Hip Dysplasia

Original Editor Ruben Van Laere

Top Contributors - Samuel Adedigba, Lucinda hampton, Lauren Heydenrych, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Laura Ritchie, Sai Kripa, Admin, Ruben Van Laere, Ewa Jaraczewska, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Oyemi Sillo and Rucha Gadgil

Definition[edit | edit source]

Developmental dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) also known as a congenital hip dislocation is a general term used to describe certain abnormalities of the femur, or the acetabulum, or both, nearly always diagnosed within the first two years of life, that results in inadequate containment of the femoral head within the acetabulum, resulting in an increased risk for joint dislocation, dislocatability, or inadequate joint development. In the joint the articulating bones are displaced which leads to separation of the joint surfaces.

There are two types of dislocation: typical and teratological. DDH occurs in approximately 1 in 1000 live births. The dislocation is more common in girls and the left hip is more affected than the right. There is also a chance that the dislocation is bilateral. [1][2][3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

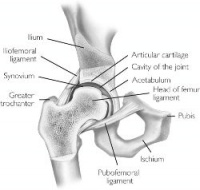

The Hip joint is a classical ball-and-socket joint. It meets the four characteristics of a synovial or diarthrodial joint: it has a joint cavity, joint surfaces are covered with articular cartilage, it has a synovial membrane producing synovial fluid, and it is surrounded by a ligamentous capsule.[4]

Embryologically, the femoral head and acetabulum develop from the same block of mesenchymal cells. A cleft develops after 7 to 8 weeks and will separate the femoral head from the acetabulum. Postnatally, the acetabulum will develop and there will be a growth of the labrum which will deepen the socket. A deep concentric position of the femoral head in the acetabulum is necessary for a normal development of the hip. When the bone structures of the hip are fully grown, we can speak of a ball and socket joint between the rounded head of the femur and the cup-like acetabulum of the femur.[5]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are several causes of DDH. First of all, there is the genetically determined joint laxity. This means that ligamentous laxity leads to lack of stability at the hip so that dislocation may easily occur in certain positions of the hip. It is possible that in females a ligament relaxing hormone may be secreted by the foetal uterus. This may cause instability in the same way as genetically determined joint laxity. This is probably the reason while this disorder occurs more commonly in girls than in boys.

Hip Dysplasia can also be caused by a lot of structural abnormalities like a shallow acetabulum, a flat or irregular caput femoris, a femoral or acetabular anteversion, and a decreased head offset or perpendicular distance from the center of the femoral head to the axis of the femoral shaft. Another risk factor is swaddling the infant and the use of cradle board which locks the hip joint in an "abducted" position for extended periods.

Other risk factors are firstborn and breech birth. In breech position, the caput femoris tends to be pushed out of the acetabulum. A narrow uterus also facilitates hip joint dislocation during fetal development and birth.

Finally genetically determined dysplasia of the hip can occur. This is created by a genetic factor which runs in the family or which is increased in certain ethnic populations (Native Americans and Sami people). Some studies suggest it has something to do with the hormone relaxine and others suggest it has something to do with chromosone 13. Due to a defect in the development of the acetabulum and also of the femoral head a dislocation can be developed.[1][2] Conditions can also be bilateral or unilateral. With bilateral dysplasia both hips are affected. With unilateral dysplasia only one hip is affected.

Characteristics/ Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

A hip is unstable when the femoral head is able to move within (subluxated) or outside (dislocated) the confines of the acetabulum.[3]

Hip dysplasia will occur during the development of the hip. This means prenatal, during infancy and childhood. In this case the femoral head will be dislocated upwards and laterally from the acetabulum. This is because femoral head is not reduced into the depth of the socket. The femoral neck will be anteverted and the ossific centre for the roof of the acetabulum will develop late. Because of this process the surrounding muscles become contracted and there will be a limited abduction of the hip.[1][2]

Hip dysplasia can be recognized by legs of different length, uneven skin folds on the thigh or asymmetric gluteus folds, Less mobility or flexibility on one side limping, toe walking, or a waddling, duck-like gait.

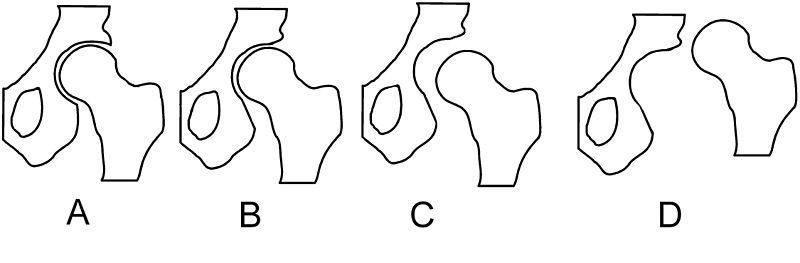

In 1979, Dr. John F. Crowe et al created a classification to define the degree of malformation and dislocation.[6] This classification evaluates the amount of femoral head subluxation in relation to the acetabular height. The classification has 4 degrees from less severe(1) to severe(4).

| Class | Description | Dislocation |

|---|---|---|

| Crowe I | Femur and acetabulum show minimal abnormal development | Less than 50% dislocation |

| Crowe II | The acetabulum shows abnormal development | 50% to 75% dislocation |

| Crowe III | The acetabula is developed without a roof. A false acetabulum develops opposite the dislocated femur head position. The joint is fully dislocated | 75% to 100% dislocation |

| Crowe IV | The acetabulum is insufficiently developed. Since the femur is positioned high up on the pelvis this class is also known as "high hip dislocation" | 100% dislocation |

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Pain in the hip region can also be caused by:

- Hip joint contusion,

- Strain,

- Athletis pubalgia,

- Osteitis pubis,

- Inflammatory arthritis,

- Osteoarthritis,

- Septic arthritis,

- Piriformis syndrome,

- Snapping hip syndrome,

- Bursitis,

- Femoral head avascular necrosis,

- Fracture,

- Dislocation,

- Tumor,

- Hernia,

- Slipped femoral capital epiphysis,

- Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, or

- Referred pain from the lumbosacral and sacroiliac areas.

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

| [7] |

It is important to examine DDH in an early stage. This is not easy because of the lack of a definitive test or finding on examination. The disorder is also painless so there are no symptoms in the infant. Particularly bilateral dislocations are difficult to detect.

All newborns are to be screened by physical examination. This examination includes an Ortolani or Barlow test. If the tests are positive, the infant should be referred to an orthopedist.

If the test is negative, but no asymmetric skin folds were detected or if the subluxation provocation test is positive, it is recommended that there is a follow up after two weeks by a pediatrician. When he then finds a positive Ortolani test or Barlow test, it is recommended to send the newborn to an orthopedist. If these tests are negative but the provocation test is positive, an ultrasonography is recommended. In most cases, an ultrasonography will provide clarity about the disorder, but it is not recommended to carry out such a test for all newborn.[5][8][9]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

| [10] |

We need to make a difference between the neonatal cases and the cases where the disorder is examined between 6 months and 6 years. In the case where the dislocation is found on neonatal screening we need to wait 3 weeks to intervene. Sometimes the hip becomes stable spontaneously. In this case it is still important that the child is reexamined at the age of 5 or 6 months. If on the other hand the hip is still unstable after three weeks, splinting in the reduced position in moderate abduction is recommended for a minimum of six weeks or for as long as instability persists. When splinting is needed for a longer period, the risk will increase for the development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

Between six months and six years there are three essential principles of treatment. First of all to secure the concentric reduction, secondly to provide conditions favorable to continued stability and normal development and thirdly to observe the hips regularly in order to detect any failure of normal development of the acetabulum and to apply appropriate treatment when necessary.

If possible, it is important to obtain reduction by non-operative means. Surgery is performed when other methods fail.

Closed reduction is often possible in babies up to eighteen months old. When DDH is diagnosed later the chances increase that an operation is needed. Closed reduction is the standard practice and will apply weight traction to the limbs with the child either on a frame or in gallows suspension. While traction is maintained gradually to abduct the hips, a little more each day, until 80 degrees of abduction is reached. This will take three to four weeks.[11][1][2][12]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The traditional physical therapy includes ball catching, ball bouncing, target throwing, kicking, balance beam activities, gait and stairs and unleveled terrain, running and jumping as well as sensory integration activities including swiss ball, vestibular swing tasks and scooter board.

In addition, there is another therapy called hippotherapy. The protocol for hippotherapy includes riding a forward, backward, and side saddle position while the horse walked in a four beat gait moving in a serpentine and figure eight patterns. Ball throwing and catching on the horse while stationary as well as ring tossing and placing. The session ends with the horse trotting while the subject faced forward working on advanced balance and core control.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 John Crawford Adams, David L. Hamblem, Outline of Orthopaedics, Churcill Livingstone, 1995, twelfth edition, p. 292 – 301.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 John Crawford Adams, David L. Hamblem, Outline of Orthopaedics, Churcill Livingstone, 2001, thirteenth edition, p. 305 – 312.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hema Patel, with the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, Preventive Health care, 2001 update: screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns, Cmaj, June 12, 2001; 164 (12), p. 1669 -1677.

- ↑ Byrd J. Gross anatomy. In: Byrd J, editor. Operative Hip Arthroscopy. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, Inc; 2004.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 . American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip, Clinical Practice Guideline : Early detection of developmental Dysplasia of the hip, Offical Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics Vol 105 No 4 April 2000, downloaded from pediatrics. Applications.org at Swets Blackwell 30680247 on November 23, 2011.fckLR Level of evidence: 1 A

- ↑ Crowe JF, Mani VJ, Ranawat CS. Total hip replacement in congenital dislocation and dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979 Jan 1;61(1):15-23.

- ↑ 1orthojpmc. Ortolani's Click & Barlow's Maneuver . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mv_kLqZSGdo [last accessed 04/05/13]

- ↑ Andreas Roposch, Liang Q. Liu, Fritz Hefti, M. P. Clarke, John H. Wedge, Standardized Diagnostic Criteria for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Early Infancy, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (2011) 469:3451 – 3461.fckLR Level of evidence: 1 B

- ↑ Harry B. Skinner, Current : Diagnosis and treatment in Orthopedics, McGraw Hill Medical Publishing Division, 2000, second edition, p.1537 – 1540.

- ↑ ChildrensHospital. Angela and hip dysplasia - Boston Children's Hospital. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bShtxYFdERQ [last accessed 04/05/13]

- ↑ Christian Tschauner, Frank Fürntrath, Yasaman Saba, Andrea Berghold, Roman Radl, Developmental dysplasia of the hip : impact of sonographic newborn hip screening on the outcome of early treated decentered hip joints – a single center retrospective comparative cohort study based on Graf’s method of hip ultrasonography; J. Child Orthop (2011) 5:415-424.fckLR Level of evidence: 1 B

- ↑ Lawrence W. Way, Current : Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment, Prentice Hall International, 1994, tenth edition, p. 1085 – 1087.