Uterine Prolapse

Original Editors - Amanda Mattingly from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Uterine prolapse is the condition of the uterus collapsing, falling down, or downward displacement of the uterus with relation to the vagina.[1] It is also defined as the bulging of the uterus into the vagina.[2]

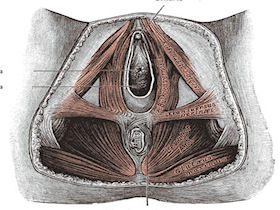

When in proper alignment, the uterus and the adjacent structures are suspended in the proper position by the uterosacral, round, broad, and cardinal ligaments. The musculature of the pelvic floor forms a sling-like structure that supports the uterus, vagina, urinary bladder, and rectum.[2] Uterine prolapse is a result of pelvic floor relaxation or structural overstretching of the muscles of the pelvic wall and ligamentous structures.

Uterine prolapse is characterized under a more general classification called pelvic organ prolapse which encompasses descent of the anterior, middle and posterior structures into the vagina.[3]

- Those organs that bulge anterior into the vagina are the urinary bladder which is called a cystocele, the urethra which is called a urthrocele or a combination which is a cystourethrocele.[2],[3]

- The uterus and the vaginal vault, which is the apex of the vagina that can prolapse after a hysterectomy, make up the organs that constitute the middle portion descent into the vagina.[3]

- The rectal buldge is called a rectocele and a bulge of part of the intestine and peritoneum are called a enterocele, these make up the posterior portion of pelvic organ prolapse.[2],[3] The information from this point forward will focus on uterine prolapse.

Uterine prolapse is classified using a four part grading system:

Grade 1: Descent of the uterus to above the hymen

Grade 2: Descent of the uterus to the hymen

Grade 3: Descent of the uterus beyond the hymen\

Grade 4: Total prolapse.[3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Each source presents with a differing prevalence depending on the researcher and the population used. One study stated that the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse, a clinical classification for all of the pelvic structures prolapse into the vagina, was 50% for women who have give birth, though most women are asymptomotic.[3] Another article cited that 50% of the female population in the United States are affected by pelvic order prolapse with a prevalence rate that can vary from 30% to 93% varying among different populations.[4] A questionnaire based study stated that 46.8% of the responses were positive to signs of pelvic organ prolapse and of the response group, 46.9% were vaginally examined with 21% having clinically relevant pelvic organ prolapse.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The primary symptoms of a uterine prolapse are backache, perineal pain, and a sense of "heaviness" in the vaginal area.[2] Pain associated with uterine prolapse can be located centrally, suprapubic, and dragging in the groin. This pain is due to stretching of the ligamentous supports and secondarily to abrasion of the prolapsed tissues.[1] If the prolapse has progressed into a grade three or third degree prolapse, the person may feel as though they have a lump at the vaginal opening and have irritation and abrasion of the exposed mucous membrane of the cervix and vagina. This is possible both during sexual intercourse and from wiping with toileting procedures. The person may report that the symptoms are relieved by lying down and exacerbated with prolonged standing, walking, coughing or straining. An associated complication of uterine prolapse is urinary incontienice.[2] Summary from Differnetial

Diagnosis for Physical Therapists:

- Lump in vaginal opening

- Pelvic discomfort, backache

- Abdominal cramping

- Symptoms relieved by lying down

- Symptoms made worse by prolonged standing, walking, coughing, or straining

- Urinary incontinence

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Obesity is a co-morbidity that often leads to progression and complication with uterine prolapse. In a study by the NIH, over a five year period 55.7% of the women in the study gained weight and the rate of prolapse increased from 40.9% to 43.8%. Looking specifically at uterine prolapse, when comparing participants with healthy BMI’s to overweight and obese persons, the risk of prolapse increased by 43% and 69% respectively. However, the loss of weight did not presuppose a reversal of the uterine prolapse.[4]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Hormone replacement therapy in the oral or vaginal form are indicated or a possible treatment to assist in maintaining elasticity of the pelvic floor musculature.[2][3]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Observation is often the first means of diagnosis.[2] Physical examination is the primary means for diagnosis. A bimanual test is performed with a speculum while the person is at rest and when the person is straining. If prolapse is not apparent with the first method, the person repeats the test while standing with one foot on a chair. The person is then graded using a first through third degree categorization. A first degree prolapse is characterized by descent of the uterus to above the hymen. A second degree prolapse is to the level of the hymen and a fourth degree prolapse is below the level of the hymen and protrudes through the vaginal opening.[2] Urine culture is ordered if a needed. If still unsure about the diagnosis, a pelvic ultrasonography or cystography can be ordered.[3]

Causes[edit | edit source]

Women most at risk for this condition are those who have had multiple pragnancies and deliveries in combination with obesity. Assosciated risk factors are trama to the pudendal or sacral nerves when giving birth. The disorder has been attributed to prlonged labor, bearing down before full, dialation, and forceful delivery of the palcenta. Decreased muslc tone due to aging, excessive strain during bowen movment and complications of pelvic surgery have also been associated with prolapse of the uterus and adjacent organs.[2] Associated risk also axists with pelvic tumors and neurologic condition like spina bifida and diabetic neuropathy which interfrers with innervation of pelvic musculature.[2]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

The digestive system can be impacted by uterine prolapse if the uterus obstructs the bladder/urethra and the rectum from voiding.[6] The reproductive system can also be impacted by painful intercourse, decreasing the ability for reproduction.[1]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Corrective surgery was a once popular first step but it has fallen second choice to rehabilitation. When surgery is indicated, it is a management tool for second and third-degree uterine prolapse.[2] Pelvic organ prolapse surgery has a success rate of 65% to 90% and has a repreated rate of operation at 30%. Patients who have more than one compartment involved may need a combination of surgeries and can often predispose patients ot prolapse in another compartment. Surgery can be both open or laproscopic of the abdomen or can be in the vagina using fasciae, mesh, tape or sutures to suspend the organs. Another surgical procedure that is used in attempt to conserve the uterus is a sacrohysteropexy which is a Y-shaped graft that attaches the uterus to the sacrum.[3] One case study that examined the effectiveness in laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy, stated that this procedure “maintains durable anatomic restoration, normal vaginal axis and sexual function.” It also requires less time and less adhesion formation due to laparospocia approach versus an abdominal route.[7] Vaginal hysterectomy, vesicourethral suspension, and abdominal hysterectomy are other possible approaches.[2] A pessary can be considered which is a shaped device made to support the uterus in the vagina. There is a supportive type for milder prolapse and a space-occupying type for more serious prolapse. The goal of the pessary is to find the largest fit that is comfortable. They are to be re moved regularly for cleaning by the individual with correct education or by a health care professional.[3]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Pelvic floor strengthening exercise is currently front line treatment before surgical option and also following surgery, these include but are not limited to Kegel exercises.[2][3] Other methods currently used are reeducation, postural education, biofeedback and electrical stimulation.[2]

Education on positions of irritation and management of pain during exercise program and during sexual intercourse with gravity assisted positions. Supine with a pillow or wedge support under the pelvis can be useful position for rest, pelvic floor exercise performance and during intercourse.[1]

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Methods considered in association to pelvic floor muscle strengthening are weight loss for preventative measures, smoking cessation and treatment of constipation.[3] Other suggestions from another source suggest adequate hydration, fiber intake, developing regular bowel habits, regular exercise, and hormone replacement therapy.[2]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

add text here

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

add appropriate resources here

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1BOJ2J2KKlLDU4InWGbRCc7YMJP63DBKmJ-usz8oZ6308F1UdI!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2007.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2009

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Bordman R, Telner D, Jackson B, Little D. Step-by-step approach to managing pelvic organ prolapse. Canadian Family Physician; 2007; 53: 485-487.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kudish BI, Iglesia CB, Sokol RJ, Cochrane B, Richter HE, Larson J, et al. Effect of weight change on natural history of pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 81-88.

- ↑ Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJC, Steegers-Theunissen RPM, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. Prediction model and prognositc index to estimate clinically relevant pelvic organ prolapse ina general female population. Int Urogynecol J 2009; 20: 1013-1021.

- ↑ Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard Al, Eijkemans MJC, Steegers-Theunissen RPM, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse symptoms and signs and their relation with bladder and bowel disorders in a general female population. Int Urogynecol J 2009; 20:1037-1045.

- ↑ Faraj R, Broome J. Laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy and myomectomy for uterine prolapse: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2009; 3: 99-102.