Distal femoral fracture

Top Contributors - Mande Jooste, Angeliki Chorti, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Laura Ritchie, Evan Thomas, Daphne Jackson, Admin, Leen Wyers, Karen Wilson and Claire Knott

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Fracture that occurs at the distal end of the femur bone, that includes the femoral condyles and the metaphysis[1].

Most common types of fractures:

- Transverse fractures

- Comminuted fractures

- Intra-articular fractures

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

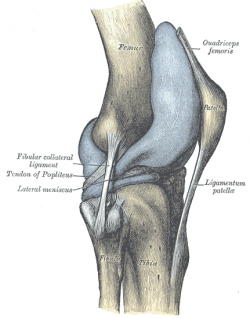

The knee is the largest weight bearing joint of the whole body. The bones of the knee are the distal part of the femur, the upper part of the tibia, and the patella. In the knee joint, there is not only bone, but also a slippery substance which is called the articular cartilage. The function of this cartilage is to protect and to cushion the bones when you move your knee, like when you jump, bend or straighten your knee.

Apart from the bones and the cartilage, there are certain muscles who support the joint and who allow the knee to move. There are two big and strong important muscles. The quadriceps are on the front side and the hamstrings on the back side of the knee. (6 (level of evidence 1B))

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

High energy fractures: usually occurs in young adults (predominantly 30year old males) and results in intra-articular fractures. Mechanism of injury commonly includes motor vehicle accidents, high velocity missile injuries and/ or a direct blow mechanism.

Low energy fractures: mostly occurs in the elderly people, secondary to osteoporosis (predominantly in women over 65years)[2][3][4]. These fractures most commonly occurs with twisting motions or falls.[5]

4-6% of all femur fractures is distal femur fractures, and more than 85%of these occurrences is low energy fractures in the elderly.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Most common symptoms of distal femur fracture include:

- Pain with weight bearing

- Swelling and bruising

- Tenderness to touch

- Deformity.[1] (Shortening of the fracture with varus and extension of the distal articular segment is the typical deformity.3 Shortening is caused by the quadriceps and hamstrings. The varus and extension deformities are due to the unopposed pull of the hip adductors and gastrocnemius muscles respectively.)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Clinical/Physical examination: the typical clinical picture during the inspection of the knee is swelling in the knee region and clear dislocation.

Radiographic examination: AP and lateral views of the Femur.

CT-scans: Highly recommended with high energy trauma and if a intra-articular fracture is suspected. (55% of distal femur fractures are intra-articular.)

[3]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (see Outcome Measures Database)

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Surgical management for distal femur fractures is since the 1970s regarded superior to non-surgical management.[4]

Surgical interventions:

A soft-tissue friendly attitude centered on retrograde intramedullary nailing and plate fixation by minimally invasive percutaneous plate osteosynthesis (MIPPO) and transarticular approach and retrograde plate osteosynthesis (TARPO).

Nonsurgical interventions:

- Skeletal traction 1: 5 (level of evidence 5)

- Skeletal traction 2: 7 (level of evidence 1B)

- Casting and bracing 1: 4 (level of evidence 3A),

- Casting and bracing 2: 5 (level of evidence 5)

Physical Therapy Management

Post operative management[edit | edit source]

- Wound dressings post-op as well as 2days post-op, or as directed by the operating doctor.

- 10-14 days post-op removal of stitches

- Mobilise with two elbow crutches; gait training; Usually PWB (15kg) (WB status is to be confirmed by the operating doctor as it is patient/ case specific)

- Stair climbing after 7-14days

- 6 weeks post-op control X-ray

- Depending on the fracture type and appearance of callus formation, you can increase weight bearing. [6]

Physiotherapy specific aims:

The aim of physiotherapeutic sessions is to gain back the full mobility of the knee and teaching the patient to walk again. At first the whole flexion and extension has to be back before we start walking. We also need to recover the power of the M. quadriceps and the M. hamstrings, this is very important because these are dynamic stabilizers of the knee. After the removal of the plaster we need to start as soon as possible with flexion and extension exercises. There is one condition before we start with the flexion exercises, pressure on the fracture is allowed.

Stepping can be started when there is an acceptable functional range, this means that the knee is stable enough for doing the activities of daily living. The next factors are an obstacle for the functional range. When there is a lack of extension in the knee, exercises of the M. quadriceps are recommended. There can also be a lack of flexion. When there is less than 100° of flexion, the patient has difficulties with steps, deep tread and narrow stairs. The patient needs at least 80-90° of flexion to permit sitting. It’s therefore important that the physiotherapist mobilizes the knee.

In supracondylar fractures the necessary degree of flexion can be obtained using pearson knee flexion peace. Or using a Tomas splint traction at the level of the fracture. Thomas Splint Traction may be used for the first 1 – 2 weeks. Mobilization of the knee should be started as early as possible to avoid tethering adhesions between M. quadriceps and fracture of the knee that cause stiffness in the knee. Unicondylar fractures are for surgical reasons better to rest in a non weight plaster for a period of 6 weeks before starting vigorous mobilization. The importance of performing frequent mobilization should be stressed to the patient. Passive mobilization of the patella in appropriate cases may be helpful. In routine cases of Distal femoral fractures a full range of flexion is achieved in the majority of all cases in the 12 months with the most gain in the first 3 months. (1)

According to current knowledge and evidence based recommendation, ultrasound is used to facilitate bone fracture healing. (3)(4 (level of evidence 3A))(9(level of evidence 1A)).But ultrasound hasn’t long-terms effects.(10(level of evidence 1A))

Complications[edit | edit source]

Malunion

Delayed union

Non-union (or breakage of plate)

Implant failure[3]

Infection (superficial infection or deep infection)

Limited range of motion

Leg length discrepancy[7]

Ligamentous instability[6]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Intra-articular physeal fractures[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Crist B, Della Rocca G, Murtha Y. Treatment of Acute Distal Femur Fractures. ORTHOPEDICS. 2008; 31: doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080701-04

- ↑ Streubel P, Ricci W, Wong A, Gardner M. Mortality After Distal Femur Fractures in Elderly Patients. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research [Internet]. 2011 Apr 1 [cited 2019 Apr 2];469(4):1188–96. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoah&AN=22177572&site=pfi-live

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hoskins W, Bingham R, Griffin XL. Distal femur fractures in adults. Orthopaedics and Trauma [Internet]. 2017 Apr 1 [cited 2019 Apr 2];31(2):93–101. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoah&AN=40511626&site=pfi-live

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ehlinger M, Ducrot G, Adam P, Bonnomet F. Minimally invasive internal fixation of distal femur fractures. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, 2017-02-01, Volume 103, Issue 1, Pages S161-S169.

- ↑ Mashru RP, Perez EA. Fractures of the distal femur current trends in evaluation and management. Current Opinion in Orthopaedics [Internet]. 2007 Feb 1 [cited 2019 Apr 2];18(1):41–8. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoah&AN=48551848&site=pfi-live

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Schandelmaier P, Blauth M, Krettek C. Internal Fixation of Distal Femur Fractures with the Less Invasive Stabilizing System (LISS). Orthopaedics and Traumatology [Internet]. 2001 Sep 1 [cited 2019 Apr 2];9(3):166–84. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoah&AN=2132445&site=pfi-live

- ↑ El-Tantawy A, Atef A. Comminuted distal femur closed fractures: a new application of the Ilizarov concept of compression–distraction. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology [Internet]. 2015 Apr 1 [cited 2019 Apr 2];25(3):555–62. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eoah&AN=34329802&site=pfi-live

- ↑ Pennock, AT., Ellis, HB., Willimon, SC., Wyatt, C., Broida, SE., Dennis, MM., & Bastrom, T. Intra-articular Physeal Fractures of the Distal Femur: A Frequently Missed Diagnosis in Adolescent Athletes. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine, 5(10). 2017. 2325967117731567. doi:10.1177/2325967117731567

This injury article requires improvement to meet Physiopedia's quality standards. The reasons have been specified below this alert box. Please help improve this page if you can. #qualityalert #qualityalert_injury

To edit: referencing format, ?research update

Resources[edit | edit source]

(1) Ronald Mcrae/ Max Esser, Practical fracture treatment, Fourth edition, 2002, p.321-328

(2) Ebenbichler G. – Evidence-based medicine and therapeutic ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system – Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie – September 2009 – p.543-548

(3) Warden SJ et al. - Facilitation of fracture repair using low-intensity pulsed ultrasound – Veterinary and comparative orthopaedics and traumatology – December 2000 – p. 158-164

(4) Healio Orthopaedics - Treatment of Acute Distal Femur Fractures

(http://www.healio.com/orthopedics/journals/ortho/%7Bea445a00-7883-48d2-8e86-7eb7aa140d0c%7D/treatment-of-acute-distal-femur-fractures) (level of evidence 3A)

(5) OrthoInfo - Distal Femur (Thighbone) Fractures of the Knee

(http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00526#top) (level of evidence 5)

(6) Higgins TF - Distal femoral fractures - The Journal of Knee Surgery - 2007, 20(1):56-66

(6) http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17288091) (level of evidence 1B)

(7) E. M. Winant – The use of skeletal traction – New York – 1949 (level of evidence 2A)

(8) Dr. P.R.G. Brink et al. - Letsels van het steun- en bewegingsapparaat, 2000, p.225-231

(9) Markus D. Schofer et al. - Improved healing response in delayed unions of the tibia with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound: results of a randomized sham-controlled trial BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 11:229 – 2010 (level of evidence 1A)

(10) Handolin L. Et al. – No long-term effects of ultrasound therapy on bioabsorbable screw-fixed lateral malleolar fracture - Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 94: 239–242 – 2005 (level of evidence 1A)

References[edit | edit source]

1) Ronald Mcrae/ Max Esser, Practical fracture treatment, Fourth edition, 2002, p.321-328

2) Dr. P.R.G. Brink et al. - Letsels van het steun- en bewegingsapparaat, 2000, p.225-231

3) Ebenbichler G. – Evidence-based medicine and therapeutic ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system – Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie – September 2009 – p.543-548

4) Warden SJ et al. - Facilitation of fracture repair using low-intensity pulsed ultrasound – Veterinary and comparative orthopaedics and traumatology – December 2000 – p. 158-164

5) Healio Orthopaedics - Treatment of Acute Distal Femur Fractures (http://www.healio.com/orthopedics/journals/ortho/%7Bea445a00-7883-48d2-8e86-7eb7aa140d0c%7D/treatment-of-acute-distal-femur-fractures) (level of evidence 3A)

6) OrthoInfo - Distal Femur (Thighbone) Fractures of the Knee

(http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00526#top) (level of evidence 5)

7) Higgins TF - Distal femoral fractures - The Journal of Knee Surgery - 2007, 20(1):56-66 (http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17288091) (level of evidence 1B)

8) E. M. Winant – The use of skeletal traction – New York – 1949 (level of evidence 2A)

9) Markus D. Schofer et al. - Improved healing response in delayed unions of the tibia with low-intensity pulsed ultrasound: results of a randomized sham-controlled trial BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 11:229 – 2010 (level of evidence 1A)

10) Handolin L. Et al. – No long-term effects of ultrasound therapy on bioabsorbable screw-fixed lateral malleolar fracture - Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 94: 239–242 – 2005 ( level of evidence 1A)