Bladder Cancer

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

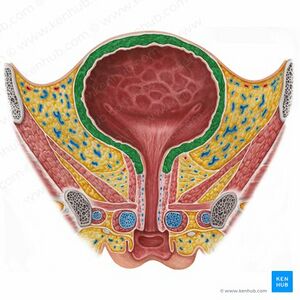

The bladder wall is composed of four layers, each with its unique structure and function.

- The innermost layer is the urothelium, also known as transitional epithelium, which lines the bladder, kidneys, ureters, and urethra. This layer consists of specialized cells termed urothelial or transitional cells.

- Surrounding the urothelium is the lamina propria, a connective tissue layer that provides support and structure.

- Surrounding the lamina propria is the detrusor muscle or muscularis propria. This layer is made up of smooth muscle fibers arranged in various longitudinal and circular patterns, which are responsible for the bladder's contraction and expansion.

- Serosa is the outermost layer of the bladder wall formed from the peritoneum. This is followed by a layer of fatty connective tissue that separates the bladder from other nearby organs.

Bladder cancer (BCa) is one of the most common cancers worldwide, it's incidence varies globally and is expected to rise in the next decade. In addition, the most common malignancy of the urinary tract. Is almost three times greater in more developed areas

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Bladder cancer accounts for as the most common tumors world wide it the 11th most prevalent cancer[1]. It is about 5% of all new cancer cases in the United States, and there is approximately 550 000 new cases being diagnosed every year till 2018[1]. This cancer often recurs and progresses despite treatment, leading to significant healthcare costs, estimated at €4.9 billion in the European Union in 2012. There is a high incidence rates in Europe, Northern America, and Western Asia, low rates in parts of Africa. In addition, Mortality rates vary similarly, with the highest in Western Asia and Northern Africa[2]. Compared to the previous stud in 2012 there is a decreases in mortality rate that may be due to earlier diagnosis, improved endoscopic systems, and better therapies[2]. The incidence rate for both gender was 9.6 per 100 000 for males and 2.4 per 100 000 for females.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Bladder cancer (BC a) begins when cells in the bladder undergo genetic mutations. That cause cells to grow and divide uncontrollably, overriding the mechanisms that normally regulate their growth and death. The uncontrolled growth of these mutated cells leads to the formation of a tumor, a mass of cancerous cells. In the bladder, these tumors typically start in the urothelial cells lining the inside of the bladder.

The initial step in the development of bladder cancer involves the loss of genetic material on chromosome 9, known as loss of heterozygosity (LOH). This leads to the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, contributing to the transformation of normal bladder cells into cancerous ones. Specifically, deletions in both the long arm (9q) and short arm (9p) of chromosome 9 are linked to early stages of bladder cancer, such as dysplasia and carcinoma in situ (CIS), which can progress to more invasive cancer. A key region on 9p21, responsible for encoding important tumor-suppressing proteins (p14ARF, p15, and p16), and is often completely deleted in transitional cell carcinoma, a common type of bladder cancer, leading to the loss of these critical tumor suppressor genes. This genetic alteration plays a significant role in the onset and progression of bladder cancer[3].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Patient with bladder cancer usually is presented with asymptomatic hematuria that is visible or even by microscobic that is the most common presentation.

- Other urinary voiding symptoms may present like; urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia, or dysuria.

- If the tumor is located close to the bladder neck or urethra, obstructive symptoms like a weakened or interrupted urine flow, the need to strain, or a sensation of not fully emptying the bladder might occur[4].

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Geographic location (whites to be about more 2 times than blacks or Hispanics)

- Age (older age)

- Gender (men more than women)

- Cigarette smoking, estimated to be responsible for half of all BCa cases[5].

- Medications such as cyclophosphamide

- Chronic bladder inflammation, and previous cancer treatments.

- Pelvic radiation[6].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

It suggests that bladder cancer screening could be beneficial for specific populations who are at higher risk. For example, people with aristolochic acid nephropathy (a condition associated with an increased risk of developing cancer, including BCa). In this high-risk group, BCa was diagnosed in 50% of the individuals[7].

- Cystoscopy[8]

- Imaging of the upper urinary tract imaging

- Renal function testing[9]

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Medical Treatment[edit | edit source]

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) immunotherapy is an important treatment for serious bladder cancer. Doctors have been trying to figure out the best amount and timing for this treatment. A study called EORTC-GU found that using less BCG doesn't reduce side effects and that using the full amount for a longer time works better to stop the cancer from coming back. But, there was a shortage of BCG worldwide, so another study named NIMBUS tried using fewer treatments[7].

Chemotherapy should as an additional therapy to radical cystectomy that is with extended lymphadenectomy[6].

Surgical Treatment[edit | edit source]

Transurethral resection (TURBT) used for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBCa), that is confined to the bladder's mucosa and estimated to be about 75% of diagnosed bladder tumors[6].

Bladder removal (radical cystectomy) often required for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBCa), and estimated to be about 25-30% of cases[4][6].

Physical Therapy Intervention[edit | edit source]

Patients who undergo treatment for bladder cancer by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or cystoscopy often do not engage in enough physical activity before or after intervention and face frequent hospital readmissions because of complications. As a result, it's important to create a physical rehabilitation program. Exercise has been shown to decrease the risk of bladder cancer death by 47%, improve cancer-specific quality of life, reduce fatigue, and enhance fitness. A study found, patients who exercised more than one day per month showed better physical health than those who didn't[10].

Individualized physical rehabilitation program is important especially considering the older age [10]to avoid and eliminate the rate of hospital admission, improve health related quality of life, the program may include; aerobic exercise (moderate intensity (30 min/session), strengthening exercise including endurance training with 2 × 15 repetitions and behavioral support for daily physical activity[11]. In addition, strengthening pelvic floor and abdominal muscles is important[11].

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Teoh JY, Huang J, Ko WY, Lok V, Choi P, Ng CF, Sengupta S, Mostafid H, Kamat AM, Black PC, Shariat S. Global trends of bladder cancer incidence and mortality, and their associations with tobacco use and gross domestic product per capita. European urology. 2020 Dec 1;78(6):893-906.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wong MC, Fung FD, Leung C, Cheung WW, Goggins WB, Ng CF. The global epidemiology of bladder cancer: a joinpoint regression analysis of its incidence and mortality trends and projection. Scientific reports. 2018 Jan 18;8(1):1129.

- ↑ Shin JH, Lim JS, Jeon BH. Pathophysiology of bladder cancer. InBladder Cancer 2018 Jan 1 (pp. 33-41). Academic Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, et al. Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;178(6):2314-2330.

- ↑ van Osch FH, Jochems SH, van Schooten FJ, Bryan RT, Zeegers MP. Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies. International journal of epidemiology. 2016 Jun 1;45(3):857-70.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 DeGEORGE KC, Holt HR, Hodges SC. Bladder cancer: diagnosis and treatment. American family physician. 2017 Oct 15;96(8):507-14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dobruch J, Oszczudłowski M. Bladder cancer: current challenges and future directions. Medicina. 2021 Jul 24;57(8):749.

- ↑ Davis R, Jones JS, Barocas DA, Castle EP, Lang EK, Leveillee RJ, Messing EM, Miller SD, Peterson AC, Turk TM, Weitzel W. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults: AUA guideline. The Journal of urology. 2012 Dec;188(6S):2473-81.

- ↑ Sharp VJ, Barnes KT, Erickson BA. Assessment of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults. American family physician. 2013 Dec 1;88(11):747-54.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Koelker M, Alkhatib K, Briggs L, Labban M, Meyer CP, Dieli-Conwright CM, Kang DW, Steele G, Preston MA, Clinton TN, Chang SL. Impact of exercise on physical health status in bladder cancer patients. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2023 Jan;17(1):E8.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Porserud A, Karlsson P, Rydwik E, Aly M, Henningsohn L, Nygren-Bonnier M, Hagströmer M. The CanMoRe trial–evaluating the effects of an exercise intervention after robotic-assisted radical cystectomy for urinary bladder cancer: the study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC cancer. 2020 Dec;20:1-0.