Diastasis Recti Abdominis

Original Editor - Marianne Ryan

Top Contributors - Nicole Hills, Sivapriya Ramakrishnan, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Victoria Geropoulos, Regan Haley, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Marianne Ryan, Oyemi Sillo, Kim Jackson, Michelle Walsh, WikiSysop, Tarina van der Stockt and Claire Knott

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Diastasis recti abdominis is a separation of the rectus abdominal muscles at the linea alba.[2] Diastasis recti abdominis can occur as a result of prolonged transverse stress on the linea alba in men,[3] postmenopausal women,[4] and in women during pregnancy. [5][6] It can also occur in newborns and is defined as an inter-rectus distance that is greater than 3cm in this population.[7]

Diastasis Recti Abdominis and Pregnancy[edit | edit source]

During pregnancy the linea alba softens due to hormones and the mechanical stretch resulting from the accommodation of the growing fetus.[8] Because of this, there will be a progressive increase in the width of the linea alba (the inter-rectus distance or IRD) throughout the trimesters, with the highest incidence occurring in the third trimester.[8]

A recent study by da Mota and colleagues[9] included 84 first-time pregnant women and found that 100% of them had DRA by gestational week 35 when using a diagnostic criterion of 1.6cm at 2cm below the umbilicus. The prevalence decreased to 52.4% at 4-6 weeks postpartum and continued to decrease to 39% at 6 months.[9] While this agrees with other studies that have also found a decreased prevalence at 4 weeks[2][10] and 8 weeks postpartum,[8] a study by Coldron and colleagues[11] found that healing reached a plateau at 8 weeks postpartum and that IRD and rectus abdominis thickness and width did not return to the control values one year later.

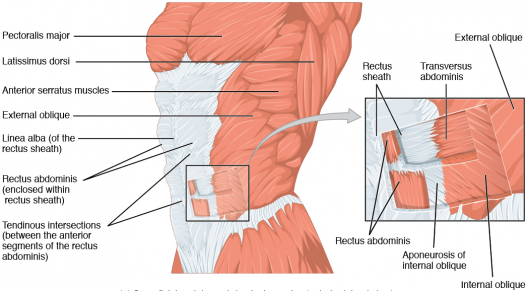

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The two rectus abdominis muscle heads run parallel to each other and are separated by a connective tissue along the midline of the body called the linea alba.[12] The distance between the rectus abdominis muscles is referred to as the inter-rectus distance.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

An adult is considered to have diastasis recti abdominis when they present with an increased inter-rectus distance (IRD) from normal value, characterized by an observable and palpable separation between the two bellies of the rectus abdominis muscle.[13]

Currently, there is no consensus among the literature regarding the measurement criteria and diagnostic IRD cut-off value for DRA.[14] A study by Beer and colleagues suggests that, in nulliparous women (women who have not given birth), the normal width of the linea alba should be less than 1.5 cm at the xiphoid level, less than 2.2 cm at 3 cm above the umbilicus, and less than 1.6 cm at 2 cm below the umbilicus.[15]

However, when applying these values to clinical practice it is important to consider that the IRD values observed in primiparous women (or women who have given birth for the first time) may be seen as “normal” at wider values than nulliparous women.[16] A more recent study by Mota and colleagues suggests that the linea alba is considered normal up to 2.1 cm at 2 cm below the umbilicus, to 2.8 cm at 2 cm above the umbilicus and to 2.4 cm at 5 cm above the umbilicus at 6 months post-partum in primiparous women.[16]

To gain a more comprehensive understanding during physical assessment, a consensus study by Dufour and colleagues suggests that IRD should not be the only measure assessed when diagnosing DRA.[17] Clinicians should assess the anatomical and functional characteristics of the linea alba.[17] This includes palpating for tension during active contraction of linea alba[17], as well as during co-contraction of the pelvic floor muscles and the transverse abdominis.[18] As well, since larger IRDs are correlated with poorer trunk control[19], strength and endurance of the abdominal muscles should also be considered during assessment.[17]

Diagnostic Methods[edit | edit source]

The most traditionally used diagnostic method in clinical practice is the finger – width method, which primarily functions as a screening tool.[21] This tool is used to detect the presence or absence of DRA. If on palpation, the therapist can place two or more finger breaths (≈2cm) in the sulcus between the medial borders of the rectus abdominis muscles, the patient may present with diastasis recti abdominis.[22]

In terms of measuring IRD, ultrasound imaging (USI) has been titled the gold-standard method to measure IRD non-invasively[23], displaying good inter-rater [13] and intra-rater reliability in the literature. [16] However, its daily clinical use may be limited due to cost, availability, and training.[21] A more clinically feasible alternative is the use of calipers, whereby the tips of calipers are fitted across the width of the separation.[21] Calipers are considered to be reliable tool for measures of IRD at and above the umbilicus.[21] This was supported by Chiarello and McAuley, who found that IRD measures with calipers were similar to those taken with USI above the umbilicus[24], however, additional research is need to evaluate the potential of calipers relative to ultrasound imaging.[21]Other alternatives include computed tomography (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which are considered the method of choice when assessing the abdominal wall, however both are not clinically feasible and are expensive.[21]

Role for PT Management[edit | edit source]

Our abdominal muscles play an important role in postural control, trunk and pelvic stability, trunk movement and respiration.[25] A study by Gilleard and Brown previously reported that the structural changes that occur to the abdominal muscles during pregnancy can limit abdominal muscle function, decreasing the ability of the abdominals to provide stability to the pelvis against resistance during pregnancy and up to 8 weeks postpartum.[2] In support of this, a study by Liaw and colleagues suggested that the size of IRD was negatively associated with abdominal muscle function.[26] Additionally, a more recent study by Hills and colleagues determined that women with DRA had a lower capacity to generate trunk rotation torque and perform sit-ups.[19] This was supported by a negative correlation between IRD and trunk rotation peak torque generating capacity and sit-up test scores.[19]

Some studies have implicated weak abdominal muscles in causing abdominal (Fast el.,1990) and lumbo-pelvic pain and dysfunction during pregnancy (Parker et al., 2008 and Spitznagle et al., 2007). There is some evidence to support the idea that an increased inter-rectus distance is associated with the severity of self-reported abdominal pain (Keshwani et al., 2017). Additionally, it has also been hypothesized that weak abdominal muscles can result in ineffective pelvic floor muscle (PFM) contraction (Spitznagle et al., 2006).

However, evidence doesn’t fully support this as da Mota and colleagues[9] and Sperstad and colleagues[27] found no link between DRA and lumbopelvic pain. Bø and colleagues[28] also found no link between DRA and weakness of pelvic floor musculature or prevalence of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

While the condition is very common, there is a lack of high-quality evidence to guide management in clinical practice. This creates debate when it comes to carrying out a conservative care approach. [17] However, Dufour and colleagues[17] interviewed credentialed women’s health physiotherapists to create 28 Canadian expert-based recommendations, which were further categorized into primary and secondary importance.

Beginning exercises prenatally may help to maintain the tone and control over abdominal musculature to decrease some stress of the linea alba.[29] Early literature suggests that functional capacity of abdominal musculature may be compromised due to a change in the muscle’s line of action.[2] Since then, Chiarello and colleagues[30] found that the occurrence and size of DRA is greater in pregnant women who do not exercise and that, since the abdominals play an important functional role in exercise, women must be screened for the presence of DRA. More recent evidence supports deep core stability-strengthening 3 times a week for 8 weeks, in addition to bracing, to improve inter-recti separation and quality of life as measured by the Physical Functioning Scale (PF10).[31] The exercises included diaphragmatic breathing, pelvic floor contraction, plank, isometric abdominal contractions, and traditional abdominal exercises.[31] Lee and Hodges[18] proposed that narrowing the IRD may not be optimal and that pre-activation of TrA can increase the tension and decrease the distortion of the linea alba, which will allow for force to be transmitted across the midline.

However, Gluppe and colleagues[32] found that a supervised exercise class once a week for 16 weeks, in addition to daily home training, did not reduce the prevalence of DRA at 6 months postpartum. The exercises focused on strengthening the pelvic floor, but also relaxation and stretching, as well as strengthening of the abdominals, back, arms, and thighs.[32]

Patient Education[edit | edit source]

It is important to educate our patients on diastasis recti abdominis during and after pregnancy. The video below by a Canadian physiotherapist uses a great analogy to explain the concept of diastasis recti abdominis.

Common Postpartum Exercises[edit | edit source]

Kegel Exercises[edit | edit source]

Pelvic floor exercises can help strengthen deep abdominal muscles. These exercises can be performed throughout pregnancy and may be started in the early postpartum period.

Breathing Exercises[edit | edit source]

Breathing exercises help to retrain the diaphragm to relearn how to descend after childbirth. During pregnancy, the diaphragm is pushed upwards by the growing uterus and loses its ability to descend during inhalation. Since the diaphragm forms the top of the core muscles, it is important to retrain it to function with a full excursion again. Here are 2 good exercises

- Inverted Breathing - Lie supine with the buttock on a pillow wedge, raised above chest level. Teach the patient to take short, shallow breaths “through the pelvic diaphragm.” Have the patient place one hand just above the pubic symphysis and teach them to feel for a slight up and down motion while they breathe in and out. Place the patient's other hand on top of their chest and tell them to try not to have their chest rise when breathing.

- Lateral Costal Breathing - In the seated position have the patient place their hands on the lateral sides of the rib cage. Teach them to “breathe into their hands” and to feel for the lateral expansion of the rib cage as they inhale and the movement of the ribcage toward the midline during exhalation.

Progressive Core Exercises[edit | edit source]

There are several exercises that can be used to help restore core strength after pregnancy. For more information refer to Diane Lee’s work on the Diastasis Recti.

Body Mechanics[edit | edit source]

It is important to teach the patient how to perform ADL’s without increasing abdominal pressure, such as rolling out of bed, instead of doing a “sit-up” to get up. Avoid “jack-knifing” behaviour that increases intra-abdominal pressure. Teaching patients to roll to their left side and use their top arm to help push themselves up is a commonly prescribed technique. Other activities to watch out for is getting out of a bath, lifting and carrying older children and heavy objects during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. Teach them to “exhale as you lift.”

Postural Awareness[edit | edit source]

After pregnancy, some women tend to stand with and an exaggerated anterior pelvic tilt and with their pelvis pushed forward. In order to stand up against gravity, their bodies typically develop areas of rigidity in the upper lumbar and the lower thoracic area along with the buttock muscles. Diane Lee refers to this as “back clenching and buttock griping behaviour.” Manual therapy and relaxation exercises may be indicated before initiating strengthening exercises. (http://dianelee.ca/articles/UnderstandYourBack&PGPopt.pdf)

Abdominal Supports[edit | edit source]

Abdominal Binders: Binders may be helpful for some women in the postpartum period, but the wrong or overuse of them can cause more problems. It is best not to use an abdominal binder unless necessary, for example during pregnancy in the third trimester and 6 weeks after delivery if there is a separation of 2 fingers or more.

Belly Band: Wearing a belly band during pregnancy (one made specifically for pregnant women) may help increase proprioception and muscle awareness. A belly band or tight tube top can be used after childbirth for the same reasons.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Wikimedia Commons.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1112_Muscles_of_the_Abdomen_Anterolateral.png (accessed 22 June 2018).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Gilleard WL, Brown JM. Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period. Physical therapy. 1996 Jul 1;76(7):750-62.

- ↑ Lockwood T. Rectus muscle diastasis in males: primary indication for endoscopically assisted abdominoplasty. Cosmetic. 1998;May:1685-1691.

- ↑ Spitznagle TM, Leong FC, Van Dillen LR. Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in a urogynecological patient population. International Urogynecology Journal. 2007 Mar 1;18(3):321-8.

- ↑ Akram J, Matzen SH. Rectus abdominis diastasis. Journal of plastic surgery and hand surgery. 2014 Jun 1;48(3):163-9.

- ↑ Brauman D. Diastasis recti: Clinical anatomy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008 Nov 1;122(5):1564-9.

- ↑ Marden PM, Smith DW, McDonald MJ. Congenital anomalies in the newborninfant, including minor variations: A study of 4,412 babies by surface examination for anomalies and buccal smear for sex chromatin. The Journal of pediatrics. 1964 Mar 1;64(3):357-71.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Boissonnault JS, Blaschak MJ. Incidence of diastasis recti abdominis during the childbearing year. Physical therapy. 1988 Jul 1;68(7):1082-6.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Mota PG, Pascoal AG, Carita AI, Bø K. Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Manual therapy. 2015 Feb 1;20(1):200-5.

- ↑ Hsia M, Jones S. Natural resolution of rectus abdominis diastasis. Two single case studies. Aust J Physiother. 2000 Jan 1;46(4):301-7.

- ↑ Coldron Y, Stokes MJ, Newham DJ, Cook K. Postpartum characteristics of rectus abdominis on ultrasound imaging. Manual therapy. 2008 Apr 1;13(2):112-21.

- ↑ Peterson-Kendall F, Kendall-McCreary E, Geise-Provance P, McIntyre-Rodgers, Romani W. Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain. 5th ed. Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer; 2005.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Keshwani N, Hills N, McLean L. Inter-rectus distance measurement using ultrasound imaging: does the rater matter?. Physiotherapy Canada. 2016;68(3):223-9.

- ↑ Mota P, Gil Pascoal A, Bo K. Diastasis recti abdominis in pregnancy and postpartum period. Risk factors, functional implications and resolution. Current Women's Health Reviews. 2015 Apr 1;11(1):59-67.

- ↑ Beer GM, Schuster A, Seifert B, Manestar M, Mihic‐Probst D, Weber SA. The normal width of the linea alba in nulliparous women. Clinical anatomy. 2009 Sep;22(6):706-11.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Mota P, Pascoal AG, Carita AI, Bø K. Normal width of the inter-recti distance in pregnant and postpartum primiparous women. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2018 Jun 1;35:34-7.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Dufour S, Bernard S, Murray-Davis B, Graham N. Establishing expert-based recommendations for the conservative management of pregnancy-related diastasis rectus abdominis: A Delphi consensus study. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2019 Apr 1;43(2):73-81.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lee D, Hodges PW. Behavior of the linea alba during a curl-up task in diastasis rectus abdominis: an observational study. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jul;46(7):580-9.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Hills NF, Graham RB, McLean L. Comparison of trunk muscle function between women with and without diastasis recti abdominis at 1 year postpartum. Physical therapy. 2018 Oct 1;98(10):891-901.

- ↑ Learn with Diane Lee. Linea alba screen DRA with Diane Lee. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06o8Z54l-40 [last accessed 22/06/2018]

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Van de Water AT, Benjamin DR. Measurement methods to assess diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM): a systematic review of their measurement properties and meta-analytic reliability generalisation. Manual therapy. 2016 Feb 1;21:41-53.

- ↑ Noble E. Essential Exercises for the Childbearing Year. 2nd edition. Boston, MA: Houghton Miffilin; 1982.

- ↑ Benjamin DR, Van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar 1;100(1):1-8.

- ↑ Chiarello CM, McAuley JA. Concurrent validity of calipers and ultrasound imaging to measure interrecti distance. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2013 Jul;43(7):495-503.

- ↑ Benjamin DR, Van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar 1;100(1):1-8.

- ↑ Liaw LJ, Hsu MJ, Liao CF, Liu MF, Hsu AT. The relationships between inter-recti distance measured by ultrasound imaging and abdominal muscle function in postpartum women: a 6-month follow-up study. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2011 Jun;41(6):435-43

- ↑ Sperstad JB, Tennfjord MK, Hilde G, Ellström-Engh M, Bø K. Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jun 20:bjsports-2016.

- ↑ Bø K, Hilde G, Tennfjord MK, Sperstad JB, Engh ME. Pelvic floor muscle function, pelvic floor dysfunction and diastasis recti abdominis: Prospective cohort study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2017 Mar 1;36(3):716-21.

- ↑ Zappile-Lucis M. Quality of life measurements and physical therapy management of a female diagnosed with diastasis recti abdominis. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2009 Apr 1;33(1):22.

- ↑ Chiarello CM, Falzone LA, McCaslin KE, Patel MN, Ulery KR. The effects of an exercise program on diastasis recti abdominis in pregnant women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2005 Apr 1;29(1):11-6.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Thabet AA, Alshehri MA. Efficacy of deep core stability exercise program in postpartum women with diastasis recti abdominis: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2019;19(1):62.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Gluppe SL, Hilde G, Tennfjord MK, Engh ME, Bø K. Effect of a postpartum training program on the prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in postpartum primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy. 2018 Apr 1;98(4):260-8.

- ↑ Phit Physiotherapy. DRA: Being (banana) split up the middle, a fresh (produce) perspective. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVxAUOkb3M4[last accessed 22/06/2018]

- ↑ Diane Lee's Integrated Systems Model for Physiotherapy in Womens' Health. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5oslM6Pe9AU&t=1844s [last accessed 22/6/2018]

- ↑ Diane Lee. Conference Presentations Diane Lee and Associates in Physiotherapy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHY6CSSosNE&t=10s[last accessed 22/6/2018]