Congenital torticollis

Introduction/ Description[edit | edit source]

Congenital torticollis (CMT) is a postural, musculoskeletal deformity evident at, or shortly after, birth. It results from unilateral shortening and increased tone of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle and presents as lateral flexion of the head to the ipsilateral side with rotation to the contralateral side. It can be called as twisted neck or wry neck in simple terms.

The term torticollis is derived from the Latin word tortus, meaning ''twisted'' and collum meaning ''neck.''

Treatment approaches for CMT include manual therapy (including practitioner-led stretching exercises), repositioning therapy (including tummy time) and, in severe non-resolving cases, botulinum toxin (botox) and surgery. CMT can lead to secondary changes such as cranial asymmetry (plagiocephaly), and also to functional problems, including breastfeeding problems.[1]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- It is the third most common congenital musculoskeletal condition in newborns with an incidence ranging from 0.3% to 19.7%.[2]

- It has been associated with dysfunction in the upper cervical spine and is sometimes referred to as kinetic imbalance due to suboccipital strain.

- Torticollis in infants is most commonly caused by congenital muscular torticollis.[3]

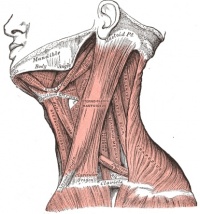

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The sternocleidomastoid muscle has a sternal and clavicular head. The sternal head is directed from the manubrium sterni[4] superiorly, laterally and posteriorly and the clavicular from the medial third of the clavicle vertically upward. It runs to the mastoid process. It enables an ipsilateral lateral flexion and a contralateral rotation. The muscle extends the upper part of the cervical spine and flexes the lower part.[5]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

The aetiology of congenital torticollis is still being explored. The common causes can be ischaemia, trauma during childbirth, with intrauterine pelvic malposition being the most common cause. It can be attributed to altered pelvic spaces often seen during first pregnancies, with decreased amniotic fluid volume, or due to uterine compression syndrome.

Congenital Muscular Torticollis is the most common form observed in infants. It is caused by an imbalance in the sternocleidomastoid muscle which is a part of the complex neck muscles. The increased motor activity of unilateral SCM results in the tilting of the head and neck towards the affected side with contralateral rotation. The condition typically gets diagnosed during the neonatal period or infancy.[6]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

In congenital muscular torticollis, a fibrous band forms in the SCM muscle mainly due to repeated injury as a result of prolonged compression and stretching of the muscle. Histological studies collected at delivery also show edema, muscle fiber degeneration, and fibrosis.[6]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

CMT is characterized by:

- A unilateral contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle causing a head tilt toward the affected side with slight rotation of the chin to the contralateral side[7][8][9].

- The affected side seems to be excessively stronger than the contralateral side. This causes an imbalance in the neck muscles The lateral head righting on contralateral side is weak as compared to the affected side[10].

- In some cases the shoulder is elevated on the affected side[9]. It can be accompanied by plagiocephaly, or develop as a result of plagiocephaly [11].

When CMT is left untreated it can cause-

- Fibrosis of the cervical musculature with progressive limitation of head movement

- Craniofacial asymmetry[12]

- Compensatory scoliosis that worsens with age[9].

Congenital muscular torticollis categorizes into three types:

- Postural (20%) – Infant has a postural preference but no muscle tightness or restriction to passive range of motion

- Muscular (30%) – Tightness of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and limitation of passive range of motion

- Sternocleidomastoid mass (50%) – Thickening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and restricted passive range of motion[6]

Generally Postural CMT is the mildest form, with shorter treatment times compared with Sternocleidomastoid mass CMT which may require longer treatment times and more invasive management [11].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acquired torticollis[7]

- Occipitoatlantal Fusion[7].

- Klippel-Feil syndrome[7]

- Sternocleidomastoid tumour: palpable mass on the sternocleidomastoid muscle, this must be confirmed with ultrasonography[13]

- Scoliosis[9]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis is usually made clinically, with few cases diagnosed through the use of complementary diagnostic tests. Diagnosis is generally before two months in 50% of cases; parents identify most cases and may correlate with plagiocephaly.

- The most common imaging modality is ultrasonography, especially in the neonatal period. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be useful to rule out nonmuscular causes of torticollis.

- Ultrasound is advantageous in assessing neck mass / pseudo-tumor, as well as long-term monitoring and post-treatment evaluation[6].

- Reduced neck ROM, a palpable sternocleidomastoid mass, a head position preference and/or plagiocephaly may be present [11].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical examination is the easiest and most effective means of diagnosis. The most representative assessment methods for assessing congenital torticollis include an assessment of the passive cervical range of motion using an arthrodial goniometer (can be done by physical therapists), as well as an active range of motion, and global assessment. Neurological assessment, as well as auditory assessment, are fundamental to exclude other differential diagnoses[6].

Identification of Red flags and appropriate onward referral: poor tracking; abnormal muscle tone; other features inconsistent with CMT; poor progress with treatment[11].

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There are several ways to approach congenital torticollis, and there is no therapeutic standardization. Professionals in various fields, including physiotherapy and osteopathy, recommend techniques for the treatment of infant torticollis.

With proper treatment, 90% to 95% of children improve before the first year of life, and 97% of patients improve if treatment starts before the first six months[6].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Both physical therapy and repositioning as first line treatment are recommended followed by helmet therapy as a second line of treatment for infants with moderate to severe and persisting asymmetry. Physical therapy is better than positioning pillows due to the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome when sleeping on stomach.

There are a large number of protocol studies in the literature demonstrating the effectiveness of physical therapy.

Little data on the frequency and types of exercise exists

- In many studies, the initial frequency was 2 times per week in the 1st month, progressing to once per week

- Some authors refer 3 times a week initially.

The duration of congenital torticollis physiotherapy treatment depends on the date on which rehabilitation began. The sooner it starts, the faster the normal cervical biomechanics become established, as well as achieving better

Education[edit | edit source]

Education, guidance and support is likely to reassure and help parents.

- Educate the parents/caregivers about positioning and handling skills that promote active neck rotation toward the affected side and discouraging children from tilting their head toward the affected side.[10][13]

Manual stretching[edit | edit source]

Initial treatment focus on passive range stretching and close follow up. Parents are advised to perform positioning at schedules such as during feeds; this includes rotation of the chin towards the affected side shoulder. Infants can be placed on their stomach when awake and under supervision to develop motor skills in the prone position. Manual stretches such as flexion, extension, the lateral rotation. Good stabilization and correct hand positions are necessary for the success of the stretch. Every child/parent pair will have other preferences of stretching methods or positions.[13]

Examples of stretching techniques

- Following stretch requires two persons. Person one stabilizes the shoulders. The other person does the stretching.

- For a torticollis on the right side, the left side of the face is cupped. The skull is supported with the right hand under the occipital. The left hand is placed on the chin. This hand placement is both for right rotation and left lateral flexion.

- Slight traction is given and then a right rotation is performed over the available ROM.

- The stretch is held for 10 seconds. The lateral flexion stretch is also initiated with a slight traction, followed by slight forward flexion and 10° of right rotation. Then the head is moved laterally, so that the left ear approached the left shoulder.[10]

Another stretching technique.

- Can be really effective, this technique is using the gravity to assist in the passive stretch for the affected muscle.

- Start the technique by carrying the baby where he/she is facing away from you.

- For example if the child has left torticollis carry the child with his/her head placed on your left shoulder and then place your right arm between his/her legs and reach his/her left shoulder, then gently depress their left shoulder (push it downward), and with your left hand gently lift his/her head up till the right ear is contacted with the right shoulder (or as higher as the baby can tolerate)

- Hold from 20 seconds up to one minute (the time could be increased according to the cooperation level of the baby).

- Advice the parents to play with their baby and distracting him/her from the pain.

This 1.45 minute video shows the above technique.

Kinesio Taping[edit | edit source]

It is a possible addition to the physical therapy management. Powell (2010) concluded from three case studies that kinesio taping might decrease treatment duration due to longer lasting efficacy with Kinesio application.[5] Öhman (2012) concluded kinesio-taping had an immediate effect on muscular imbalance in children with congenital torticollis.[16]

Kinesio Taping of Sternocleidomastoid muscle: on the affected side from insertion to origin with 5-10% tension, on the unaffected side from origin to insertion with 10-15% tension.[5]

Home program[edit | edit source]

There are certain measures that parents can take:

- Place the toys in the direction where the baby must turn their head to see it

- Position the crib or changing table in direction away from the affected side to see you

- Tubular Orthosis for Torticollis (T.O.T) collar[17]

This video shows how to use a T.O.T collar.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

If conservative treatment is not successful botox[11] or surgical options may be considered.

Surgical indications include cases where there is no improvement after six months of manual stretching if there are more than 15-degree defects in passive rotation and lateral bending, the presence of a tight muscular band, or a tumour in sternocleidomastoid. The procedure includes unipolar/ bipolar sternocleidomastoids muscle lengthening, "Z" lengthening, or radical resection of the sternocleidomastoid[6].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Early diagnosis can help in the initiation of prompt non-invasive correction, which will in turn prevent long-term disfiguring skeletal and muscular complications. Open and clear communication between the caregivers, i.e., the parents, therapist and medical personnel will ensure speedy and efficient recovery of the child.[6]

Resources[edit | edit source]

For a comprehensive look at CMT and evidence-based physiotherapy management:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ellwood J, Draper-Rodi J, Carnes D. The effectiveness and safety of conservative interventions for positional plagiocephaly and congenital muscular torticollis: a synthesis of systematic reviews and guidance. Chiropractic & manual therapies. 2020 Dec;28(1):1-1.

- ↑ Kuo AA, Tritasavit S, Graham JM. Congenital muscular torticollis and positional plagiocephaly. Pediatr Rev. 2014;35(2):79-87; quiz 87.

- ↑ Amaral DM, Cadilha RP, Rocha JA, Silva AI, Parada F. Congenital muscular torticollis: where are we today? A retrospective analysis at a tertiary hospital. Porto biomedical journal. 2019 May;4(3).

- ↑ Gray H. Anatomy of the human body. Lea & Febiger; 1878.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Alison Middleditch MC, Jean Oliver MC. Functional anatomy of the spine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005 Sep 30.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Gundrathi J, Cunha B, Mendez MD. Congenital Torticollis. 2023 Jan 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 31747185.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Haque S, Shafi BB, Kaleem M. Imaging of Torticollis in Children. RadioGraphics. Mar 2012; 32(2): 558-571

- ↑ Petronic I, Brdar R, Cirovic D, Nikolic D, Lukac M, Janic D, et al. Congenital muscular torticollis in children: distribution, treatment duration and out come. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2009 Dec 15;46(2):153-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Ta JH, Krishnan M. Management of congenital muscular torticollis in a child: a case report and review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2012 Nov 1;76(11):1543-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Öhman A, Mårdbrink EL, Stensby J, Beckung E. Evaluation of treatment strategies for muscle function in infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2011; 27(7): 463-470 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Kaplan SL, Coulter C, Fetters L. Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis: An Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline FROM THE SECTION ON PEDIATRICS OF THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2013 Dec 1;25(4):348-94.

- ↑ Cheng JC, Tang SP, Chen TM, Wong MW, Wong EM. The clinical presentation and outcome of treatment of congenital muscular torticollis in infants—a study of 1,086 cases. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2000 Jul 1;35(7):1091-6.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Tatli B, Aydinli N, Caliskan M, Ozmen M, Bilir F, Acar G. Congenital muscular torticollis: evaluation and classification. Pediatric Neurology. 2006;34(1): 41-44 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ Öhman AM, Nilsson S, Beckung ER. Validity and reliability of the muscle function scale, aimed to assess the lateral flexors of the neck in infants. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2009 Jan 1;25(2):129-37.

- ↑ Baby Movement Tips. Congenital Torticollis Stretches. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LxGenW5EHxU&t=5s [last accessed 11/28/2021]

- ↑ Öhman AM. The immediate effect of kinesiology taping on muscular imbalance for infants with congenital muscular torticollis. PM&R. 2012 Jul 1;4(7):504-8.

- ↑ Russo KJ, Fragala MA. USE OF THE TOT COLLAR IN CONJUNCTION WITH TRADITIONAL INTERVENTION FOR A CHILD WITH TORTICOLLIS. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2001 Dec 1;13(4):204.

- ↑ My Torticollis Baby. How to Apply TOT Collar (used for Torticollis). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLTv1_j1eMQ&t=1s [last accessed 11/28/2021]