Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR) is a syndrome that develops prior to dementia. The syndrome consists of a slower gait, cognitive deficits and a is risk factor for various geriatric syndromes including frailty and falls.[1]

- New research is showing that gait dysfunction can be a forerunner of dementia.[2]

- MCR is an independent risk factor for both incident ADL and IADL disability, and confers a higher risk for disability than memory impairment.[3]

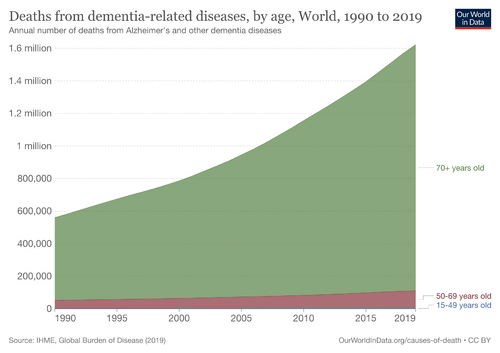

MCR amongst older persons is estimated to be 10% in the 60 + age group, giving this population a higher risk of future disability. As the global burden of dementia increases tools are needed to identify those vulnerable to dementia and instigate a preventative management plan.

Pathology[edit | edit source]

The pathology of MCR is due to frontal lacunar infarcts, for example:

- White matter hyperintensity (predicts an increased risk of stroke, dementia, and death[4]).

- Pre-motor and pre-frontal gray matter atrophy in the pre-motor and pre-frontal cortex

- Inflammatory changes

- Genetic factors.

Cerebrovascular lesions and cardiovascular disorders amplify the pathological changes. [5]

However the underlying pathogenesis of MCR remains poorly understood.[6]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Research has shown these group to be at risk of having the MCR syndrome:women; if you live in a rural areas; obesity; diabetes; heart disease; or having cancer.[7]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of MCR is an involved process comprising neuropsychological tests, biomarker assays (blood-based biomarkers potentially improve the accuracy by which specific causes of dementia can be diagnosed in vivo)[8], imaging studies, questionnaire-based evaluation, and motor function tests. [5]

Both neurological and non-neurological clinical abnormalities occur.

- Gait irregularities and accelerated functional decline (eg postural and balance dysfunction, memory loss, cognitive decline) stem from altered afferent sensory and efferent motor responses.

- Confusing visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive inputs. [5]

Management[edit | edit source]

Management of MCR is multimodal, including

- Lifestyle habits known to limit the disease progression. Similar to dementia recommendations. eg Cognitive, physical, and social activities

- Exercise

- Diet, nutritional supplements and vitamins known to support motor and cognitive improvement. eg vit D. A 2022 sudy showed identified that there is direct association between vitamin D deficeincy and MCR syndrome in older adults without dementia, and supplementation is advised.[1]

- Symptomatic drug treatment eg anti depressants

- Psychotherapeutic counselling[5]

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

See Physiotherapy for dementia- exercise is a great medicine for prevention, alongside other lifestyle habits.

Motor function tests for diagnosis and as treatment outcome measures include: including walking speed, dual-task gait tests, and ambulation ability.[5]

Exercise has been to shown to have a role in preventing cognitive decline. Home-based exercises (with telephonic coaching ideall;y) are both safe feasible treatment option for patients with Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome[9]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Le Floch M, Gautier J, Annweiler C. Vitamin D Concentration and Motoric Cognitive Risk in Older Adults: Results from the Gait and Alzheimer Interactions Tracking (GAIT) Cohort. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Oct 12;19(20):13086.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9602422/ (accessed 13.4.2023)

- ↑ Meiner Z, Ayers E, Verghese J. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: a risk factor for cognitive impairment and dementia in different populations. Annals of geriatric medicine and research. 2020 Mar;24(1):3.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7370775/(accessed 12.4.2023)

- ↑ Bai A, Bai W, Ju H, Xu W, Lin Z. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome as a predictor of incident disability: A 7 year follow-up study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2022 Sep 8.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9493455/ (accessed 13.4.2023)

- ↑ Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2010 Jul 26;341.Available:https://www.bmj.com/content/341/bmj.c3666 (accessed 13.4.2023)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Xiang K, Liu Y, Sun L. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: symptoms, pathology, diagnosis, and recovery. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2022 Feb 2;13:728799.Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8847709/ (accessed 12.4.2023)

- ↑ Semba RD, Tian Q, Carlson MC, Xue QL, Ferrucci L. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome: Integration of two early harbingers of dementia in older adults. Ageing research reviews. 2020 Mar 1;58:101022.Available:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31996326/ (accessed 13.4.2023)

- ↑ Lau H, Mat Ludin AF, Shahar S, Badrasawi M, Clark BC. Factors associated with motoric cognitive risk syndrome among low-income older adults in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2019 Jun;19:1-7.Available:https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-6869-z (accessed 13.4.2023)

- ↑ Ahmed RM, Paterson RW, Warren JD, Zetterberg H, O'brien JT, Fox NC, Halliday GM, Schott JM. Biomarkers in dementia: clinical utility and new directions. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2014 Dec 1;85(12):1426-34.Available:https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/85/12/1426(Accessed 13.4.2023)

- ↑ Ambrose AF, Gulley E, Verghese T, Verghese J. Home-based exercise program for older adults with Motoric Cognitive Risk syndrome: feasibility study. Neurodegenerative disease management. 2021 Jun;11(03):221-8.Available:https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/full/10.2217/nmt-2020-0064 (accessed 12.4.2023)