Placebo Effect

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Melissa Coetsee, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A placebo is a "physiologically inert substance or sham intervention (psychological, physical or mechanical) which produces beneficial effects independent of any direct therapeutic effects".[1] The positive effects occur as a result of a patient's expectations rather than as a result of a causative ingredient. A placebo can be for example be a saline solution, sterile water, or sham surgery.[2]

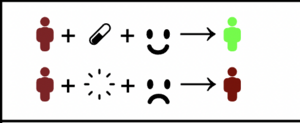

The Placebo effect is a psychobiological response that influences clinical outcomes.[3] It refers to the positive outcomes that occur as a result of psychosocial factors and expectancies, rather than the intervention applied. It can occur when placebos are administered, but it can also enhance the effects of active interventions/substances.[3]

The negative counterpart of the placebo effect, is the nocebo effect. This refers to the adverse outcomes that occur as a result of patient expectations and subconscious learning.

History[edit | edit source]

Placebos have been in use since antiquity and may have been significant in improving health and quality of life when little was known about the aetiology of most illnesses. The emergence of placebo-controlled clinical trials in the 1940s reintroduced the placebo effect to the modern day[4]. In the past, the placebo effect was only recognised when administering placebos (inactive treatment). Since these placebos were known to have no medical significance and was considered “fake”, any improvements in clinical outcomes could be attributed to the placebo effect. This has been very important in clinical trials in order to discern whether observed improvements can be attributed to a specific intervention.

Over the past 30 years, there has been an increase in research on the placebo effect using a neuroscientific approach, with an interest in the identification of several biological mechanisms of the placebo. An important contribution of neuroscience has been to highlight the important role of psychobiological factors in therapeutic outcomes, be they drug-related or not[5].

Through research it became clear that the placebo effect is influenced by various factors and that any treatment (real or fake) can be modulated by it. The expectations of the patient play a large part here, with a higher belief in the treatment enhancing the beneficial response.[2]Placebo effects also occur when placebos are given after active medications, resulting in dose-extending effects.[3]There has also been increasing awareness that various psychosocial factors (words, context, beliefs, communication etc.) influence the placebo effect and can thus be harnessed to enhance the treatment effects of non-placebo interventions.

The Meaning Response[edit | edit source]

Many authors have argued that the term "Meaning response" should rather be used to refer to any treatment effects that occur as a result of the meaning attached to it (i.e. expectations and beliefs). This term then encompasses both positive and negative (placebo and nocebo) effects that can occur as a result of expectations and subconscious learning.

Mechanism[edit | edit source]

Two theories have been proposed to explain the placebo effect:

- Conditioning theory: that the placebo effect is a conditioned response

- Mentalistic theory: sees the patient's expectation as the primary cause of the placebo effect

The current understanding it that both these theories are at place, and that genetics also plays a role. It remains to be fully understood how conditioning and expectation are able to activate memory loops in the brain that reproduce the expected biological responses[6].

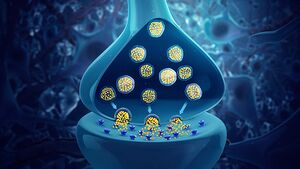

When someone expects a treatment to be beneficial, various neurobiological systems are activated[7]:

- Descending pain-modulation: Endogenous opioid system and endocannabinoid system

- Cortical centres that reduce anxiety: mainly the amygdala an its functional network

- Reward mechanisms: Mainly the dopaminergic system

This is the case for placebo-dopamine in Parkinson's disease, for placebo-analgesics or antidepressants, and for placebo-caffeine in the healthy subject.

Contributing Factors[edit | edit source]

These neurobiological effects are influenced by various factors. As Colloca (2019) puts it, the placebo effect is:

"Partially determined by genetic factors, maintained through learning mechanisms and sustained by the cognitive dynamic integration of expectations surrounding the therapeutic environment, patient-clinician relationship and the act of administering an intervention." [3]

It is interesting to note, that when participants in clinical trials are told that the treatment they receive is a placebo, beneficial effects are still observed. This indicates that the placebo effect is not only influenced by conscious expectancies, but also by subconscious learning and conditioning.[3]

Placebo Effect in Healthcare Research[edit | edit source]

Pharmacological[edit | edit source]

This refers to inactive pills that are given to control groups in clinical trials in order to determine whether the active pills are more effective than placebo.

- Brain imaging has demonstrated that placebos can mimic the effect of active drugs and activate the same brain areas.

- Pharmacological studies have shown that placebos mimic the action of active treatments, especially pain medications[3]

- The placebo effect results in the release of endogenous opioids and non-opioids[3]

- Migraine medication: Medications that are labelled, produce better outcomes than unlabelled medications. If active medication is labelled as a placebo, it is just as effective as a placebo pill labelled with the medication name.[10]

Psychological & Verbal[edit | edit source]

This includes belief manipulation and expectation optimisation, as well as more subtle aspects of word choice, confidence, trust, communication and contextual factors.

- A pre-surgery expectation optimization program, applied to patients scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting, resulted in lower disability scores at 6-month post-surgery follow-ups[3]

- Postural stability: Postural control outcomes improve in response to positive performance expectation[1]

Manual Therapy[edit | edit source]

Manual therapy as applied by physiotherapists in the rehabilitation setting are a part of rehabilitation rather than applied in isolation. The context of the treatment including the technique, the provider, the participant, the environment, and the interaction between these factors may contribute to patient outcomes. The effects of manual therapy are likely related to multiple mechanisms, including the placebo effect. Many of the neurophysiological responses associated with manual therapy and considered pertinent in the clinical outcomes are also observed in placebo studies unrelated to manual therapy. Placebo responses may account for some of the changes in clinical outcomes observed in response to manual therapy[11].

- Placebo-related hypoalgesia may be enhanced by factors related to negative mood, expectation, and conditioning, and manual therapists should be aware of these influences and take steps to maximize their benefits during treatment (not meaning that we should purposefully deceive our patients by knowingly promoting the benefits of inert or ineffective interventions).

- Manual therapists may strengthen the treatment effects of evidence-based interventions when they embrace the placebo response.[11]

Sham Surgery[edit | edit source]

Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: The New England Journal of Medicine published a trial showing that sham surgery can be as good as the real thing. The subjects were candidates for knee surgery, with a torn meniscus and debilitating pain. They underwent surgery in the operating room with surgeons who performed either a meticulous repair of the torn cartilage or a charade. Incisions were made, and closed, with no other intervention. In the operating theatre, the doctors and nurses passed instruments, made surgical sounds, and pretended to do surgery for as long as the procedure would normally take. Both surgeries worked, with subjects who underwent the fake procedure experiencing just as much improvement in pain and activity as those whose meniscus was actually repaired.[12]

Tendinopathy: Sham surgery (placebo) trials are the gold standard against which to judge the effect of surgery on clinical conditions (eg tendinopathy). In 12 eligible randomised controlled trials in patients with various tendinopathies, surgery was not superior to sham surgery in patients with tendinopathy in the midterm and long term. Studies advocate that healthcare professionals who treat patients with tendinopathies should reserve surgery for selected cases and only after a sufficiently long course (12 months) of evidence-based loading exercise has failed[13].

Other surgeries that have been shown to be no better than "sham" surgery[14]:

- Arthroscopic subacromial decompression

- Arthroscopic debridement of the knee

- Vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fractures

- Intradiscal electrothermal therapy

Parkinson's Interventions[edit | edit source]

Studies have shown people with Parkinson’s experience a significant placebo effect. Patient characteristics that affect placebo include patients' expectations of good outcomes, genetic variants, and personality. Exactly how placebos work and why they may have a potentially larger impact on Parkinson’s isn’t clear. But it likely has to do with dopamine, the brain chemical that decreases in Parkinson’s. Brain imaging studies show that placebos stimulate the release of dopamine, which plays a role in the brain’s reward system[15].

Clinical Implications[edit | edit source]

Placebo effects are not limited to clinical trials - any treatment or intervention is significantly modulated by the placebo effect in the clinical setting.[3]Healthcare workers have the power to enhance clinical outcomes by paying attention to their communication, attitudes, confidence and competence.

The placebo effect can be used to enhance the real-world effectiveness of interventions, and in addition the adverse outcome of nocebo effects should be minimised.[7]

A Little Irrelevancy[edit | edit source]

- I'm addicted to placebos. I could quit but it wouldn't matter.

- In my whole life I’ve only ever been to two concerts. I’ve seen Placebo, and I’ve seen The Cure. They were just as good as each other

- On my way home from work today I was listening to Placebo. I thought I was listening to something else, but obviously, I was in the control group.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Society for Interdisciplinary Placebo Studies: an international association of scholars who share the goal of understanding the placebo effect by promoting communication and cooperation between research centres and scholars.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Russell K, Duncan M, Price M, Mosewich A, Ellmers T, Hill M. A comparison of placebo and nocebo effects on objective and subjective postural stability: a double-edged sword?. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2022 Aug 18;16:967722.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Byjus. Placebo effect. Available from:https://byjus.com/biology/placebo-effect/ (accessed 21.4.2022)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Colloca L. The placebo effect in pain therapies. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2019 Jan 6;59:191-211.

- ↑ Munnangi S, Sundjaja JH, Singh K, Dua A, Angus LD. Placebo Effect. 2022 Jun 23. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- ↑ Benedetti F, Frisaldi E, Shaibani A. Thirty years of neuroscientific investigation of placebo and nocebo: the interesting, the good, and the bad. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2022 Jan 6;62:323-40.

- ↑ Haour F. Mechanisms of the placebo effect and of conditioning. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12(4):195-200.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hohenschurz-Schmidt D, Thomson OP, Rossettini G, Miciak M, Newell D, Roberts L, Vase L, Draper-Rodi J. Avoiding nocebo and other undesirable effects in chiropractic, osteopathy and physiotherapy: An invitation to reflect. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2022 Oct 21:102677.

- ↑ Biogen . Helping You Understand the Placebo Effect. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RhG_ySxhDA[last accessed 25/1/2023]

- ↑ BrainFacts.org. The Neuroscience Behind the Placebo Effect. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REaiu-7wRvs [last accessed 25/1/2023]

- ↑ Dorow B. Words that Hurt, Words that Heal. [PowerPoint presentation]. Kaiser Permanente Persistent Pain Fellowship.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, George SZ, Robinson ME. Placebo response to manual therapy: something out of nothing? Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2011;19(1):11-19.

- ↑ Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2515-24.

- ↑ Challoumas D, Clifford C, Kirwan P, Millar NL. How does surgery compare to sham surgery or physiotherapy as a treatment for tendinopathy? A systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine. 2019 Apr 1;5(1):e000528.

- ↑ Louw A, Diener I, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Puentedura EJ. Sham surgery in orthopedics: a systematic review of the literature. Pain Medicine. 2017 Apr 1;18(4):736-50.

- ↑ Lou JS. Placebo responses in Parkinson's disease. International Review of Neurobiology. 2020 Jan 1;153:187-211.