked entire of the mid-tarsal bones, so the midfoot and hindfoot are stiff. All of this allows the muscle gastrocnemius to act more efficiently during gait. When the tibial posterior tendon isn't in health anymore and he doesn't do his work, the other joint capsules and ligaments become weak. There is an eversion of the subtalar joint, abduction of the foot (talonavicular joint) and valgus of the heel. Also a flattened arch develops what can cause an adult acquired flatfoot. And the muscle gastrocnemius is unable to act without the posterior tibial tendon what results in affected balance and gait.

In this figure, they use 'tibialis posterior intramuscular EMG' to quantify the tibial posterior activation during walking. They used participants (female) with acute stage II PTTD. Differences in muscle activation: the participants with PTTD shows a significantly greater tibialis posterior EMG amplitude during the second half of stance phase. They walk with a pronated foot and exhibit an increased tibialis posterior activity compared to the participants without PTTD. [4]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Besides the clinical diagnosis, radiographic evaluation is required to asses deformity and the possible presence of degenerative arthritis or other causes of pes planus. MRI has the highest sensitivity, specificity and accuracy, but ultrasound is less expensive and almost as sensitive and specific as MRI. [1][5]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Before a clinical examination is performed, the patient should be submitted to a series of questions. Based on the answers the physiotherapist can rule out other disorders. It is essential to diagnose posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) in an early phase to prevent permanent deformities of the foot/ankle, and because of that a physical examination can be useful [1]. At first, look at the symptoms that can be caused by PTTD. There are many signs the physiotherapist can recognize according to the stage in which PTTD is presented. Additionally some tests can be performed.

It is important to examine the whole lower body and not just the foot, as valgus in the knees can accentuate the appearance of pes planus. The feet themselves should be examined from above, as well as from behind. A healthy person has a 5° valgus in his hindfoot, in patients with PTTD the valgus is increased and the abduction in the forefoot is also more pronounced. [6] The physiotherapist can palpate the posterior tibial tendon from above the medial malleolus to its insertion, to control the integrity and assess possible pain and swelling that are common for the first stages of PTTD. In the later stages the deformity can progress and pes planus may be visible. The physiotherapist can determine the severity of the pes planus by checking how many fingers can be passed underneath the midfoot. [1]

The diagnosis of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction can be made clinically based on history and objective testing.

The examination (objective testing) consists of several tests, namely:[7]

- the too many toes sign (Johnson): the foot should be inspected from behind and above. The too many toes sign is a manner of inspection from behind. At this manner they can establish if there is an abduction of the forefoot and a valgus angulation of the hindfoot. It is based on how many toes you can see from behind. By an affected foot it will be more than one and a half to two toes;

- the double-limb heel rise: one foot rise, while the other foot is lifted off the floor. The normal foot will stay into inversion while the affected hindfoot will stay in valgus;

- heel rise: to go with both feet from a flatfoot stance to standing on the toes. Patients in stage I dysfunction can do this, but it's painfull. Patients with stage II, III or IV dysfunction are unable to do an heel rise. When a patients stands on tiptoes the heel of the affected foot will not bend inwards;

- a single heel rise: patients can't do a single heel rise with the affected foot;

- the first metatarsal rise sign (Hintermann and Gachter): the patients stands on his both feet. The shin of the affected foot is taken with a hand and rotated externally. When the patient has PTTD, the head of metatarsal I is lifted, while normal metatarsal I stays on the ground;

- plantar flexion and inversion of the foot against resistance: to test the power of the tibialis posterior.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Foot Function Index (FFI)[8]

- 5-Minute Walk Test [8]

- Instruments to record kinematics from tibia, calcaneus and first metatarsal: e.g. Milwaukee Foot Model [8][9]

Interventions

[edit | edit source]

To decide whether patients need operative or non-operative treatment, different variables have to be taken into account by the attending physician. [10] According to Alvarez et al. (level C of evidence) non-evasive therapy, such as orthosis and physical therapy [11] are preferable for they do not damage healthy surrounding tissue, but only when non-operative treatment fails, surgical treatment is required. [10] [2]Clear evidence exists that suggests that the quality of life for patients with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is significantly affected. Furthermore, evidence suggests that early conservative intervention can significantly improve quality of life regarding disability, function, and pain... [12]

Surgical/invasive treatment

Surgical treatment can be used according to the stage in which PTTD is present.

Stage I:

- Decompression of tendon [1][13]

- Open synovectomy [1]

- Some suggest an augmentation of the abnormal tendon with flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon.[1]

Stage II: Not yet a preference to which technique should be used. Several interventions possible:

- FDL Transfer and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy [1][13]

- Lateral column lengthening (e.g. calcaneo-cuboid distraction arthrodesis) [1][14]

- Medial column fusion (navicular-cuneiform or/or metatarsal- cuneiform joint) [1]

- Isolated hindfoot fusions [1]

- Arthroereisis [1][13][14]

Stage III:

- Triple arthrodesis (subtalar, calcaneocuboid and talonavicular fusion) [1]

- Isolated hindfoot fusions (eg. subtalar fusion) or medial column fusion [1]

Stage IV:

- Pan-talar arthrodesis [1]

Non-operative treatment

The key to a successful outcome is early detection of the dysfunction. A randomised controlled trial by Kornelia Kulig et al. shows us that

- orthoses use,

- static stretching of gastrocnemius and soleus muscle,

- concentric/eccentric training of the posterior tibialis

have demonstrated success.

Participants were divided into three groups and in each group, pre- and post-intervention data (Foot Functional Index, distance traveled in the 5-Minute Walk Test and pain immediately after the 5-Minute Walk Test) were collected. The result was that concentric and eccentric progressive exercises improved perceptions of function and reduced pain (together with orthoses use and stretching). As per Kulig et al, orthoses use and eccentric training demonstrate the most improvement over a 12 week period. These results are significant (p<0,05), which means that they found a significant difference between the pre-intervention data and post-intervention data. There can be some doubt whether this is a clinically relevant study or not, because the number of participants is small. [8]

Treatment options per stages of PTTD are determined on the basis of whether there is an acute inflammation and whether the foot deformity is fixed or flexible: [3]

- Stage I: Acute: 4-8 weeks immobilisation, RICE; Chronic: flat footwear and corrective orthose or ankle foot orthosis, lace-up

- Stage II: Acute 4-8 weeks immobilisation, RICE; Chronic: lace-up, corrective orthosis and flat footwear

- Stage III: Lace-up, customised footwear or semirigid shoes and accommodative orthosis

- Stage IV: Lace-up, customised footwear or semirigid shoes and accommodative orthosis

The results of a retrospective investigation by Matthew D. Nielsen et al. support the use of a multifaceted conservative approach to the treatment of the AAFD with PTTD. This nonsurgical approach includes:

* initial immobilization

* anti-inflammatory medications

* physical therapy

* bracing

* in particular the construction of a LAFO

This aggressive nonoperative treatment regimen has been successful at alleviating symptoms in 87.5% of patients without the need for surgical intervention.[2]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

add text here

Classification

[edit | edit source]

As per Johnson and Strom [15]:

- Stage I: Posterior tibial tendon intact and inflammed, no deformity, mild swelling

- Stage II: Posterior tibial tendon dysfunctional, acquired pes planus but passively correctable, commonly unable to perform a heel raise

- Stage III: Degenerative changes in the subtalar joint and the deformity is fixed

- Stage IV ( Myerson): Valgus tilt of talus leading to lateral tibiotalar degeneration

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Elderly: especially middle aged women [1][16]

- Young athletes [1]

- Hypertension [1][16]

- Obesity [1][16]

- Diabetes mellitus [1][16]

- Seronegative arthropathies [1]

- Accessory navicular bone [1]

- Ligamentous laxity [16]

- Pes planus (flatfeet) [16]

- Steroid therapy [1][16]

- Accesory navicular: may interfere with posterior tibial tendon function [1]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Degenerative arthritis of the ankle, talonavicular or tarsometatarsal joint [1][5]

- Neuropathies of the foot caused by diabetes mellitus or peripheral neuropathies (or leprosy) [1]

- Spring ligament dysfunction [1]

- Rupture of anterior tibial tendon [1]

- Tarsal coalition [1]

- Congenital vertical talus [1]

- Kholers disease [1]

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome [1]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources[edit | edit source]

Myerson MS. Adult acquired flat foot deformity. J Bone Joint Surg.1996;45A:780-92

Hintermann B, Gachter A. The first metatarsal rise sign: a simple, sensitive sign of tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int 1996; 17:236-41.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

add text here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1vCeRl5tNk8Z6wu5F9OtxtyRcRX2OXJP58bBe_47LQlU00WkVm|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 M.R. Edwards, C. Jack, S.K. Singh. Tibialis posterior dysfunction. Current Orthopaedics, 2008; 22: 185 – 192. Level of evidence A

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Matthew D. Nielsen, Erin E. Dodson, Daniel L. Shadrick, Alan R. Catanzariti, RobertW. Mendicino, D. Scot Malay. Nonoperative Care for the Treatment of Adult-acquired Flatfoot Deformity. The Journal of Foot &amp; Ankle Surgery. 50 (2011) 311–314. (level of evidence B)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Angel JC, Singh D, Haddad F, Livingstone J, Berry G. Tibialis posterior dysfunction: a common and treatable cause of adult acquired flatfoot. BMJ.2004;329:1328-1333.(Level of evidence 2C) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Kohls" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Kohls" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Kohls" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Semple R., S Murley G., Woodburn J.and E Turner D., 'Tibialis posterior in health and disease: a review of structure and function with specific reference to electromyographic studies', Biomed Central – Journal of foot and ankle research, 2009, augustus (Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 William M. Geideman, Jeffrey E. Johnson. Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2000;30 (2) :68-77 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Geideman et al." defined multiple times with different content - ↑ David B. Thordarson. Foot and ankle. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp; Wilkins, 2004: p. 174-181

- ↑ Trnka, H.-J., 'Dysfunction of the tendon of tibialis posterior', The journal of bone and joint surgery (Br), VOL. 86-B (2004), september, nr. 7, p. 939-946 (Level of evidence 2C)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Kornelia Kulig, Stephen F Reisch I. Nonsurgical Management of Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction With Orthoses and Resistive Exercise: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Physical Therapy, 2009 Jan; 89 (1): 26-37

- ↑ Richard M. Marks, Jason T. Long. Surgical reconstruction of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: Prospective comparison of flexor digitorum longus substitution combined with lateral column lengthening or medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy. Gait & Posture, 2009 Jan;29(1):17-22

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 O'Connor K, Baumhauer J, Houck JR. Patient factors in the selection of operative versus nonoperative treatment for posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Ankle International, 2010 Mar; 31(3): 197-202. Level of evidence C

- ↑ Alvarez RG, Marini A, Schmitt C, Saltzman CL. Stage I and II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction treated by structured nonoperative management protocol: an orthosis and exercise program.. Foot Ankle Int 2006 Jan;27(1):2e8. Level of evidence C

- ↑ Durrant B, Chockalingam N, Hashmi F. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: a review. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2011 Mar-Apr;101(2):176-86. (level of evidence A)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Stephen Parsons, Soulat Naim MCh. Correction and Prevention of Deformity in Type II Tibialis Posterior Dysfunction. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 2010 Apr;468(4):1025-32. Level of evidence C

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 George A. Arangio , Eric P. Salathe. A biomechanical analysis of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy and flexor digitorum longus transfer in adult acquired flat foot. Clinical Biomechanics, 2009 May;24(4):385-90. Level of evidence C

- ↑ Johnson KA, Strom DE. Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Clin Orthop Rel Res.1989;239:196-206

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Kong, A. Van der Vliet. Imaging of tibialis posterior dysfunction. The British Journal of Radiology, 2008 Oct; 81 (970): 826–836