Exercises for Lumbar Instability: Difference between revisions

Bert Lasat (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Candace Goh (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (76 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Bruno Luca|Bruno Luca]] | '''Original Editors '''- [[User:Bruno Luca|Bruno Luca]], [[User:Lucy Bussard|Lucy Bussard]] and [[User:Kurt Kimmons|Kurt Kimmons]] | ||

''' | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == Definition/Description == | ||

[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Instability#Definition.2FDescription Lumbar instability] - is a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilising system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major deformity, and no incapacitating pain.<ref name=":0">Biely S, Smith S, Silfies S, [https://www.orthopt.org/uploads/content_files/issue_20_article_28.pdf Clinical Instability of the Lumbar Spine: Diagnosis and Intervention]. Orthopaedic Practice. 2006;18(3):6.</ref> Patients with [[Lumbar Instability|lumbar instability]] show loss of spinal motion segment stiffness in with normal external loads may cause pain, spinal deformity or damage to the neurological structures. <ref name="p9">Davarian S. et al.; Trunk muscles strength and endurance in chronic low back pain patients with and without clinical instability; Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation; 2012 (Level of evidence 1B)</ref> | |||

Stabilisation exercises have been used successfully to treat patients with segmental instability and [[Chronic Pain|chronic pain.]]<ref name=":0" /><ref>Niederer D, Engel T, Vogt L, Arampatzis A, Banzer W, Beck H, Moreno Catalá M, Brenner-Fliesser M, Güthoff C, Haag T, Hönning A, Pfeifer AC, Platen P, Schiltenwolf M, Schneider C, Trompeter K, Wippert PM, Mayer F. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32971921/ Motor Control Stabilisation Exercise for Patients with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Prospective Meta-Analysis with Multilevel Meta-Regressions on Intervention Effects]. J Clin Med. 2020 Sep 22;9(9):3058.</ref><ref>Owen PJ, Miller CT, Mundell NL, Verswijveren SJJM, Tagliaferri SD, Brisby H, Bowe SJ, Belavy DL. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31666220/ Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain?] Network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Nov;54(21):1279-1287.</ref> Evidence suggests that the lack of muscle strength can itself contribute to low back pain even in the absence of degeneration.<ref>Studnicka K, Ampat G. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562179/ Lumbar Stabilization]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2020.</ref> | |||

== | Therapy for lumbar instability must address not only the lumbar region but also the surrounding anatomical structures such as the muscles of the abdomen and lower extremities. The kind of exercises depends on the status of the patient.<ref name="p1">C. M. Norris; Back stability: integrating science and therapy; p. 63, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134,135, 140,146,149,158-161,168-171, 173,175,177,180, 181, 185, 190, 194, 196, 197, 200,205, 207, 210, 211, 215,236,242,243; 2008 (Level of evidence 5)</ref><ref name="p2">Celestini M, Marchese A, Serenelli A, Graziani G. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of physical exercise in patients braced for instability of the lumbar spine. Eura Medicophys. 2005;41: 223-231. (level of evidence 1B)</ref> Not all patients show a loss of the [[Lumbar Motor Control Training|feedforward mechanism]] but in those where the mechanism is not working well, the patients will have more pain. <ref name="p9" /> | ||

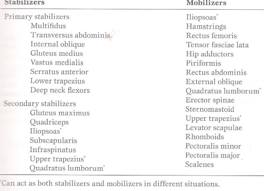

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

[https://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Instability#Clinically_Relevant_Anatomy Clinically Relevant Anatomy] of the lumbar instability. | |||

[[Image:Phy1.jpg|frame|Stabilizing and mobilizing muscles that affect the low back|none]] | |||

== Indications for Exercises == | |||

The | There are different reasons why we might give stabilisation exercises to patients with lumbar instability. The most important considerations are our treatment goals and the likelihood of a positive response to treatment. An important study by [[CPR for Lumbar Stabilisation|Hicks et al]] shows that during the [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Instability#Examination examination of lumbar instability] positive and negative determinants can be found indicating whether a subject will benefit from a low back stabilisation program.<ref name="p3">Hicks GE., Fritz JM., Delitto A., McGill SM. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program, Arch Phys Med Rehabilitation 2005; 86; 1753-1762 (level of evidence 1B)</ref><br>There are indications that [[The Effectiveness of Core Stability Exercise in the Management of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain|stabiliasation exercise]] programs are used to improve the strength, endurance and/or motor control of the abdominal and lumbar trunk musculature. Stabilisation exercise programs exist of general exercises, educational and workplace-specific back school classes, increase of workload tolerance, psychological interventions and segmental stabilisation exercises. The stabilising exercises focus on the re-education of a precise co-contraction pattern of local muscles of the spine.<ref name="p4">Rackwitz et al.; Practicability of segmental stabilizing exercises in the context of a group program for the secondary prevention of low back pain. An explorative pilot study; eura medicophys; 2007 (Level of evidence 3B)</ref><br>It had been shown that stabilising exercises along with routine exercises help with the reduction of pain intensity while increasing functional ability and muscle endurance<ref>Gomes-Neto M, Lopes JM, Conceição CS, Araujo A, Brasileiro A et al. Stabilization exercise compared to general exercises or manual therapy for the management of low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2017; 23:136-142 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.08.004</ref>. [[The Effectiveness of Core Stability Exercise in the Management of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain|Stabilising exercises]] are therefore recommended in the treatment of patients with lumbar segmental instability.<ref name="p5">Javadian Y et al.; The effects of stabilizing exercises on pain and disability of patients with lumbar segmental instability; J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil.; 2012 (Level of evidence1B)</ref> | ||

<br>Some considerations when training the local muscle system <ref>Searle A, Spink M, Ho A, Chuter V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2015;29(12):1155-1167</ref>: | |||

* Develop the skill of an independent contraction of the local muscle synergy | |||

* Decrease the contribution of the overactive global muscles | |||

* Use a motor relearning approach to reteach the skill of developing a “corset” action of transversus abdominis and multifidus in response to the cue to draw in the abdominal wall | |||

* Use specific facilitation and feedback techniques to ensure each segment of the multifidus muscle is activated | |||

* Use specific feedback techniques to develop kinaesthetic awareness of local muscle contractions | |||

* Develop ability to hold the “corset” action tonically over extended periods of time | |||

* Use repeated movements of lumbopelvic region, in non-weightbearing positions initially, to improve position sense.<ref name="p6">C. Richardson et al.; Therapeutic exercise for lumbopelvic stabilization: A motor control approach for the treatment and prevention of low back pain; p. 177-178, 180-181, 186; Churchill Livingstone; 2004 (Level of evidence5)</ref> | |||

<br>Implications for practice of the local muscle system with the global muscle system | |||

* Training the local and weightbearing muscles is likely to reverse impairments in the non-weightbearing muscles | |||

* Initially use specific facilitation techniques for the dysfunctional weightbearing muscles, with emphasis on increasing weightbearing load cues | |||

* Use optimal weightbearing postures to re-establish recruitement of both the local and weightbearing muscles | |||

* Weightbearing muscles should be trained under the stretch from gravity in flexed and more upright postures | |||

* Use static weightbearing postures with increasing holds and/or very slow and controlled weightbearing exercise to enhance the feedback mechanisms | |||

* Increase gravitational load cues gradually, ensuring local and weightbearing muscles are responding to the increases in load | |||

* At a later stage it may be necessary to add in specific muscle-lengthening techniques for non-weightbearing muscles, especially if the muscle tightness is in the passive rather than the active elements of the muscle.<ref name="p6" /> | |||

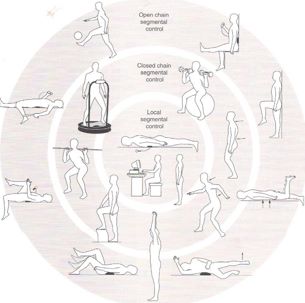

[[Image:Phy2.jpg|thumb|500px|The segmental stabilisation model for the prevention and treatment of low back pain]] | |||

The | The three stages of the exercise model form the building blocks for the development of the joint protection mechanisms, for both low- and high-load functional situations. Each stage includes clinical assessments of the level of impairment in the joint protection mechanisms, followed by the suggested exercise techniques.<ref name="p6" /> | ||

== Exercise Techniques == | |||

Optimal spinal stabilization can be achieved by [[Strength Training versus Power Training|strengthening]] the deep back and abdominal muscles. These include the [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominus]], [[Quadratus Lumborum|quadratus lumborum]], oblique abdominals, [[Lumbar Multifidus|multifidus]] and [[Erector Spinae|erector spinae]]. Exercises targeting these specific muscles should be done in a progression, usually beginning with [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominus]] which provides the patient with initial stabilisation that is helpful during subsequent exercises and daily activities. | |||

=== Motor control exercises === | |||

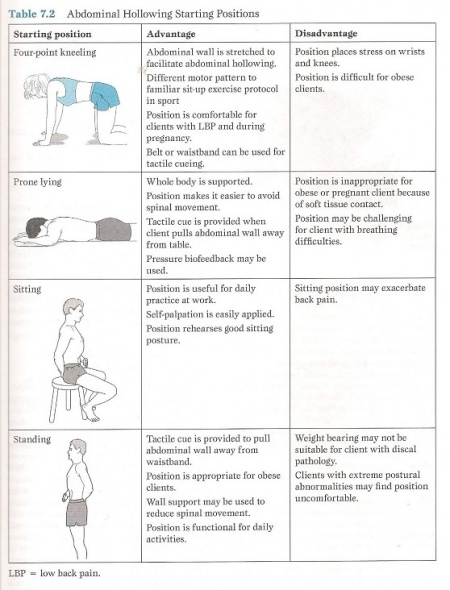

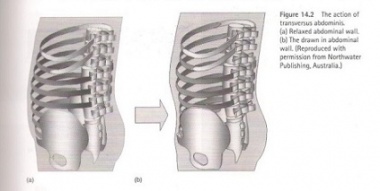

==== '''''Contraction of transversus abdominus''''' ==== | |||

Without contraction of the overlying abdominals. Normally [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominus]] should be in a state of continual contraction whether in standing and sitting, facilitating good posture. In patients with low back pain, [[Transversus Abdominis|Transversus abdominus]] can become deactivated, leading to an unstable core but additional global musculature may also be co-contracted in an effort to regain some control. | |||

The | The goal of this exercise is that patients with low back pain learn to contract [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominus]] at all times (except when lying). After a time the muscle should return to its natural state of continuous contraction. It is very important for patients with [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]] to have good posture which will be assisted by retraining [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominus]]. <ref name="p2" /> | ||

Technique: The patient pulls his belly in and up at the navel without moving the rib cage, pelvis or spine. Contraction intensity: 30 to 40% of the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). Progression: Gradually build up the duration of the contraction. Only when the patient can activate [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominus]] with minimal muscle intensity (10 repetitions each 30-40%) over a period of time, should more advanced exercises be added. <ref name="p1" /><br><br> | |||

{| width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" | |||

|- | |||

| [[Image:Phy5.jpg|thumb|left|450px]] | |||

| [[Image:Phy6.jpg|thumb|left|380px|a) Relaxed Abdominal Wall b) The Drawn-in Abdominal Wall]] | |||

<ref name="p4" /> | |||

|} | |||

==== '''''Contraction of the multifidus''''' ==== | |||

This muscle is the most important stabilizer of the spinal extensor group. People with low back pain often lose the ability to contract this muscle and they do not regain the ability spontaneously. Technique: First the patient learns to recognize what is feels like to tense and relax the muscle then also how to include the lateral abdominals in the contraction. <ref name="p9" /> | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

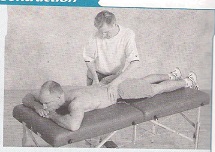

| Prone lying [[Lumbar Multifidus|multifidus]] contraction<br> [[Image:Phy10.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Teach clients to learn to use the multifidus at will and seperately from other muscles.<br>The multifidus is the most important stabilizer of the spinal extensor group. People with low back pain often lose the ability to contract this muscle and do not regain the ability spontaneously. <br>Prone-lying position<br>Therapist palpates the multifidus.<br>Bulge the muscles beneath the fingers of the therapist and differentiate between erector spinae contraction(more lateral) and multifidus contraction(more central).<br>To differentiate between the multifidus muscle and the erector spinae muscle, it’s recommended to contract the erector spinae muscle by hyperextend the trunk. To contract only the multifidus muscle, the patient may not hyperextend the trunk.<ref name="p1" /><br>A movie of this exercise is shown in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Spinal_Stabilization#Description spinal stabilization].<br> | |||

|- | |||

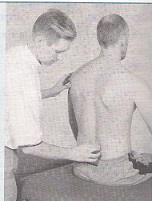

| Sitting [[Lumbar Multifidus|multifidus]] contraction<br> [[Image:Phy11.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Encourage your client to contract the multifidus and lateral abdominals simultaneously.<br>Client sit on the edge of a bench with his feet on the floor.<br>Lumbar spine in neutral position.<br>Therapist palpates the multifidus.<br>Client performs abdominal hollowing<br>If the therapist feels the contraction, the client can self-palpate and continue the action for 10 repetitions, aiming to hold each for 10 s while breathing normally. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

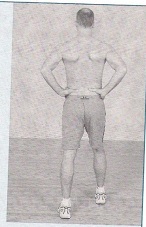

| Forward stride(walk) standing [[Lumbar Multifidus|multifidus]] contraction<br> [[Image:Phy12.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Encourage your client to contract the multifidus and lateral abdominals simultaneously.<br>Stand with one foot in front of the other<br>Self-palpate the L4-L5 level by placing the thumbs on the lower lumbar spinous process and moving them outward slightly into the spinal tissue.<br>Place the weight onto the front leg and then onto the back leg alternately.<br>Feel the muscles beneath the thumbs switching on and off. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|} | |||

{| class="FCK__ShowTableBorders" width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" align="center" | |||

|- | |||

| | |||

{{#ev:youtube|aqwx6uCwhUQ|300}} | |||

| {{#ev:youtube|fUU0pGZ0v_U|300}} | |||

|- | |||

| <ref>online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqwx6uCwhUQ, last accessed 6/2/09</ref><br> | |||

| <ref>online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fkt1TOn1UfI, last accessed 6/2/09</ref><br> | |||

|} | |||

==== '''''Control of the pelvic muscles''''' ==== | |||

This is important to move confidently into a neutral lumbar position. People with low back pain do not have the ability to perform [[Pelvic Tilt|pelvic tilting]]. You can see excessive flexion laxity but limited or blocked extension. The ability to dissociate lumbar movement from pelvic movement is therefore important and correction of faulty lumbar-pelvic rhythm is vital. <ref name="p9" /> | |||

==== '''''Diaphragm''''' ==== | |||

The activity of the diaphragm is also reduced in association with rapid limb movement and support surface translation while global muscle activity is increased. People with respiratory disease are predicted to have increased incidence of low back pain. <ref name="p8">Lamounier Sakamoto AC, et al,. Muscular activation patterns during active prone hip extension exercises. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2009;19:105–112. (level of evidence 2B)</ref> | |||

==== '''Spine-control exercises''' ==== | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

| | |||

Prone kneeling [[Lumbopelvic Rhythm|Lumbar-Pelvic Rhythm]] | |||

[[Image:Phy7.jpg|center]] | |||

< | <ref name="p1" /> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Goal: Facilitate active pelvic tilt.<br>Prone kneeling with shoulders directly above the hands and hip above the knees<br>Phase 1(a): no lumbar or pelvic movement should occur<br>Phase 2(b):posterior pelvic tilt and hip flexion occur<br>Phase 3(c) :Lumbar flexion and some thoracic flexion finish the action<br>(d): Faulty lumbar-pelvic rhythm often shows up when lumbar flexion and posterior pelvic tilt occur immediately.<br>Building:<br>1) The patient learns the tilting<br>2) The tilting has to be rhythmic <ref name="p1" /><br>The control of the pelvic muscles is important to move confidently into a neutral lumbar position. People with low back pain don’t have the ability to perform pelvic tilting. They exhibit also a limited excessive flexion laxity or blocked extension. <ref name="p5" /><br>The ability to dissociate lumbar movement from pelvic movement is therefore important and the correction of faulty lumbar-pelvic rhythm is vital. <ref name="p5" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| High(two-point) kneeling (assisted) hip hinge action<br> [[Image:Phy8.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Use a pelvic tilt action to move the spine forward and backward.<br>Once you can perform pelvic tilting well, you should combine it with classic hip in a hinge action where the trunk moves on the hip in a hinge action and the spine remains straight.<br>Avoid any increase or decrease in lumbar lordosis!<br>Draw the abdominal muscles and maintain this minimal contraction throughout the movement! <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Sitting pelvic tilt using gym ball<br> [[Image:Phy9.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Teach anterior-posterior pelvic tilt control.<br>Sit on the ball with knees apart and feet flat on the floor. Both hips and knees should be flexed to about 90°.<br>Tilt pelvis alternately in both anterior and posterior directions, making sure the shoulders and thoracic spine remain inactive.<br>Start with small ranges of movement.<br>Gradually work up to larger ranges. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|} | |||

=== Core training === | |||

==== '''Primary exersice''' ==== | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

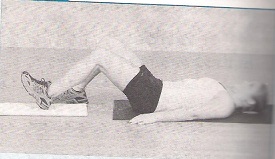

| Heel Slide – Basic Movement<br> [[Image:Phy13.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Place minimal but progressive limb loading on the trunk.<br>Slowly straighten one leg with the heel resting on the ground. The moment the pelvis anteriorly tilts and the lordosis increases, you must stop the movement and draw the leg back into flexion. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

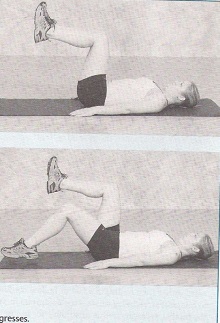

| Leg Lowering<br> [[Image:Phy14.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| This exercise is described in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Core_stability#Physical_therapy_management core stability]. <br>‘Leg extensions’<br> | |||

|- | |||

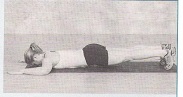

| Prone-Lying Gluteal Brace<br> [[Image:Phy15.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: co-contract trunk stabilizers with gluteals.<br>Patient has to lie down and dorsiflex the toes. Flex than the knees ( 10°) and the hip (10°). After that contract the gluteal muscles. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Bridge from Crook Lying (Shoulder Bridge)<br> [[Image:Phy16.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| This exercise is described in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Core_stability#Physical_therapy_management core stability].<br>‘Dynamic leg and back’<br> | |||

|- | |||

| Bridge with leg lift<br> [[Image:Phy17.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: progress from bridge from crook lying. <br>The patient starts in crook lying ,then he lifts one leg. <br>Avoid : allow the pelvis to fall toward the unsupported side! <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Four-point Kneeling Leg movement<br> [[Image:Phy18.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| This exercise is described in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Core_stability#Physical_therapy_management core stability]. <br>‘Hamstrings raising’.<br> | |||

|- | |||

| Four- point Kneeling arm and leg lift (full bridge)<br> [[Image:Phy19.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| A movie of this exercise is shown in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Lumbar_Spine_Fracture#Physical_Therapy_Management_.28current_best_evidence.29 lumbar spine fracture].<br>‘Bird dog’<br> | |||

|- | |||

| Side-Lying spine lengthening<br> [[Image:Phy20.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: control the quadratus lumborum and lateral fibers of the oblique abdominals.<br>Start position: strong co-contraction of the abdominal muscles. Lie on one side, thighs in line with your body and flex the knees 90°. Upper body supported on the same side elbow. Straighten your spine against the force of gravity, leaving the body supported on the forearm of the underneath arm and hip. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Side-lying hip lift<br> [[Image:Phy21.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| A movie of this exercise is shown in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain_and_Pelvic_Floor_Disorders#Physical_Therapy_Management low back pain and pelvic floor disorders].<br>‘Oblique abdominals’<br> | |||

|- | |||

| Side-lying body lift(Side bridge)<br> [[Image:Phy22.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: progress from side-lying spine lengthening.<br>Start position: side-lying spine lengthening. Lift the hips, leaving the body supported on the forearm of the underneath arm and the knees only. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Pelvic shift with leg lift<br> [[Image:Phy23.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: teach pelvic control and stability in single-leg standing.<br>Shift the pelvis to the left, lift slowly the right leg.<br>The supporting leg supports the pelvis and the pelvis supports the back. Raise the knee no more than 45°.<ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Sitting knee raise<br> [[Image:Phy24.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: maintain pelvic positon against the pull of the hip flexors. <br>Raise one knee, about 8 cm. Unload the limb by lifting the heel. If he is able to maintain good alignment, have him lift the entire leg. <br>Avoid: posterior pelvic tilt! <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|} | |||

<br> | |||

The following videos are examples demonstrating progressions of spinal stabilization exercises that can be used for patients requiring this technique. They can and should be modified according to specific patient needs, preferences, or functional demands. The physical therapist should remember to consistently stress the importance of maintaining a neutral spine when performing these exercises. | |||

<br> | |||

== | {| class="FCK__ShowTableBorders" width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" align="center" | ||

|- | |||

| | |||

{{#ev:youtube|zJ63XJQbp7k|300}} | |||

| {{#ev:youtube|bsJ7smHAyJk|300}} | |||

|- | |||

| <ref>online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJ63XJQbp7k, last accessed 6/2/09</ref><br> | |||

| <ref>online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsJ7smHAyJk, last accessed 6/2/09</ref><br> | |||

|} | |||

==== '''Variations with ball''' ==== | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

| Sitting knee raise on gym ball<br>[[Image:Phy29.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| This exercise is described in [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Low_Back_Pain_and_Pregnancy#Exercises: low back pain and pregancy]. | |||

|- | |||

| Lying trunk curl with leg lift<br>[[Image:Phy30.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: strengthen upper and lower abdominals. <br>Start position: lying trunk curl over ball. The patient should lift one leg while maintaining the stable position. <br>! lying over the ball is a good way to stretch the whole spine! <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

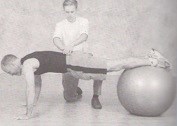

| Bridge with therapist pressure<br>[[Image:Phy31.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Strengthen hip and trunk stability muscles by challenging stability with continuously variable overload from multiple directions.<br>Start position: the standard bridge, his feets on a ball. The therapist pushes the patient against his pelvis from above and below and side to side.<br>Rapid pushes will decrease muscle reaction time, training the muscles to contract more quickly without loss of intensity. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

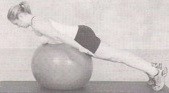

| Basic superman<br>[[Image:Phy32.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: strengthen the spinal and hip extensors. <br>The patient has to lie down with her abdomen on the ball and her feets astride and flat against a wall. Tight the abdominal muscles to form a firm surface pressing against the ball and retract the head. The patient retracts and depresses her shoulders to draw the arms downward and back and extend the thoracic spine to bring the chest off the bal. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|- | |||

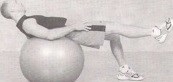

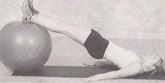

| Reverse bridge<br>[[Image:Phy33.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Strengthen back and hip muscles while increasing leg motion control. <br>Start position: high position of the reverse bridge movement. The patient has to roll the ball toward herself by flexing her knees and hips and roll it away by extending her legs again. <ref name="p1" /> | |||

|- | |||

| Wall sit<br>[[Image:Phy34.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: Prepare the body for lifting while strengthening the legs to provide power for the lift. <br>Start position: ball between back and wall.<br>1) Sitting position while rolling the ball down the wall. When he achieves 90° hip and knee flexion, the patient needs to hold the position. <br>2) Single-leg wall sit, straightening on leg at the knee. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|} | |||

<br> | |||

==== '''Exersice with unstable Base''' ==== | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" | |||

|- | |||

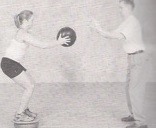

| Throwing and catching on a mobile surface<br>[[Image:Phy26.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: develop rapid-onset back stability.<br>Throwing and catching a bal on a mobil surface while you try to stabilize it.The aim is to align the lumbar spine optimally. <ref name="p1" /><br><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Sitting pelvic tilt, progressing to balance board<br>[[Image:Phy27.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: advanced control of pelvic tilt. <br>The patient needs to sit down on a wooden bench with the feets on the floor. Than hold the pelvis alternately in the anterior and then posterior direction. The aim is to isolate the pelvis and lower lumbar spine from the thoracic spine and the shoulders from the upper lumbar spine.<br>Maintain the position of the shoulders and thoracic spine. <ref name="p1" /><br><br> | |||

|- | |||

| Neutral position maintenance<br>[[Image:Phy28.jpg]]<ref name="p1" /> | |||

| Goal: build stability reaction speed in sitting.<br>The patient has to try to balance his body while a person knock the patient. The patient sits in a neutral position on a wobble board. Work gradually up the pressure. <ref name="p1" /><br> | |||

|} | |||

=== Lower extremity muscle exercises === | |||

It is possible that lumbar instability is not only limited to the lumbar spine and its associated anatomical structures. For instance, [[Sacroiliac Joint|sacro-iliac joint]] instability also plays a part and can be the cause of low back pain. Studies have found that a big contributor to this sacro-iliac joint instability and low back pain is the malrecruitment of [[Gluteus Maximus|gluteus maximus]] and [[Biceps Femoris|biceps femoris]].<ref name="p7">http://www.ibodz.com/exercise/gluteal-stretch. Consulted on 30-11-2013 (Level of evidence 5)</ref>,<ref name="p8" /><br> | |||

[[Image:Phy37.png|center]] | |||

<br> | |||

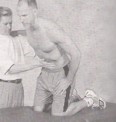

The patient has to perform a few slow hip extensions. The physiotherapist places one hand on gluteus maximus of the patient and one on the hamstrings for feedback. If done correctly, the therapist will feel the hand on gluteus maximus being pushed away before the hamstrings are activated. | |||

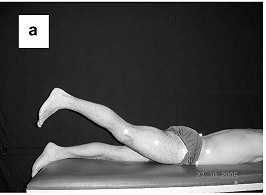

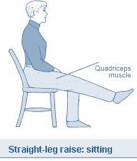

== | <br>It has been shown that there is a relationship, especially in muscle coordination, between the muscles that stabilize the lumbar spine and the muscles in the lower extremity. These muscles therefore should be trained as well in order to further achieve a balanced and coordinated muscular system.<ref name="p8" />The quadriceps also play a part in this relationship. A study has found that patients with low back pain have deteriorating function of the [[Quadriceps Muscle|quadriceps]], with reduced endurance and feedforward compared to normal. The study found that this is due to reduced quadriceps activation after localized lumbar paraspinal fatiguing isometric exercise. Exercises aimed at localized fatigue of the lumbar spine extensors have shown an immediate response in the lower extremity including reduced quadriceps central activation ratio deteriorated balance and response to a balance perturbation. Furthermore they describe a quadriceps fatigability during maximal effort isokinetic knee extension contractions.<ref name="p0">http://protherapysupplies.blogspot.be/2010/11/pro-therapy-supplies-carries.html (Level of evidence 5)</ref> The two main functions of the quadriceps are extension of the knee and flexion of the hip.<br> | ||

[[Image:Phy38.jpg|center]]<ref name="p8" /> | |||

<br> | |||

The patient starts with both his feet on the ground. The patient then straightens one leg and holds this position for about 10 seconds before switching legs. To make this exercise a loaded exercise, the patient can do this exercise with weights (for instance on a leg extension machine). Ask the patient to hold for 1-3 seconds. | |||

<br> | |||

=== Exercises for patients who are braced === | |||

It has been shown that patients who are braced with an orthosis for lumbar instability benefit from some of the exercises described above. A study found that patients who were braced and did the following exercises had a decreased level of pain.<br> | |||

*Gluteal and ischiocrural stretching exercises performed in an unloaded way. | |||

*Contraction exercises of the lumbar stabilizing muscles, in particular [[Transversus Abdominis|''transversus abdominus'']]. | |||

*Exercises for trunk stabilization on ever more reduced supporting surfaces and finally on unstable surfaces.<ref name="p2" /><br> | |||

=== Stabiliser === | |||

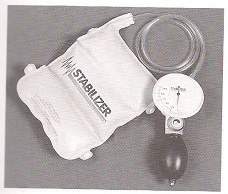

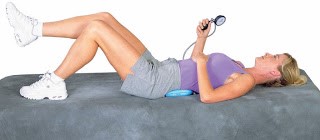

Depending on treatment findings, a patient may need to start with some basic muscle activation. A stabiliser has come into general use for stabilisation exercises for all parts of the body. A stabiliser is a pressure biofeedback unit and consists of an inelastic, three-section air-filled bag, which is inflated to fill the space between the target body area, a firm surface and a pressure dial for monitoring the pressure in the bag for feedback on position. The bag is inflated to an appropriate level for the purpose and the pressure recorded. Movement of the body part off the bag results in a decrease in pressure while movement of the body part into the bag results in an increase in pressure. Its use in assessing the abdominal drawing-in action has become its most important use in relation to the treatment of problems for the local muscle system in patients with low back pain. <ref name="p6" /> | |||

[[Image:Phy3.jpg|center]]<ref name="p6" /> | |||

The patient is position in hook-lying. The feet remain flat and the arms are held alongside the body. The stabiliser is positioned under the lumbar lordosis. During exercises the spine cannot make any movements. The [[Transversus Abdominis|transversus abdominis]] is contracted while doing the exercises to maintain an appropriate position. Below the woman is holding the feedback unit to monitor the amplitude of her spinal movement (based on the pressure change on the dial). <ref name="p0" />, <ref name="p1" /> | |||

[[Image:Phy4.jpg|center]]<sup><ref name="p0" /></sup> | |||

== Key Research == | |||

Fritz et al. examined the predictive validity of lumbar segmental mobility in patients with LBP. It is possible that patients with segmental hypermobility were more likely to achieve clinical success with stabilization exercises compared with patients without hypermobility.<ref name="p0" /> | |||

It has been showed in the research of Hides et al. that the Lumbar Multifidus muscle remained atrophied after a 10-week period when patients with acute LBP did not exercise. But this muscle was recovered to normal size in patients who received a stabilisation exercise program that stressed deep abdominal and isolated the Lumbar Multifidus muscle contractions.<ref name="p1" /> | |||

In the study of Richard A et al. some patient groups demonstrated hypertrophy of the Lumbar Multifidus muscles with low-load stabilisation exercises. There are indications that the Lumbar Multifidus muscle is inhibited in patients with LBP and the retraining of the muscle to contract may be the major importance during stabilisation training. <ref name="p2" /> | |||

There are also indications that many exercises commonly used by physical therapists in LBP rehabilitation require low to moderate muscle activity of the Lumbar Multifidus and Longissimus thoracicus muscles. To increase the activity of these muscles during exercise, active or resisted lumbar extension is required. Resisted lumbar extension at the end range tends to maximum activity of these muscles.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

It has been showed that segmental stabilisation exercise was more effective than placebo intervention in symptomatic lumbar segmental instability.<ref name="p3" /> | |||

It also has been showed that specific muscle stabilisation retraining is more relevant for patients with either gross spinal symptoms or pronounced side to side differences in the size of the multifidus muscle than for patients that have no signals of instability. <ref name="p4" /> | |||

The mode of action of stabilisation retraining still remains unclear. It has not been shown to be capable of mechanically containing an unstable segment, even upon improvement of muscle activation. No direct long-term effect of stabilisation exercises on the status of the local stabilising muscles has been demonstrated. <ref name="p4" /> | |||

The commission advises of a study that evaluated the effect of unstable and unilateral resistance exercises on trunk muscle activation revealed that, regardless of stability, the superman exercise was the most effective trunk-stabiliser exercise for back-stabiliser activation. The side bridge was the optimal exercise for lower-abdominal muscle activation. Thus, the most effective means for trunk strengthening should involve back or abdominal exercises with unstable bases. Furthermore, trunk strengthening can also occur when performing resistance exercises for the limbs, if the exercises are performed unilaterally.<ref name="p5" /> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | |||

On this page there are a lot of exercises. To be sure the patients stays motivated it’s important to take care of variation in the exercises you give. It’s possible using this page and your clinical reasoning to vary your therapy for patients with [[Low Back Pain|low back pain]]. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> <br> | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project | [[Category:Interventions]] | ||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine]] | |||

[[Category:Lumbar Spine - Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | |||

[[Category:MCG_Student_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | |||

Latest revision as of 12:01, 24 April 2024

Original Editors - Bruno Luca, Lucy Bussard and Kurt Kimmons

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Bert Lasat, Bruno Luca, Jona Van den Broeck, Denys Nahornyi, Admin, Kim Jackson, Blessed Denzel Vhudzijena, WikiSysop, Evan Thomas, Saeed Dokhnan, 127.0.0.1, Liam Butterworth and Candace Goh

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lumbar instability - is a significant decrease in the capacity of the stabilising system of the spine to maintain the intervertebral neutral zones within the physiological limits so that there is no neurological dysfunction, no major deformity, and no incapacitating pain.[1] Patients with lumbar instability show loss of spinal motion segment stiffness in with normal external loads may cause pain, spinal deformity or damage to the neurological structures. [2]

Stabilisation exercises have been used successfully to treat patients with segmental instability and chronic pain.[1][3][4] Evidence suggests that the lack of muscle strength can itself contribute to low back pain even in the absence of degeneration.[5]

Therapy for lumbar instability must address not only the lumbar region but also the surrounding anatomical structures such as the muscles of the abdomen and lower extremities. The kind of exercises depends on the status of the patient.[6][7] Not all patients show a loss of the feedforward mechanism but in those where the mechanism is not working well, the patients will have more pain. [2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy of the lumbar instability.

Indications for Exercises[edit | edit source]

There are different reasons why we might give stabilisation exercises to patients with lumbar instability. The most important considerations are our treatment goals and the likelihood of a positive response to treatment. An important study by Hicks et al shows that during the examination of lumbar instability positive and negative determinants can be found indicating whether a subject will benefit from a low back stabilisation program.[8]

There are indications that stabiliasation exercise programs are used to improve the strength, endurance and/or motor control of the abdominal and lumbar trunk musculature. Stabilisation exercise programs exist of general exercises, educational and workplace-specific back school classes, increase of workload tolerance, psychological interventions and segmental stabilisation exercises. The stabilising exercises focus on the re-education of a precise co-contraction pattern of local muscles of the spine.[9]

It had been shown that stabilising exercises along with routine exercises help with the reduction of pain intensity while increasing functional ability and muscle endurance[10]. Stabilising exercises are therefore recommended in the treatment of patients with lumbar segmental instability.[11]

Some considerations when training the local muscle system [12]:

- Develop the skill of an independent contraction of the local muscle synergy

- Decrease the contribution of the overactive global muscles

- Use a motor relearning approach to reteach the skill of developing a “corset” action of transversus abdominis and multifidus in response to the cue to draw in the abdominal wall

- Use specific facilitation and feedback techniques to ensure each segment of the multifidus muscle is activated

- Use specific feedback techniques to develop kinaesthetic awareness of local muscle contractions

- Develop ability to hold the “corset” action tonically over extended periods of time

- Use repeated movements of lumbopelvic region, in non-weightbearing positions initially, to improve position sense.[13]

Implications for practice of the local muscle system with the global muscle system

- Training the local and weightbearing muscles is likely to reverse impairments in the non-weightbearing muscles

- Initially use specific facilitation techniques for the dysfunctional weightbearing muscles, with emphasis on increasing weightbearing load cues

- Use optimal weightbearing postures to re-establish recruitement of both the local and weightbearing muscles

- Weightbearing muscles should be trained under the stretch from gravity in flexed and more upright postures

- Use static weightbearing postures with increasing holds and/or very slow and controlled weightbearing exercise to enhance the feedback mechanisms

- Increase gravitational load cues gradually, ensuring local and weightbearing muscles are responding to the increases in load

- At a later stage it may be necessary to add in specific muscle-lengthening techniques for non-weightbearing muscles, especially if the muscle tightness is in the passive rather than the active elements of the muscle.[13]

The three stages of the exercise model form the building blocks for the development of the joint protection mechanisms, for both low- and high-load functional situations. Each stage includes clinical assessments of the level of impairment in the joint protection mechanisms, followed by the suggested exercise techniques.[13]

Exercise Techniques[edit | edit source]

Optimal spinal stabilization can be achieved by strengthening the deep back and abdominal muscles. These include the transversus abdominus, quadratus lumborum, oblique abdominals, multifidus and erector spinae. Exercises targeting these specific muscles should be done in a progression, usually beginning with transversus abdominus which provides the patient with initial stabilisation that is helpful during subsequent exercises and daily activities.

Motor control exercises[edit | edit source]

Contraction of transversus abdominus[edit | edit source]

Without contraction of the overlying abdominals. Normally transversus abdominus should be in a state of continual contraction whether in standing and sitting, facilitating good posture. In patients with low back pain, Transversus abdominus can become deactivated, leading to an unstable core but additional global musculature may also be co-contracted in an effort to regain some control.

The goal of this exercise is that patients with low back pain learn to contract transversus abdominus at all times (except when lying). After a time the muscle should return to its natural state of continuous contraction. It is very important for patients with low back pain to have good posture which will be assisted by retraining transversus abdominus. [7]

Technique: The patient pulls his belly in and up at the navel without moving the rib cage, pelvis or spine. Contraction intensity: 30 to 40% of the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). Progression: Gradually build up the duration of the contraction. Only when the patient can activate transversus abdominus with minimal muscle intensity (10 repetitions each 30-40%) over a period of time, should more advanced exercises be added. [6]

Contraction of the multifidus[edit | edit source]

This muscle is the most important stabilizer of the spinal extensor group. People with low back pain often lose the ability to contract this muscle and they do not regain the ability spontaneously. Technique: First the patient learns to recognize what is feels like to tense and relax the muscle then also how to include the lateral abdominals in the contraction. [2]

Prone lying multifidus contraction [6] [6]

|

Goal: Teach clients to learn to use the multifidus at will and seperately from other muscles. The multifidus is the most important stabilizer of the spinal extensor group. People with low back pain often lose the ability to contract this muscle and do not regain the ability spontaneously. Prone-lying position Therapist palpates the multifidus. Bulge the muscles beneath the fingers of the therapist and differentiate between erector spinae contraction(more lateral) and multifidus contraction(more central). To differentiate between the multifidus muscle and the erector spinae muscle, it’s recommended to contract the erector spinae muscle by hyperextend the trunk. To contract only the multifidus muscle, the patient may not hyperextend the trunk.[6] A movie of this exercise is shown in spinal stabilization. |

Sitting multifidus contraction [6] [6]

|

Goal: Encourage your client to contract the multifidus and lateral abdominals simultaneously. Client sit on the edge of a bench with his feet on the floor. Lumbar spine in neutral position. Therapist palpates the multifidus. Client performs abdominal hollowing If the therapist feels the contraction, the client can self-palpate and continue the action for 10 repetitions, aiming to hold each for 10 s while breathing normally. [6] |

Forward stride(walk) standing multifidus contraction [6] [6]

|

Goal: Encourage your client to contract the multifidus and lateral abdominals simultaneously. Stand with one foot in front of the other Self-palpate the L4-L5 level by placing the thumbs on the lower lumbar spinous process and moving them outward slightly into the spinal tissue. Place the weight onto the front leg and then onto the back leg alternately. Feel the muscles beneath the thumbs switching on and off. [6] |

| [14] |

[15] |

Control of the pelvic muscles[edit | edit source]

This is important to move confidently into a neutral lumbar position. People with low back pain do not have the ability to perform pelvic tilting. You can see excessive flexion laxity but limited or blocked extension. The ability to dissociate lumbar movement from pelvic movement is therefore important and correction of faulty lumbar-pelvic rhythm is vital. [2]

Diaphragm[edit | edit source]

The activity of the diaphragm is also reduced in association with rapid limb movement and support surface translation while global muscle activity is increased. People with respiratory disease are predicted to have increased incidence of low back pain. [16]

Spine-control exercises[edit | edit source]

|

Prone kneeling Lumbar-Pelvic Rhythm

|

Goal: Facilitate active pelvic tilt. Prone kneeling with shoulders directly above the hands and hip above the knees Phase 1(a): no lumbar or pelvic movement should occur Phase 2(b):posterior pelvic tilt and hip flexion occur Phase 3(c) :Lumbar flexion and some thoracic flexion finish the action (d): Faulty lumbar-pelvic rhythm often shows up when lumbar flexion and posterior pelvic tilt occur immediately. Building: 1) The patient learns the tilting 2) The tilting has to be rhythmic [6] The control of the pelvic muscles is important to move confidently into a neutral lumbar position. People with low back pain don’t have the ability to perform pelvic tilting. They exhibit also a limited excessive flexion laxity or blocked extension. [11] The ability to dissociate lumbar movement from pelvic movement is therefore important and the correction of faulty lumbar-pelvic rhythm is vital. [11] |

High(two-point) kneeling (assisted) hip hinge action [6] [6]

|

Goal: Use a pelvic tilt action to move the spine forward and backward. Once you can perform pelvic tilting well, you should combine it with classic hip in a hinge action where the trunk moves on the hip in a hinge action and the spine remains straight. Avoid any increase or decrease in lumbar lordosis! Draw the abdominal muscles and maintain this minimal contraction throughout the movement! [6] |

Sitting pelvic tilt using gym ball [6] [6]

|

Goal: Teach anterior-posterior pelvic tilt control. Sit on the ball with knees apart and feet flat on the floor. Both hips and knees should be flexed to about 90°. Tilt pelvis alternately in both anterior and posterior directions, making sure the shoulders and thoracic spine remain inactive. Start with small ranges of movement. Gradually work up to larger ranges. [6] |

Core training[edit | edit source]

Primary exersice[edit | edit source]

Heel Slide – Basic Movement [6] [6]

|

Goal: Place minimal but progressive limb loading on the trunk. Slowly straighten one leg with the heel resting on the ground. The moment the pelvis anteriorly tilts and the lordosis increases, you must stop the movement and draw the leg back into flexion. [6] |

Leg Lowering [6] [6]

|

This exercise is described in core stability. ‘Leg extensions’ |

Prone-Lying Gluteal Brace [6] [6]

|

Goal: co-contract trunk stabilizers with gluteals. Patient has to lie down and dorsiflex the toes. Flex than the knees ( 10°) and the hip (10°). After that contract the gluteal muscles. [6] |

Bridge from Crook Lying (Shoulder Bridge) [6] [6]

|

This exercise is described in core stability. ‘Dynamic leg and back’ |

Bridge with leg lift [6] [6]

|

Goal: progress from bridge from crook lying. The patient starts in crook lying ,then he lifts one leg. Avoid : allow the pelvis to fall toward the unsupported side! [6] |

Four-point Kneeling Leg movement [6] [6]

|

This exercise is described in core stability. ‘Hamstrings raising’. |

Four- point Kneeling arm and leg lift (full bridge) [6] [6]

|

A movie of this exercise is shown in lumbar spine fracture. ‘Bird dog’ |

Side-Lying spine lengthening [6] [6]

|

Goal: control the quadratus lumborum and lateral fibers of the oblique abdominals. Start position: strong co-contraction of the abdominal muscles. Lie on one side, thighs in line with your body and flex the knees 90°. Upper body supported on the same side elbow. Straighten your spine against the force of gravity, leaving the body supported on the forearm of the underneath arm and hip. [6] |

Side-lying hip lift [6] [6]

|

A movie of this exercise is shown in low back pain and pelvic floor disorders. ‘Oblique abdominals’ |

Side-lying body lift(Side bridge) [6] [6]

|

Goal: progress from side-lying spine lengthening. Start position: side-lying spine lengthening. Lift the hips, leaving the body supported on the forearm of the underneath arm and the knees only. [6] |

Pelvic shift with leg lift [6] [6]

|

Goal: teach pelvic control and stability in single-leg standing. Shift the pelvis to the left, lift slowly the right leg. The supporting leg supports the pelvis and the pelvis supports the back. Raise the knee no more than 45°.[6] |

Sitting knee raise [6] [6]

|

Goal: maintain pelvic positon against the pull of the hip flexors. Raise one knee, about 8 cm. Unload the limb by lifting the heel. If he is able to maintain good alignment, have him lift the entire leg. Avoid: posterior pelvic tilt! [6] |

The following videos are examples demonstrating progressions of spinal stabilization exercises that can be used for patients requiring this technique. They can and should be modified according to specific patient needs, preferences, or functional demands. The physical therapist should remember to consistently stress the importance of maintaining a neutral spine when performing these exercises.

| [17] |

[18] |

Variations with ball[edit | edit source]

Sitting knee raise on gym ball [6] [6]

|

This exercise is described in low back pain and pregancy. |

Lying trunk curl with leg lift [6] [6]

|

Goal: strengthen upper and lower abdominals. Start position: lying trunk curl over ball. The patient should lift one leg while maintaining the stable position. ! lying over the ball is a good way to stretch the whole spine! [6] |

Bridge with therapist pressure [6] [6]

|

Goal: Strengthen hip and trunk stability muscles by challenging stability with continuously variable overload from multiple directions. Start position: the standard bridge, his feets on a ball. The therapist pushes the patient against his pelvis from above and below and side to side. Rapid pushes will decrease muscle reaction time, training the muscles to contract more quickly without loss of intensity. [6] |

Basic superman [6] [6]

|

Goal: strengthen the spinal and hip extensors. The patient has to lie down with her abdomen on the ball and her feets astride and flat against a wall. Tight the abdominal muscles to form a firm surface pressing against the ball and retract the head. The patient retracts and depresses her shoulders to draw the arms downward and back and extend the thoracic spine to bring the chest off the bal. [6] |

Reverse bridge [6] [6]

|

Goal: Strengthen back and hip muscles while increasing leg motion control. Start position: high position of the reverse bridge movement. The patient has to roll the ball toward herself by flexing her knees and hips and roll it away by extending her legs again. [6] |

Wall sit [6] [6]

|

Goal: Prepare the body for lifting while strengthening the legs to provide power for the lift. Start position: ball between back and wall. 1) Sitting position while rolling the ball down the wall. When he achieves 90° hip and knee flexion, the patient needs to hold the position. 2) Single-leg wall sit, straightening on leg at the knee. [6] |

Exersice with unstable Base[edit | edit source]

Throwing and catching on a mobile surface [6] [6]

|

Goal: develop rapid-onset back stability. Throwing and catching a bal on a mobil surface while you try to stabilize it.The aim is to align the lumbar spine optimally. [6] |

Sitting pelvic tilt, progressing to balance board [6] [6]

|

Goal: advanced control of pelvic tilt. The patient needs to sit down on a wooden bench with the feets on the floor. Than hold the pelvis alternately in the anterior and then posterior direction. The aim is to isolate the pelvis and lower lumbar spine from the thoracic spine and the shoulders from the upper lumbar spine. Maintain the position of the shoulders and thoracic spine. [6] |

Neutral position maintenance [6] [6]

|

Goal: build stability reaction speed in sitting. The patient has to try to balance his body while a person knock the patient. The patient sits in a neutral position on a wobble board. Work gradually up the pressure. [6] |

Lower extremity muscle exercises[edit | edit source]

It is possible that lumbar instability is not only limited to the lumbar spine and its associated anatomical structures. For instance, sacro-iliac joint instability also plays a part and can be the cause of low back pain. Studies have found that a big contributor to this sacro-iliac joint instability and low back pain is the malrecruitment of gluteus maximus and biceps femoris.[19],[16]

The patient has to perform a few slow hip extensions. The physiotherapist places one hand on gluteus maximus of the patient and one on the hamstrings for feedback. If done correctly, the therapist will feel the hand on gluteus maximus being pushed away before the hamstrings are activated.

It has been shown that there is a relationship, especially in muscle coordination, between the muscles that stabilize the lumbar spine and the muscles in the lower extremity. These muscles therefore should be trained as well in order to further achieve a balanced and coordinated muscular system.[16]The quadriceps also play a part in this relationship. A study has found that patients with low back pain have deteriorating function of the quadriceps, with reduced endurance and feedforward compared to normal. The study found that this is due to reduced quadriceps activation after localized lumbar paraspinal fatiguing isometric exercise. Exercises aimed at localized fatigue of the lumbar spine extensors have shown an immediate response in the lower extremity including reduced quadriceps central activation ratio deteriorated balance and response to a balance perturbation. Furthermore they describe a quadriceps fatigability during maximal effort isokinetic knee extension contractions.[20] The two main functions of the quadriceps are extension of the knee and flexion of the hip.

The patient starts with both his feet on the ground. The patient then straightens one leg and holds this position for about 10 seconds before switching legs. To make this exercise a loaded exercise, the patient can do this exercise with weights (for instance on a leg extension machine). Ask the patient to hold for 1-3 seconds.

Exercises for patients who are braced[edit | edit source]

It has been shown that patients who are braced with an orthosis for lumbar instability benefit from some of the exercises described above. A study found that patients who were braced and did the following exercises had a decreased level of pain.

- Gluteal and ischiocrural stretching exercises performed in an unloaded way.

- Contraction exercises of the lumbar stabilizing muscles, in particular transversus abdominus.

- Exercises for trunk stabilization on ever more reduced supporting surfaces and finally on unstable surfaces.[7]

Stabiliser[edit | edit source]

Depending on treatment findings, a patient may need to start with some basic muscle activation. A stabiliser has come into general use for stabilisation exercises for all parts of the body. A stabiliser is a pressure biofeedback unit and consists of an inelastic, three-section air-filled bag, which is inflated to fill the space between the target body area, a firm surface and a pressure dial for monitoring the pressure in the bag for feedback on position. The bag is inflated to an appropriate level for the purpose and the pressure recorded. Movement of the body part off the bag results in a decrease in pressure while movement of the body part into the bag results in an increase in pressure. Its use in assessing the abdominal drawing-in action has become its most important use in relation to the treatment of problems for the local muscle system in patients with low back pain. [13]

The patient is position in hook-lying. The feet remain flat and the arms are held alongside the body. The stabiliser is positioned under the lumbar lordosis. During exercises the spine cannot make any movements. The transversus abdominis is contracted while doing the exercises to maintain an appropriate position. Below the woman is holding the feedback unit to monitor the amplitude of her spinal movement (based on the pressure change on the dial). [20], [6]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Fritz et al. examined the predictive validity of lumbar segmental mobility in patients with LBP. It is possible that patients with segmental hypermobility were more likely to achieve clinical success with stabilization exercises compared with patients without hypermobility.[20]

It has been showed in the research of Hides et al. that the Lumbar Multifidus muscle remained atrophied after a 10-week period when patients with acute LBP did not exercise. But this muscle was recovered to normal size in patients who received a stabilisation exercise program that stressed deep abdominal and isolated the Lumbar Multifidus muscle contractions.[6]

In the study of Richard A et al. some patient groups demonstrated hypertrophy of the Lumbar Multifidus muscles with low-load stabilisation exercises. There are indications that the Lumbar Multifidus muscle is inhibited in patients with LBP and the retraining of the muscle to contract may be the major importance during stabilisation training. [7]

There are also indications that many exercises commonly used by physical therapists in LBP rehabilitation require low to moderate muscle activity of the Lumbar Multifidus and Longissimus thoracicus muscles. To increase the activity of these muscles during exercise, active or resisted lumbar extension is required. Resisted lumbar extension at the end range tends to maximum activity of these muscles.[7]

It has been showed that segmental stabilisation exercise was more effective than placebo intervention in symptomatic lumbar segmental instability.[8]

It also has been showed that specific muscle stabilisation retraining is more relevant for patients with either gross spinal symptoms or pronounced side to side differences in the size of the multifidus muscle than for patients that have no signals of instability. [9]

The mode of action of stabilisation retraining still remains unclear. It has not been shown to be capable of mechanically containing an unstable segment, even upon improvement of muscle activation. No direct long-term effect of stabilisation exercises on the status of the local stabilising muscles has been demonstrated. [9]

The commission advises of a study that evaluated the effect of unstable and unilateral resistance exercises on trunk muscle activation revealed that, regardless of stability, the superman exercise was the most effective trunk-stabiliser exercise for back-stabiliser activation. The side bridge was the optimal exercise for lower-abdominal muscle activation. Thus, the most effective means for trunk strengthening should involve back or abdominal exercises with unstable bases. Furthermore, trunk strengthening can also occur when performing resistance exercises for the limbs, if the exercises are performed unilaterally.[11]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

On this page there are a lot of exercises. To be sure the patients stays motivated it’s important to take care of variation in the exercises you give. It’s possible using this page and your clinical reasoning to vary your therapy for patients with low back pain.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Biely S, Smith S, Silfies S, Clinical Instability of the Lumbar Spine: Diagnosis and Intervention. Orthopaedic Practice. 2006;18(3):6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Davarian S. et al.; Trunk muscles strength and endurance in chronic low back pain patients with and without clinical instability; Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation; 2012 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Niederer D, Engel T, Vogt L, Arampatzis A, Banzer W, Beck H, Moreno Catalá M, Brenner-Fliesser M, Güthoff C, Haag T, Hönning A, Pfeifer AC, Platen P, Schiltenwolf M, Schneider C, Trompeter K, Wippert PM, Mayer F. Motor Control Stabilisation Exercise for Patients with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Prospective Meta-Analysis with Multilevel Meta-Regressions on Intervention Effects. J Clin Med. 2020 Sep 22;9(9):3058.

- ↑ Owen PJ, Miller CT, Mundell NL, Verswijveren SJJM, Tagliaferri SD, Brisby H, Bowe SJ, Belavy DL. Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Nov;54(21):1279-1287.

- ↑ Studnicka K, Ampat G. Lumbar Stabilization. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2020.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 6.31 6.32 6.33 6.34 6.35 6.36 6.37 6.38 6.39 6.40 6.41 6.42 6.43 6.44 6.45 6.46 6.47 6.48 6.49 6.50 6.51 C. M. Norris; Back stability: integrating science and therapy; p. 63, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134,135, 140,146,149,158-161,168-171, 173,175,177,180, 181, 185, 190, 194, 196, 197, 200,205, 207, 210, 211, 215,236,242,243; 2008 (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Celestini M, Marchese A, Serenelli A, Graziani G. A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of physical exercise in patients braced for instability of the lumbar spine. Eura Medicophys. 2005;41: 223-231. (level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hicks GE., Fritz JM., Delitto A., McGill SM. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program, Arch Phys Med Rehabilitation 2005; 86; 1753-1762 (level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Rackwitz et al.; Practicability of segmental stabilizing exercises in the context of a group program for the secondary prevention of low back pain. An explorative pilot study; eura medicophys; 2007 (Level of evidence 3B)

- ↑ Gomes-Neto M, Lopes JM, Conceição CS, Araujo A, Brasileiro A et al. Stabilization exercise compared to general exercises or manual therapy for the management of low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2017; 23:136-142 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.08.004

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Javadian Y et al.; The effects of stabilizing exercises on pain and disability of patients with lumbar segmental instability; J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil.; 2012 (Level of evidence1B)

- ↑ Searle A, Spink M, Ho A, Chuter V. Exercise interventions for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2015;29(12):1155-1167

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 C. Richardson et al.; Therapeutic exercise for lumbopelvic stabilization: A motor control approach for the treatment and prevention of low back pain; p. 177-178, 180-181, 186; Churchill Livingstone; 2004 (Level of evidence5)

- ↑ online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqwx6uCwhUQ, last accessed 6/2/09

- ↑ online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fkt1TOn1UfI, last accessed 6/2/09

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Lamounier Sakamoto AC, et al,. Muscular activation patterns during active prone hip extension exercises. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2009;19:105–112. (level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJ63XJQbp7k, last accessed 6/2/09

- ↑ online video, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsJ7smHAyJk, last accessed 6/2/09

- ↑ http://www.ibodz.com/exercise/gluteal-stretch. Consulted on 30-11-2013 (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 http://protherapysupplies.blogspot.be/2010/11/pro-therapy-supplies-carries.html (Level of evidence 5)