Sacral Insufficiency Fractures

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Sacral insufficiency fractures (SIFs) are a cause of low back pain.[1]

They are a subtype of stress fractures, resulting from normal stress applied to a bone with reduced

elasticity.[2] [3]

An underlying condition, like osteoporosis or another metabolic bone disease, is often a cause of

SIFs. This is why SIFs are more common with elderly women.[2] [3][4] Bone insufficiency fractures

in general are described first by Laurie in 1982.[3][4]

During the gait, alternating flexion and extension of the lower limbs would impart alternating

twisting forces on the pelvis around its lowest transverse axis. This effect can be shown in a

pretzel-model. When we hold a pretzel in two hands and twist it around its long axis in alternating

directions, the pretzel will snap eventually. This is what happens clinically with the sacrum during

insufficiency fractures.

As previously mentioned, this happens most frequently with elderly women, whose sacroiliac joint

is relatively ankylosed and whose sacrum has been weakend by osteoporosis. Under these

conditions, the torsional stress which is normally buffered by the sacroiliac joint, will be transferred

to the sacrum. Because of the conditions of the weakend sacrum, it fails to buffer the torsional

stress and fractures occur. In most cases, these fractures run vertically through the ala of the

sacrum parallel to the sacroiliac joint.(33)

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

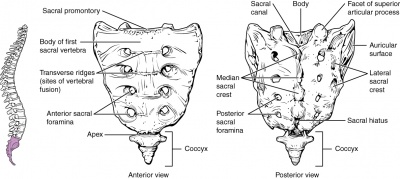

The sacrum is a triangular bone formed by 5 vertebral segments. It is broader on the superior side

than on the inferior, and broader on the anterior side than on the posterior side, allowing the

sacrum to resist shearing from vertical compression (36) as well as transfer loads from the spinal

column to the pelvis.(37)

The sacrum articulates superiorly with the fifth lumbar vertebra and inferiorly with the coccyx. The

lateral surface of the upper part of the lateral masses (auricular surface) articulates with the

ilium.[5]

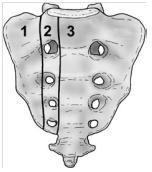

Denis et al classified traumatic sacral fractures by dividing the sacrum into 3 zones (Fig.1).This

classification system is based on the direction, the localisation and the level of the fracture.(36)

These traumatic fractures are not directly related to SIFs, but the classification system of Denis is

very useful for the description of these SIFs.[5]

Zone 1: involves the sacral ala (lateral to the sacral foramina). This is the most common area of SIFs.

Zone 2: involves the sacral (neural) foramina (but the fracture does not enter the central sacral

canal). The fractures in this site are associated with unilateral lumbosacral radiculopathies.

Zone 3: involves the sacral bodies and the transverse central canal.[2] [5]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The most important cause of SIF is osteoporosis.[2] [3] [6] [4]

Other risk factors are:

● Pelvic radiation

● Steroid-induced osteopenia [4]

● Rheumatoid arthritis [6]

● Multiple myeloma

● Paget disease [4]

● Renal osteodystrophy (13)

● Hyperparathyroidism [2] [7] [3] [4]

● Corticosteroid medication [2] [3]

● Metastatic disease [2] [3]

● Marrow replacement processes [2] [3]

● Fibrous dysplasia [7]

● Osteogenesis imperfecta [7]

● Osteopetrosis [7]

● Osteomalacia [7]

● Development of osteolysis (12)

● Radiotherapy (13)

● Diabetes mellitus (13)

● Primary biliary cirrhosis (13)

Patients with SIFs are most often women, over the age of 55, where the illness frequently occurs on both sides of the body.(17) The bone strength of these patients is inadequate to withstand normal repetitive stress (19). The average age of these patients suffering from multiple illnesses (of symptoms) (14) is between 70 and 75 years old.

The precise incidence of SIFs is unknown but some studies reported a prevalence of 1% - 5% in

at-risk patient populations. Two-third of the patients were a-traumatic. [2]

SIF can also occur to younger people, for example pregnant women. This type of SIF can be

related to pregnancy-associated osteoporosis. [7]

5. Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with SIFs may have:

● Tenderness on palpation (lower back and sacral region) [2] [8] [3] [6]

● Pain (at the buttock, low back, hip, pelvic or groin) [9] (12)

● Problems with walking (slowly and painful)

● Nerve damages (unusual) [2] [3]

● Mobility difficulties (12)

● Leg weaknesses (18)

● Parasymphyseal tenderness (suggesting associated pubic ramus fracture) (11)

● Elevated alkaline phosphatase (11)

● Plain radiograph showing pubic ramus fractures or parasymphyseal sclerosis (11)

Patients with this complications generally have a poor prognosis.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Sacral insufficiency fractures are difficult to diagnose because the signs and symptoms are

vague and non-specific. SIF’s can be mistaken for :

● Metastatic disease [3]

● Radiculopathy [2]

A condition due to a compressed nerve in the spine that can cause pain, numbness,

tingling, or weakness along the course of the nerve. (21)

● Disc disease

● Spinal stenosis

A narrowing of the open spaces within the spine, which can put pressure on the spinal

cord. (24)

● Cauda equina syndrome

Refers to a dysfunction of the cauda equina, the collection of ventral and dorsal lumbar,

sacral and coccygeal nerve roots that surround the filum terminale. (23)

● Osteodegenerative diseases (history of trauma) (13)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

SIF can be diagnosed using radiology. Bone scintigraphy/scan(16) is the most accurate test to detect SIFs. Another radiographic procedure that can help to diagnose SIF’s is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is considered as a more sensitive diagnostic tool. (19, 20). There is also single-photon emission-computed tomography with low-dose computed tomography (CT) which

reveals the correct diagnosis. (22)

Difficulties in the diagnostic process and the validity of imaging techniques are highlighted. (18) First of all, the exact locations of sacral insufficiency fractures were catalogued and compared to sacral anatomy. Then, different routine activities were simulated by pelvic models from CT scans of the pelvis and limited element analysis. Analyses were done to correlate areas of stress with activities within the sacrum and pelvis, and these analyses are then compared with patterns of sacral insufficiency fractures. (15)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

An outcome measure appropriate for this injury is the VAS-score, which measures the pain intensity of the patient.(25)

Examination[edit | edit source]

Usually the examination involves: interrogation of the patient, physical examination, sometimes

neurological examination, laboratory investigations and finally imaging. (26,27,28)

The examination begins with the history of the patient. The patient can report sudden pain in the

lower back and pelvic region. This is accompanied with reduction of mobility and independence.

Symptoms are worsened by weight bearing activities and are generally improve with rest. These

patients usually feel the most comfortable in the supine position. (28)

The physical examination shows: [5]

● Sacral tenderness (on lateral compression)

● SI-joint tests are often positive (this test is not specific for SFI)

● Gait is usually slow and antalgic

● Trendelenburg test is usually normal

● Sciatic nerve tension test (Lasegue and Straight Leg Raise (SLR)) is usually normal

Other clinical test that may aid the diagnosis of sacral insufficiency fractures : Hip flexionabduction-external

rotation test (FABER test), Gaeslen’s test and Squish test. These tests are not

specific for SIF but may indicate a pathology on the sacroiliac joint.(28)

The neurological examination is often normal.(28)

Laboratory investigations can also be done. Bone alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is a marker of bone

formation. The serum levels of ALP are often lightly raised in patients with SIF. (28)

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Generally sacral insufficiency fractures are treated conservatively with bed rest and analgesia,

follow by physical therapy(25 LOE 4,26 LOE 2B,27 LOE 1C ,28 LOE 2A,29 LOE 5). The disadvantages of conservative management can include severe pain, significant morbidity and mortality and prolonged

immobility(25 LOE 4). Early ambulation may reduce these complications(29 LOE 5).

Percutaneous sacroplasty is a variation of percutaneous vertebroplasty. It is an alternative that

may provide symptomatic relief and accelerate the recovery[[|]](30 LOE 2B). Sacroplasty involves the

precutaneous insertion of 1 or more bone needles into the fracture zone of the sacral ala. PMMA

(polymethylmethacrylate) cement is then injected in this zone with the aim to treat the lesion and

to stabilize the sacrum (25 LOE 4). Carina L. Et al. discribed that CT guidance can improve this

procedure (30 LOE 2B)

.

Sacroplasty provides symptom relief including pain relief and functional restoration. The quality of

life of the patients is improved and the complications of immobility are avoided. However the longterm

results of sacroplasty are not known yet (31 LOE 1C). Further research into the effectiveness of

sacroplasty is required (25 LOE 4,30 LOE 2B,31 LOE 1C).

Rinoo V. Et al. discribed a different procedure called sacral kyphoplasty. This is a modification of

sacroplasty. It involves the use of an extensible balloon to create a bone void before injecting the

cement. Sacral kyphoplasty appears to be safe, usefull and efficient. It should optimize the

procedural safety(32 LOE 2B).

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Early rehabilitation and moderate weight-bearing exercises, within the boundaries of pain tolerance,

have been suggested. Earlier rehabilitation will stimulate the bone formation by the osteoblasts and

improve muscle tension.

In the earlier stages of fracture healing, mobilization can be assisted by the use of external devices (e.g.

walking frames) or hydrotherapy which is typically better tolerated by many patients. [5](C)

Intervention of manual therapy was utilized to treat the L5 dysfunction and the right sacroiliac

joint. The manual therapy techniques were followed by passive stretching of the hip into flexion,

medial rotation, and adduction. The reassessment of the sacral position with the patient positioned

prone and prone on elbows revealed symmetric sacral bony landmarks (SB and ILA), byfollowing

these interventions. In addition, (posterior-anterior) PA pressures over the right sacral base, did

not help for hypermobility. From the article of Boissonnault WG et al. we can conclude that thanks

to manual therapy the return to work is eight weeks. 34 (1C)

From the article of V. Longhino et al. we learned that it is useful to start with early mobilization.

This early mobilization will prevent the acceleration of bone mineral density, the increased

incidence of deep vein thrombosis, possible pulmonary embolus as well as loss of muscle strength

due the immobilization period of 3-6 months. An early rehabilitation including weight-bearing and

muscle tension exercises stimulates osteoblastic activity, which results in bone formation. 35 (3A)

The use of Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) and low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPU) can

also be used for healing fractures. These techniques stimulate several growth factors (including

BMPs and TGF-β) as well as some proteins such as calmodulin. These are in fact the substances

required for the physiological bone healing process. 35 (3A)

Extracorporal shock wave therapy can also be used. Like the PEMF and the LIPU techniques it

stimulates growth factors where the body shock is applied. The aim of this shock wave therapy is

to increase bone repair, by increasing the proliferation of osteoblasts, which leads to bone

formation. 35 (3A)

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

More awareness for SIFs as a cause of low back pain is needed. This would be beneficial for the prevention of misdiagnosis or misinterpretation of metastasis.(38),(39) Stress-related bone changes shown on imaging examinations may not always be symptomatic and may disappear without ever becoming symptomatic. (38)

Once the patient has been diagnosed with an SIF it is necessary that he resumes weight-bearing activities under supervision of a healthcare professionals.(40) Physiotherapy also considers gradual mobilisations with walking aids as pain allows.(42) Analgesics may also be prescribed to reduce the pain. Sacroplasty can also be considered, where surgeons inject the bone with cement to ease the pain and increase the supportive role of the sacral bone. Technical success of sacroplasty is assessed in terms of cement filling and leakage.(40),(41)

[edit | edit source]

Matthew J. Baldin, Sacral insufficiency fractures: a case of mistaken identity, Int Med Case Rep J. 2014; 7: 93–98 Bernhard J. Tins, Stress fracture of the pelvis and lower limbs including atypical femoral fractures—a review, Insights Imaging. 2015 Feb; 6(1): 97–110

References[edit | edit source]

2. ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Lyders E.M., Whitlow C.T., Baker M.D., Morris P.P., Imaging and treatment of sacral insufficiency fractures (review), Am. J. Neuroradiology 31:201-10, February 2010.(Levels of evidence: 2C)

3. ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Wild A., Jaeger M., Haak H., Mehdian S.H., Sacral insufficiency fracture, an unsuspected cause of low-back pain in elderly women. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg (2002) 122:58-60.(Levels of evidence: 3B)

4. ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Yong-Lee J., Bong-Jin H., Kim J.T., Chung D.S., Sacral insufficiency fracture, most overlooked cause of lumbosacral pain. J. Kor. Neurosurg. Soc. September 2008, 44 (3): 166-169.(Levels of evidence: 3B)

5. ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Tsiridis E., Upadhyay N., Giannoudis P.V., Sacral insufficiency fractures: current concepts of management. Osteoporos. Int. (2006) 17: 1716-1725.(Levels of evidence: 5)

6. ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Dasgupta B., Shah N., Brown H., Gordon T.E., Tanqueray A.B., Mellor J.A., Sacral insufficiency fractures: an unsuspected cause of low back pain. British Journal of Rheumatology 1998; 37: 789-793.(Levels of evidence: 3A)

7. ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 KARATAS M., BASARAN C., OZGUL E., TARHAN E., AGILDERE A.M., Postpartum sacral stress fracture, An unusual case of low-back and buttock pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Vol 87, No. 5. 2008.(Levels of evidence: 3B)

8. ↑ KOS C.B., TACONIS W.K., VAN DER EIJKEN J.W., Insufficiëntiefracturen van het sacrum, Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd 1999, 13 februari; 143(7).(Levels of evidence: 3A)

9. ↑ THEIN R., BURSTEIN G., SHABSHIN N., Labor-related sacral stress fracture presenting as lower limb radicular pain. Orthopedics June 2009; 32(6):447.(Levels of evidence: 3B)

10. ↑ GOTIS-GRAHAM I., McGUIGAN L., DIAMOND T., PORTEK I., QUINN R., STURGESS A., TULLOCH R., Sacral insufficiency fractures in the elderly. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994; 76-B: 882-6.(Levels of evidence: 3A)

11. B. DASGUPTA, SACRAL INSUFFICIENCY FRACTURES: AN UNSUSPECTED CAUSE OF LOW BACK PAIN, British Journal of Rheumatology 1998;37:789–793 (level of evidence : 3A) 12. Spalteholz M etal. ; 4-point internal fixator stabilization of a sacral insufficiency fracture ; Unfallchirurg. 2015 Feb;118(2):181-7. doi: 10.1007/s00113-014-2590-7. (3B) 13. Ayhan AŞKIN et al. ; ATYPICAL SACRAL AND ILIAC BONE INSUFFICIENCY FRACTURES IN A PATIENT RECEIVING LONG-TERM BISPHOSPHONATE THERAPY ; 2015, Cilt 18, Sayı 2, Sayfa(lar) 171-175 (3B) 14. Christopher Wilhelm Ludtke et al. ; Treatment of a Bilateral Sacral Insufficiency Fracture with CT-Guided Balloon Sacroplasty ; Iran J Radiol. 2014 Aug; 11(3): e6965. Published online 2014 Aug 1. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.6965 (3A) 15. Nathan J. Linstrom et al. ; Anatomical and Biomechanical Analyses of the Unique and Consistent Locations of Sacral Insufficiency Fractures ; Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Author manuscript; available in PMC 2009 Jul 13. (3A) 16. I. GOTIS-GRAHAM et al. ; SACRAL INSUFFICIENCY FRACTURES IN THE ELDERLY ; HE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY (2B) 17. S P Blake etal. ; Sacral insufficiency fracture; Department of Radiology, South Infirmary-Victoria Hospital, Old Blackrock Road, Cork, Ireland and 2Department of Radiology, Charing Cross Hospital, Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8RF, UK (2C) 18. R Watura et al. ; Sacral insufficiency fractures ; Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2007;15(3):339-46 (2B)

19. Geiselhart HP, Abele T. Multiple stress fractures of the anterior and posterior pelvic ring with progressive instability. Description of a pronounced case with review of the literature [in German]. Unfallchirurg 1999;102:656–61. (3B) 20. Grangier C, Garcia J, Howarth NR, May M, Rossier P.; Role of MRI in the diagnosis of insufficiency fractures of the sacrum and acetabular roof. Skeletal Radiol 1997;26:517–24 (3A) 21. http://www.medicinenet.com/radiculopathy/article.htm#what_is_radiculopathy geraadpleegd op 17/10/2015 22. Oksana Lapina etal. ; Sacral insufficiency fracture after pelvic radiotherapy: A diagnostic challenge for a radiologist ; Article history: Received 15 May 2014 Accepted 13 September 2014 Available online 1 October 2014 ; m e d i c i n a 5 0 ( 2 0 1 4 ) 2 4 9 – 2 5 4 (3B) 23. Bennett SJ etal.; Neoplastic cauda equina syndrome: a neuroimaging-based review; Pract Neurol. 2015 Oct 6. pii: practneurol-2015-001236. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001236. (2C) 24. Velandy Manohar; Epidural steroid injections are not effective for patients with lumbar spinal stenosis; Evid Based Med. 12 april 2015 (5)

25. Bayley E. Et al.; Clinical outcomes of sacroplasty in sacral insufficiency fractures: a review of the literature; Eur Spine J;2009; 18:1266-1271 (Level of evidence: 4 ; Grade of Recommandation: C )

26. Dasgupta B. Et al.; Sacral insufficiency fractures: An unsuspected cause of low back pain; British Journal of Rheumatology; 1998; 37:789-793 (Level of evidence: 2B ; Grade of Recommandation: C )

27. Wild A. et al.; Sacral insufficiency fracture, an unsuspected cause of low-back pain in eldery woman; Arch Orthop Trauma Surg; 2002; 122:58-60 (Level of evidence: 1C ; Grade of Recommandation: A )

28. E. Tsiridis et al. ; Sacral insufficiency fractures : current concepts of management ; International Osteoporosis Foundation and National Osteoporosis Foundation ; 2006 ; 17 :1716-1725 (Level of evidence: 2A ; Grade of Recommandation: B )

29. Silver D.A.T. et al.; CT-guided sacroplasty for the treatment of sacral insufficiency fractures; Clinical Radiology;2007; 62:1101-1103 (Level of evidence: 5 ; Grade of Recommandation: F )

30. Carina L. ;Percutaneous Sacroplasty for the treatment of sacral insufficiency fractures ;American Journal of Roentgenology ;2005 ;184-6 (Level of evidence: 2B ; Grade of Recommandation: B)

31. William Pommersheim et al. ;Sacroplasty : A Treatment for Sacral Insufficiency Fractures ;American Journal of Neuroradiology ; 2003 ;24 :1003-1007 (Level of evidence: 1C ; Grade of Recommandation: B)

32. Rinoo V.; Sacral kyphoplasty for the treatment of painful sacral insufficiency fractures and metastases; The Spine Journal; 2012; 12:113-120 (Level of evidence: 2B ; Grade of Recommandation: B)

33. Cohen, Steven P. MD; Sacroiliac Joint Pain : A Comprehensive Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis and Treatment; Official Journal of the International Anesthesia Research Society; 2005; Level of Evidence : 2A

34. Boissonnault WG, Thein-Nissenbaum JM. Differential diagnosis of a sacral stress fracture. J Orth Sport Phys Ther. 2002;32(12):613-621. (Level of evidence: 1C ; Grade of Recommandation: A)

35. Valentina Longhino, Cristina Bonora, et al ; The management of sacral stress fractures: current concepts. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism 2011; 8(3): 19-231 (Level of evidence:3A ; Grade of Recommandation: C)

36. M. Bydon; Sacral fractures; Neurosurg Focus; 37 (1); July 2014 (Level of evidence : 3A)

37. A. Vleeming; The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications; Journal of Anatomy; 221; 537-567; 2012 (Level of evidence : 4)

38. BERNHARD J., Stress fracture of the pelvis and lower limbs including atypical femoral fractures- a review. 2014, Insights imaging. (Level of evidence : 3A)

39. M. J. Baldwin; Sacral insufficiency fractures: a case of mistaken identity; international medical case reports journal; 7 93-98; May 2014 (Level of evidence : 3B)

40. Valentina L.; The management of sacral stress fractures: current concepts; Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism; 2011; 8(3): 19-23. (Level of evidence : 2A)

41. S. E. Kang; Percutaneous sacroplasty with the use of C-arm flat-panel detector CT: technical feasibility and clinical outcome; Skeletal Radiology; 2011; 40: 453-460

42. E. Tsiridis; Sacral insufficiency fractures: current concepts of management; Osteoporos Int (2006) 17:1716–1725 (Level of Evidence : 2B)