CBT Approach to Chronic Low Back Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

=== <br> Model of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy === | === <br> Model of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy === | ||

=== Bio-PsychoSocial Model === | === Bio-PsychoSocial Model === | ||

Revision as of 17:28, 13 January 2014

Original Editor - Alex Lamprell, Nick Holden, Sebastian Marriot, Kamal Manek as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Alex Lamprell, Sebastian Marriott, Kamal Manek, Alan Jit Ho Mak, Nick Holden, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Nina Myburg, Tarina van der Stockt, Admin, WikiSysop, Rishika Babburu, Evan Thomas and George Prudden

Introduction[edit | edit source]

This page is designed to outline and review existing literature on the different types of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). Additionally, literature comparing the different types of therapy has been analysed with relation to Physiotherapy.

Chronic Low Back Pain: Not Always Mechanical?[edit | edit source]

In recent years, Chronic Low Back Pain has been extensively researched to understand the confounding variables and barriers that effect people’s recovery rates. Throughout these years, an extensive amount of research has studied regarding the role of psychological issues in the development and maintenance or chronic low back pain (Grotle et al., 2004). Studies throughout these years have suggested that an increasingly negative orientation toward pain and fear of movement or re-injury are highly important in the aetiology of chronic low back pain (Susan et al., 2002). Therefore it has been suggested that a mechanical structure is not always the origin of chronic low back pain, but having a greater psychological association instead.

Fear-Avoidance Model[edit | edit source]

Fear is the emotional reach to a specific, identifiable and immediate threat, such as a dangerous injury (Rachman, 1998) and may protect the individual from impeding danger as it instigates defensive behaviour that is associated with the fight or flight response (Cannon, 1929).

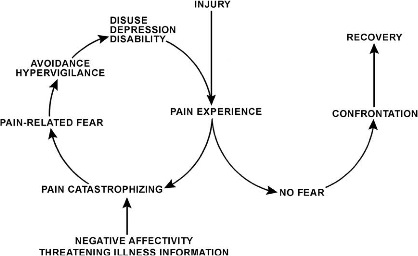

It is a model that was designed to identify and explain why chronic low back pain problems and associated disability develop in members of the population suffering from an onset of low back pain (Leeuw et al., 2007). This model indicates that a person suffering from pain will undergo one of two different pathways (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Fear Avoidance Model (REF)

This shows that when pain/injury occurs, people will take the path of continuing their independence without negative thoughts of the pain they are suffering from, therefore leading them to accept that they have this pain that ultimately accumulates to a faster recovery. In contrast to this, a cycle can be initiated if the pain is misinterpreted in a catastrophising manner. It has been recognised that these thoughts can lead on to pain-related fear and associated safety seeking behaviours such as avoidance. However this could cause the pain to become worse and enter a chronic phase due to the disuse and disability, which in turn can lower the threshold at which the person will experience pain.

Yellow Flags[edit | edit source]

Flags in Physiotherapy are a marker of risk factors regarding musculoskeletal diseases and disorders. Yellow Flags are an indication of Psychosocial factors (Depression, Anxiety etc..) and the patient’s beliefs about their condition (CSP, 2007).

While performing a Yellow Flag assessment, the following should be acknowledged:

Attitudes/Beliefs – What does the patient think to be the problem and do they have a positive or negative attitude to the pain and potential treatment.

Behaviour – Has the patient changed their behaviour to the pain? Have they reduced activity or compensating for certain movements. Early signs of catastrophising and fear-avoidance?

Compensation – Are they awaiting a claim due to a potential accident? Is this placing unnecessary stress on their life? (Sheffield Back Pain, 2014)

Diagnosis/Treatment – Has the language that has been used had an effect on patient thoughts? Have they had previous treatment for the pain before, and was there a conflicting diagnosis? This could cause the patient to over-think the issue, leading to catastrophising and fear-avoidance.

Emotions – Does the patient have any underlying emotional issues that could lead to an increased potential for chronic pain? Collect a thorough background on their psychological history.

Family – How are the patient’s family reacting to their injury? Are they being under-supportive or over-supportive, both of which can effect the patient’s concept of their pain

Work – Are they currently off work? Financial issues could potentially arise? What are the patient’s thoughts about their working environment?

Background [edit | edit source]

CBT is a method that can help manage problems by changing the way patients would think and behave. It is not designed to remove any problems but help manage them in a positive manner (Beck, 1995; NHS Choices, 2012).

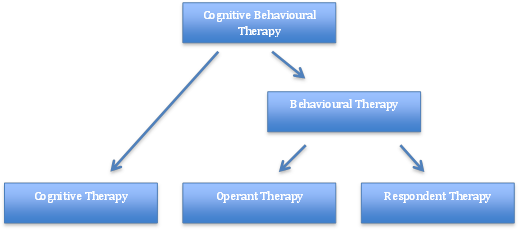

Behaviour therapy (BT) was developed in the 1950’s independently in three countries: South Africa, USA and England (Öst, 2008). It was further developed to Cognitive Therapy (CT) in the 1970’s by Aaron Beck with its main application on people with depression, anxiety and eating disorders (Beck, 1995; Hayes, 2004). However the main evidence today is focusses on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), after the merging of BT and CT in the late 80’s (Roth and Fonagy, 2005).

Fig.2 - Breakdown of CBT theory

Model of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

Bio-PsychoSocial Model[edit | edit source]

Principles of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

There are 3 basic principles of CBT (Butler, 2010):

• How people think about their situations influences how they feel and what they do.

• Problems like depression, anxiety and self-defeating behaviour can be broken down by problematic thought patterns.

• People can learn to identify distorted thinking, change their outlook, take constructive action, and feel better.

Advantages and Disadvantages [edit | edit source]

| Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| The highly structured nature of CBT means it can be provided in different formats, including in groups, self-help books and computer programs. |

Does not use a holistic approach to patient’s situation. |

| Skills learnt through CBT are useful, practical and helpful strategies that can be incorporated into daily lifestyle and benefit the management with future stresses and difficulties. |

Due to the structured nature of CBT, it may not be suitable for people with more complex mental health needs or learning difficulties. |

| Commitment is required from the patient. A therapist can help and advise them, but may be unsuccessful without co-operation from the patient. |

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Therapy[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Therapy was developed and pioneered by Dr Aaron Beck in the 1960’s. During this time, it was employed as an information-processing model to understand and treat psychopathological conditions.

Cognitive Therapy - The Theory[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Therapy, as mentioned above, is one part of the entire CBT model and an approach to treating chronic pain. This process proposes that distorted or dysfunctional thinking can influence a patient’s mood and psychological beliefs, which has been found to coincide with chronic pain (Beck, 1995; Dersh et al., 2002; McWilliams et al., 2003).

Cognitive Therapy involves the identification and replacement of misrepresented thoughts and beliefs that a patient could be feeling. Cognitive Therapy is a problem-solving treatment that is based on the principle that the way we perceive situations and how that influences how we feel about them (Anon., 2014).

The effectiveness of CT has shown positive outcomes regarding depression and anxiety disorders. Alongside these psychological benefits, it has provided positive concerning certain medical issues including chronic fatigue syndrome and other chronic pain disorders (Beck Institute, 2004).

Fig.2 Concept of Cogntive Therapy (REF)

Principles of Cognitive Therapy[edit | edit source]

There are 5 principles of Cognitive Therapy that patients learn throughout each individual session:

• Distinguishing between thoughts and feelings

• Becoming aware of the ways that thoughts can influence feelings in ways that can be detrimental and harmful.

• Learning about thoughts that seem to occur automatically, without even realising how they may affect emotions.

• Critical evaluation of whether these automatic assumptions are accurate.

• Developing skills to notice, interrupt and correct these thoughts independently (ABCT, 2014).

Cognitive Therapy on Chronic Low Back Pain- The Evidence

[edit | edit source]

Limited evidence of Cognitive Therapy on the effect of Chronic Low Back Pain is available (Turner and Jenson, 1993). The randomised controlled trial investigated the efficacy of Cognitive Therapy for CLBP. The effects of group Cognitive Therapy, Relaxation Training and Cognitive Therapy in combination with Relaxation Training were on CLBP and associated physical and psychological disability, were compared. All 3 interventions were reviewed at a 6 and 12 month follow up from baseline. Results concluded that all 3 interventions had a significant improvement on pain intensity, depressive symptoms and disability at both stages of follow up. However no significant difference was found between all 3 of these interventions.

Behavioural Therapy [edit | edit source]

NEED SMALL AMOUNT OF INFO RE: BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY (SEE COGNITIVE THERAPY)

Operant Therapy[edit | edit source]

Operant therapy is based on the Operant Conditioning principles first proposed by Skinner in 1953 in his book Science and Human Behaviour. The Operant behavioural model was first applied to CLBP by Fordyce W E in 1976 in his book Behavioural Methods for Chronic pain and Illness (Henschke et al., 2010).

Operant Therapy - The Theory[edit | edit source]

Operant Behavioural Therapy or Operant Conditioning proposes that pain behaviours learnt by an individual can be reinforced by external factors (Henschke et al., 2010) (Shinohara et al., 2013). The external factors are damaging positive reinforcements of the pain behaviours used by the patient that can be detrimental to the long term health of the patient. These factors often include detrimental attention from family, medical personnel, dependency on pain medication and excessive rest. Therefore operant behavioural therapy looks at removing these damaging positive reinforcements and replacing them with more healthy behaviour. Operant behavioural techniques often involve the use of increased exercise levels and work to meet targets set by the patient and clinician. This method can also be helped by incorporating the family and friends of the patient to maintain and monitor the change back to more healthy behaviours. With each goal that is achieved the patient is positively reinforced by all staff and personnel, involved (Henschke et al., 2010).

VIDEO OF SHELDON HAHAHA

Uses in Clinical Practice[edit | edit source]

Operant Therapy is used in a variety of clinical settings (Shinohara et al., 2013). Operant therapy is primarily used to treat psychological issues such as depression and anxiety. Operant therapy has also been used as part of a Multi-disciplinary approach to treating long term conditions such as CLBP and Fibromyalgia (Thieme et al., 2007; Henschke et al., 2010). Thieme et al. (2007) looked at the effects of Operant Behaviour therapy on 125 Fibromyalgia patients after a 12 month Follow up which showed that 53.5% of patients in the operant therapy group had meaningful improvements in pain intensity.

Respondant Therapy - The Theory[edit | edit source]

Respondent therapy is an approach to behavioural therapy with aims to modify the body’s physiological response to pain, by reducing muscular tension (Henschke et al., 2010). The respondent model as described by Gentry and Bernal (1977) theorises that physical damage can lead to a pain-tension cycle.

Pain tension cycle [edit | edit source]

This cycle is viewed as a cause and a result of muscular tension (Turk 1984). It states that whilst avoidance of movement may be used to reduce pain, the resulting decreased mobility may increase the tension and thus pain furthermore. Respondent therapy aims to disrupt this cycle using methods such as relaxation, progressive relaxation, applied relaxation and Electromyographic (EMG) feedback. These methods are used to reduce the muscular tension, relieving anxiety and thus the subsequent pain (Turk 1984; Vlaeyen 1995).

Techniques for Respondent Therapy[edit | edit source]

Progressive relaxation is a technique for learning to monitor and control the state of muscular tension (Jacobsen, 1929). It was developed by American physician Edmund Jacobson in the early 1920s. The technique involves learning to monitor tension in each specific muscle group in the body by deliberately inducing tension in each group. Upon releasing this tension, attention is paid to the contrast between tension and relaxation. It is to be noted that these are not considered to be exercises or hypnotism.

The “Applied Relaxation” protocol developed in Sweden by the psychologist Lars-Goran Öst developed from Jacobson’s progressive relaxation technique. It expands on progressive relaxation but involves attempting to relax more quickly and in various scenarios (Öst, 1987).

EMG feedback, in respondent therapy, is used as a point of reference for a patient, to objectify their muscle relaxation techniques (Nouwen, 1983). It uses several surface electrodes to detect the action potentials of muscles giving appropriate feedback as to the state of muscle contraction.

Evidence for Respondent Therapy[edit | edit source]

Several studies have compared respondent therapy using progressive relaxation to a placebo (Stuckey et al., 1986; Turner 1982; Turner et al., 1993). Results showed favourable effects of the treatment but not significantly as the waiting list control also showed improvements.

Four studies have identified respondent therapy with EMG feedback against a placebo (Bush et al., 1985; Newton-John et al., 1995; Nouwen, 1983; Stuckey et al., 1986). These studies showed slightly favourable results but producing no significant results.

Evidence of effectiveness against other forms of therapy[edit | edit source]

One study compared respondent therapy against self-hypnosis (McCauley et al., 1983), concluding that neither intervention were superior to the other, given its non-significant results as compared to a placebo.

Evidence of effectiveness of respondent therapy in addition to other treatments[edit | edit source]

One study compared a combination of respondent therapy with EMG feedback and physiotherapy with physiotherapy alone (Magnusson et al., 2008). Significant differences noted in favour of the combination for pain post-treatment, after 6 weeks and 6 months.

Principles of Behavioural Therapy[edit | edit source]

Evidence of Behavioural Therapy on CLBP[edit | edit source]

Cognitive vs Behavioural Therapy on CLBP - The Evidence[edit | edit source]

A study (Nicholas et Al., 1991) compared cognitive and operant therapy. Both groups also received physiotherapy is the form of an exercise programme and education for the management of back pain. The operant therapy group reported a significantly improvement in general function status, but did not find the same results for pain intensity. The quality of this study is in question however; as a systematic review by Middelkoop et al. (2011) reported that the study has a high risk of bias.

Two studies (Turner 1982; Turner, Jenson 1993) compared cognitive therapy to respondent therapy in the form of progressive relaxation training. Only one of these studies (Turner, Jenson 1993) reported on long-term pain and disability, and these outcomes were not statistically significantly different between the groups. The review by Middelkoop et al. (2011) also found these studies to have a high risk of bias.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy on Chronic Low Back Pain - The Evidence[edit | edit source]

Previous research has shown CBT to be an effective form of therapy on Chronic Low Back Pain (CLBP) (Turner, 1982; Reid et al., 2003; Schweikert et al., 2006). Reid et al. (2003) researched the feasibility and potential efficacy of CBT in the elderly population. At 2 weeks post-treatment, positive short term effects were found with a significant reduction in ‘levels of pain intensity’ and ‘pain-related disability’ compared to pre-treatment scores. However, treatment effects waned by the 24 week and although it did not return to pre-treatment scores, participants’ physical and social activity levels did not change. The small sample study was uncontrolled and contained a gender bias of females (86 %) and therefore may not be a true representation of the population. In contrast, Turner (1982) and Schweikert et al. (2006) found positive long term effects. When comparing CBT to progressive-relaxation therapy, a significant continuous improvement was demonstrated in CBT group from 1 month post-treatment to up to 2 years post-treatment when using several measures of pain, depression, and disability. Both treatment groups found a reduction in health-care time and CBT group significantly found more participants spent their time working.

A prospective randomised controlled trial investigated return to work and cost-effectiveness of the addition of CBT to standard therapy compared to standard 3-week inpatient rehabilitation for patients with chronic low back pain (Schweikert et al., 2006). Findings indicated there were no significant differences between the 2 groups in quality-adjusted life-years gained or in direct medical or nonmedical costs. Although the study was not in pounds sterling, the CBT group produced lower indirect costs as subjects were absent from work 5.4 days less than the usual care group 6 months post-rehabilitation.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.