Congenital torticollis

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Congenital torticollis is a postural, musculoskeletal deformity evident at, or shortly after, birth. It results from unilateral shortening and increased tone of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle and presents as lateral flexion of the head to the ipsilateral side with rotation to the contralateral side.

- It is the third most common congenital musculoskeletal condition in newborns with an incidence ranging from 0.3 to 16%.

- Has been associated with dysfunction in the upper cervical spine and is sometimes referred to as kinetic imbalance due to subocciptal strain.

Treatment approaches for CMT include manual therapy (including practitioner-led stretching exercises), repositioning therapy (including tummy time) and, in severe non-resolving cases, botulinum and surgery. CMT can lead to secondary changes such as cranial asymmetry (plagiocephaly), and also to functional problems, including breastfeeding problem[1]

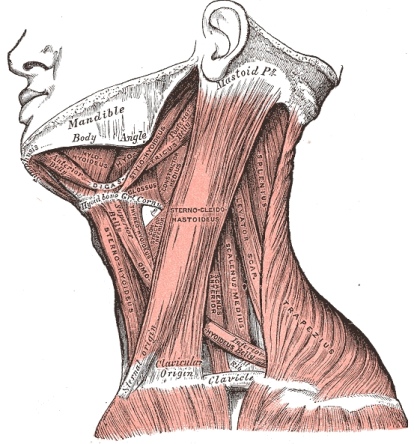

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The sternocleidomastoid muscle has a sternal and clavicular head. The sternal head is directed from the manubrium sterni superiorly, laterally and posteriorly and the clavicular from the medial third of the clavicle vertically upward. It runs to the mastoid process. It enables an ipsilateral lateral flexion and a contralateral rotation. The muscle extends the upper part of the cervical spine and flexes the lower part[2].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The etiology of congenital torticollis remains unknown, although there are several theories. However, there is no proof for any of them. The most cited are ischemia, trauma during childbirth, and intrauterine malposition (pelvic position).

The muscles of the neck form a complex system. Schematically, two levels are distinguished: superficial (long neck muscles) and deep (paravertebral muscle). The sternocleidomastoid is the most targeted muscle; it is in the anterior region of the neck, where it forms a visible and palpable mass. Its action: performs contralateral rotation, ipsilateral inclination, and flexion of the head. This motor activity results in the tilting of the head and neck toward the side of the affected muscle and rotation to the opposite side. The condition typically gets diagnosed during the neonatal period or infancy[3]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The worldwide incidence rate of congenital torticollis varies between 0.3% and 1.9 %; other studies indicate a ratio of 1 in 250 newborns being the third congenital orthopedic anomaly[3]. There is a preponderance to male sex and first pregnancy.

A 2% incidence of congenital torticollis in traumatic deliveries and 0.3% in non-traumatic deliveries.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

In congenital muscular torticollis, the palpable mass in the sternocleidomastoid muscle is mostly made up of fibrous tissue. This mass usually disappears during infancy and is replaced by a fibrous band. The muscle biopsies and MRI studies of the mass revealed that there could be a component of muscle injury, possibly due to compression and stretching of the muscle.

The venous neck compression during childbirth may also have contributed to the decreased blood supply and subsequent compartmental syndrome. Histological studies of material collected at delivery showed edema, muscle fiber degeneration, and fibrosis. These results corroborate the presence of compartment syndrome[3]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

CMT is characterized by a unilateral contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle that forces the infant to hold the head tilted toward the affected side with slight rotation of the chin to the contralateral side[4][5][6].The affected side seems to be excessively stronger than the contralateral side. This causes an imbalance in the neck muscles[7]. In some cases the shoulder is elevated on the affected side[6]. It can be accompanied by plagiocephaly, or develop as a result of plagiocephaly [8].

When CMT is left untreated, it can cause fibrosis of the cervical musculature with progressive limitation of head movement, craniofacial asymmetry, and compensatory scoliosis that worsens with age[6].

Congenital muscular torticollis categorizes into three types:

- Postural (20%) – Infant has a postural preference but no muscle tightness or restriction to passive range of motion

- Muscular (30%) – Tightness of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and limitation of passive range of motion

- Sternocleidomastoid mass (50%) – Thickening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and restricted passive range of motion[3]

Generally Postural CMT is the mildest form, with shorter treatment times compared with Sternocleidomastoid mass CMT which may require longer treatment times and more invasive management [8].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acquired torticollis[4]

- Occipitoatlantal Fusion: characterized by partial or total fusion of the atlas to the occipital bone. The altered mechanics of the cervical spine predisposes the atlantoaxial joint to degeneration and potential instability, resulting in a dull, aching pain in the posterior neck with intermittent stiffness and torticollis. MRI and CT with 3D reconstruction are necessary for diagnosing[4].

- Klippel-Feil syndrome[4]

- Sternomastoid tumor: there is a palpable mass on the sternocleidomastoid muscle, this must be conformed with ultrasonography[9]

- Scoliosis[6]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Observation, palpation and movement testing[edit | edit source]

Infants presenting with observable neck/ head/ facial asymmetry should be screened for CMT. In cases of CMT, the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be shortened on the involved side, leading to an ipsilateral tilt of the head and a contralateral rotation of the face and chin[4][7][9][6]. Reduced neck ROM, a palpable sternocleidomastoid mass, a head position preference and/or plagiocephaly may be present [8].

Ultrasound[edit | edit source]

Ultrasonography can clearly distinguish postural torticollis from sternomastoid tumor patients. Normally the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) can be seen as an hypoechoic structure with short echogenic lines that represent normal perimysium. In sternomastoid tumor patients there is an enlargement of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, asymmetry of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, a heterogeneous internal pattern of echogenicity and overall echogenicity with surrounding tissue. In congenital muscular torticollis patients there is a visible alteration in the size and echogenicity of the SCM.

MRI is recommended when either the clinical symptoms do not resolve within 12 months or when there are atypical features of CMT at US. MRI can demonstrate changes in muscle shape and signal intensity.[4][9]

Torticollis is a sign of an underlying disease process. It does not imply a specific diagnosis.[4]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Cervical range of movement testing

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Thorough history taking including birth history, developmental and medical history, family history.

- Observation of any asymmetries including facial, cranial, neck and positional preference and presence of plagiocephaly.

- Observation of skin creases.

- Observation of infant in developmentally appropriate positions to detect asymmetry and screen developmental milestones.

- Cervical active and passive range of movement testing.

- Upper and lower limb ROM screen, checking for hip dysplasia, which can be associated with CMT, and spine asymmetry.

- Pain at rest and during movements.

- Palpation of sternocleidomastoid for size and elasticity and presence of mass.

- Screen of visual tracking.

- Screen muscle tone.

- Identification of Red flags and appropriate onward referral:

- poor tracking

- abnormal muscle tone

- other features inconsistent with CMT

- poor progress with treatment[8].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Manual stretching is the most common form of treatment for congenital muscular torticollis. A good stabilization and correct hand positions are necessary for the success of the stretch. However, every child/parent pair will have other preferences of stretching methods or positions.[9]

An example of a stretching technique: Following stretch requires two persons. Person one stabilizes the shoulders. The other person does the stretching. For a torticollis on the right side, the left side of the face is cupped. The skull is supported with the right hand under the occipital. The left hand is placed on the chin. This hand placement is both for right rotation and left lateral flexion. Slight traction is given and then a right rotation is performed over the available ROM. The stretch is held for 10 seconds. The lateral flexion stretch is also initiated with a slight traction, followed by slight forward flexion and 10° of right rotation. Then the head is moved laterally, so that the left ear approached the left shoulder.[7]

Another stretching technique can be really effective, this technique is using the gravity to assist in the passive stretch for the affected muscle. start the technique by carrying the baby where he/she is facing away from you. (For example if the child has left torticollis) carry the child with his/her head placed on your left shoulder and then place your right arm between his/her legs and reach his/her left shoulder, then gently depress their left shoulder (push it downward), and with your left hand gently lift his/her head up till the right ear is contacted with the right shoulder (or as higher as the baby can tolerate) then hold from 20 seconds up to one minute (the time could be increased according to the cooperation level of the baby). Advice the parents to play with their baby and distracting him/her from the pain.

Conservative management also includes educating the parents/caregivers about positioning and handling skills that promote active neck rotation toward the affected side and discouraging children from tilting their head toward the affected side.[7][9]

Kinesio Taping is a possible addition to the physical therapy management. Powell (2010) concluded from three case studies that kinesio taping might decrease treatment duration due to longer lasting efficacy with Kinesio application.[2] Öhman (2012) concluded kinesio-taping had an immediate effect on muscular imbalance in children with congenital torticollis.[10]

Kinesio Taping of Sternocleidomastoid muscle: on the affected side from insertion to origin with 5-10% tension, on the unaffected side from origin to insertion with 10-15% tension.[2]

Mean treatment duration and predictive factors were studied by C. Emery (1994). The mean treatment of children with congenital muscular torticollis was 4.7 months. Children with palpable masses in the sternocleidomastoid muscle are generally younger and have more severe restrictions in ROM. They were treated longer (6.9 months) than children with no palpable mass (3.9 months).

Children received a tubular orthosis for torticollis (TOT) when at the 4.5 months of age or older there was a head tilt of more than 6°. The TOT was essentially a collar made of soft tubing, which the child wore while awake as an active correcting device. Their treatment time was longer (7.2 months) than the time needed in children who didn’t need the orthosis (3.6 months).

The severity of restriction of neck rotation was seen as a significant predictor in children with no palpable intramuscular fibrotic sternocleidomastoid muscle mass.

Age at initial assessment, side of involvement and gender were no significant predictors of treatment duration.[7]

Most of the children under one year of age can be treated conservatively.[9]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

If conservative treatment is not successful botox[8] or surgical options may be considered. These include subcutaneous tenotomy, open tenotomy, bipolar tenotomy, and radical resection of a sternomastoid tumour or the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Traditionally, the operative treatment of congenital muscular torticollis has been largely determined by the age of the patient. Although some authors[11] have suggested that operations should be performed within a few weeks of birth, later reports[12] have shown spontaneous resolution of symptoms within a year of birth, or there were satisfactory results with conservative treatment, such as bracing, exercise and massage.

An operation performed too early, particularly before one year of age creates problems in post-operative wound management owing to easier formation of haematomas and increased prevalence of infection. Therefore, some authors have reported that the optimal time for operation is between one and four years of age. Coventry and Harris[4] reported that operation up to 12 years of age produced good results.

Latest studies[13] suggest that age is not the most important factor when determining the optimal time for operation, and that compliance with a post-operative rehabilitation program is the most important consideration. They suggest that operative treatment of congenital muscular torticollis should be delayed until such compliance is possible.

Resources[edit | edit source]

For a comprehensive look at CMT and evidence-based physiotherapy management:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ellwood J, Draper-Rodi J, Carnes D. The effectiveness and safety of conservative interventions for positional plagiocephaly and congenital muscular torticollis: a synthesis of systematic reviews and guidance. Chiropractic & manual therapies. 2020 Dec;28(1):1-1.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7288527/ (accessed 10.8.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Middleditch A, Oliver J.Functional anatomy of the spine: second edition. Edinburgh; New York: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. (Level of Evidence 5)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Gundrathi J, Cunha B, Mendez MD. Congenital Torticollis.2021 Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549778/ (accessed 8.10.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Haque S, Shafi BB, Kaleem M. Imaging of Torticollis in Children. RadioGraphics. 2012;32(2): 558-571 https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.322105143 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ Petronic I, Brdar R, Cirovic D, Nikolic D, Lukac M, Janic D, et al. Congenital muscular torticollis in children: distribution, treatment duration and outcome. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2010; 45(2): 153-158 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Ta JH, Krishnan M. Management of congenital muscular torticollis in a child: A case report and review. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2012;78(11): 1543–1546. (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Öhman A, Mårdbrink EL, Stensby J, Beckung E. Evaluation of treatment strategies for muscle function in infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2011; 27(7): 463-470 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Kaplan S, Coulter C, Fetters L. Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis: An Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Ped Phys There 2013;25(4):348-394. https://journals.lww.com/pedpt/Fulltext/2013/250 (accessed 21 June 2018)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Tatli B, Aydinli N, Caliskan M, Ozmen M, Bilir F, Acar G. Congenital muscular torticollis: evaluation and classification. Pediatric Neurology. 2006;34(1): 41-44 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ Öhman AM. The immediate effect of kinesiology taping on muscular imbalance for infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Phys Med and Rehabilitation Journal. 2012;4(7):504-8 (Level of Evidence 3)

- ↑ Ling CM. The influence of age on the results of open sternomastoid tenotomy in muscular torticollis. Clin Orthop. 1976;116:142-8. (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ Cheng JC, Tang SP. Outcome of surgical treatment of congenital muscular torticollis. Clin Orthop 1999;362:190-200. (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ Lee Y, Yoon K, Kim YB, Chung PW, Hwang JH, Park YS, et al. Clinical features and outcome of physiotherapy in early presenting congenital muscular torticollis with severe fibrosis on ultrasonography: a prospective study. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2011; 46(8): 1526-1531 (Level of Evidence 2)