Low Back Pain and Pelvic Floor Disorders

Original Editors - Jenny Nordin, Jacqueline Keller, Chelsey Walker, Katie Schwarz as part of the Texas State University's Evidence-based Practice project.

Lead Editors - Katie Schwarz, Chelsey Walker, Vidya Acharya, Jacqueline Keller, Jenny Nordin, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Admin, Joshua Samuel, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Jeremy Brady, George Prudden, 127.0.0.1 and Rachael Lowe

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Low back pain (LBP) is a condition of localized pain to the lumbar spine with or without symptoms to the distal extremities whose aetiology is commonly unknown.[1] The link between LBP and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), particularly in women, is becoming evident in the literature, however, characteristics that define this correlation have yet to be established[2]. Pelvic floor disorders (PFD) occur when the muscles that comprise the pelvic floor fail to properly contract, which can adversely cause urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, fecal incontinence, or other sensory and emptying abnormalities of the lower urinary and GI tracts.[3] Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) is multifaceted and can be characterized by parameters such as weakness, poor endurance, excessive tension, shortened length and overactivity.[2] Current evidence shows that individuals with low back pain have a significant decrease in pelvic floor function compared to individuals without low back pain.[4]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions; approximately 70-80% of the population will experience at least one episode of LBP during his/her lifetime. Trauma, disease and even poor postural habits are some of the myriad causes of LBP, however, only about 15% of cases can be attributed to a specific cause. Studies show a poor correlation between the pathology and associated pain and disability.[4]

Over 25% of all women and more than a third over the age of 65 experience PFD. The true prevalence of PFD is underestimated for several reasons: heterogeneity in study populations, lack of standardized definitions, and under-reported symptoms due to the sensitive nature. Even though PFD is a physiological problem, the psychosocial impact can be much more detrimental to the patient’s quality of life. Chronic health problems associated with PFD are estimated to increase by 50% over the next 30 years due to the increasing numbers of women reaching age 65.[5] PFD does not typically have one specific cause. The development of PFD most likely involves anatomical, physiological, genetic, reproductive and lifestyle components.[1][5]

The major risk factors are

- pregnancy/childbirth,

- age,

- hormonal changes,

- obesity,

- lower UTI, and

- pelvic surgery.

A longitudinal study on younger, middle-age and older women reported that women with pre-existing incontinence, gastrointestinal problems, and breathing disorders were more likely to develop LBP than women without such problems. [6] This was considered to be a result of changes in morphology and altered postural activity of the trunk muscles including muscles of respiration and continence which provide mechanical support to the spine and pelvis[7].

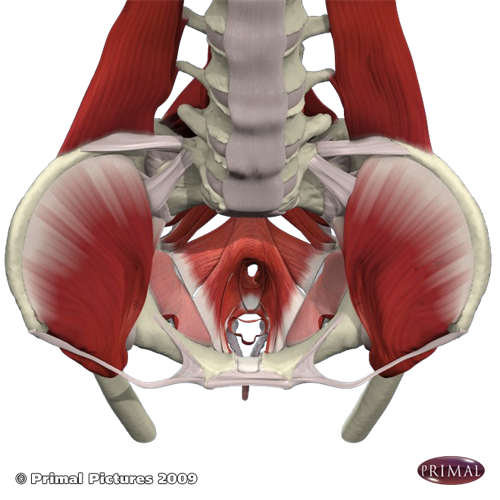

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Lumbopelvic Stability System[edit | edit source]

Bone and ligament structures, muscle compression forces and nervous system control all contribute to lumbopelvic stability. The bone and ligament structures include the lumbar vertebrae and supporting ligaments, the pelvis, symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints. This arrangement transfers weight from the upper body through the lumbosacral spine and across the pelvis to the femoral heads. The diaphragm, transversus abdominis, PFM and multifidus work synergistically to influence posture through intra-abdominal pressure regulation and thoracolumbar fascial tension. The nervous system evaluates the requirements of lumbopelvic control, determines the current status of the region and enacts strategies to meet those functional demands.[8]

The pelvic floor forms the inferior border of the abdomino-pelvic cavity.[5] It supports the abdomino-pelvic organs and the PFM are the only transverse load-bearing muscle group in the body. These muscles function as a unit instead of individually contracting. They play an important role in maintaining and increasing intra-abdominal pressure during functional tasks such as lifting, sneezing, coughing, and laughing to prevent urinary and fecal incontinence. The PFM, along with the deep abdominals and multifidus, use a feed-forward mechanism to stabilize the trunk and control intra-abdominal pressure in response to trunk perturbations.[4][7]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Some characteristics of patients who present with LBP along with pelvic floor disorders:

- Women of middle to older age

- Vaginal delivery (risk increases with multiple deliveries)[3]

- Obesity[5]

- Lumbopelvic pain

- Incontinence

- Chronic Constipation

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Dysparaunia (painful intercourse)[2]

Many women with pelvic core neuromuscular system (PCNS) dysfunction present with a posterior pelvic tilt and decreased lumbar lordosis. Studies suggest that pain in the sacroiliac region may decrease motor control of the PFM.[4] Men can also have disorders of the pelvic floor, however due the anatomy of the male pelvis, it is less common. The male pelvis is more densely packed which allows for faster proprioceptive overflow and muscle recruitment.[9]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

PFD and LBP are difficult to diagnose because they present many challenges due to poor association between pathophysiology, poor patient reported signs and symptoms and anatomical evidence.[5]

- Cauda Equina Syndrome

- Sexual dysfunction.

- Urinary Tract Infection

Examination[edit | edit source]

History [edit | edit source]

Make sure to take a thorough history, clear any red flags, and ask the patient how signs/symptoms have affected his/her function. The following questions can be used to determine if the patient is experiencing any signs/symptoms of PFD.

- How often do you urinate? (Normal – every 2-4 hours or 6-8 times a day)

- Do you ever have urine leakage during activities such as coughing, sneezing, laughing, or exercise?

- Do you ever have urine leakage associated with sudden strong urge?

- Do you have trouble reaching the toilet in time?

- Have you ever lost bowel control?[9]

Evaluation of LBP should begin with completion of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI); based on the patient’s score a treatment based classification system or an impairment-based approach should be used to determine the best intervention.

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

- Observation of posture

- Palpation

- Neurological screen

- Lumbar and hip AROM

- Joint mobility assessment of the lumbar spine

- Clear the hip for involvement (Scour Test, FABER) The cross-sectional study[2] by Dufour et al corroborates previous research suggesting the potential utilization of a Forced FABER test as a predictive test for the presence of pelvic floor tenderness, a parameter of PFD.

- Assess the sacroiliac joint for involvement (Posterior Shear Test, Gaenslen's Test)

The majority of this patient profile (LBP and PFD) will most likely benefit from stabilization interventions. Based on the patient’s primary complaints, it may or may not be necessary to proceed with a full pelvic floor examination.

- A full pelvic floor exam should include:

- Vaginal palpation - scored qualitatively either as correct or incorrect muscle contraction, a digital pelvic examination helps to better understand the correlation between lumbopelvic pain and pelvic floor muscle function. The presence of pelvic floor tenderness was the most pervasive finding in the study[2] , followed by pelvic floor weakness

- Transabdominal ultrasound to assess the quality of voluntary and involuntary PFM and TrA muscle activation

- Grading of PFM strength should be done using a perineometer and/or needle EMG to provide quantitative data about PFM contractions [4][7][10]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Pharmacological Management[edit | edit source]

Pharmacotherapy addresses the incontinence issues instead of targeting the overlying issue of PFD. The aim of these medications is to increase urethral closure pressure by targeting striated and smooth muscles of the urethra.[11] Some patients with LBP may choose to use pain medications or corticosteroid injections to relieve symptoms, however, these therapies do not address PFD nor the underlying problem of LBP.

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Surgery is indicated for women with LBP and PFD who have not benefited from conservative treatments such as physical therapy and have symptoms that significantly impact their daily life.

Surgical interventions to address PFD:

- Pubovaginal Sling Procedure

- Implantation of an artificial urinary sphincter

- Midurethral sling procedure[12]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy treatment modalities include pelvic floor training, manual therapy, biofeedback, movement patterning and behavioral modifications. Manual therapy and biofeedback are used to increase awareness of the pelvic floor and improve the patient’s ability to contract and relax the muscle in addition to strengthening it.

Pelvic floor muscle control is key to preventing urinary incontinence and treating pelvic pain. Pelvic floor dysfunction can be treated by strengthening and improving awareness and control of pelvic floor muscles[13]. Combination of PFMT and biofeedback has shown improved results compared to PFMT alone, and some studies find that electrical stimulation can augment the benefit of biofeedback and PFMT[14].

The study by Xia B et al [15] shows that pelvic floor exercises in combination with routine treatment provide significant benefits in terms of pain relief and disability over routine treatment alone. The pelvic floor can be facilitated by co-activating the abdominals and vice-versa. The abdominals contract in response to a pelvic floor contraction command and the PFM contract in response to a "hollowing or bracing" abdominal command.[7][16]

Randomised control trial[7] carried out on 20 women with chronic LBP, comparing routine physiotherapy with additional PFM training showed greater improvement in PFM strength and endurance along with significant reduction in pain and functional disability, but no significant difference was found between the two groups. It seems that the PFM exercise combined with routine treatment was not superior to routine treatment alone in patients with chronic LBP.

Current evidence supports the preceding exercise protocol; each exercise protocol has the common goal of regaining neuromuscular control of the pelvic floor and deep abdominal muscles in a functional matter.[17] There is also strong evidence for PFM training as a conservative treatment for stress urinary incontinence.[8]

Exercise Progression to Address PFD/LBP:

| Stage | Process | Goal | Dosing |

|

Diaphragmatic Breathing |

The pt is seated with upright posture, one hand on chest, other on stomach (for self awareness); the pt expands his/her stomach while breathing in. |

To minimize ribcage elevation and increase intra-abdominal pressure. This creates a slight stretch on abdominal muscles, enhancing the contractile force and promoting a stronger PFM contraction. |

consistent and correct breathing pattern through out daily activities |

|

Tonic Activation |

The pt places his/her fingers medial to ASIS for tactile feedback. The pt activates the TrA, which influences the PFM to co-contract. |

To promote a gentle and prolonged muscle hold of the PFM through the TrA co-contraction mechanism |

5reps 5xday; gradually increase to 30-40 sec holds |

|

Muscle Strengthening |

The pt, in supine, performs the abdominal drawing in maneuver (ADIM) and maintains a strong hold while pulling up the PFM as far as possible as if to stop the flow of urine. |

To strengthen the PFM to decrease urinary leakage and strengthen abdominal muscles to promote spinal stability |

patient should hold for 3-5sec; count out loud |

|

Functional Expiratory Patterns |

The pt sits upright, and initiates a sustained nose blow. The pt should self evaluate PFM activation during expiration. |

To retrain the PFM to activate in response to functional stresses (ie - nose blowing, coughing, sneezing) |

repeat 5 times |

|

Impact Activities |

Progress the pt to his/her functional high impact activity while maintaining abdominal and PFM contraction. (ie - running, exercise, lifting objects) |

To transfer newly learned activation patterns into functional activities, once the pt achieves coughing/sneezing without loss |

specific to each patient |

Lumbar Stabilization Exercises:

| Transversus Abdominis |

Abdominal bracing Bracing with heel slides Bracing with leg lifts Bracing with bridging Bracing in standing |

8s hold x 20reps 4s hold x 20reps 4s hold x 20reps 8s hold x 30reps 8s hold x 30reps |

| Multifidus |

Quadruped arm lifts with bracing Quadruped leg lifts with bracing Quadruped alt. arm/leg lifts with bracing |

8s hold x 30reps 8s hold x 30reps 8s hold x 30reps |

| Oblique Abdominals |

Side planks with knees flexed Side planks with knees extended |

8s hold x 30reps 8s hold x 30reps |

| [20] | [21] |

| [22] | [23] |

Treatment for this patient should also include education on healthy lifestyle habits to promote optimal functioning of the lumbopelvic stability system. Examples of these habits include good posture, maintenance of a healthy body weight, proper diet, routine exercise, and refraining from smoking.

Resources[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

|

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and LBP: Diagnosis and Management

This presentation, created by Rico Buentello, Christine Castillo, Martini Castaneda, and Dylan Cooke; Texas State DPT Class. |

|

Relationship Between LBP and Disorders of the Pelvic Floor

This presentation, created by Ashley Aikman, Delesa Monroe, Ashley Trotter, Michael Landin; Texas State Class of 2014, Evidence-based Practice projects for PT7539 Ortho Spine course. Relationship Between LBP and Disorders of the Pelvic Floor / View the presentation |

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Transabdominal ultrasound has proven that the PFM and trunk musculature co-contract to provide stability to the lumbar spine and pelvis. Lack of neuromuscular control in the PFM can be associated with trunk instability, which results in LBP.[4][6][24][8][9][25][26]

It is important for the physical therapist to consider pelvic floor dysfunction when evaluating and treating patients with LBP. Although recent research has made many gains in relating LBP and PFD, much more progress is needed to definitively establish the relationship between the two conditions and identify successful intervention techniques.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Eliasson K, Elfving B, Nordgren B, Mattsson E. Urinary incontinence in women with low back pain. Manual Therapy. June 2008;13(3):206-212.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Dufour S, Vandyken B, Forget MJ, Vandyken C. Association between lumbopelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in women: A cross sectional study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2018 Apr 1;34:47-53. (PDF) Association between lumbopelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in women: A cross sectional study. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321710141_Association_between_lumbopelvic_pain_and_pelvic_floor_dysfunction_in_women_A_cross_sectional_study [accessed Nov 28 2018].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Jama. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311-6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Arab AM, Behbahani RB, Lorestani L, Azari A. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle function in women with and without low back pain using transabdominal ultrasound. Manual therapy. 2010 Jun 1;15(3):235-9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Davis K, Kumar D. Pelvic floor dysfunction: a conceptual framework for collaborative patient‐centred care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003 Sep;43(6):555-68.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Smith M, Russell A, Hodges P. Do incontinence, breathing difficulties, and gastrointestinal symptoms increase the risk of future back pain?. Journal of Pain. August 2009;10(8):876-886.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Mohseni-Bandpei M, Rahmani N, Behtash H, Karimloo M. The effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise on women with chronic non-specific low back pain. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies. 2011;15(1):75-81.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Grewar H, McLean L. The integrated continence system: a manual therapy approach to the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Manual Therapy. October 2008;13(5):375-386.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Christie C, Colosi R. Paving the way for a healthy pelvic floor. IDEA Fitness Journal. May 2009;6(5):42-49. (Accessed on 26/11/2018)

- ↑ Bo K, Sherburn M. Evaluation of female pelvic-floor muscle function and strength. Physical Therapy. March 2005;85(3):269-282.

- ↑ Hashim H, Abrams P. Pharmacological management of women with mixed urinary incontinence. Drugs. April 2006;66(5):591-606.

- ↑ McKertich K. Urinary incontinence - Procedural and surgical treatments for women. Australian Family Physician. March 2008;37(3):122-131.

- ↑ Physical therapy program for pelvic floor dysfunction meets individual needs UCLA heath. https://www.uclahealth.org/workfiles/clinical_updates/urology/15v1-03_pelvicfloor_fnlHR.pdf (accessed on 29/11/18)

- ↑ Arnouk A, De E, Rehfuss A, Cappadocia C, Dickson S, Lian F. Physical, complementary, and alternative medicine in the treatment of pelvic floor disorders. Current urology reports. 2017 Jun 1;18(6):47.

- ↑ Bi X, Zhao J, Zhao L, Liu Z, Zhang J, Sun D, Song L, Xia Y. Pelvic floor muscle exercise for chronic low back pain. Journal of International Medical Research. 2013 Feb;41(1):146-52.

- ↑ Sapsford RR, Hodges PW, Richardson CA, Cooper DH, Markwell SJ, Jull GA. Co‐activation of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles during voluntary exercises. Neurourology and Urodynamics: Official Journal of the International Continence Society. 2001;20(1):31-42.

- ↑ O'Sullivan P, Beales D. Changes in pelvic floor and diaphragm kinematics and respiratory patterns in subjects with sacroiliac joint pain following a motor learning intervention: a case series. Manual Therapy. August 2007;12(3):209-218.

- ↑ Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Manual Therapy. February 2004;9(1):3-12.

- ↑ Hicks G, Fritz J, Delitto A, McGill S. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. September 2005;86(9):1753-1762.

- ↑ walkercs10. Transversus Abdominis. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w42g_lCa_HA

- ↑ walkercs10. Multifidus. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=khIF3k8EhwQ

- ↑ walkercs10.Oblique Abdominals. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5R8X8PC4WQ

- ↑ Physio Fitness | Physio REHAB | Tim Keeley.Correct core activation - engage your TA and pelvic floor! | Feat. Tim Keeley | No.18 | PhysioREHAB.Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0HzXm3epAU

- ↑ Smith M, Russell A, Hodges P. Do incontinence, breathing difficulties, and gastrointestinal symptoms increase the risk of future back pain? Journal of Pain. August 2009;10(8):876-886.

- ↑ Pool-Goudzwaard A, Slieker ten Hove M, Stoeckart R, et al. Relations between pregnancy-related low back pain, pelvic floor activity and pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology Journal And Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. November 2005;16(6):468-474.

- ↑ Smith M, Russell A, Hodges P. Disorders of breathing and continence have a stronger association with back pain than obesity and physical activity. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. March 2006;52(1):11-16.