How to Remember What You Learn

Original Editor - Michael Rowe

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Remembering is a complex cognitive process. In order to memorise something, we must periodically repeat the information that needs to be remembered.[1]

Students are expected to memorise, learn and master vast amounts of new information. While this information is often presented in varied and engaging ways,[2] students often feel overwhelmed by the amount of information. They must decide which information to retain from a never-ending stream of facts.[3] Moreover, teachers tend to assume that students know how to learn, but in reality, a lot of students resort to ineffective learning and study techniques.[2] The Internet and social media have also changed how people receive, retain, and share information.[4] Searching for information online may lead to offloading memory (i.e. using the Internet and other tools as external memory stores[4]) and forgetting.

This article offers strategies to enhance your ability to remember.

Memory[edit | edit source]

Memory is the capacity to store and retrieve information.[5]

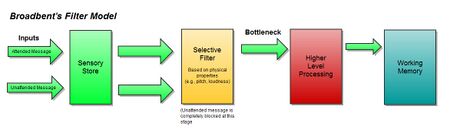

Broadbent Filtering Model[edit | edit source]

The Broadbent Model of Attention is based on the theory that humans cannot consciously attend to all sensory inputs simultaneously.[6] We can only process a limited amount of sensory information at any given time, so only a fraction of the information we are exposed to makes it into our conscious experience of the world. The human brain can filter out most of the incoming sensory information. This is called selective attention, or the ability to focus on a task.

Short-term Memory[edit | edit source]

Short-term memory (STM) is our working memory. This is where we store information for short periods of time, holding it for later processing. We can store around four to seven pieces of information in our STM. These pieces of information are known as chunks. We can group these chunks into larger chunks, which is called chunking.

Chunking is "a kind of information compression that we use to group related information in ways that make it more memorable. By grouping these chunks of related information together, we're able to significantly increase the capacity of working memory."[7] -- Michael Rowe

Memory Trace[edit | edit source]

- An initial memory is called a memory trace

- The memory trace is weak

- It must be reinforced through intentional practice to retain information for a significant period of time

Myths and Realities About Memory[edit | edit source]

- We must re-read a text to remember it: re-reading texts creates an illusion of knowledge because you only recognise the text while reading it.

- Highlighting information in different coloured pens helps you remember it: there is no evidence to support this theory.

- Cramming for a test (i.e. massed practice) is a good way to remember things: this is an ineffective technique for remembering information in the long term.

- Working through the night is a reasonable strategy when preparing for an assessment: sleeping well is essential to encoding memories.

Memory Storage[edit | edit source]

To remember something, we must:

- Step # 1: Hold information in our working memory (short-term memory)

- Step #2: Move information to our long-term memory. This second step occurs in three stages:

- Stage 1: Encoding: converting incoming information into new synaptic connections.

- Effective Learning Rule # 1: Selective attention. Your ability to focus attention improves the likelihood you will encode new information. Setting up your learning environment helps you pay attention to the information that matters.

- Stage 2: Consolidating: memory traces are moved into higher capacity long-term storage.

- Effective Learning Rule # 2: Emotional salience. If the information excites you, moves you, or reminds you of special times, you will more likely encode it.

- Effective Learning Rule # 3: Relevance. If you have a mental model to attach the new information to, you will more likely encode it.

- Effective Learning Rule # 4: Comprehensibility. You're more likely to encode information if it makes sense to you.

- Stage 3: Retrieving: information is retrieved from long-term storage.

- Effective Learning Rule # 5: Retrieval practice. When done regularly, retrieval practice increases the strength of the memory trace. The more frequently you actively recall information, especially in the early stages of memory formation, the better your memories will be. Retrieving information increases the size of the chunks you can encode.

- Stage 1: Encoding: converting incoming information into new synaptic connections.

Process of Forgetting[edit | edit source]

Facts About Forgetting[edit | edit source]

- We forget about 70% of what we've just heard or read

- The last 30% of information fades more slowly

- We quickly forget most of what we pay attention to

- To improve learning, we need to interrupt the process of forgetting

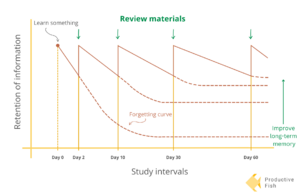

Forgetting Curve[edit | edit source]

The forgetting curve is a graph that shows the average rate at which information fades from memory. This curve indicates the following:

- the half-life of new information is about a week (seven days) unless we spend time reviewing the material

- active retrieval is a simple way to keep a memory for longer periods

Memory Strength[edit | edit source]

Memory strength is the durability of the memory trace left in the brain. The stronger the memory, the longer you can recall it.

Information Recall[edit | edit source]

Sometimes, we have difficulty recalling information acquired just a few hours prior. There are two main explanations for this phenomenon:

- The illusion of knowledge. After re-reading information 3-4 times, you start to anticipate the words and the order in which they appear:

- this does not play any role in helping you to remember what you are reading

- it creates the feeling of familiarity with the text, but it is not knowledge

- you cannot explain the concept in your own words

- re-reading a text is an example of massed practice, and it is the least productive remembering technique

- it is a less cognitively demanding approach to remembering - it only makes you feel like you are learning

- The illusion of explanatory depth. The belief that you understand something when you have environmental cues that help to fill in the gaps in your knowledge:

- recalling information may be impossible without these environmental cues (e.g. the physical setting, the patient you are using equipment on, the medical folder you just reviewed, etc.).

- creates a superficial explanation for knowledge (e.g. using mainstream resources instead of specialised resources to learn about pathology).

Strategies To Remember More[edit | edit source]

"The stronger the memory, the longer we're able to recall it. So, we need to work on increasing the strength of the memory trace."[7] -- Michael Rowe

Four of the most effective strategies for improving the consolidation and retrieval of information are: retrieval practice, distributed practice, interleaved practice, and elaboration.

Retrieval Practice[edit | edit source]

Retrieval, or active recall, is retrieving encoded chunks of information from your long-term memory. It includes answering questions or explaining concepts without referring to the source and using your own words to answer the question.

A simple way to practise retrieval is as follows:

- immediately after a lecture, go through your notes and see how many of the high-level concepts you can recall from memory

- focus your retrieval practice on concepts the lecturer has talked about rather than trying to remember a lot of information about the topic

- once you start reviewing your notes at home, choose a paragraph of text that's linked to the lecture from earlier in the day - read the text once, look away and try to repeat what you read in your own words

- when you are satisfied that you can explain the concept without looking at the source, move on to the next paragraph

Distributed Practice[edit | edit source]

Distributed practice is also called spaced repetition or distributed learning. It includes retrieving information at increasingly longer intervals. One rule of distributed practice is that you must practise retrieving information when you are about to forget it.

"But this is a difficult logistical challenge. [...] You can randomly allocate specific topics to review at different intervals, although you'd essentially be guessing about what to cover at what points in time because you have no way of knowing what you're about to forget."[7] -- Michael Rowe

The following strategies can help with distributed practice:

- use a computer-assistance system - e.g. Anki, a free-spaced repetition flashcard system. Anki uses an algorithm to surface the information you want to remember when the algorithm says you might be about to forget it.

- there is good evidence that 10–15 minutes of daily spaced repetition testing will help you remember more.

Interleaved Practice[edit | edit source]

Interleaved practice is when you mix different but related concepts into your practice of actively recalling information. It helps you integrate existing information with new information by using your brain's ability to identify connections between chunks of information.

The following strategies will help you recall information using interleaved practice:

- choose 2-3 different areas of the same broad topic - for example, you could review knee anatomy, physiology, and functional movements.

- spend one “session” of about 30–45 minutes to work through each topic, explicitly looking for relationships between these subtopics.

- consolidate your understanding by asking the following questions:

- Where do they connect? What areas in each subtopic seem most important relative to the other subtopics? How do they influence each other?

Elaboration[edit | edit source]

Elaboration is the practice of explaining and expanding on concepts you recall from memory, using your own words and without referring to the source material:

- it is a strategy for connecting new information to existing information

- it creates a relationship between variables that connects concepts

- it is a conversation with the author, where you ask and answer questions

Workflow for Remembering What You Have Learned[edit | edit source]

Daily workflow should take no longer than two hours and include the following steps:

- create a habit of reviewing your work daily

- establish a cue that reminds you it is time to review your work - e.g. an hour before dinner

- set up your environment to avoid interruptions and distractions

- review and expand your daily notes

- find additional information through reading

- write with the aim of achieving an important learning objective

- include concepts from the day's lectures into your retrieval practice and add them to your spaced repetition system

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Rozenblit L, Keil F. The misunderstood limits of folk science: an illusion of explanatory depth. Cogn Sci. 2002 Sep 1;26(5):521-562.

- Want to Remember Everything You'll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Kiswardhani AM, Ayu M. Memorization Strategy During Learning Process: Students' Review. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning. 2021 Dec 31;2(2):68-73.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McGuire SY. Teach yourself how to learn: Strategies you can use to ace any course at any level. Taylor & Francis; 2023 Jul 3.

- ↑ Bhattacharjee R, Mahajan G. Learning what to remember. Proceedings of The 33rd International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory in Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 2022; 167:70-89.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wang Q. Memory online: introduction to the special issue. Memory 2022; 30(4): 369-374.

- ↑ Zlotnik G, Vansintjan A. Memory: An Extended Definition. Front Psychol. 2019 Nov 7;10:2523.

- ↑ Mcleod S.Theories Of Selective Attention In Psychology. Available from https://www.simplypsychology.org/attention-models.html [last access 7.10.23]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rowe M. How to Remember What You Learn Course. Plus, 2023.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 THE FORGETTING CURVE: WHY WE FORGET AND HOW TO REMEMBER (2023). Available from https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/what-is-the-forgetting-curve [last access 25.11.2023]