Developmental Coordination Disorder and Physical Activity: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Romy Hageman (talk | contribs) (added some newer literature and added internal physiopedia links) |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== What is Developmental Coordination Disorder? == | == What is Developmental Coordination Disorder? == | ||

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a diagnosis given to children who have marked impairment in motor coordination that significantly impacts on their academic achievement and activities of daily living and is not due to any known medical or mental condition as stated in the DSM-5.<ref name="APA 2000">Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2013;21:591-643.</ref> | [[Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD)|Developmental coordination disorder (DCD)]] is a diagnosis given to children who have marked impairment in motor coordination that significantly impacts on their academic achievement and activities of daily living and is not due to any known medical or mental condition as stated in the DSM-5.<ref name="APA 2000">Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2013;21:591-643.</ref> | ||

According to the DSM-5, the diagnostic criteria for DCD includes the following<ref name="APA 2000" />: | According to the DSM-5, the diagnostic criteria for DCD includes the following<ref name="APA 2000" />: | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

== Etiology == | == Etiology == | ||

Motor control processes depend on the integrated functioning of the sensory, perceptual, cognitive and motor systems. It is, therefore, difficult to determine the location and nature of this neural deficiency.<ref>Edwards J, Berube M, Erlandson K, Haug S, Johnstone H, Meagher, M, Sarkodee-Adoo S, Zwicker, J. Developmental Coordination Disorder in school-aged children born very preterm and/or at very low birth weight: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Nov/Dec 2011; 32(9):678-687.</ref> The heterogenous presentation of DCD also makes it to challenging to identify the pathophsiology. It has been hypothesized that reduced activation of the [[Parietal Lobe|parietal cortex]] and [[cerebellum]] may contribute to signs and symptoms of DCD, including compromised manual dexterity. <ref>Fuelscher I, Caeyenberghs K, Enticott PG, Williams J, Lum J, Hyde C. Differential activation of brain areas in children with developmental coordination disorder during tasks of manual dexterity: an ALE meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018 Mar 1;86:77-84.</ref> In addition, current evidence reports a significantly higher risk in premature and/low birth weight children, those with delayed walking after 15 months and abnormalities in neurotransmission. <ref>Faebo Larsen R, Hvas Mortensen L, Martinussen Torben, Nybo Andersen A. determinants of developmental coordination disorder in 7-year old children: a study of children in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2013;55(11);1016-1022.</ref> | Motor control processes depend on the integrated functioning of the [[Sensory Integration|sensory]], perceptual, cognitive and motor systems. It is, therefore, difficult to determine the location and nature of this neural deficiency.<ref>Edwards J, Berube M, Erlandson K, Haug S, Johnstone H, Meagher, M, Sarkodee-Adoo S, Zwicker, J. Developmental Coordination Disorder in school-aged children born very preterm and/or at very low birth weight: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Nov/Dec 2011; 32(9):678-687.</ref> The heterogenous presentation of DCD also makes it to challenging to identify the pathophsiology. It has been hypothesized that reduced activation of the [[Parietal Lobe|parietal cortex]] and [[cerebellum]] may contribute to signs and symptoms of DCD, including compromised manual dexterity. <ref>Fuelscher I, Caeyenberghs K, Enticott PG, Williams J, Lum J, Hyde C. Differential activation of brain areas in children with developmental coordination disorder during tasks of manual dexterity: an ALE meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018 Mar 1;86:77-84.</ref> In addition, current evidence reports a significantly higher risk in [[Prematurity and High-Risk Infants|premature]] and/low birth weight children, those with delayed walking after 15 months and abnormalities in neurotransmission. <ref>Faebo Larsen R, Hvas Mortensen L, Martinussen Torben, Nybo Andersen A. determinants of developmental coordination disorder in 7-year old children: a study of children in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2013;55(11);1016-1022.</ref> | ||

== Characteristics of DCD == | == Characteristics of DCD == | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

|Handwriting | |Handwriting | ||

|Poor awareness of body position in space | |Poor awareness of body position in space | ||

|Learning disabilities | |[[Communication and Learning Disabilities|Learning disabilities]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Immature balance reactions | |Immature balance reactions | ||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

== Measurement of DCD == | == Measurement of DCD == | ||

There is currently no gold standard for the measurement of DCD. Common outcome measures that can be used by a physiotherapist to measure its severity and impact include; | There is currently no gold standard for the measurement of DCD. Common outcome measures that can be used by a physiotherapist to measure its severity and impact include; | ||

* Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCD-Q) | * Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCD-Q)<ref>van der Linde BW, van Netten JJ, Otten BE, Postema K, Geuze RH, Schoemaker MM. Psychometric properties of the DCDDaily-Q: a new parental questionnaire on children's performance in activities of daily living. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014; 35(7): 1711-9</ref> | ||

* Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC-2) | * [[Movement Assessment Battery for Children|Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC-2)]]<ref>Henderson S, Sugden D, Barnett A. Movement assessment battery for children-2 (MABC-2), 2nd edn. The Psychological Corporation. Harcourt Brace and Company Publishers. London; 2007</ref> | ||

* Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP) | * Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP)<ref>Bruininks RH, Bruininks BD. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2). APA PsycTests. 2005</ref> | ||

* BOT-SF (Short Form) | * BOT-SF (Short Form)<ref>Jírovec J, Musàlek M, Mess F. [https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2019.00153/full Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition (BOT-2): Compatibility of the Complete and Short Form and Its Usefulness for Middle-Age School Children]. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2019; 7: 2296-2360</ref> | ||

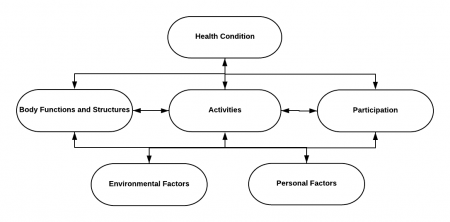

[[File:ICF Model Generic (correct version).png|thumb|450x450px|International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF model)]] | [[File:ICF Model Generic (correct version).png|thumb|450x450px|International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF model)]] | ||

== Why is Participation in Physical Activity Important? == | == Why is Participation in Physical Activity Important? == | ||

The International Classification of Function, Disability and Health ([[International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)|ICF model]]) considers not only the impairment of a condition, but the impact of activity limitations and participation restrictions on disability. <ref name="WHO 2001">World Health Organisation (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health, available: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [accessed 1 April 2012]</ref> Studies investigating participation of children with DCD have indicated decreased physical activity (PA) and fitness. <ref name="Rivilis et al 2011">Rivilis, I., Hay, J., Cairney, J., Klentrous, P., Liu, J. and Faught, B.E. (2011) ‘Physical activity and fitness in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review’, Research in developmental Disabilities, 32(3), 894-910, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 8 Mar 2012]</ref> This may negatively influence not only physical health, <ref name="Rivilis et al 2011" /> but also mental health and social development in children with DCD. <ref name="Hands and Larkin 2002" /> | The International Classification of Function, Disability and Health ([[International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)|ICF model]]) considers not only the impairment of a condition, but the impact of activity limitations and participation restrictions on disability. <ref name="WHO 2001">World Health Organisation (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health, available: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [accessed 1 April 2012]</ref> Studies investigating participation of children with DCD have indicated decreased [[Physical Activity|physical activity (PA)]] and fitness. <ref name="Rivilis et al 2011">Rivilis, I., Hay, J., Cairney, J., Klentrous, P., Liu, J. and Faught, B.E. (2011) ‘Physical activity and fitness in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review’, Research in developmental Disabilities, 32(3), 894-910, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 8 Mar 2012]</ref> This may negatively influence not only physical health, <ref name="Rivilis et al 2011" /> but also [[Mental Health|mental health]] and social development in children with DCD. <ref name="Hands and Larkin 2002" /> They also enjoy PA less than their peirs.<ref name=":0">Farhat F, Denysschien M, Mezghani N, Kammoun MM, Gharbi A, Rebai H, Moalla W, Smits-Engelsman B. [https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0299646 Activities of daily living, self-efficacy and motor skill related fitness and the interrelation in children with moderate and severe Developmental Coordination Disorder]. PLos ONE. 2024; 19(4): e0299646</ref> | ||

== Outcome Measures == | == Outcome Measures == | ||

Studies of PA use subjective methods, such as questionnaires and diaries or objective measures, such as accelerometers. Objective measures tend to be more reliable, but typically only measure frequency and intensity of activity. <ref name="Green et al 2011">Green, D., Lingam, R., Mattocks, C., Riddoch, C., Ness, A. and Emond, A. (2011) ‘The risk of reduced physical activity in children with probable developmental coordination disorder: a prospective longitudinal study’, Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1332-1342, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 5 Mar 2012]</ref> Subjective methods are less reliable and error in reporting occurs. <ref name="Dockrell et al 2000">Dockrell, J., Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G. (2000) ‘Researching children’s perspectives: a psychological dimension’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching Children’s Perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 46-58</ref> However, they can address numerous aspects of PA participation such as diversity, intensity, frequency, enjoyment and whether they participate in group activities or choose solitary activities. <ref name="Jarus et al 2011">Jarus, T., Lourie-Gelberg, Y., Engel-Yeger, B. and Bart, O. (2011) ‘Participation patterns in school-aged children with and without DCD’, Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1323-1331, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 20 Mar 2012]</ref> There is a bias toward parent and teacher-reported PA participation in children with DCD in the literature. <ref name="Magalhaes et al 2011">Magalhaes, L.C., Cardoso, A.A. and Missiuna, C. (2011) ‘Activities and participation in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review’, Research in developmental disabilities,32(4), 1309-1316, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 8 Mar 2011]</ref> It is important to consider children's perspectives and priorities, as they do not mirror that reported by adults. <ref name="Lloyd-smith and Tarr 2000">Lloyd-Smith, M. and Tarr, J. (2000) ‘Researching children’s perspectives: a sociological dimension’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching Children’s Perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 59-70</ref><ref name="Pollock and Stewart 1998">Pollock, N. and Stewart, D. (1998) ‘Occupational performance needs of school-aged children with physical disabilities in the community’, Physical and occupational therapy in pediatrics, 18(1), 55-68, available: Informa Healthcare [accessed 20 Mar 2012]</ref>. Therefore, it may be beneficial to focus research on the perceptive of children with DCD, rather than relying only on caregiver and teacher report. <ref name="Winn-Oakley 2000">Winn-Oakley, M. (2000) ‘Children and young people and care proceedings’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching children’s perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 73-85</ref> | Studies of PA use subjective methods, such as questionnaires and diaries or objective measures, such as [[Accelerometers in Rehabilitation|accelerometers]]. Objective measures tend to be more reliable, but typically only measure frequency and intensity of activity. <ref name="Green et al 2011">Green, D., Lingam, R., Mattocks, C., Riddoch, C., Ness, A. and Emond, A. (2011) ‘The risk of reduced physical activity in children with probable developmental coordination disorder: a prospective longitudinal study’, Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1332-1342, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 5 Mar 2012]</ref> Subjective methods are less reliable and error in reporting occurs. <ref name="Dockrell et al 2000">Dockrell, J., Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G. (2000) ‘Researching children’s perspectives: a psychological dimension’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching Children’s Perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 46-58</ref> However, they can address numerous aspects of PA participation such as diversity, intensity, frequency, enjoyment and whether they participate in group activities or choose solitary activities. <ref name="Jarus et al 2011">Jarus, T., Lourie-Gelberg, Y., Engel-Yeger, B. and Bart, O. (2011) ‘Participation patterns in school-aged children with and without DCD’, Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1323-1331, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 20 Mar 2012]</ref> There is a bias toward parent and teacher-reported PA participation in children with DCD in the literature. <ref name="Magalhaes et al 2011">Magalhaes, L.C., Cardoso, A.A. and Missiuna, C. (2011) ‘Activities and participation in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review’, Research in developmental disabilities,32(4), 1309-1316, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 8 Mar 2011]</ref> It is important to consider children's perspectives and priorities, as they do not mirror that reported by adults. <ref name="Lloyd-smith and Tarr 2000">Lloyd-Smith, M. and Tarr, J. (2000) ‘Researching children’s perspectives: a sociological dimension’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching Children’s Perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 59-70</ref><ref name="Pollock and Stewart 1998">Pollock, N. and Stewart, D. (1998) ‘Occupational performance needs of school-aged children with physical disabilities in the community’, Physical and occupational therapy in pediatrics, 18(1), 55-68, available: Informa Healthcare [accessed 20 Mar 2012]</ref>. Therefore, it may be beneficial to focus research on the perceptive of children with DCD, rather than relying only on caregiver and teacher report. <ref name="Winn-Oakley 2000">Winn-Oakley, M. (2000) ‘Children and young people and care proceedings’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching children’s perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 73-85</ref> | ||

* PERF-Fit battery: a functional measure of motor skill-related fitness<ref>Smits-Engelsman BCM. Developing a motor PERFormance and physical FITness test battery for low resourced communities (2nd ed.). Cape Town: PERF-FITT</ref>. | |||

** [[Psychometric Properties|Psychometric properties]]<ref>Smits-Engelsman B, Bonney E, Neto JLC, Jelsma DL. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12889-020-09236-w Feasibility and content validity of the PERF-FIT test battery to assess movement skills, agility and power among children in low-resource settings]. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1): 1-11</ref><ref>Smits-Engelsman B, Smit E, Doe-Asinyo RX, Lawerteh SE, Aertssen W, Ferguson G. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12887-021-02589-0 Inter-rater reliability and test-retest reliability of the Performance and Fitness (PERF-FIT) test battery for children: a test for motor skill related fitness]. BMC Pediatrics. 2021; 21(1): 1-11</ref>: | |||

*** It is a valid and reliable test for children (5-12 years old) | |||

*** Excellent content validity (0.86 to 1.00) | |||

*** Good structural validity | |||

*** Excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC 0.99) | |||

*** Good test-retest reliability (ICC > 0.80) | |||

== Frequency of Participation in PA == | == Frequency of Participation in PA == | ||

Frequency of participation in PA is reduced in this population of children. Children with DCD between the age of 9 and 14 years report lower frequency of participation in free-and organised-play. <ref name="Cairney et al">Cairney, J., Hay, J.A., Faught, B.E., Wade, T.J., Corna, L. and Flours, A. (2005a) ‘Developmental coordination disorder, generalized self-efficacy toward physical activity, and participation in organized and free play activities’, The journal of paediatrics, 147(4), 515-520, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> <ref name="Fong et al 2011">Fong, S.S.M., Lee, V.Y.L., Chan, N.N.C., Chan, R.S.H., Chak, W. and Pang, M.Y.C. (2011) ‘Motor ability and weight status are determinants of out-of-school activity participation for children with developmental coordination disorder’, Research in developmental disabilities,32(6), available: ScienceDirect [accessed 5 Mar 2012]</ref> Fong et al. and Jarus et al. agreed with this finding for children aged between 6 and 12 years and 5 and 7 years, respectively.<ref name="Fong et al 2011" /><ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> Cairney et al. and Jarus et al. both used small sample sizes of children that were not randomly selected. <ref name="Cairney et al" /> <ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> Fong et al. had a larger sample based on statistical power calculations.<ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> This was the only study to calculate sample size based on statistical power, but the sample was still a convenience sample. Therefore there is a risk of selection bias in these studies. While Jarus et al. <ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> and Fong et al. <ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> had a sample of children with a diagnosis of DCD, those included in Cairney et al. <ref name="Cairney et al" /> were not given a formal diagnosis. Only one other study used a sample of children with a formal diagnosis of DCD. <ref name="Engel-Yeger 2010">Engel-Yeger, B. and Hanna Kasis (2010) ‘The relationship between developmental coordination disorder, child’s perceived self-efficacy and preference to participate in daily activities’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(5), 670-677, available: Wiley Online Library [accessed 5 Mar 2012]</ref> None of the studies blinded the investigators, which may lead to detection bias. Frequency of PA participation was consistently reduced in all studies of children with DCD. | Frequency of participation in PA is reduced in this population of children<ref name=":0" /><ref>Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, Rodriguez MC, King-Dowling S, Kwan MY, Wade T. [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/9/e029784.abstract Cohort profile: the Canadian coordination and activity tracking in children (CATCH) longitudinal cohort.] BMJ open. 2019; 9(9): e029784</ref><ref>Doe-Asinyo RX, Smits-Engelsman BC. [https://www.cell.com/heliyon/pdf/S2405-8440(21)02004-1.pdf Ecological validity of the PERF-FIT: Correlates of active play, motor performance and motor skill-related physical fitness]. Heliyon. 2021; 7(8): 34504965</ref><ref>Mercê C, Cordeìro J, Romão C, Caloço Branco MA, Catela D. Deficits in Physical Activity Behaviour in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. 2023; 47: 1988-2041</ref>. Children with DCD between the age of 9 and 14 years report lower frequency of participation in free-and organised-play. <ref name="Cairney et al">Cairney, J., Hay, J.A., Faught, B.E., Wade, T.J., Corna, L. and Flours, A. (2005a) ‘Developmental coordination disorder, generalized self-efficacy toward physical activity, and participation in organized and free play activities’, The journal of paediatrics, 147(4), 515-520, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> <ref name="Fong et al 2011">Fong, S.S.M., Lee, V.Y.L., Chan, N.N.C., Chan, R.S.H., Chak, W. and Pang, M.Y.C. (2011) ‘Motor ability and weight status are determinants of out-of-school activity participation for children with developmental coordination disorder’, Research in developmental disabilities,32(6), available: ScienceDirect [accessed 5 Mar 2012]</ref> Fong et al. and Jarus et al. agreed with this finding for children aged between 6 and 12 years and 5 and 7 years, respectively.<ref name="Fong et al 2011" /><ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> Cairney et al. and Jarus et al. both used small sample sizes of children that were not randomly selected. <ref name="Cairney et al" /> <ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> Fong et al. had a larger sample based on statistical power calculations.<ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> This was the only study to calculate sample size based on statistical power, but the sample was still a convenience sample. Therefore there is a risk of selection bias in these studies. While Jarus et al. <ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> and Fong et al. <ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> had a sample of children with a diagnosis of DCD, those included in Cairney et al. <ref name="Cairney et al" /> were not given a formal diagnosis. Only one other study used a sample of children with a formal diagnosis of DCD. <ref name="Engel-Yeger 2010">Engel-Yeger, B. and Hanna Kasis (2010) ‘The relationship between developmental coordination disorder, child’s perceived self-efficacy and preference to participate in daily activities’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(5), 670-677, available: Wiley Online Library [accessed 5 Mar 2012]</ref> None of the studies blinded the investigators, which may lead to detection bias. Frequency of PA participation was consistently reduced in all studies of children with DCD. They also spent less time engaged in moderate to vigorous activities<ref>Braaksma P, Stuive I, Eibrink JW, Snoeren L, Postuma EMJL, Dekker R, van der Sluis CK, Schoemaker MM. [https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/111900179/Complete_thesis.pdf#page=154 Participation in recreational and leisure activities of 4-12-year-old children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review.] University of Groningen. 2020</ref>. | ||

== Intensity of Participation in PA == | == Intensity of Participation in PA == | ||

Poulsen et al. reported that adolescent boys with DCD spent decreased time in high-intensity PA and had a preference for low-intensity PA compared to boys without DCD.<ref name="Poulsen et al">Poulsen, A.A., Ziviani, J.M., Johnson, H. and Cuskelly, M. (2008a) ‘Loneliness and life satisfaction of boys with developmental coordination disorder: the impact of leisure participation and perceived freedom in leisure’, Human movement science, 27(2), 325-343, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> This was estimated from a one-week diary log of PA which has a high risk of reporting error as it relies on recall abilities of participants. <ref name="Anderson et al 2005">Anderson, C.P., Hagstromer, M. and Yngve, A. (2005) ‘Validation of the PDPAR as an adolescent diary: Effect of accelerometer cut points’, Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 37(7), 1224-1230, available: OvidSP [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> Jarus et al. and Fong et al. included both genders and reported decreased intensity of PA in children with DCD.<ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> <ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> These results can be considered more reliable, as they were calculated using the Child Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) questionnaire.<ref name="King et al 2007">King, G., Law, M., King, S., Hurley, P., Hanna, S., Kertoy, M. and Rosenbaum, P. (2007) ‘Measuring children’s participation in recreational and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(1), 28-39, available: CINAHL</ref> Both studies matched controls and participants for age, gender and socio-economic class, but like the other studies in this review, they did not account for other confounding variables such as birth weight, gestational age or maternal PA levels during pregnancy in the statistical analyses, which have been shown to influence PA in childhood. <ref name="Mattocks et al 2008">Mattocks, C., Ness, A., Deere, K., Leary, S., Tilling, K., Blair, S.N. and Riddoch, C. (2008) ‘Early determinants of physical activity in 11 to 12 year olds: cohort study’, British Medical Journal, 336(7634), 26-29, available: JSTOR</ref> Differences in PA may, therefore, be due to factors other than DCD. | Poulsen et al. reported that adolescent boys with DCD spent decreased time in high-intensity PA and had a preference for low-intensity PA compared to boys without DCD.<ref name="Poulsen et al">Poulsen, A.A., Ziviani, J.M., Johnson, H. and Cuskelly, M. (2008a) ‘Loneliness and life satisfaction of boys with developmental coordination disorder: the impact of leisure participation and perceived freedom in leisure’, Human movement science, 27(2), 325-343, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> This was estimated from a one-week diary log of PA which has a high risk of reporting error as it relies on recall abilities of participants. <ref name="Anderson et al 2005">Anderson, C.P., Hagstromer, M. and Yngve, A. (2005) ‘Validation of the PDPAR as an adolescent diary: Effect of accelerometer cut points’, Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 37(7), 1224-1230, available: OvidSP [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> Jarus et al. and Fong et al. included both genders and reported decreased intensity of PA in children with DCD.<ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> <ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> These results can be considered more reliable, as they were calculated using the Child Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) questionnaire.<ref name="King et al 2007">King, G., Law, M., King, S., Hurley, P., Hanna, S., Kertoy, M. and Rosenbaum, P. (2007) ‘Measuring children’s participation in recreational and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(1), 28-39, available: CINAHL</ref> Both studies matched controls and participants for age, gender and socio-economic class, but like the other studies in this review, they did not account for other confounding variables such as birth weight, gestational age or maternal PA levels during pregnancy in the statistical analyses, which have been shown to influence PA in childhood. <ref name="Mattocks et al 2008">Mattocks, C., Ness, A., Deere, K., Leary, S., Tilling, K., Blair, S.N. and Riddoch, C. (2008) ‘Early determinants of physical activity in 11 to 12 year olds: cohort study’, British Medical Journal, 336(7634), 26-29, available: JSTOR</ref> Differences in PA may, therefore, be due to factors other than DCD. At the same time, children with DCD present significantly lower physical fitness that their typically developing peers: mostly in [[Aerobic Exercise|aerobic]]/[[Anaerobic Capacity|anaerobic capacity]] and in muscle strength<ref>Cavalcante Neto JL, Draghi TTG, Santos IWP, Brito R, Da S, Silva LS, de O, Lima US. Physical Fitness in Children With Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Systematic Review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2024; 1-30</ref>. | ||

== Diversity of Participation in PA == | == Diversity of Participation in PA == | ||

| Line 120: | Line 128: | ||

== Effect of Age on Participation Patterns == | == Effect of Age on Participation Patterns == | ||

It has been suggested that the activity-deficit in children with DCD may increase with age.<ref name="Wall 2004">Wall, A.E. (2004) ‘The development of skill learning gap hypothesis: implications for children with movement difficulties’, Adapted physical activity quarterly, 21(3), 197-218, available: SPORTDiscus</ref> This was not seen in children between the age of 9 and 14 years in free- and organised-play. <ref name="Cairney et al" /> Appropriate ANCOVA tests were used to analyse this difference, but results should be interpreted with caution, as this study was cross-sectional. More accurate results would be obtained from a longitudinal study following the same group of children, rather than comparing results from different individuals at different ages. The only longitudinal study in this review used mixed-effects modelling analysis, which showed a difference over a 3 year period.<ref name="Cairney et al" /> Boys showed an increase in the frequency of PA, while girls exhibited a consistent decrease. The increasing expectations and complexity of PA in adolescence were cited as a challenge.<ref name="Missiuna et al 2008">Missiuna, C., Moll, S., King, G., Stewart, D. and MacDonald, K. (2008) ‘Life experiences of young adults who have coordination difficulties’, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(3), 157-166</ref> The sample used in this qualitative study was a group of university students which is not representative of the wider heterogeneous population of children with DCD. However, it is important to consider qualitative research as it gives a deeper meaning to the reduced participation in this population. | It has been suggested that the activity-deficit in children with DCD may increase with age.<ref name="Wall 2004">Wall, A.E. (2004) ‘The development of skill learning gap hypothesis: implications for children with movement difficulties’, Adapted physical activity quarterly, 21(3), 197-218, available: SPORTDiscus</ref> This was not seen in children between the age of 9 and 14 years in free- and organised-play. <ref name="Cairney et al" /> Young children with DCD are not participating less than their peers. This might be due to the low motor skill requirements of play and sport at this age level<ref>King-Dowling S, Kwan MYW, Rodriguez C, Missiuna C, Timmons BW, Cairney J. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dmcn.14237 Physical activity in young children at risk for developmental coordination disorder.] Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2019; 61: 1302-1308</ref>. Appropriate ANCOVA tests were used to analyse this difference, but results should be interpreted with caution, as this study was cross-sectional. More accurate results would be obtained from a longitudinal study following the same group of children, rather than comparing results from different individuals at different ages. The only longitudinal study in this review used mixed-effects modelling analysis, which showed a difference over a 3 year period.<ref name="Cairney et al" /> Boys showed an increase in the frequency of PA, while girls exhibited a consistent decrease. The increasing expectations and complexity of PA in adolescence were cited as a challenge.<ref name="Missiuna et al 2008">Missiuna, C., Moll, S., King, G., Stewart, D. and MacDonald, K. (2008) ‘Life experiences of young adults who have coordination difficulties’, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(3), 157-166</ref> The sample used in this qualitative study was a group of university students which is not representative of the wider heterogeneous population of children with DCD. However, it is important to consider qualitative research as it gives a deeper meaning to the reduced participation in this population. | ||

== Effect of Gender on Participation == | == Effect of Gender on Participation == | ||

| Line 128: | Line 136: | ||

== Effect of Motor Ability on Participation == | == Effect of Motor Ability on Participation == | ||

Motor ability was shown to positively correlate to PA. <ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> Children with DCD have poor motor skills, and therefore often don't feel adequate for physical activity tasks<ref>Le T, Graham JD, King-Dowling S, Cariney J. Perceptions of ability mediate the effect of motor coordination on aerobic and musculoskeletal exercise performance in young children at risk for Developmental Coordination Disorder. Journal of Sports and Exercise Psychology. 2020; 42(5): 407-16</ref>. The influence of inadequate motor skills on individuals' self-confidence, preference for, and enjoyment of physical activities has significant implications for designing interventions, whether the focus is on improving motor skills or reaching fitness objectives<ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /><ref>Li Y-C, Kwan MY, King-Dowling S, Rodriguez MC, Cariney J. Does physical activity and BMI mediate the association between DCD and internalizing problems in early childhood? A partial test of the Environmental Stress Hypothesis. Human Movement Science. 2021; 75: 102744</ref>. These findings suggest that children with higher motor ability have an increased ability to activate and sequence motor movements, which provides more opportunities for participation.<ref name="Wrotniak et al 2006">Wrotniak, B.H., Epstein, L.H., Dorn, J.M., Jones, K.E. and Kondilis, V.A. (2006) ‘The relationship between motor proficiency and physical activity in children’, Pediatrics, 118, (6), 1758-1765</ref> | |||

== Effect of Reduced Participation on Social Development == | == Effect of Reduced Participation on Social Development == | ||

Reduced PA may have a detrimental effect on social development.<ref name="Hands and Larkin 2002">Hands, B. and Larkin, D. (2002) ‘Physical fitness and developmental coordination disorder’, in Cermack, S.A. and Larkin, D., eds., Developmental Coordination Disorder, New York: Delmar Thomson Learning, 172-185</ref> A greater number of children with DCD play alone during out of school activities compared to their peers.<ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> This was reiterated in qualitative studies, where individual activities were preferred as they avoid ridicule and pressure from peers. <ref name="Missiuna et al 2008" /> <ref name="Fitzpatrick and Watkinson 2003">Fitzpatrick, D.A. and Watkinson, E.J. (2003) ‘The lived experience of physical awkwardness: adults’ retrospective views’, Adapted physical activity quarterly, 20(3), 279-297, available: SPORTDiscus [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> Fong et al. concluded that a large number of children in their sample with and without DCD participated in activities with family, demonstrating no difference between groups.<ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> This may be due to cultural influence with more emphasis on family in this Asian sample. <ref name="Kim and Wong 2002">Kim, S.Y. and Wong, V.Y. (2002) ‘Assessing Asian and Asian American parenting: A review of the literature’, in Kurasaki, K., Okazaki, S. and Sue, S., eds., Asian American mental health: Assessment methods and theory, Netherlands; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 185-203</ref> Boys with DCD had a lower perception of their social competence which had a negative impact on the intensity of participation<ref name="Poulsen et al" />. Poulsen et al. found that motor ability affected loneliness negatively and life satisfaction positively in the same group of boys.<ref name="Poulsen et al" /> They discovered that team sport participation increased life satisfaction and decreased loneliness, which is probably due to the social nature of these sports. However, there may be other factors that were not taken into consideration in this study, such as social-environmental influences, because only partial mediation effects were demonstrated. All the participants were males from a high socio-economic background, which may place social value on participation in sports, which may which affect generalizability of results. Additionally, there seems to be a paucity in the literature to support these results, making it difficult to draw causality. | Reduced PA may have a detrimental effect on social development.<ref name="Hands and Larkin 2002">Hands, B. and Larkin, D. (2002) ‘Physical fitness and developmental coordination disorder’, in Cermack, S.A. and Larkin, D., eds., Developmental Coordination Disorder, New York: Delmar Thomson Learning, 172-185</ref> A greater number of children with DCD play alone during out of school activities compared to their peers.<ref name="Jarus et al 2011" /> This was reiterated in qualitative studies, where individual activities were preferred as they avoid ridicule and pressure from peers. <ref name="Missiuna et al 2008" /> <ref name="Fitzpatrick and Watkinson 2003">Fitzpatrick, D.A. and Watkinson, E.J. (2003) ‘The lived experience of physical awkwardness: adults’ retrospective views’, Adapted physical activity quarterly, 20(3), 279-297, available: SPORTDiscus [accessed 6 Mar 2012]</ref> Fong et al. concluded that a large number of children in their sample with and without DCD participated in activities with family, demonstrating no difference between groups.<ref name="Fong et al 2011" /> This may be due to cultural influence with more emphasis on family in this Asian sample. <ref name="Kim and Wong 2002">Kim, S.Y. and Wong, V.Y. (2002) ‘Assessing Asian and Asian American parenting: A review of the literature’, in Kurasaki, K., Okazaki, S. and Sue, S., eds., Asian American mental health: Assessment methods and theory, Netherlands; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 185-203</ref> Boys with DCD had a lower perception of their social competence which had a negative impact on the intensity of participation<ref name="Poulsen et al" />. Poulsen et al. found that motor ability affected loneliness negatively and life satisfaction positively in the same group of boys.<ref name="Poulsen et al" /> They discovered that team sport participation increased life satisfaction and decreased loneliness, which is probably due to the social nature of these sports. However, there may be other factors that were not taken into consideration in this study, such as social-environmental influences, because only partial mediation effects were demonstrated. All the participants were males from a high socio-economic background, which may place social value on participation in sports, which may which affect generalizability of results. Additionally, there seems to be a paucity in the literature to support these results, making it difficult to draw causality. Children with DCD are often the last to be invited to join games or sports, and sometimes they do not participate at all<ref>Noordstar JJ, Volman M. Self-perceptions in children with probable developmental coordination disorder with and without overweight. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020; 99; 103601</ref>. They are often the spectator and excluded due to their low motor competence<ref>Nobre G, Valentini N, Ramalho M, Sartori R. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1875957218303802 Self-efficacy profile in daily activities: Children at risk and with developmental coordination disorder]. Pediatrics & Neonatology. 2019; 60(6): 662-8</ref>. | ||

== Effect of Reduced Participation on Self-Efficacy Towards PA == | == Effect of Reduced Participation on Self-Efficacy Towards PA == | ||

Revision as of 19:38, 1 June 2024

Original Editor Irene Leahy

Top Contributors - Stacy Zousmer, Irene Leahy, Romy Hageman, Kim Jackson, Adam Vallely Farrell, Admin, 127.0.0.1 and Michelle Lee

What is Developmental Coordination Disorder?[edit | edit source]

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a diagnosis given to children who have marked impairment in motor coordination that significantly impacts on their academic achievement and activities of daily living and is not due to any known medical or mental condition as stated in the DSM-5.[1]

According to the DSM-5, the diagnostic criteria for DCD includes the following[1]:

A. The acquisition and execution of coordinated motor skills is substantially below that expected given the individual’s chronological age and opportunity for skill learning and use. Difficulties are manifested as clumsiness (e.g., dropping or bumping into objects) as well as slowness and inaccuracy of performance of motor skills (e.g., catching an object, using scissors or cutlery, handwriting, riding a bike, or participating in sports).

B. The motor skills deficit in Criterion A significantly and persistently interferes with activities of daily living appropriate to chronological age (e.g., self-care and self-maintenance) and impacts academic/school productivity, prevocational and vocational activities, leisure, and play.

C. Onset of symptoms is in the early developmental period.

D. The motor skills deficits are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or visual impairment and are not attributable to a neurological condition affecting movement (e.g., cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, degenerative disorders).

DCD should not be confused with dyspraxia in which there is no formal diagnostic criteria and is not recognised by many paediatricians and school authorities as a diagnosis.

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Developmental coordination disorder is identified as a common disorder of childhood and is usually identified in children between 5 and 11 years of age.[1] In the 1990s researchers estimated that DCD occurred in 10% to 19% of school-aged children.[2] Following a more precise diagnostic criteria and definition, the current prevalence is estimated to be 5%- 8% of all school-aged children.[3] It is more prevalent in boys than in girls (2:1).[4] This difference is often associated with a higher referral rate for boys, because the behaviour of boys with motor incoordination may be more difficult to manage at home and in the classroom.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Motor control processes depend on the integrated functioning of the sensory, perceptual, cognitive and motor systems. It is, therefore, difficult to determine the location and nature of this neural deficiency.[5] The heterogenous presentation of DCD also makes it to challenging to identify the pathophsiology. It has been hypothesized that reduced activation of the parietal cortex and cerebellum may contribute to signs and symptoms of DCD, including compromised manual dexterity. [6] In addition, current evidence reports a significantly higher risk in premature and/low birth weight children, those with delayed walking after 15 months and abnormalities in neurotransmission. [7]

Characteristics of DCD[edit | edit source]

| Gross Motor | Fine Motor | Perceptual/Sensory | Psychosocial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotonia | Handwriting | Poor awareness of body position in space | Learning disabilities |

| Immature balance reactions | Drawing | Poor sense of direction | Reading difficulties |

| Awkward running patterns | Confused about which hand to use | Sensitive to touch | Speech problems |

| Poor posture | Gripping | Find some fabrics uncomfortable | Class clown |

| Frequent falls | Dressing | Few friends | |

| Dropping items | Buttons | Lower self-esteem | |

| Difficulty imitating body positions | Zipping | Increased anxiety | |

| Difficulty following 2-3 stage motor commands | Shoelaces | ||

| Reduced ability to throw/catch ball | |||

| Difficulty hopping, skipping, riding a bike | |||

| Slow to dress |

Measurement of DCD[edit | edit source]

There is currently no gold standard for the measurement of DCD. Common outcome measures that can be used by a physiotherapist to measure its severity and impact include;

- Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCD-Q)[10]

- Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC-2)[11]

- Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP)[12]

- BOT-SF (Short Form)[13]

Why is Participation in Physical Activity Important?[edit | edit source]

The International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF model) considers not only the impairment of a condition, but the impact of activity limitations and participation restrictions on disability. [14] Studies investigating participation of children with DCD have indicated decreased physical activity (PA) and fitness. [15] This may negatively influence not only physical health, [15] but also mental health and social development in children with DCD. [16] They also enjoy PA less than their peirs.[17]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Studies of PA use subjective methods, such as questionnaires and diaries or objective measures, such as accelerometers. Objective measures tend to be more reliable, but typically only measure frequency and intensity of activity. [18] Subjective methods are less reliable and error in reporting occurs. [19] However, they can address numerous aspects of PA participation such as diversity, intensity, frequency, enjoyment and whether they participate in group activities or choose solitary activities. [20] There is a bias toward parent and teacher-reported PA participation in children with DCD in the literature. [21] It is important to consider children's perspectives and priorities, as they do not mirror that reported by adults. [22][23]. Therefore, it may be beneficial to focus research on the perceptive of children with DCD, rather than relying only on caregiver and teacher report. [24]

- PERF-Fit battery: a functional measure of motor skill-related fitness[25].

- Psychometric properties[26][27]:

- It is a valid and reliable test for children (5-12 years old)

- Excellent content validity (0.86 to 1.00)

- Good structural validity

- Excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC 0.99)

- Good test-retest reliability (ICC > 0.80)

- Psychometric properties[26][27]:

Frequency of Participation in PA[edit | edit source]

Frequency of participation in PA is reduced in this population of children[17][28][29][30]. Children with DCD between the age of 9 and 14 years report lower frequency of participation in free-and organised-play. [31] [32] Fong et al. and Jarus et al. agreed with this finding for children aged between 6 and 12 years and 5 and 7 years, respectively.[32][20] Cairney et al. and Jarus et al. both used small sample sizes of children that were not randomly selected. [31] [20] Fong et al. had a larger sample based on statistical power calculations.[32] This was the only study to calculate sample size based on statistical power, but the sample was still a convenience sample. Therefore there is a risk of selection bias in these studies. While Jarus et al. [20] and Fong et al. [32] had a sample of children with a diagnosis of DCD, those included in Cairney et al. [31] were not given a formal diagnosis. Only one other study used a sample of children with a formal diagnosis of DCD. [33] None of the studies blinded the investigators, which may lead to detection bias. Frequency of PA participation was consistently reduced in all studies of children with DCD. They also spent less time engaged in moderate to vigorous activities[34].

Intensity of Participation in PA[edit | edit source]

Poulsen et al. reported that adolescent boys with DCD spent decreased time in high-intensity PA and had a preference for low-intensity PA compared to boys without DCD.[35] This was estimated from a one-week diary log of PA which has a high risk of reporting error as it relies on recall abilities of participants. [36] Jarus et al. and Fong et al. included both genders and reported decreased intensity of PA in children with DCD.[20] [32] These results can be considered more reliable, as they were calculated using the Child Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) questionnaire.[37] Both studies matched controls and participants for age, gender and socio-economic class, but like the other studies in this review, they did not account for other confounding variables such as birth weight, gestational age or maternal PA levels during pregnancy in the statistical analyses, which have been shown to influence PA in childhood. [38] Differences in PA may, therefore, be due to factors other than DCD. At the same time, children with DCD present significantly lower physical fitness that their typically developing peers: mostly in aerobic/anaerobic capacity and in muscle strength[39].

Diversity of Participation in PA[edit | edit source]

Fong et al. reported that children aged 6-12 years participate in a smaller variety of activities. Analysis of results shows that participation is less in informal, physical, social, skill-based and self-improvement activities than their peers without DCD.[32] However, participation in formal and recreational activities did not differ between groups. The majority of recreational activities in the CAPE questionnaire are sedentary and do not require motor coordination. Jarus et al. also used the CAPE questionnaire and found that children aged 5-7 years with DCD engage in less physical, skill-based and informal activities.[20] In contrast, no statistical significant difference was found in social and self-improvement activities. This may be due to the small sample size, as mentioned before. Poulsen et al. measured diversity of activities in boys with DCD over a week.[35] This may not be a reliable measure, due to the short time span. The CAPE questionnaire used by the previous studies considers the diversity of participation over the previous 4 months. Taking this into account, results once again show that boys with DCD participated in less diverse activities and the majority of time was spent in sedentary activities. Participation in team sports and unstructured social physical activities were significantly lower than their peers without DCD. Unstructured social PA included street ball games or running games. Interestingly, there was no difference between groups in individual sports. This may be due to these activities not requiring the evaluative skills needed for team sports.[35] According to a review of the literature, it may be concluded that children with DCD demonstrate a narrower diversity of PA compared to typical children.

Effect of Age on Participation Patterns[edit | edit source]

It has been suggested that the activity-deficit in children with DCD may increase with age.[40] This was not seen in children between the age of 9 and 14 years in free- and organised-play. [31] Young children with DCD are not participating less than their peers. This might be due to the low motor skill requirements of play and sport at this age level[41]. Appropriate ANCOVA tests were used to analyse this difference, but results should be interpreted with caution, as this study was cross-sectional. More accurate results would be obtained from a longitudinal study following the same group of children, rather than comparing results from different individuals at different ages. The only longitudinal study in this review used mixed-effects modelling analysis, which showed a difference over a 3 year period.[31] Boys showed an increase in the frequency of PA, while girls exhibited a consistent decrease. The increasing expectations and complexity of PA in adolescence were cited as a challenge.[42] The sample used in this qualitative study was a group of university students which is not representative of the wider heterogeneous population of children with DCD. However, it is important to consider qualitative research as it gives a deeper meaning to the reduced participation in this population.

Effect of Gender on Participation[edit | edit source]

There are less societal expectations for females to be physically active.[43] It is, therefore, suggested that girls with DCD will be less active than boys with DCD. Cairney et al. found no statistical difference in PA frequency between genders. Despite this, there is a trend towards lower participation in free-and organized-play in girls, but it does not reach statistical significance, which may be due to the smaller sample size. [31] Cairney et al. used a larger sample size and showed that there was increased frequency of PA in boys with DCD compared with girls as they got older. [31] It is important to remember that both these studies used a Participation Questionnaire (PQ) which only accounts for organised- and free-play and not other forms of PA such as chores and active transport. Additionally, Engel-Yeger and Hanna Kasis showed there were differences between genders as far as preference for certain activities.[44] Girls with DCD favoured skill-based activities, whereas boys favoured active PA, which was similar to their peers without DCD. This study, unlike the others, included parent education, as well as age and gender as confounding factors in the analysis. One limitation of this study is the use of Preference for Activities of Children (PAC), as it just measures preference and gives no indication of whether these activities are performed. Therefore, it does not indicate actual participation patterns.

Effect of Motor Ability on Participation[edit | edit source]

Motor ability was shown to positively correlate to PA. [20] Children with DCD have poor motor skills, and therefore often don't feel adequate for physical activity tasks[45]. The influence of inadequate motor skills on individuals' self-confidence, preference for, and enjoyment of physical activities has significant implications for designing interventions, whether the focus is on improving motor skills or reaching fitness objectives[20][46]. These findings suggest that children with higher motor ability have an increased ability to activate and sequence motor movements, which provides more opportunities for participation.[47]

Effect of Reduced Participation on Social Development[edit | edit source]

Reduced PA may have a detrimental effect on social development.[16] A greater number of children with DCD play alone during out of school activities compared to their peers.[20] This was reiterated in qualitative studies, where individual activities were preferred as they avoid ridicule and pressure from peers. [42] [48] Fong et al. concluded that a large number of children in their sample with and without DCD participated in activities with family, demonstrating no difference between groups.[32] This may be due to cultural influence with more emphasis on family in this Asian sample. [49] Boys with DCD had a lower perception of their social competence which had a negative impact on the intensity of participation[35]. Poulsen et al. found that motor ability affected loneliness negatively and life satisfaction positively in the same group of boys.[35] They discovered that team sport participation increased life satisfaction and decreased loneliness, which is probably due to the social nature of these sports. However, there may be other factors that were not taken into consideration in this study, such as social-environmental influences, because only partial mediation effects were demonstrated. All the participants were males from a high socio-economic background, which may place social value on participation in sports, which may which affect generalizability of results. Additionally, there seems to be a paucity in the literature to support these results, making it difficult to draw causality. Children with DCD are often the last to be invited to join games or sports, and sometimes they do not participate at all[50]. They are often the spectator and excluded due to their low motor competence[51].

Effect of Reduced Participation on Self-Efficacy Towards PA[edit | edit source]

Cairney et al. and Engel-Yeger and Hanna Kasis concluded that self-efficacy in children with DCD was significantly lower compared to their peers. [31][44] However, Cairney et al. had a low response rate to the PQ, which may bias results, as there is a lack of data on non-participants.[31] An additional limitation of these studies is that the outcome measures used do not measure efficacy in activities outside of school. Children’s Self-perception of Adequacy in and Predilection for Physical Activity (CSAPPA) measures self-efficacy in physical education class and the Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System (PEGS) include school and self-care activities as well as leisure activities.[31] [44] Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions about self-efficacy in activities outside of school.

Enjoyment of PA and Participation[edit | edit source]

Studies investigating enjoyment of PA report no difference between children with and without DCD. [20] [32] This may be due to the likelihood of children choosing to participate in activities that they enjoyed.[20] These children had not yet reached adolescence, which may have biased the results, as younger children are less likely to compare themselves to peers, and are less likely to be frustrated by their inability to perform.[52] Missiuna et al. indicated that adolescents also chose activities in which they excel and enjoy. [42] Additionally, Fitzpatrick and Watkinson reported avoidance of activities that caused humiliation.[48] Exposure of their awkwardness was likely to have resulted in decreased enjoyment during activities, rather than the lack of coordination. Similar to the research conducted by Missuina et al., this study used a phenomenological approach and considered the retrospective viewpoint of adults through interview. [42] Credibility of thematic analysis was established using member checks for verification of accuracy. Neither study considered the author's role and the bias that this may cause in the data. Participants were not diagnosed with DCD but had significant coordination difficulties that affected daily activities. These studies relied on the recall ability of adults rather than interviewing children. Both studies have limitations, but provide information regarding the children' selection of enjoyable activities. Ultimately, further qualitative research is needed of children with DCD.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2013;21:591-643.

- ↑ Barnhart R, Davenport M, Epps S, Nordquist V. Developmental coordination disorder. Physical Therapy Aug 2003; 83(8); 722-731.

- ↑ Smyth TR. Impaired motor skill (clumsiness) in otherwise normal children: a review. Child Care, Health, and Development. 1992;18:283–300.

- ↑ Gordon N, McKinlay I. Helping clumsy children. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1980.

- ↑ Edwards J, Berube M, Erlandson K, Haug S, Johnstone H, Meagher, M, Sarkodee-Adoo S, Zwicker, J. Developmental Coordination Disorder in school-aged children born very preterm and/or at very low birth weight: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Nov/Dec 2011; 32(9):678-687.

- ↑ Fuelscher I, Caeyenberghs K, Enticott PG, Williams J, Lum J, Hyde C. Differential activation of brain areas in children with developmental coordination disorder during tasks of manual dexterity: an ALE meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018 Mar 1;86:77-84.

- ↑ Faebo Larsen R, Hvas Mortensen L, Martinussen Torben, Nybo Andersen A. determinants of developmental coordination disorder in 7-year old children: a study of children in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2013;55(11);1016-1022.

- ↑ Dewey D, Wilson BN. Developmental coordination disorder: what is it? Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2001;20:5–27.

- ↑ Skinner RA, Piek JP. Psychosocial implications of poor motor coordination in children and adolescents. Hum Mov Sci. 2001;20(1–2): 73–94.

- ↑ van der Linde BW, van Netten JJ, Otten BE, Postema K, Geuze RH, Schoemaker MM. Psychometric properties of the DCDDaily-Q: a new parental questionnaire on children's performance in activities of daily living. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014; 35(7): 1711-9

- ↑ Henderson S, Sugden D, Barnett A. Movement assessment battery for children-2 (MABC-2), 2nd edn. The Psychological Corporation. Harcourt Brace and Company Publishers. London; 2007

- ↑ Bruininks RH, Bruininks BD. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2). APA PsycTests. 2005

- ↑ Jírovec J, Musàlek M, Mess F. Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition (BOT-2): Compatibility of the Complete and Short Form and Its Usefulness for Middle-Age School Children. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2019; 7: 2296-2360

- ↑ World Health Organisation (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health, available: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ [accessed 1 April 2012]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rivilis, I., Hay, J., Cairney, J., Klentrous, P., Liu, J. and Faught, B.E. (2011) ‘Physical activity and fitness in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review’, Research in developmental Disabilities, 32(3), 894-910, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 8 Mar 2012]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hands, B. and Larkin, D. (2002) ‘Physical fitness and developmental coordination disorder’, in Cermack, S.A. and Larkin, D., eds., Developmental Coordination Disorder, New York: Delmar Thomson Learning, 172-185

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Farhat F, Denysschien M, Mezghani N, Kammoun MM, Gharbi A, Rebai H, Moalla W, Smits-Engelsman B. Activities of daily living, self-efficacy and motor skill related fitness and the interrelation in children with moderate and severe Developmental Coordination Disorder. PLos ONE. 2024; 19(4): e0299646

- ↑ Green, D., Lingam, R., Mattocks, C., Riddoch, C., Ness, A. and Emond, A. (2011) ‘The risk of reduced physical activity in children with probable developmental coordination disorder: a prospective longitudinal study’, Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1332-1342, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 5 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Dockrell, J., Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G. (2000) ‘Researching children’s perspectives: a psychological dimension’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching Children’s Perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 46-58

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 Jarus, T., Lourie-Gelberg, Y., Engel-Yeger, B. and Bart, O. (2011) ‘Participation patterns in school-aged children with and without DCD’, Research in developmental disabilities, 32(4), 1323-1331, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 20 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Magalhaes, L.C., Cardoso, A.A. and Missiuna, C. (2011) ‘Activities and participation in children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review’, Research in developmental disabilities,32(4), 1309-1316, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 8 Mar 2011]

- ↑ Lloyd-Smith, M. and Tarr, J. (2000) ‘Researching children’s perspectives: a sociological dimension’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching Children’s Perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 59-70

- ↑ Pollock, N. and Stewart, D. (1998) ‘Occupational performance needs of school-aged children with physical disabilities in the community’, Physical and occupational therapy in pediatrics, 18(1), 55-68, available: Informa Healthcare [accessed 20 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Winn-Oakley, M. (2000) ‘Children and young people and care proceedings’, in Lewis, A. and Lindsay, G., eds., Researching children’s perspectives, Philadelphia: Open University Press, 73-85

- ↑ Smits-Engelsman BCM. Developing a motor PERFormance and physical FITness test battery for low resourced communities (2nd ed.). Cape Town: PERF-FITT

- ↑ Smits-Engelsman B, Bonney E, Neto JLC, Jelsma DL. Feasibility and content validity of the PERF-FIT test battery to assess movement skills, agility and power among children in low-resource settings. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1): 1-11

- ↑ Smits-Engelsman B, Smit E, Doe-Asinyo RX, Lawerteh SE, Aertssen W, Ferguson G. Inter-rater reliability and test-retest reliability of the Performance and Fitness (PERF-FIT) test battery for children: a test for motor skill related fitness. BMC Pediatrics. 2021; 21(1): 1-11

- ↑ Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, Rodriguez MC, King-Dowling S, Kwan MY, Wade T. Cohort profile: the Canadian coordination and activity tracking in children (CATCH) longitudinal cohort. BMJ open. 2019; 9(9): e029784

- ↑ Doe-Asinyo RX, Smits-Engelsman BC. Ecological validity of the PERF-FIT: Correlates of active play, motor performance and motor skill-related physical fitness. Heliyon. 2021; 7(8): 34504965

- ↑ Mercê C, Cordeìro J, Romão C, Caloço Branco MA, Catela D. Deficits in Physical Activity Behaviour in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. 2023; 47: 1988-2041

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 31.9 Cairney, J., Hay, J.A., Faught, B.E., Wade, T.J., Corna, L. and Flours, A. (2005a) ‘Developmental coordination disorder, generalized self-efficacy toward physical activity, and participation in organized and free play activities’, The journal of paediatrics, 147(4), 515-520, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 6 Mar 2012]

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Fong, S.S.M., Lee, V.Y.L., Chan, N.N.C., Chan, R.S.H., Chak, W. and Pang, M.Y.C. (2011) ‘Motor ability and weight status are determinants of out-of-school activity participation for children with developmental coordination disorder’, Research in developmental disabilities,32(6), available: ScienceDirect [accessed 5 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Engel-Yeger, B. and Hanna Kasis (2010) ‘The relationship between developmental coordination disorder, child’s perceived self-efficacy and preference to participate in daily activities’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(5), 670-677, available: Wiley Online Library [accessed 5 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Braaksma P, Stuive I, Eibrink JW, Snoeren L, Postuma EMJL, Dekker R, van der Sluis CK, Schoemaker MM. Participation in recreational and leisure activities of 4-12-year-old children with developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review. University of Groningen. 2020

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Poulsen, A.A., Ziviani, J.M., Johnson, H. and Cuskelly, M. (2008a) ‘Loneliness and life satisfaction of boys with developmental coordination disorder: the impact of leisure participation and perceived freedom in leisure’, Human movement science, 27(2), 325-343, available: ScienceDirect [accessed 6 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Anderson, C.P., Hagstromer, M. and Yngve, A. (2005) ‘Validation of the PDPAR as an adolescent diary: Effect of accelerometer cut points’, Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 37(7), 1224-1230, available: OvidSP [accessed 6 Mar 2012]

- ↑ King, G., Law, M., King, S., Hurley, P., Hanna, S., Kertoy, M. and Rosenbaum, P. (2007) ‘Measuring children’s participation in recreational and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(1), 28-39, available: CINAHL

- ↑ Mattocks, C., Ness, A., Deere, K., Leary, S., Tilling, K., Blair, S.N. and Riddoch, C. (2008) ‘Early determinants of physical activity in 11 to 12 year olds: cohort study’, British Medical Journal, 336(7634), 26-29, available: JSTOR

- ↑ Cavalcante Neto JL, Draghi TTG, Santos IWP, Brito R, Da S, Silva LS, de O, Lima US. Physical Fitness in Children With Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Systematic Review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2024; 1-30

- ↑ Wall, A.E. (2004) ‘The development of skill learning gap hypothesis: implications for children with movement difficulties’, Adapted physical activity quarterly, 21(3), 197-218, available: SPORTDiscus

- ↑ King-Dowling S, Kwan MYW, Rodriguez C, Missiuna C, Timmons BW, Cairney J. Physical activity in young children at risk for developmental coordination disorder. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2019; 61: 1302-1308

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Missiuna, C., Moll, S., King, G., Stewart, D. and MacDonald, K. (2008) ‘Life experiences of young adults who have coordination difficulties’, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(3), 157-166

- ↑ Chase, M.A. and Dummer, G.M. (1992) ‘The role of sports as a social status determinant for children’, Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 63(4), 418-424

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Engel-Yeger, B. and Hanna Kasis (2010) ‘The relationship between developmental coordination disorder, child’s perceived self-efficacy and preference to participate in daily activities’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(5), 670-677, available: Wiley Online Library

- ↑ Le T, Graham JD, King-Dowling S, Cariney J. Perceptions of ability mediate the effect of motor coordination on aerobic and musculoskeletal exercise performance in young children at risk for Developmental Coordination Disorder. Journal of Sports and Exercise Psychology. 2020; 42(5): 407-16

- ↑ Li Y-C, Kwan MY, King-Dowling S, Rodriguez MC, Cariney J. Does physical activity and BMI mediate the association between DCD and internalizing problems in early childhood? A partial test of the Environmental Stress Hypothesis. Human Movement Science. 2021; 75: 102744

- ↑ Wrotniak, B.H., Epstein, L.H., Dorn, J.M., Jones, K.E. and Kondilis, V.A. (2006) ‘The relationship between motor proficiency and physical activity in children’, Pediatrics, 118, (6), 1758-1765

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Fitzpatrick, D.A. and Watkinson, E.J. (2003) ‘The lived experience of physical awkwardness: adults’ retrospective views’, Adapted physical activity quarterly, 20(3), 279-297, available: SPORTDiscus [accessed 6 Mar 2012]

- ↑ Kim, S.Y. and Wong, V.Y. (2002) ‘Assessing Asian and Asian American parenting: A review of the literature’, in Kurasaki, K., Okazaki, S. and Sue, S., eds., Asian American mental health: Assessment methods and theory, Netherlands; Kluwer Academic Publishers, 185-203

- ↑ Noordstar JJ, Volman M. Self-perceptions in children with probable developmental coordination disorder with and without overweight. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2020; 99; 103601

- ↑ Nobre G, Valentini N, Ramalho M, Sartori R. Self-efficacy profile in daily activities: Children at risk and with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics & Neonatology. 2019; 60(6): 662-8

- ↑ Harter, S. and Pike, R. (1984) ‘The pictorial scales of perceived competence and social acceptance for young children’, Child development, 55(6), 1969-1982, available: