Cognition and Perceptual Disorders: Difference between revisions

Romy Hageman (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Romy Hageman (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 00:32, 29 June 2024

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Cognition is the process of acquiring knowledge[1]. It includes reasoning, memory, awareness, judgment, and intuition. Some authors include executive function under cognition too, such as problem-solving, planning capacity, recognition of errors, and abstract thinking[2][3]. Executive functions are often classified as higher-level cognitive functions or metacognitive functions[4].

Perception is the integration of sensations into information that is meaningful in terms of psychology[5]. It is the ability to choose the stimuli that need attention and action, to integrate them, and to interpret them.

Perception and sensation are not the same and should not be confused with each other. The sensation is defined as the awareness of stimuli through eyes, ears, nose, etc., internal receptions, or the peripheral cutaneous system[6]. Perception, however, is a more complex process involving the interpretation of these sensations.[7]

Perception disorders[edit | edit source]

Body image impairments[edit | edit source]

Unilateral Neglect[edit | edit source]

Unilateral neglect is reported nearly in 25% of the patients who are referred for rehabilitation. It is commonly associated with right parietal lesions[8][9].

Rehabilitation- The major goal here is to improve the attention of the neglected side along with proprioception and kinesthesia. The recent techniques of rehabilitation are neck muscle vibration, virtual reality, limb activation training, mental imagery training, TENS, Eye patching, prism adaptation, vestibular rehabilitation, and mirror therapy[10][11][12][13][14][15][16].

[17]A short video about hemineglect.

Neck Muscle vibration[edit | edit source]

Somatosensory stimulation in the form of neck muscle vibration can be applied on the neck of the patient with unilateral neglect for improved detection of stimuli in the same side (affected side) visual field [18].

Anosognosia[edit | edit source]

It is the denial of illness that may be seen in the patients of head injury[19]. The patients present either lack of concern about the deficit or verbal denial of their illness[20]. They don't realize the benefits of rehabilitation and are not willing to undergo any treatment. Visual field defect, apathy, and unable to identify pictures are common in anosognosia[21]. It is commonly seen in neurological conditions such as Hemiplegia and Alzheimer's disease and has a significant impact on patients, but also on their caregivers[22][23].The occurrence of anosognosia among individuals with Alzheimer's disease is estimated to range from 20% to 80%[24].

[25] An explanation of Anosognosia.

Rehabilitation- Vestibular stimulation has proven effective in anosognosia by enhancing spatial orientation and self-awareness. This involves using vestibular inputs to stimulate the balance organs, helping patients develop a better understanding of their deficits[10].

Asomatognosia[edit | edit source]

There is a lack of awareness of the body structure[26]. The patient even doesn't understand the relationship of body parts with oneself or to others. They may not be able to imitate the movements of the therapist.[27] They deny the existence of their body part and is also known as autotopagnosia.[28]

Right and left discrimination- The patient cannot discriminate between the commands of right and left-handed tasks. This can significantly impact daily activities, as they may have difficulty following instructions that involve directional commands. Therapists use activities that involve repetitive practice of right-left discrimination, such as identifying objects placed on the right or left side and performing tasks with specific hands.

Finger agnosia- In this condition the client doesn't indicate, name, select/ differentiate the fingers of their hand[29]. It happens in patients with cerebral lesions.[30] Therapists use tactile and visual feedback exercises, where patients engage in activities that require them to touch and identify their fingers, such as finger counting games and matching tasks.

[31]In this video you will learn how to screen for finger agnosia.

Spatial Relation impairments[edit | edit source]

Figure-ground discrimination[edit | edit source]

Patients struggle to distinguish elements from the background visually[32]. This impairment can affect reading, writing, and other activities that require visual discrimination.[33] Therapists use activities that involve distinguishing objects from complex backgrounds, such as finding specific items in a cluttered room or sorting objects based on visual characteristics.

Form discrimination[edit | edit source]

Inability to identify objects of similar shapes. For example, if you ask to identify two similar objects such as an orange and a ball the patient will not be able to identify/differentiate them.

Activities include matching and sorting objects of different shapes, using tactile exploration to enhance recognition, and practicing with real-life objects to improve functional skills.

Spatial Relation[edit | edit source]

The patient is not able to locate things properly and cannot understand their relationship with one another in space and with oneself. For example, he cannot set a dining table properly and doesn't place spoons, bowls, plates appropriately.

Rehabilitation focuses on spatial orientation exercises, such as arranging objects in specific patterns, navigating through obstacle courses, and using spatial language during activities.

Position in space[edit | edit source]

The patient is unable to understand spatial concepts of up-down, front-back, out-in. If he is told to kick a ball kept in front of him via his right leg, he will not know what to do.

Therapists use directional training exercises, such as obstacle courses that require following directional commands, and interactive games that involve placing objects in specific positions.

Depth and distance perception[edit | edit source]

The patient doesn't understand where to put the leg during stair climbing. He cannot judge how much water to pour into the glass and keeps pouring even after the glass gets filled.

Exercises include practicing depth perception tasks, such as reaching for objects at different distances, using tools to measure depth, and visual feedback activities to enhance spatial judgment.

Topographical disorientation[edit | edit source]

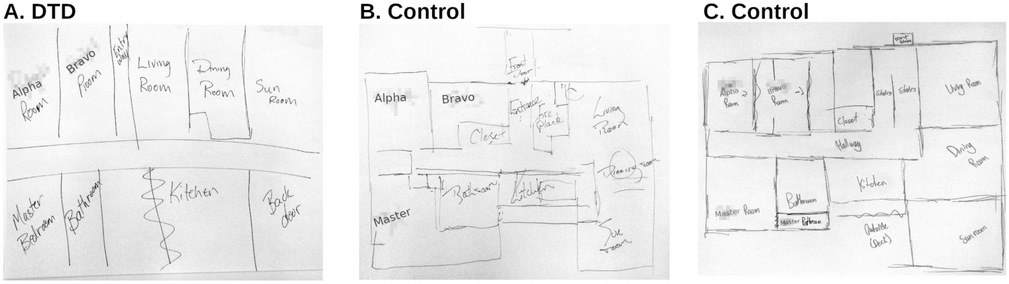

The patient has difficulty commuting from one location to the other and doesn't understand the relationship of one location to the other[34]. For example, the patient cannot find his bedroom in the house[35]. This condition is linked to lesions in the right retrosplenial cortex.

Therapists use wayfinding exercises, such as guided tours through familiar environments, map-reading tasks, and practicing navigation in controlled settings to improve spatial orientation.

Vertical disorientation[edit | edit source]

Anything vertical appears tilted to the patient. There is a lesion in the nondominant parietal lobe. If he is given the task of holding a cane, he will not hold it in a straight position, it will be tilted.[27]

Therapists use alignment tasks, where patients practice aligning objects vertically, and visual feedback techniques to correct perceptions of tilt.

Rehabilitation

Virtual reality training programs are applied on the patients with spatial relation impairments and studies have shown that it enhances the spatial cognition and it is as effective as real world training.[36]

Agnosia[edit | edit source]

In agnosia, there is the failure of recognition. Commonly seen in neurodegenerative diseases.[37]

Tactile agnosia[edit | edit source]

The tactile perceptions are intact but the patient cannot recognize the objects via palpation[38]. There is a parietal lobe lesion (unilateral/bilateral)[39]. The somatosensory functions, intellectual ability, linguistic capacity, and attention are appropriate. Rehabilitation- Faber's approach of manipulation is used in tactile agnosia[40]. This involves systematic handling of objects to enhance recognition through touch, combined with visual feedback to reinforce learning.

The following video shows different methods to identify tactile agnosia.

Auditory agnosia[edit | edit source]

The term auditory agnosia refers to disorders in the processing of auditory input due to central nervous system damage, which are not attributable to peripheral hearing loss[42]. In severe cases, these disorders lead to cortical deafness, where the patient does not respond to auditory stimuli or does so inconsistently and often inappropriately[42]. Such patients have intact language and cognitive function.[43] Rehabilitation- Lip reading and communication technique is applied in clients with auditory agnosia[44].

The following video shows a case of auditory agnosia:

Visual object agnosia[edit | edit source]

The patient cannot name the objects/faces/words presented in front of him. For example, the patient may call the bicycle , a pie. It can be assessed by copying /drawing of figures.[46]

Rehabilitation- Compensatory strategies and restorative training is applied in visual object agnosia[47]. Compensatory strategies include teaching patients to use context clues and descriptive language to identify objects. Restorative training involves repetitive practice with object naming and recognition tasks.

Rehabilitation- Compensatory strategies and restorative training is applied in visual object agnosia[48]. Compensatory strategies include teaching patients to use context clues and descriptive language to identify objects. Restorative training involves repetitive practice with object naming and recognition tasks.

Apraxia[edit | edit source]

Apraxia is a disorder in which the patient cannot perform skilled actions.[37]It is most associated with left hemisphere strokes[49].

Ideomotor apraxia[edit | edit source]

Loss of ability to imitate hand gestures[50]. The client understands the requirements but cannot execute appropriate movements. There occur errors in gesture production.

Therapists use imitation exercises, where patients replicate hand gestures and movements, combined with motor imagery techniques to improve execution of gestures. Virtual reality therapy can also be used[51].

The following video shows an example of ideomotor apraxia:

Ideational apraxia[edit | edit source]

Patients have difficulty understanding the concept of a task, leading to problems with sequencing and using objects correctly[53]. Rehabilitation involves breaking tasks into components and using visual and auditory feedback.

Rehabilitation- The tasks are broken down into various components. Each component is taught at once and practiced. Visual and auditory feedback is proved to be effective. Once the individual tests are learned properly, the physiotherapist adds the complex movement pattern steadily.[10]

Cognitive deficits[edit | edit source]

Attention Deficit Disorders[edit | edit source]

Attention Deficit Disorders are commonly seen after stroke.[54] They are common among the ones who have right brain damage. [55]The attention system has a connection with various cognitive functions like cognition, activity performance, language, memory, and spatial organization. Hence, attention deficits can highly affect the functional abilities of the person at home or work.[54]

After the cerebrovascular accident, focused attention(selective) deficit gets cured in the majority of the patients but higher-order attentional problems may persist later. This includes speed of processing, divided attention, working memory, and vigilance.[56]

Neuropsychological assessment is used to classify patients with cognitive issues like language, attention, and memory.[57]

Selective attention[edit | edit source]

Also known as focused attention. The capacity to do the task in presence of visual, auditory, or environmental stimuli.[27]It is needed when the patient has to ignore certain stimuli.

For example, The patient stops the activity of dressing while talking to the therapist/bystander. Here, the focused attention is affected.

Therapists use distraction-free environments for initial practice, gradually introducing distractions to improve focused attention. Techniques include attention control exercises and mindfulness training[58].

Sustained attention[edit | edit source]

The capacity to address relevant information during the activity. The patient can respond effectively during the task.[27]

Divided attention[edit | edit source]

The patient can respond to two or more tasks at a time.

Patients practice dual-task exercises, such as walking while counting, to improve divided attention. Gradual increases in task complexity help enhance multitasking abilities.

Alternating attention[edit | edit source]

The capacity to do multiple tasks appropriately.[27]

Rehabilitation -In attention disorders patients, simple tasks are started initially and practiced several times. Slowly the complexity is added by the therapist.

Memory[edit | edit source]

Memory decline is common after stroke and affects the functional ability of the person[59]. It occurs in approximately half the patients[60]. There are various memory deficits like long-term memory loss, short-term memory loss, and immediate recall. The overall deterioration of memory is referred to as dementia.

Rehabilitation- Memory rehabilitation which is a part of cognitive rehabilitation plays an important role in such patients. Here the use of internal and external aids can be done. Internal aids consist of mental imagery, pneumonic, and rehearsal. External aids consist of notice boards, diaries, lists to help them recall and restore the memory.[61]

Vestibular stimulation is proved to be effective to improve visual memory recall. Galvanic vestibular stimulation of low level delivers the current transcutaneously to the vestibular nerves. Here the electrodes are placed over the mastoid bones. The current is bipolar (opposite current applied over each electrode). GVS is of low cost, easy to apply and the patient need not get involved actively.[62]

Vestibular stimulation is the most common form of stimulation used in various neurological conditions and it is proved to be effective in improving motor skills.[63]

General PT rehabilitation of perceptual disorders[edit | edit source]

Clients with perceptual disorders are usually treated by occupational therapists.

Mainly there are two approaches used - The remedial approach and the Compensatory approach.

Remedial approach[edit | edit source]

As per this approach, the adult brain can repair itself after the brain injury using sensorimotor, cognitive, and perceptual exercises. During rehabilitation, the focus of the therapist is on the client's deficits. The functional abilities of the patient are improved by retraining particular perceptual components. Environmental stimuli are used during the rehabilitation.

Compensatory approach[edit | edit source]

Intact skills are utilized and compensated for the skills which are impaired. Specific training of Activities Of Daily Living is provided as it is difficult for the injured brain to learn generalized tasks.[7]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bayne T, Brainhard D, Byrne RW, Chittka L, Clayton N, Heyes C, Mather J, Ölveczky B, Shadlen M, Suddendorf T, Webb B. What is Cognition? Current Biology. 2019; 29(13): R608-R615

- ↑ Lacreuse A, Raz N, Schmidtke D, Hopkins WD, Herdon JG. Age-related decline in executive function as a hallmark of cognitive ageing in primates: an overview of cognitive and neurobiological studies. Biological Sciences. 2020; 375: 20190618

- ↑ Skidmore E, Eskes G, Brodtmann A. Executive function post-stroke: concepts, recovery, and interventions. Stroke. 2023; 54: 20-29

- ↑ Marulis LM, Nelson LJ. Metacognitive processes and associations to executive function and motivation during problem-solving task in 3-5 year olds. Metacognition and Learning. 2021; 16: 207-231

- ↑ Foley HJ. Sensation and Perception (6th edition). Routledge. 2019.

- ↑ Armstrong DM. Bodily Sensations. Taylor & Francis. 2023

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 6th edition,Philadelphia, F.A. Davis Co, O'Sullivan ,SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk G,2019 Jan 2015,Chapter 27,Cognitive and perceptual dysfunction, Physical rehabilitation.

- ↑ Esposito E, Shekhtman G, Chen P. Prevalence of spatial neglect post-stroke: A systematic review. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2021; 64(5): 101459

- ↑ Zigiotto L, Damora A, Albini F, Casati C, Scrocco G, Mancusi M, Tesio L, Vallar G, Bolognini N. Multisensory stimulation for the rehabilitation of unilateral spatial neglect. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2021; 31(9): 1410-1443

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Surya N, Someshwar H. Rehabilitation in Perceptual disorders in stroke patients. SVDA Neurology.2020 June 8th.Volume 1.

- ↑ Salatino A, Zavattaro C, Gammeri R, Cirillo E, Piatti ML, Pyasik M, Serra H, Pia L, Geminiani G, Ricci R. Virtual reality rehabilitation for unilateral spatial neglect: A systematic review of immersive, semi-immersive and non-immersive techniques. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2023; 152: 105248

- ↑ Gammeri R, Schintu S, Salatino A, Vigna F, Mazza A, Gindri P, Barba S, Ricci R. Effects of prism adaptation and visual scanning training on perceptual and response bias in unilateral spatial neglect. Neuropsychology & Rehabilitation. 2023; 34(2): 1-26

- ↑ Umeonwuka C, Roos R, Ntsiea V. Current trends in the treatment of patients with post-stroke unilateral spatial neglect: a scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2022; 44(11): 2158-2185

- ↑ Choi H-S, Lee B-M. A Complex Intervention Integration Prism Adaptation and Nek Vibration for Unilateral Neglect in Patients of Chronic Stroke: A Randomised Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(2): 13479

- ↑ Bazan R, Fonseca BH de S, Miranda JM de A, Nunes HR de C, Bazan SGZ, Luvizutto GJ. Effect of Robot-Assisted Training on Unilateral Spatial Neglect After Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2022; 36(8): 545-556

- ↑ Yong AT, Sung KJ. Comparing the effectiveness of bimanual and unimanual mirror therapy in unilateral neglect after stroke: A pilot study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2022; 50(1): 133-141

- ↑ Med-Bay. Hemineglect syndrome - Hemispatial neglect. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKC_X62D7pI [last accessed 28-06-2024]

- ↑ Robert Teasell MD, Danielle Rice BA. Perceptual Disorders.

- ↑ Steward KA, Kretzmer T. Anosognosia in moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury: A review of prevalence, clinical correlates, and diversity considerations. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2022; 36(8): 2021-2040

- ↑ Heilman KM. Anosognosia: possible neuropsychological mechanisms. Awareness of deficit after brain injury: Clinical and theoretical issues. 1991 Jan 24:53-62.

- ↑ Cutting J. Study of anosognosia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1978 Jun 1;41(6):548-55.

- ↑ Bisiach E, Vallar G, Perani D, Papagno C, Berti A. Unawareness of disease following lesions of the right hemisphere: anosognosia for hemiplegia and anosognosia for hemianopia. Neuropsychologia. 1986 Jan 1;24(4):471-82.

- ↑ De Ruijter NS, Schoonbrood AMG, van Twillert B, Hoff EI. Anosognosia in dementia: A review of current assessment instruments. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2020; 12(1): e12079

- ↑ Castrillo-Sanz A, Calvo MA, Gento IR, Delgado EI, Rios RG, Herrero RR, Tola-Arribas MA. Anosognosia in Alzheimer disease: prevalence, associated factors, and influence on disease progression. Neurologia. 2016; 31(5): 296-304

- ↑ ARTexplains Science and History. Anosognosia: Disorder Blindness. When the Paralyzed Think They Walk. The Ways Your Brain Can Break. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7tgqd05L4o&t [last accessed 28-06-2024]

- ↑ Saetta G, Zindel-Geisseler O, Stauffacher F, Serra C, Vannuscorps G, Brugger P. Asomatognosia: Structured Interview and Assessment of Visuomotor Imagery. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 11: 544544

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 O'Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk G. Physical rehabilitation. FA Davis; 2019 Jan 25.

- ↑ Nathanson M, Bergman PS, Gordon GG. Denial of illness: its occurrence in one hundred consecutive cases of hemiplegia. AMA Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry. 1952 Sep 1;68(3):380-7.

- ↑ Newman SD. Does finger sense predict addition performance? Cognitive Processing. 2016; 17(2): 139-146

- ↑ Gerstmann J. Syndrome of finger agnosia, disorientation for right and left, agraphia and acalculia: local diagnostic value. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry. 1940 Aug 1;44(2):398-408.

- ↑ Alexis Snyder. Screening video - Finger Agnosia. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1Si-RLr3LE [last accessed 28-06-2024]

- ↑ Wu Z, Guo A. Bioinspired figure-ground discrimination via visual motion smoothing. PLOS Computational Biology. 2023; 19(4): e1011077

- ↑ Schnabel UH, Bossens C, Lorteije JA, Self MW, de Beeck HO, Roelfsema PR. Figure-ground perception in the awake mouse and neuronal activity elicited by figure-ground stimuli in primary visual cortex. Scientific reports. 2018 Dec 12;8(1):1-4.

- ↑ Goulter JR, Fitzpatrick LE, Crowe SF. An analysis of distinct navigational domains and topographical disorientation syndromes in ABI: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2020; 43(5): 449-468

- ↑ Burles F, Laria G. Behavioural and cognitive mechanisms of Developmental Topographical Disorientation. Scientific Reports. 2020; 10: 20932

- ↑ Kober SE, Wood G, Hofer D, Kreuzig W, Kiefer M, Neuper C. Virtual reality in neurologic rehabilitation of spatial disorientation. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2013 Dec;10(1):1-3.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Coslett HB. Apraxia, neglect, and agnosia. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2018 Jun 1;24(3):768-82.

- ↑ Sakurai Y. Tactually-related cognitive impairments: sharing of neural substrates across associative tactile agnosia, agraphestesia, and kinesthetic reading difficulty. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2023; 123: 1893-1902

- ↑ Kumral E, Çetin FE, Özdemir HN. Cognitive and Behavioral Disorders in Patients with Superior Parietal Lobule Infarts. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2023; 50(4): 542-550

- ↑ Surya N, Someshwar H. Rehabilitation in Perceptual disorders in stroke patients. SVOA Neurology. 2020; 1(1): 1-9

- ↑ Josh Bennet. Tactile agnosia. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQIddY5G0qs [last accessed 29-06-2024]

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Miceli G, Caccia A. The Auditory Agnosias: a Short Review of Neurofunctional Evidence. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2023; 23: 671-679

- ↑ Shell AR. Auditory agnosia. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2015 Jan 1;129:573-87.

- ↑ Silva G, Gonçalves R, Taveira I, Mouzinho M, Osória R, Nzwalo H. Stroke-associated cortical deafness: a systematic review of clinical and radiological characteristics. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(11): 1383

- ↑ The Lancet. Hearing but not understanding with a brainstem lesion. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jyIhT1m6iKw [last accessed 29-06-2024]

- ↑ Coslett HB. Apraxia, neglect, and agnosia. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2018 Jun 1;24(3):768-82.

- ↑ Gobbo S. The Rehabilitation of Object Agnosia and Prosopagnosia: A Systematic Review. 2022; 217 – 240.

- ↑ Gobbo S. The Rehabilitation of Object Agnosia and Prosopagnosia: A Systematic Review. 2022; 217 – 240.

- ↑ Dressing A, Martin M, Beume L-A, Kuemmerer D, Urbach H, Kaller CP, Weiller C, Rijntjes M. The correlation between apraxia and neglect in the right hemisphere: A voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping study in 138 acute stroke patients. Cortex. 2020; 132: 166-179

- ↑ Hödl AK, Hödl E, Otti DV. Ideomotor limb apraxia in Huntington's disease. Journal of Neurology. 2008; 255: 331-339

- ↑ Wookyung P, Jongwook K, MinYoung K. Efficacy of virtual reality therapy in ideomotor apraxia rehabilitation A case report. Medicine. 2021; 100(28): e26657

- ↑ Instant Neuro. Reel-Example: Ideomotor Apraxia. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EvOYeqM-6CE [last accessed 29-06-2024]

- ↑ Clark D. Strategies to Cope with Cognitive Difficulties After a Stroke (SCOPE–Apraxia) (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Manchester (United Kingdom)).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Žagavec BS, Lešnik VM, Goljar N. Training of selective attention in work-active stroke patients. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2015 Dec 1;38(4):370-2.

- ↑ Lincoln N, Majid M, Weyman N. Cognitive rehabilitation for attention deficits following stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000(4).

- ↑ Michel JA, Mateer CA. Attention rehabilitation following stroke and traumatic brain injury. Europa medicophysica. 2006 Mar;42(1):59-67.

- ↑ Nøkleby K, Boland E, Bergersen H, Schanke AK, Farner L, Wagle J, Wyller TB. Screening for cognitive deficits after stroke: a comparison of three screening tools. Clinical rehabilitation. 2008 Dec;22(12):1095-104.

- ↑ Verhaeghen P. Mindfulness as Attention Training: Meta-Analyses on the Links Between Attention Performance and Mindfulness Interventions, Long-Term Meditation Practice, and Trait Mindfulness. Mindfulness. 2021; 12: 564-581

- ↑ Lugtmeijer S, Lammers NA, de Haan EHF. Post-Stroke Working Memory Dysfunction: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Neuropsychology Review. 2021; 31: 202-219

- ↑ O'Sullivan M, Li X, Galligan D, Pendlebury S. Cognitive recovery after stroke: memory. Stroke. 2023; 54: 44-54

- ↑ das Nair R, Cogger H, Worthington E, Lincoln NB. Cognitive rehabilitation for memory deficits after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016(9).

- ↑ Wilkinson D, Nicholls S, Pattenden C, Kilduff P, Milberg W. Galvanic vestibular stimulation speeds visual memory recall. Experimental brain research. 2008 Aug 1;189(2):243-8.

- ↑ Malekpour M, Rahimzadeh S. The effective of Vestibular stimulation on Improve motor skills in children educable mental retardation with developmental coordination disorder. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2020 Aug 10;20(2):21-32.