Total Ankle Arthroplasty

Original Editor - Jeremy Brady

Lead Editors - Jeremy Brady, Neha Palsule, Jorge Solorzano, Tori Westcott, Dana Williams

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases Searched: PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane, JOSPT

Keywords Searched: ankle arthroplasty, ankle physical therapy, ankle replacement, total ankle arthroplasty, total ankle replacement

Search Timeline: June 11th 2011 - July 15th 2011

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Poor patient satisfaction, high rates of revision due to loosening, and high wound complications rates were all very problematic when total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) surgeries were first introduced in the 1970’s.[1] In 1990, noncemented prostheses were shown to allow for bony ingrowth and less bone removal as compared to cemented.[1] Beyond the transition to cementless, further advances in technology over the years has led to new surgical arthroplasty techniques, primarily moving from a two-component design to a 3-component model.

An observational study analyzed advantages of arthroplasty over arthrodesis stating individuals with monoarticular or polyarticular disease who undergo arthroplasty have less gait abnormalities and fewer adverse effects to other joints in the lower extremity.[2] A systematic review provided that in 852 individuals undergoing TAA's, there was a 78% implant survival 5 years post-op and 77% at 10 years post-op and overall only had a 7% revision rate. This provides evidence that the procedure yields satisfactory results and should be considered for potential candidates that are appropriate for surgical corrections.[3]

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

The ankle joint, formed by the tibia, fibula, and talus, has articular cartilage that differs from that in the hip and knee due to the fact it preserves its tensile stiffness and stresses better. However, the small contact area may indicate higher contact stresses than the hip or knee experience.[4]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Indications:

According to JOSPT, there are no exact indications for receiving a total ankle arthroplasty.[4] The “ideal” patient who would typically undergo this intervention is one who is elderly with a healthy immunity, normal vascular status, good bone density, and a proper hindfoot-ankle alignment who has not had success with conservative treatment measures. Individuals with debilitating ankle arthritis, unresponsive to nonoperative approaches, or have failures with the outcome of their ankle arthroplasty are typically treated with an arthrodesis procedure to fuse the joint.

Contraindications:

Arthroplasty is contraindicated for those with neuroarthropathic degenerative joint disease, infection, avascular necrosis of the talus, osteochondritis dessicans, malalignment of the hindfoot-ankle, severe benign joint hypermobility syndromes or soft tissue problems, or decreased sensation or motion in the lower extremities.[1] In individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory processes may occur before signs of swelling, tissue reaction, and joint destruction are seen. In the first and second year of this disease process, structural damage (ie. joint erosion) can be seen with X-ray imaging.[5] Diabetic patients may develop gouty arthritis in their ankle joint. This is caused by uric acid changing into urate crystals, which is deposited into the joint.[5]

Thus, RA and diabetic individuals may or may not be candidates for ankle arthroplasty depending on the severity of joint degeneration found with radiographic imaging.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Precautions and Contraindications:[edit | edit source]

It is essential to obtain weight-bearing status and ROM protocol from the physician prior to any evaluation procedures. Generally, the patient is non weight bearing for 6 weeks with ROM restricted for the first 2 weeks postop to allow for wound healing. The patient must be continually assessed for signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or infection.[6]

History Key Points:[edit | edit source]

- Mechanism of injury or etiology of illness

- Date of surgery and type of implant

- Use of assistive device with weight bearing status

- Use of controlled ankle motion (CAM) walker/walking boot

- Functional deficits/assistance with ADLs/adaptive equipment

- Pain/ Symptom history: Location, duration, type, intensity (VAS), aggravating and relieving factors, 24 hour symptom behavior

- Relevant Current/Past Medical history: Other lower extremity arthritis or injuries,upper extremity issues that may limit ability to ambulate with an AD and comorbid diagnoses

- Medications for current/previous diagnoses

- Diagnostic tests

- Sleep disturbance

- Barriers to learning

- Social/occupational history

- Patient’s goals

- Vocation/avocation and associated repetitive behaviors

- Living environment

Relevant Tests & Measures:[edit | edit source]

- Observation/inspection/palpation: Skin and incision assessment, edema, muscle atrophy

- Circulation: Dorsal pedal pulse

- Sensory and proprioception testing

- Range of motion and Muscle length: Average postoperative arc of motion (dorsifexion and plantarfexion) is 23°[6][7]

- Muscle strength

- Posture: Increased pronation/supination in standing, ability to maintain wait bearing status

- Assess assistive and adaptive devices for need and proper fit

- Balance: Static and dynamic standing balance, unilateral balance of the unaffected extremity (especially if patient is still non-weight bearing).[6] Patient may demonstrate dynamic postural imbalance, less reliance on ankle strategy and deficit of motor control ability[8]

- Functional mobility

- Gait Assessment[6]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

First generation:[edit | edit source]

Early ankle prosthesis attempts involved cementing a stemmed metal ball into the tibia and a polyethylene cup cemented into the talus. Throughout the 1970’s, prosthesis evolved into using a vitallium component cemented into the talus. All designs used methylmethacrylate cement, which became the defining element of first generation prosthesis.[1]

Types:[edit | edit source]

- Constrained - Increased stability due to only allowing dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. Loosening of the prosthesis was common from increased torque at the joint.[1]

- Nonconstrained - Allows full ROM, resulting in decreased stability that commonly caused impingement against the medial and/or lateral malleoli.

- Semiconstrained - A combination of contrained and nonconstrained models, allowing greater ROM and medial-lateral stability. The Imperial College, London Hospital prosthesis uses a concave polyethylene in the tibia and a stainless steel component on the talus.[1]

Unfortunately, by the early 1980’s, first generation ankle arthroplasties were not recommended by the majority of orthaepedic surgeons. Numerous studies showed loosening of the cement fixation, wound issues, and low patient satisfaction [4][1]. As a result of the poor outcomes and high complication rate, surgeons began to recommended ankle arthrodesis.

Second generation:[edit | edit source]

Second generation arthroplasties are cementless, using bony ingrowth to stabilize the implant. Compared to cement, bony ingrowth prosthesis have less bone resection, damage to soft tissue and complications of the cement such as cement displacement[4].

Surgical Factors:[edit | edit source]

- Fixation: Ingrowth implants tend to have either a beaded surface along the bony interface, hydroxyapatite layer or a combination of both. Current surgical designs tend to use the combination fixation technique.[1][4] Between types of prosthesis the number of articulating surfaces and components both need to be considered.[4][1][11].

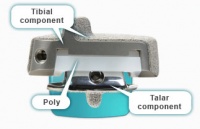

- Components:

- Articulating surfaces: Current designs vary on the articulations that need to be resurfaced. Resurfacing may occur at the superior tibiotalar joint, superior and medial articulations, or medial, lateral, and superior joints.[1] Determining which patients would benefit the most from each type of surgery is ongoing.[4]

Design components:[edit | edit source]

- 2 component implants include a tibial and talar articulating component. Implants may also incorporate syndesmosis fusion to resurface the medial and lateral recesses of ankle and converting the ankle from a 3-bone joint to a 2-bone joint. Known designs: Agility, Salto Talaris, Eclipse, INBONE

- Advantages: decreased shear and torsion on prosthesis[12], syndesmosis decreases shear force and increase the bony support for the tibial component[4]

- Disadvantages: increased bony resection, likelihood of soft tissue compromise, accelerated polyethylene wear, and possibility of syndesmosis fusion failure.[4]

|

|

| Salto Talaris | Agility |

- 3 component implants include a “mobile bearing” of polyethylene between the tibial plate and talar component. Known designs: Buechel-Pappas, Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement (STAR), Mobility, HINTEGRA

|

|

| STAR | Buechel Pappas |

Both component designs permit semiconstrained motion, specifically allowing some inversion and eversion during sagittal plane ankle movement. The four 2 component designs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The STAR was recommended for approval by the FDA in 2008.[13][12] There is insufficient evidence determining the life expectancy of current prosthesis designs.[12]

Alternate Option:[edit | edit source]

Ankle Arthrodesis

Ankle arthrodesis or fusion was the recommended surgical option after the failure of the first generation ankle arthroplasty. The procedure includes resecting the articular surfaces of the joint, realignment the talus and tibia and fusing the bones together. As a result, the ankle joint doesn’t allow any motion. The goal of ankle arthrodesis is pain relief.[14][11] Unfortunately, the lack of ankle motion can cause elevated stress on the knee and hindfoot and in addition, increases motion at the hindfoot that may become arthritic.[1] Other complications of fusion include accelerated degeneration of adjacent joint and limitations in activity.[12]

| Used with permission by Susan Barber Lindquist, Media Relations Coordinator, Mayo Clinic Health System[15] |

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

As can be expected after any type of surgery, pain and inflammation must be controlled. This is the case especially after ankle replacement because pain and inflammation can last up to 12 months after surgery.[16] Surrounding muscles can be damaged during surgery and can result in decreased range of motion and strength.[17][18][19] Damage to joint proprioceptors during excision of the capsule may cause deficits in both static and dynamic balance.[8][20] These components can lead to gait disability and decreased efficiency of locomotion.[21] Correction of gait posture and ambulation deficiencies will be a target of therapy once the patient is ambulating independently.

Physical Therapy Goals:[edit | edit source]

- Decrease pain

- Decrease inflammation

- Increase strength

- Increase range of motion

- Improve dynamic and static balance

- Improve proprioception

- Proper independent ambulation

Medical Precautions:[22][edit | edit source]

- Immobilization

- 0-2 weeks: short leg cast

- 2-6 weeks: splint, can be removed during therapy

- Mobilization

- 0-6 weeks: non-weight bearing

- >6 weeks: weight bearing as tolerated with assistive device

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Pain and inflammation:[16][22][edit | edit source]

- Pain relievers

- Anti-inflammatory drugs

- RICE

Mobility:[edit | edit source]

- Education on weight-bearing status

- Education on proper ambulatory technique using assistive device

Range of Motion:[17][18][19][edit | edit source]

- 2-6 weeks: Active and passive ankle dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion, eversion, toe flexion and extension

- >6 weeks: Aggressive stretching emphasizing dorsiflexion

Strength:[edit | edit source]

- 2-6 weeks: Light Thera-band resistive exercises into dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion and eversion

- >6 weeks: Increase Thera-band resistance. Resisted adduction with inversion and resisted abduction with eversion. Begin weight-bearing activities such as toe and heel raises

Proprioception and balance:[8][20][edit | edit source]

- Seated rocker board exercise (dorsiflexion to plantarflesion and inversion to eversion. May progress to standing as indicated

- Fallproof Program:

- Focuses on strength, balance, endurance and flexibility during functional activities such as single-limb stance on stable and unstable surface, standing on toes, standing on toes and reaching and bending forward to reach objects on ground.

- http://www.exrx.net/Store/HK/Fallproof.html

Independent ambulation:[21][edit | edit source]

- Gait training with direction toward normalization

Sample Exercises[edit | edit source]

|

|

|

| Balance c perturbation | Ball toss | Standing reach |

|

|

|

| Standing reach | Seated rocker board | DF theraband |

|

|

|

| Ankle eversion | DF stretch | Ankle PF |

Key Research[edit | edit source]

- Saltzman, C.L., McIff, T.E., Buckwalter, J.A., Brown, T.D. Total Ankle Replacement Revisited. JOSPT. 200;30: 56-67.

- Cook R.A., O’Malley M.J. Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Orthop Nurs. 2001;20(4): 30-37.

- Guyer, A.J., Richardson, E.G. Current Concepts Review: Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(2): 256-264.

- Detrembleur C. Leemrijse T. The effects of total ankle replacement on gait disability: analysis of energetic and mechanical variables. Gait Posture. Feb 2009. 270-274.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Once an ankle has reached the point where total arthroplasty is warranted, there is not much the Physical Therapist can do pre-surgery other than general strengthening for better post-op recovery. After the surgery the PT will need to focus on joint stability & strength, pain & edema, general medical management, ROM, and balance/gait control. As the ankle is the most inferior joint in direct weight-bearing of the torso and limbs, utmost concern should be noted when working within the gait & locomotion arena.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1VwHIhVo4vdyrtaEe-clEgaFBaRMj3ptrl0HYJ5qSaXRFbmg-8|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Cook R.A., O’Malley M.J. Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Orthop Nurs. 2001;20(4): 30-37.

- ↑ Doets, C., Brand, R., Nelissen, R. Total Ankle Arthroplasty in Inflammatory Joint Disease with Use of Two Mobile-Bearing Designs. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2006;88:1274-1284.

- ↑ Haddad, S. et all. Arthroplasty vs Arthrodesis: Intermediate and Long-Term Outcomes of Total Ankle Arthroplasty and Ankle Arthrodesis A Systematic Review of the Literature. THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY. 2007;89:1899-1905.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Saltzman, C.L., McIff, T.E., Buckwalter, J.A., Brown, T.D. Total Ankle Replacement Revisited. JOSPT. 2000;30: 56-67. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Saltzman, CL" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Goodman, C., Snyder, T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Huber L. Clinical review Ankle Replacement. Cinahl Information Systems.2010

- ↑ San Giovanni T.P., Keblish D.J., Thomas W.H., Wilson M.G. Eight-year results of a minimally constrained total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27(6):418-426

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Lee KB, Park YH, Song EK, Yoon TR, Jung KI. Static and dynamic postural balance after successful mobile-bearing total ankle arthroplasty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Apr 2010: 519-522.

- ↑ Valderrabano V., Nigg B.M., von Tscharner V., Frank C.B., Hintermann B. Total ankle replacement in ankle osteoarthritis: an analysis of muscle rehabilitation. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(2):281-291.

- ↑ Dyrby C., Chou L.B., Andriacchi T.P., Mann R.A. Functional evaluation of the Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement. Foot Ankle Int.2004;25(6):377-381.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Gill. LH. Challenges in Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(4):195-207.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Guyer, A.J., Richardson, E.G. Current Concepts Review: Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(2): 256-264.

- ↑ Cracchiolo A. III, Deorio, J.K. Design features of current total ankle replacements: implants and instrumentation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(9):530-540.

- ↑ Pfeiff C. The Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement (STAR). Orthop Nurs. 2006; 25(1): 30-33.

- ↑ Herr, Mark. otal Ankle Replacement with Dr. Mark Herr [Video]. YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GJl4BD-xzM. Published Jan 19, 2010. Accessed July 11, 2011.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Lagaay PM, Schuberth JM. Analysis of Ankle Range of Motion and Functional Outcome Following Total Ankle Arthoplasty. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 2010: Iss. 49, 147-151.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gougoulias N, Khanna A, Maffulli N. How Successful are Current Ankle Replacements?: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Jan 2010: 199-208.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Buechel FF Sr, Buechel FF Jr, Pappas MJ. Twenty- year evaluation of cementless mobile-bearing total ankle replacements. Department of Orthopaedic Surgery New Jersey Medical School. Jul 2004: 19-26.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Bonnin M, Judet T, Colombier JA, Buscayret JA, Graveleau N, Piriou P. Midterm results of the Salto Total Ankle Prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Jul 2004: 6-18.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Culham EG, Westlake KP, Wu Y. Sensory-specific balance training in older adults: effect on position, movement, and velocity sense at the ankle. Phys Ther. May 2007: 560-568.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Detrembleur C. Leemrijse T. The effects of total ankle replacement on gait disability: analysis of energetic and mechanical variables. Gait Posture. Feb 2009. 270-274.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 DePuy Orthopaedic Inc. My ankle replacement. http://www.myanklereplacement.com/DePuy/docs/Ankle/Replacement/Rehabilitation/following_ars.html. Updated 2011. Accessed July 14, 2011.