Tendinopathy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

<u>Tendinopathy is usually seen in:</u> | <u>Tendinopathy is usually seen in:</u> | ||

*[[ | *[[Lateral Epicondylitis|Lateral Epicondylitis]] | ||

*[[ | *[[Medial Epicondylitis|Medial Epicondylitis ]] | ||

*[[ | *[[Patellar Tendinitis|Patellar tendon]] | ||

*[[ | *[[Achilles Tendonitis|Achilles Tendon]] | ||

*[[ | *[[Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy|Rotator cuff ]]<br><br> | ||

'''History'''<br><br>The classic presentation is one of increasing pain at the site of the affected tendon, often with recognition that there has been an increase inactivity. Usually the pain is load-related. | |||

In very early tendinopathy, pain may be present at the beginning of an activity and then disappear during activity itself, only to reappear when cooling down if the activity is prolonged, or to be more severe on subsequent attempts to be active. The patient is usually capable to localize the pain rather clearly and the pain is described as ‘‘severe’’ or ‘‘sharp’’ during the early stages and sometimes as a ‘‘dull ache’’ once it has been present for some weeks. <br><br> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

Revision as of 19:14, 26 May 2011

Original Editors - Matthias Verlinden

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Engine: Pubmed, Articledatabase, Web of Knowledge

Keywords: Tendinopathy, review, (tendinitis, tendinosis)

Inclusion criteria: <10years – April 2011, English, accessible

Exclusion criteria: Non-English

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Tendinopathy is a failed healing response of the tendon, with haphazard proliferation of tenocytes, intracellular abnormalities in tenocytes, disruption of collagen fibers, and a subsequent increase in noncollagenous matrix.[1][2][3] The term tendinopathy is a generic descriptor of the clinical conditions ( both pain and pathological characteristics) associated with overuse in and around tendons.[4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

Healthy tendons are brilliant white in color and have a fibroelastic structure. Within the extracellular network , tenoblasts and tenocytes constitute about 90% to 95% of the cellular elements of tendons.[5] The remaining 5% to 10% of the cellular elements of tendons consists of chondrocytes at the bone attachment and insertion sites, synovial cells of the tendon sheath, and vascular cells, including capillary endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells of arterioles.

The oxygen consumption of tendons and ligaments is 7.5 times lower than that of skeletal muscles. The low metabolic rate and well-developed anaerobic energy-generation capacity are essential to carry loads and maintain tension for long periods, reducing the risk of ischemia and subsequent necrosis. However, a low metabolic rate results in slow healing after injury.[6]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Tendinopathic tendons have an increased rate of matrix remodeling, leading to a mechanically less stable tendon that is probably more susceptible to damage.[7] Histological studies of surgical specimens from patients with established tendinopathy consistently show either absent or minimal inflammation.[8][9][10] They generally also show hypercellularity, a loss of the tightly bundled collagen fiber appearance, an increase in proteoglycan content, and commonly neovascularization.[11][12] Inflammation seems to play a role only in the initiation, but not in the propagation and progression, of the disease process.[13] Failed healing and tendinopathic features have been associated with chronic overload, but the same histopathological characteristics also have been described when a tendon is unloaded: stress shielding seems to exert a deleterious effect.[8] Unloading a tendon induces cell and matrix changes similar to those seen in an overloaded state and decreases the mechanical integrity of the tendon.[14][15][16]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Tendinopathy is usually seen in:

History

The classic presentation is one of increasing pain at the site of the affected tendon, often with recognition that there has been an increase inactivity. Usually the pain is load-related.

In very early tendinopathy, pain may be present at the beginning of an activity and then disappear during activity itself, only to reappear when cooling down if the activity is prolonged, or to be more severe on subsequent attempts to be active. The patient is usually capable to localize the pain rather clearly and the pain is described as ‘‘severe’’ or ‘‘sharp’’ during the early stages and sometimes as a ‘‘dull ache’’ once it has been present for some weeks.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

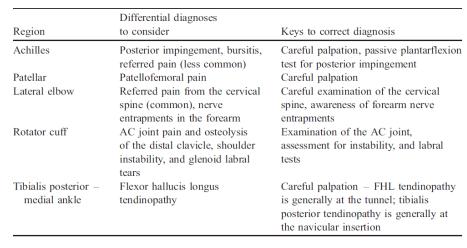

Specific differential diagnoses to consider when patients present with ‘tendinopathy’ at various anatomical regions.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION[17]

Examination includes inspection for muscle atrophy, asymmetry, swelling and erythema. Atrophy often is present with chronic conditions and is an important clue to the duration of the tendinopathy. Swelling, erythema, and asymmetry are commonly noted when examining pathologic tendons. Range-of-motion testing often is limited on the symptomatic side.

Physical examination must include tests that load the tendon to reproduce pain and other loading tests that load alternative structures.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (also see Outcome Measures Database)

Examination[edit | edit source]

add text here related to physical examination and assessment

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Use of injectable substances:

Corticosteroids improve short-term outcomes but are worse than no intervention or physiotherapy for intermediate- and long-term outcomes for some types of tendinopathy. Evidence is insufficient to evaluate effectiveness of other types of injection.[18]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Eccentric exercises:

Eccentric exercises have been proposed to promote collagen fiber cross-link formation within the tendon, thereby facilitating tendon remodeling.[19] The basic principles in an eccentric loading regimen are unknown, although it has been speculated that forces generated during eccentric loading are of a greater magnitude than those in concentric exercises.[20] It is possible that eccentric exercises do not just exert a beneficial mechanical effect, but also act on pain mediators, decreasing their presence in tendinopathic tendons. following eccentric training intervention.[21] Excellent clinical results have been reported both in athletic and sedentary patients.[22][23] although these results were not reproduced by other study groups.[24] In general, the overall trend suggests a positive effect of eccentric exercises, with no reported adverse effects.[19] In one study, the combination of eccentric training and shock wave therapy produced success rates that were higher than those with eccentric loading alone or shock wave therapy alone.[25]

There is little consensus regarding which variables may influence the outcome of eccentric training, including whether training should be painful, home- vs clinic-based training, the speed of the exercise, the duration of eccentric training and the method of progression. Three basic principles in an eccentric loading regime have been proposed [19]:

- Length of tendon: if the tendon is pre-stretched, its resting length is increased, and there will be less strain on that tendon during movement.

- Load: by progressively increasing the load exerted on the tendon, there should be a resultant increase in inherent strength of the tendon.

- Speed: by increasing the speed of contraction, a greater force will be developed.

Yet more research is needed to confirm these modalities.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy:

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy to address the failed healing response of a tendon is becoming more widely used among the medical community.[26]

The rationale for the clinical use of extracorporeal shock wave therapy is stimulation of soft-tissue healing and inhibition of pain receptors. There is no consensus on the use of repetitive low-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy, which does not require local anesthesia, versus the use of high-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy, which requires local or regional anesthesia.[27]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add links and reviews of high quality evidence here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

In general, it would be reasonable to treat a patient with tendinopathy with physical therapy involving a program of eccentric exercises, to be performed for twelve weeks. If the condition does not respond to this intervention, shock wave therapy or a nitric oxide patch[28] might be considered, although data on their efficacy are limited. The use of operative treatment should be discussed with the patient after at least three to six months of nonoperative management. Moreover, patients should understand that symptoms may recur with either conservative or operative approaches.[1]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Maffulli et al. Novel Approaches for the Management of Tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2604-2613. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01744 (Evidence level A1)

- ↑ Maffulli N, Longo UG, Maffulli GD, Rabitti C, Khanna A, Denaro V. Marked pathological changes proximal and distal to the site of rupture in acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010 Jun 19 [Epub ahead of print]. (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Maffulli N, Longo UG, Franceschi F, Rabitti C, Denaro V. Movin and Bonar scores assess the same characteristics of tendon histology. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008; 466:1605-11. (Evidence level A2)

- ↑ Maffulli N, Khan KM, Puddu G. Overuse tendon conditions: time to change a confusing terminology. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:840-3.

- ↑ Kannus P, Jozsa L, Jarvinnen M. Basic science of tendons. In: Garrett WE Jr, Speer KP, Kirkendall DT, editors. Principles and practice of orthopaedic sports medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000. p 21-37. (Book)

- ↑ Williams JG. Achilles tendon lesions in sport. Sports Med. 1986;3:114-35.

- ↑ Arya S, Kulig K. Tendinopathy alters mechanical and material properties of the Achilles tendon. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:670-5. (Evidence level B )

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Longo UG, Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Rabitti C, Morini S, Maffulli N, Forriol F, Denaro V. Light microscopic histology of supraspinatus tendon ruptures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1390-4. (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Longo UG, Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Rabitti C, Morini S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Characteristics at haematoxylin and eosin staining of ruptures of the long head of the biceps tendon. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:603-7.

- ↑ Longo UG, Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Rabitti C, Morini S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Histopathology of the supraspinatus tendon in rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:533-8. (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Longo UG, Ronga M, Maffulli N. Acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2009;17:127-38.

- ↑ Longo UG, Ronga M, Maffulli N. Achilles tendinopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2009;17:112-26.

- ↑ Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J. Management of tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1855-67. (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: a model for the continuum of pathology and related management. Br J Sports Med. 2010 Jun 11.

- ↑ Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:409-16

- ↑ Louis C. et al. Strain patterns in the patellar tendon and the implications for patellar tendinopathy. Knee Surg, Sports Traumatol, Arthrosc (2002) 10 :2–5 (Evidence level B)

- ↑ John J. Wilson, M.D., And Thomas M. Best, M.D., Ph.D. Common Overuse Tendon Problems: A Review and Recommendations for Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(5):811-818. (A1)

- ↑ Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376: 1751-67. (Evidence level A1)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Maffulli N, Longo UG. How do eccentric exercises work in tendinopathy? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1444-5. (Evidence level A2)

- ↑ Rees JD, Lichtwark GA, Wolman RL, Wilson AM. The mechanism for efficacy of eccentric loading in Achilles tendon injury; an in vivo study in humans. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1493-7. (Evidence level C)

- ↑ Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Effects on neovascularisation behind the good results with eccentric training in chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinosis? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:465-70. (Evidence level C)

- ↑ Roos EM, Engstr¨om M, Lagerquist A, S¨oderberg B. Clinical improvement after 6 weeks of eccentric exercise in patients with mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy— a randomized trial with 1-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2004;14:286-95 (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Mafi N, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Superior short-term results with eccentric calf muscle training compared to concentric training in a randomized prospective multicenter study on patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:42-7

- ↑ Maffulli N, Longo UG, Loppini M, Denaro V. Current treatment options for tendinopathy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:2177-86. (Evidence level A1)

- ↑ Rompe JD, Furia J, Maffulli N. Eccentric loading versus eccentric loading plus shock-wave treatment for midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:463-70. (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Rompe JD, Nafe B, Furia JP, Maffulli N. Eccentric loading, shock-wave treatment, or a wait-and-see policy for tendinopathy of the main body of tendo Achillis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:374-83 (Evidence level B)

- ↑ Rompe JD, Maffulli N. Repetitive shock wave therapy for lateral elbow tendinopathy (tennis elbow): a systematic and qualitative analysis. Br Med Bull. 2007; 83:355-78. (Evidence level A1)

- ↑ George AC Murrell Using nitric oxide to treat tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:227–231. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.034447 (Evidence level A2)