Congenital torticollis

Introduction/ Description[edit | edit source]

Congenital torticollis (CMT) is a condition in infants commonly diagnosed at or soon after birth. The term torticollis is derived from the Latin word tortus, meaning ''twisted'' and collum meaning ''neck.'' This condition is, therefore, also known as twisted neck or wry neck.

CMT occurs when there is reduced length and increased tone of sternocleidomastoid (SCM) on one side. Infants present with lateral flexion on the ipsilateral side (i.e. the side where the SCM is affected) and contralateral rotation.[1]

Treatment approaches for CMT include:[1]

- manual therapy (e.g. therapist-led stretching exercises)

- repositioning therapy (e.g. tummy time)

- botulinum toxin (botox) / surgery may be necessary for more severe cases that do not resolve

Secondary changes associated with CMT can include:[1]

- cranial asymmetry (plagiocephaly)

- functional problems, such as difficulty breastfeeding

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- Torticollis in infants is most commonly caused by CMT[2]

- CMT is the third most common congenital musculoskeletal condition in newborns - its incidence ranges from 0.3% to 19.7%[3]

- It has been associated with upper cervical spine dysfunction and has been called a "kinetic imbalance due to suboccipital strain"[1]

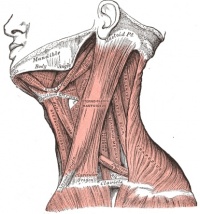

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The sternocleidomastoid muscle has a sternal and clavicular head. The sternal head is originates at the manubrium sterni[4] moving superiorly, laterally and posteriorly. The clavicular originates at the medial third of the clavicle and runs vertically upward. It inserts at the mastoid process and enables ipsilateral lateral flexion and contralateral rotation. SCM also extends the upper part of the cervical spine and flexes the lower part.[5]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

The aetiology of congenital torticollis is still being explored. There are a number of suggested causes, including ischaemia, trauma during childbirth, intrauterine malposition.[6]

CMT caused by intrauterine deformation may be associated with limited space in utero (e.g. in first pregnancies, multiple births), decreased amniotic fluid volume, or uterine compression syndrome.[6]

As mentioned, CMT is caused by an imbalance in the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Increased motor activity of SCM on one side results in ipsilateral side flexion and contralateral rotation.[6]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

A fibrous band forms in the SCM muscle in infants with CMT. This may be due to muscle injury, i.e. prolonged compression and stretching of the muscle. Histological studies also found: oedema, muscle fibre degeneration, and fibrosis in babies with CMT (which suggests the presence of compartment syndrome).[6]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Unilateral contraction of the SCM causing a head tilt toward the affected side with slight rotation of the chin to the contralateral side.[7][8][9]

- Affected side may seem excessively stronger than the contralateral side

- this causes an imbalance in the neck muscles

- the lateral head righting on the contralateral side is weaker than the affected side[10]

- In some cases, the shoulder may be elevated on the affected side[9]

- Can be accompanied by plagiocephaly[11]

When CMT is left untreated, it can cause:

- fibrosis of the cervical musculature - this is associated with progressive limitations in head movements

- asymmetry of craniofacial structures

- compensatory scoliosis - this tends to get worse with age[9]

There are three types of congenital muscular torticollis:[6][11]

- Postural - occurs in 20% of cases - the infant will have a postural preference, but they do not have any muscle restrictions or reductions in passive range of motion

- Muscular - occurs in 30% of cases - the infant will have SCM tightness and a reduction in passive range of motion

- Sternocleidomastoid mass - occurs in 50% of cases - the infant will have thickening of SCM and restricted passive range of motion

Postural CMT is the mildest form of CMT. If identified early, postural CMT is associated with shorter treatment times. Infants with sternocleidomastoid mass and who are identified later (after 3-6 months) tend to require longer interventions and may need more invasive management.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acquired torticollis[7]

- Occipitoatlantal fusion[7]

- Klippel-Feil syndrome[7]

- Sternocleidomastoid tumour: palpable mass on the sternocleidomastoid muscle, this must be confirmed with ultrasonography[12]

- Scoliosis[9]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of CMT can usually be made based on the clinical presentation. The following clinical features may be present:[11]

- reduced neck range of motion

- palpable SCM mass

- head position preference

- plagiocephaly

However, some cases will require complementary diagnostic tests. In 50% of cases, infants are diagnosed before two months of age. Parents are often the ones to identify CMT.[6]

- Ultrasonography (US) is the most frequently used form of imaging, especially for neonates

- it is useful for assessing neck masses, pseudo-tumour

- useful for monitoring/evaluation post-treatment

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to rule out non-muscular causes

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Cervical range of movement testing

- Muscle Function Scale[13]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The assessment for CMT includes:

- passive cervical range of motion with arthrodial goniometer

- active range of motion

- global assessment

- neurological and auditory assessments and visual function to rule out other conditions[6]

Identification of red flags, such as: poor tracking; abnormal muscle tone; other features inconsistent with CMT; poor progress with treatment. If you identify these features, appropriate onward referral is necessary.[11]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There is no standardised treatment for CMT, but with appropriate interventions, it has been found that 90 to 95% of infants will improve before the age of 1 year. If treatment is commenced before 6 months, 97% of infants will improve.[6]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy (stretching, strengthening and developmental facilitation) and aggressive repositioning are first-line treatments, followed by helmet therapy as a second line of treatment for infants with moderate to severe and persisting asymmetry.

There are a large number of protocol studies in the literature demonstrating the effectiveness of physical therapy.

Little data on the frequency and types of exercise exists

- In many studies, the initial frequency was 2 times per week in the 1st month, progressing to once per week

- Some authors refer 3 times a week initially.

The duration of congenital torticollis physiotherapy treatment depends on the date on which rehabilitation began. The sooner it starts, the faster the normal cervical biomechanics become established, as well as achieving better

Education[edit | edit source]

Education, guidance and support is likely to reassure and help parents.

- Educate the parents/caregivers about positioning and handling skills that promote active neck rotation toward the affected side and discouraging children from tilting their head toward the affected side.[10][12]

Manual stretching[edit | edit source]

Initial treatment focus on passive range stretching and close follow up. Parents are advised to perform positioning at schedules such as during feeds; this includes rotation of the chin towards the affected side shoulder. Infants can be placed on their stomach when awake and under supervision to develop motor skills in the prone position. Manual stretches such as flexion, extension, the lateral rotation. Good stabilization and correct hand positions are necessary for the success of the stretch. Every child/parent pair will have other preferences of stretching methods or positions.[12]

Examples of stretching techniques

- Following stretch requires two persons. Person one stabilizes the shoulders. The other person does the stretching.

- For a torticollis on the right side, the left side of the face is cupped. The skull is supported with the right hand under the occipital. The left hand is placed on the chin. This hand placement is both for right rotation and left lateral flexion.

- Slight traction is given and then a right rotation is performed over the available ROM.

- The stretch is held for 10 seconds. The lateral flexion stretch is also initiated with a slight traction, followed by slight forward flexion and 10° of right rotation. Then the head is moved laterally, so that the left ear approached the left shoulder.[10]

Another stretching technique.

- Can be really effective, this technique is using the gravity to assist in the passive stretch for the affected muscle.

- Start the technique by carrying the baby where he/she is facing away from you.

- For example if the child has left torticollis carry the child with his/her head placed on your left shoulder and then place your right arm between his/her legs and reach his/her left shoulder, then gently depress their left shoulder (push it downward), and with your left hand gently lift his/her head up till the right ear is contacted with the right shoulder (or as higher as the baby can tolerate)

- Hold from 20 seconds up to one minute (the time could be increased according to the cooperation level of the baby).

- Advice the parents to play with their baby and distracting him/her from the pain.

This 1.45 minute video shows the above technique.

Kinesio Taping[edit | edit source]

It is a possible addition to the physical therapy management. Powell (2010) concluded from three case studies that kinesio taping might decrease treatment duration due to longer lasting efficacy with Kinesio application.[5] Öhman (2012) concluded kinesio-taping had an immediate effect on muscular imbalance in children with congenital torticollis.[15]

Kinesio Taping of Sternocleidomastoid muscle: on the affected side from insertion to origin with 5-10% tension, on the unaffected side from origin to insertion with 10-15% tension.[5]

Home program[edit | edit source]

There are certain measures that parents can take:

- Place the toys in the direction where the baby must turn their head to see it

- Position the crib or changing table in direction away from the affected side to see you

- Tubular Orthosis for Torticollis (T.O.T) collar[16]

This video shows how to use a T.O.T collar.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

If conservative treatment is not successful botox[11] or surgical options may be considered.

Surgical indications include cases where there is no improvement after six months of manual stretching if there are more than 15-degree defects in passive rotation and lateral bending, the presence of a tight muscular band, or a tumour in sternocleidomastoid. The procedure includes unipolar/ bipolar sternocleidomastoids muscle lengthening, "Z" lengthening, or radical resection of the sternocleidomastoid[6].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Early diagnosis can help in the initiation of prompt non-invasive correction, which will in turn prevent long-term disfiguring skeletal and muscular complications. Open and clear communication between the caregivers, i.e., the parents, therapist and medical personnel will ensure speedy and efficient recovery of the child.[6]

Resources[edit | edit source]

For a comprehensive look at CMT and evidence-based physiotherapy management:

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ellwood J, Draper-Rodi J, Carnes D. The effectiveness and safety of conservative interventions for positional plagiocephaly and congenital muscular torticollis: a synthesis of systematic reviews and guidance. Chiropractic & manual therapies. 2020 Dec;28(1):1-1.

- ↑ Amaral DM, Cadilha RP, Rocha JA, Silva AI, Parada F. Congenital muscular torticollis: where are we today? A retrospective analysis at a tertiary hospital. Porto biomedical journal. 2019 May;4(3).

- ↑ Kuo AA, Tritasavit S, Graham JM. Congenital muscular torticollis and positional plagiocephaly. Pediatr Rev. 2014;35(2):79-87; quiz 87.

- ↑ Gray H. Anatomy of the human body. Lea & Febiger; 1878.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Alison Middleditch MC, Jean Oliver MC. Functional anatomy of the spine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005 Sep 30.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Gundrathi J, Cunha B, Mendez MD. Congenital Torticollis. 2023 Jan 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 31747185.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Haque S, Shafi BB, Kaleem M. Imaging of Torticollis in Children. RadioGraphics. Mar 2012; 32(2): 558-571

- ↑ Petronic I, Brdar R, Cirovic D, Nikolic D, Lukac M, Janic D, et al. Congenital muscular torticollis in children: distribution, treatment duration and out come. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2009 Dec 15;46(2):153-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Ta JH, Krishnan M. Management of congenital muscular torticollis in a child: a case report and review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2012 Nov 1;76(11):1543-6.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Öhman A, Mårdbrink EL, Stensby J, Beckung E. Evaluation of treatment strategies for muscle function in infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2011; 27(7): 463-470 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Kaplan SL, Coulter C, Fetters L. Physical Therapy Management of Congenital Muscular Torticollis: An Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline FROM THE SECTION ON PEDIATRICS OF THE AMERICAN PHYSICAL THERAPY ASSOCIATION. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2013 Dec 1;25(4):348-94.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Tatli B, Aydinli N, Caliskan M, Ozmen M, Bilir F, Acar G. Congenital muscular torticollis: evaluation and classification. Pediatric Neurology. 2006;34(1): 41-44 (Level of Evidence 2)

- ↑ Öhman AM, Nilsson S, Beckung ER. Validity and reliability of the muscle function scale, aimed to assess the lateral flexors of the neck in infants. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2009 Jan 1;25(2):129-37.

- ↑ Baby Movement Tips. Congenital Torticollis Stretches. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LxGenW5EHxU&t=5s [last accessed 11/28/2021]

- ↑ Öhman AM. The immediate effect of kinesiology taping on muscular imbalance for infants with congenital muscular torticollis. PM&R. 2012 Jul 1;4(7):504-8.

- ↑ Russo KJ, Fragala MA. USE OF THE TOT COLLAR IN CONJUNCTION WITH TRADITIONAL INTERVENTION FOR A CHILD WITH TORTICOLLIS. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2001 Dec 1;13(4):204.

- ↑ My Torticollis Baby. How to Apply TOT Collar (used for Torticollis). Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLTv1_j1eMQ&t=1s [last accessed 11/28/2021]