William's Syndrome

Original Editors - Julie Frederick from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

William’s Syndrome, also known as Williams-Beuren Syndrome was first recognized as a unique disorder in 1961.[1] J.C.P. Williams observed in four patients an association between supravalvular stenosis and the common physical and mental characteristics of this patient population and stated that it “may constitute a previously unrecognized syndrome”[1]. Later, A.J. Beuren described eleven new patients with the characteristics described by Williams and the disorder became known as Williams-Beuren Syndrome.[1] Diagnosis of the syndrome can be made at birth based on physical characteristics, but a true medical diagnosis is confirmed following a diagnostic test called fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).[1] The test reveals a recurring micro-deletion, with a size of 1,551,83 Mb, on chromosome band 7q11.23, which contains 24-28 genes.[2][3][4] The deleted part of the chromosome band includes the elastin gene, which leads to serious cardiovascular complications.[5]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Stated as being anywhere from 1/7,500 to 1/50,000.[1][2][6][7] William’s Syndrome occurs sporadically and spontaneously and is found equally in all ethnicities, races, socioeconomic backgrounds and genders.[1][5][7]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

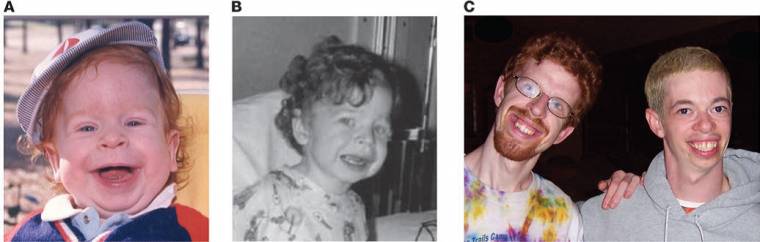

- Craniofacial dysmorphic features[1][2][3][4][5][7]

- Full lips[4][7], short nasal bridge[4], large forehead[4], long philthrum[7], epicanthal folds[7], hypertelorism[7], mandibular hypoplasia[7]

- Mild to moderate mental retardation[1][2][3][4][5][7]

- Average IQ = 55-60 but can range from 40-90[1]

- Mild to moderate learning disabilies2[2]

- Associated systemic disorders (especially cardiovascular)[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

- Mild growth retardation[1][3], short stature[5][7]

- Commonly overweight as adults[1]

- Deficient visuo-spatial abilities[3][4][5]

- Global processing deficits[4]

- Overfriendly personalities[2][3][5]

- Very sociable[4]

- Hyperacusis or algiacusis[3]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

According to Pober, Johnson and Urban, all of the following conditions have been associated with William’s Syndrome[1]:

Cardiovascular pathologies[2][3][4][5][6]

• Supravalvular aortic stenosis[4][6]

• Ventricular septal defect[6]

• Patent ductus arteriosus[6]

• Stenosis of outlying arteries (renal, cerebral, carotid, coronary, brachiocephalic, subclavian, mesenteric, lung)[6]

• Arteriovenous shunt[6]

• Interruption of the aortic arch[6]

• Vein aplasia[6]

• Aortic aneurysm[6]

• Pulmonary arterial stenosis[5]

• Left and right ventricular hypertrophy[5]

• Aortic coarctation[5]

• Mitral valve prolapse[5]

• Aortic valvular insufficiency[5]

Endocrine abnormalities[5]

• Hypercalcemia[4][6]

• Abnormal glucose metabolism

• Thyroid hypoplasia[7]

• Hypothyroidism[7]

Dental anomalies

• Small, abnormally shaped teeth

• Absent teeth

• Malocclusion

Gastrointestinal

• Dysmotility

• Reflux

• Constipation

• Diverticular disease

Musculoskeletal anomalies

• Joint stiffness

• Scoliosis

Sensorineural hearing loss

Genitourinay anomalies[5]

• Urinary frequency

• Bladder diverticuli

Neurological problems

• Abnormal tone

• Hyperreflexia

• Cerebellar dysfunction

Medications[edit | edit source]

There are no medications for William’s Syndrome itself, however, common medications for systemic complications may include: thyroxine for hypothyroidism[7]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

The most common test used to diagnose William’s Syndrome is fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).[1]

Other tests to diagnose systemic complications include: electrocardiogram, ultrasonography, Tc-pertechnetate thyroid scintigraphy, thyroid function tests,

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

add text here

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

add text here

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

add text here

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

Resources

[edit | edit source]

• William Syndrome Association: www.williams-syndrome.org

• Vanderbilt Kennedy Center: http://kc.vanderbilt.edu/site/about/default.aspx

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1fs6_IKzbbn66yo2UkGTwcbuiUpkdih7ZpBSc29eNkFUNGbE-M|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Pober B, Johnson M, Urban Z. Mechanisms and treatment of cardiovascular disease in Williams-Beuren syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation. (2008, May); 118(5): 1606-1615.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 John A, Mervis C. Comprehension of the Communicative Intent Behind Pointing and Gazing Gestures by Young Children with Williams Syndrome or Down Syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research. (2010, Aug); 53(4): 950-960.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Lucena J, Pezzi S, Aso E, Valero M, Carreiro C, Campuzano V, et al. Essential role of the N-terminal region of TFII-I in viability and behavior. BMC Medical Genetics. (2010, Apr 19); 1161.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Collette J, Xiao-Ning C, Mills D, Galaburda A, Reiss A, Korenberg J, et al. William's syndrome: gene expression is related to parental origin and regional coordinate control. Journal of Human Genetics. (2009, Apr); 54(4): 193-198.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 Del Pasqua A, Rinelli G, Toscano A, Iacobelli R, Digilio C, de Zorzi A, et al. New Findings concerning Cardiovascular Manifestations emerging from Long-term Follow-up of 150 patients with the Williams-Beuren-Beuren syndrome. Cardiology in the Young. (2009, Dec); 19(6): 563-567.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Figueroa J, Olivares Rodríguez L, Pablos Hach J, Ruíz V, Martínez H. Cardiovascular Spectrum in Williams-Beuren Syndrome. Texas Heart Institute Journal. (2008, Sep); 35(3): 279-285.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 Stagi, Manoni, Salti, Cecchi, Chiarelli. Thyroid Hypoplasia as a Cause of Congenital Hypothyroidism in Williams Syndrome. Hormone Research. (2008, Nov); 70(5): 316-318.