Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

* Perceptual-motor therapy | * Perceptual-motor therapy | ||

* Sensory integration training | * Sensory integration training | ||

These | These emerging physiotherapy techniques will all be discussed later! | ||

==== '''''What Can You Do to Help?''''' ==== | ==== '''''What Can You Do to Help?''''' ==== | ||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

# <u>The Earlier the Better</u>: Starting balance practice early in a child’s life will allow for greater amount of learning time and increase muscle strength at a young age. | # <u>The Earlier the Better</u>: Starting balance practice early in a child’s life will allow for greater amount of learning time and increase muscle strength at a young age. | ||

# <u>It’s Never Too Late</u>: Though it is harder to correct learned bad habits, practice at any time is helpful. It is never too late to start. | # <u>It’s Never Too Late</u>: Though it is harder to correct learned bad habits, practice at any time is helpful. It is never too late to start. | ||

FUN FACT: individuals with DS are more commonly visual learners. This means that they learn better by watching others or copying what they can see rather than responding to what is being said. Copy cat is a great game to help teach your child new tasks | FUN FACT: individuals with DS are more commonly visual learners. This means that they learn better by watching others or copying what they can see rather than responding to what is being said. Copy cat is a great game to help teach your child new tasks<ref>Welsh TN, Elliot D. The processing speed of visual and verbal movement information by adults with and without Down syndrome. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 2001;18:156-167.</ref>! | ||

== Common Myths Debunked == | == Common Myths Debunked == | ||

Revision as of 15:16, 16 April 2018

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Welcome to our information page! This resource is intended for families and carers of persons with Down syndrome (DS).

When a person has DS, it is common for family members to seek out information to better understand the unique challenges they may face and to prepare for the future. There is a large amount of information available regarding Down syndrome, which can be overwhelming and intimidating.

The purpose of this educational resource is to consolidate and clarify the information found in current literature and provide families of persons with DS a comprehensive, easily understood learning tool that they can feel confident in consulting. This wiki further intends to educate families about what to expect throughout the lifespan of an individual with DS, ease concerns, and highlight the role of physiotherapy in the care and management of Down syndrome. After reading this page, it is the hope of the authors that readers will feel encouraged and confident, allowing the family to better manage and cope at home. We hope that families will be better able to understand when and how to seek professional guidance, should they require support.

Why is this Wiki Important?[edit | edit source]

DS is the most commonly occurring chromosomal variance noted world-wide[1] , with 1 in 700 births resulting in a child with DS[2]. In the UK alone, there are over 41,000 people living with Down syndrome, and 750 new people born with DS each year [3]. Birth rates are expected to stay the same, but the total population of persons with DS is expected to rise in the coming years. This is mainly due to medical advancements which have increased the life expectancy of people with DS from age 9 in 1929, to 60 years of age today [4]. With this increase in number and age of this population, there will be a larger demand on health services and increased challenges for families to overcome. Furthermore, persons with DS report having problems gaining access to health care[5] with the main barrier being a lack of knowledge about available services[6].

This wiki is therefore a necessary educational tool for families to consult whenever they are looking for answers or reassurance. It will also identify what is to be expected over the lifespan of a person with DS and common misconceptions, as well as how families and individuals can best self-manage at home. Lastly, this resource will highlight potential complications and provide resources for family members should they require assistance.

Learning Journey[edit | edit source]

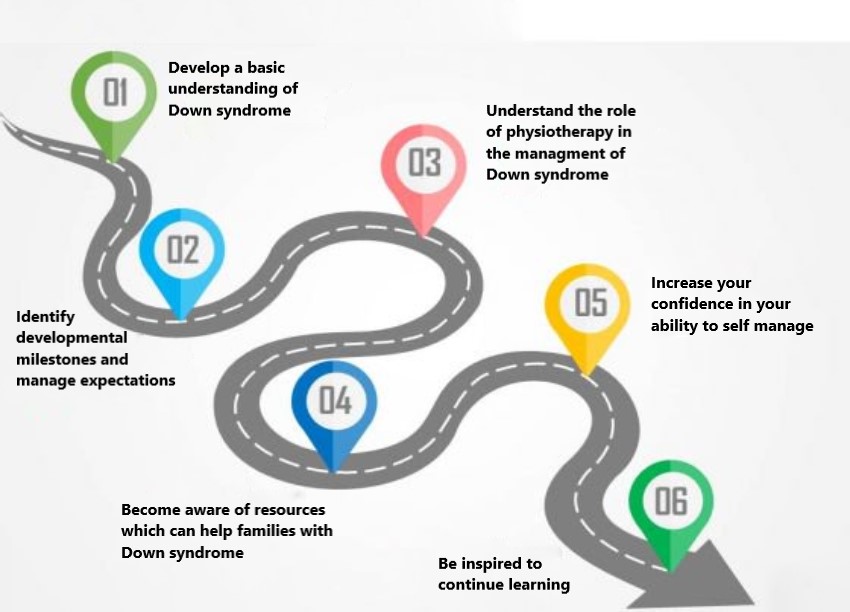

It is the goal of the authors that after reading this page you will:

Introduction to Down syndrome [edit | edit source]

Before we begin, we would like you to watch Ted talk given by Karen Gaffney, a person with Down syndrome. This video will address many contemporary thoughts surrounding DS and ensure you are in the correct mindset about DS while navigating our learning resource. This video provides an inspiring message of positivity that the authors hope to expand upon and pass on to you.

What is Down syndrome?[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, DS is a chromosomal alteration. Chromosomes are structures found in every cell of our body that contain genetic material. Typically, each cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes, with half coming from each parent [7]. Down syndrome however, occurs when chromosome 21 has a full or partial extra copy in some, or all, of that individual’s cells. This triple copy is sometimes called trisomy 21 [8]. The altered number of chromosomes leads to common physical features in the DS population, such as:

DS itself is not a medical condition and is simply a common variation in the human form. However, there are many medical conditions that people with DS frequently experience. These include:

- Learning difficulties

- Poor cardiac health

- Thyroid disfunction

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Digestive problems

- Low bone density

- Hearing and Vision loss

- Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

- Depression

- Leukaemia [10][11][12]

STAY POSITIVE: Keep in mind that every person is unique. These listed conditions are common in DS but are only possibilities, not inevitabilities.

Though there are many similarities across the DS population, there is great variation in the syndrome. There are three types of DS, each with its own set of challenges and individual variation. The three types of DS are Trisomy 21, Translocation and Mosaicism. Further information on the differences between categories can be found here[13].

Whichever the type, persons with DS typically have poorer overall health at a young age and exhibit a greater loss of health, mobility, and increased secondary complications as they age when compared to their non-DS counterparts [14][15]. Physiotherapists are commonly consulted to educate individuals and their families as well as provide input on health promotion and long-term condition management [16]. As treatment often requires ongoing maintenance, physiotherapists have become increasingly reliant on family members to support and implement home treatment plans in an attempt to encourage self-management [17]. Due to the variation in all people and across Down syndrome cases, no one physiotherapy intervention can be prescribed. Interventions are based on the individual’s physical and intellectual needs, as well as his or her personal strengths and limitations [11]. Some of the common issues that physiotherapists will address are:

- Delayed developmental milestones

- Balance issues

- Strength

- Mobility

Physiotherapy Problems[edit | edit source]

Developmental Milestones[edit | edit source]

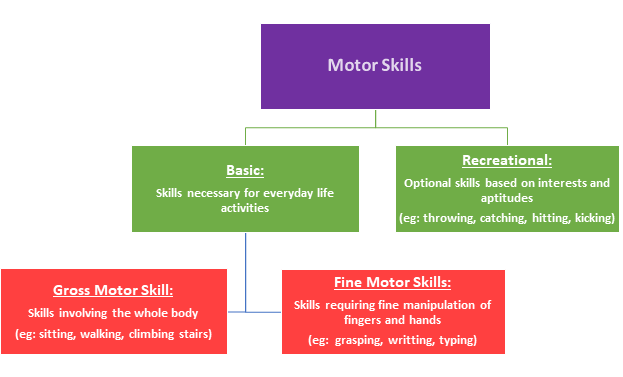

From the time a child is born, they are growing and learning. Each person develops at their own pace. However, some skills are expected to be mastered by a specific age. These are called developmental milestones. Milestones can be physical achievements, language related, or social accomplishments. As physiotherapists, we typically focus on motor skills[12].

The ability to move is essential to human life and development. All children begin developing a wide range of movement skills, or motor skills, starting at birth. These motor skills are wide ranging and often broken down into the sub sections below:

Motor skills are key for physical function, but also impact cognitive development.

- Reaching and grasping allows a child to explore the characteristics of objects in his or her physical world

- Sitting promotes the use of arms and hands for playing

- Walking allows a child to explore the world more effectively than crawling

- Independent movement increases opportunities for social interaction which promotes language learning[1][18]

Persons with DS will generally achieve all the same basic motor skills necessary for everyday living and personal independence, however it may be at a later age and with less refinement compared to those without DS[19]. Children with DS typically earn adequate skills for daily competence! Some adjusted milestones for DS are available below:

For more in depth developmental milestone charts, please see here[21], and if you would like further description of milestones or to track your child’s progress at home, please see checklist provided here[18]. While these milestones are generally agreed upon, studies targeting developmental milestones tend to only examine a small number of people. This makes the information less representative of the entire DS population. Also, researchers commonly compare people with DS to their non-DS counterparts of the same age. This is an invalid comparison, and it would be more correct to compare children with DS to non-DS individuals of the same mental age. Despite these limitations, the above listed milestones are widely used and considered accurate[22].

Physiotherapy for Developmental Milestones[edit | edit source]

Physical characteristics of the child with DS such as low muscle tone, loose joints and decreased strength may limit the speed of mastery or alter the form of the developmental milestone. Persons with DS generally naturally overcome these challenges through perseverance.[1].

The goal of physiotherapy is not to ‘speed up’ the rate of development. It is simply to facilitate the development of optimal movement patterns. Depending upon capabilities and adaptations made, physical compensations such as pain or inefficient walking patterns may occur. Physiotherapists are here to help with that! When considering motor skills in DS, the goal of a physiotherapist is to provide the building blocks to develop a solid physical foundation for movement and exercise in which your family member can build on for the rest of their life.

Physiotherapy sessions focusing on developmental milestones will be specifically tailored to your child’s current level of development. The physiotherapist will observe your child’s abilities and determine what skills should be learned next. As each person is different, skills will be taught in the way your child learns best. It is common for tasks to be broken into smaller parts and practiced using different methods based on individual learning styles and physical make up. A new idea developing in physiotherapy for persons with DS known as ‘tummy time’, discussed below, has also been shown to aid in timely achievement of motor skills Physiotherapists will often get family members involved with treatment. Practice at home is essential for mastery, and your participation is key. The physiotherapist will teach you how to:

- Use your child’s interests to encourage new skill development

- Build on already mastered skills

- Focus on what your child is willing to learn

- Practice often

- Be patient

REMEMBER: When thinking about developmental milestones, the journey to get there may be different, but the destination is the same!

Balance and Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, it is common for children with DS to be delayed in reaching common milestones such as sitting independently, standing and walking. One of the contributing factors to the delay of these specific milestones is poor balance. It is well known that persons with DS are often considered ‘floppy’, ‘clumsy’, uncoordinated and have awkward movement patterns due to balance issues. These balance challenges often follow the child into their teen years and sometimes into adulthood[23]. While impaired balance is difficult on its own, it may also impact development of other motor abilities and cognitive development. Being able to maintain balance allows for exploration, social interaction and overall freedom[24]. This highlights the importance of addressing this issue.

REMINDER: If you notice these qualities, do not worry. This is to be expected and can be improved upon with practice and patience!

What Causes These Balance Challenges?[edit | edit source]

- Loose Ligaments: Persons with DS have elastic/loose joints, allowing for a large range of movement. This may lead to joints being less stable and difficult to control, causing unbalanced behaviours.

- Low Muscle Tone: A symptom of DS is commonly a ‘floppy’ appearance, with little activity in the muscles at rest, impacting stationary balance. Floppiness does improve over time but can influence balance greatly in early years.

- Slow Reaction Times/ Movement Times: Persons with DS often are slower to react and move than their non-DS peers. This means that even if they are aware they are unsteady, they will take a longer time to react to this feeling, and once it is understood, their corrective movement will also be delayed. Both of these aspects add a challenge to balance.

- Differences in Brain Size: Persons with DS typically have smaller cerebellums, which is a part of the brain that contributes to the control of balance. The small size impacts its function, limiting balance reflexes, and causing blurry vision when completing tasks at high speed. Other parts of the brain are also smaller, creating issues with voluntary activities, walking technique and coordination.

- Decreased Postural Control: Typical posture in a person with DS is hunched over, with a rounded neck, which prevents the head and body from sitting over the pelvis. Posture is impacted by inaccurate messages being sent to the brain from the body’s sensory system. This leaves people with DS less capable of adapting or making anticipatory adjustments to changing environments[24][25][26].

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

There are a wide range of physiotherapy interventions that can help your family member improve their balance. Some of them have been used for many years, while others are still developing and being introduced.

Traditional

Some interventions that have been proven to improve balance in persons with DS are: (Gupta et al. 2011)

- Stability Exercise (examples available here[27])

- Corrective positioning (examples here[28])

- Stair climbing

- Yoga

- Hydrotherapy [29][24]

Emerging

- Hippotherapy

- Treadmill training

- Two-wheel bicycle training

- Tummy Time

- Perceptual-motor therapy

- Sensory integration training

These emerging physiotherapy techniques will all be discussed later!

What Can You Do to Help?[edit | edit source]

- Practice Makes Perfect: As with everything in life, practice will improve performance. While it often takes more practice to improve performance of balance in a child with DS, it is possible to increase both speed and accuracy of movement.

- Encourage Independent Movement: When a person actively initiates a movement, the brain learns how to control the area being moved. This improves coordination and task performance.

- Follow Individual Interests: Your child is more likely to eagerly participate if the activity is one that is enjoyed. Try incorporating balance training into sports and games.

- The Earlier the Better: Starting balance practice early in a child’s life will allow for greater amount of learning time and increase muscle strength at a young age.

- It’s Never Too Late: Though it is harder to correct learned bad habits, practice at any time is helpful. It is never too late to start.

FUN FACT: individuals with DS are more commonly visual learners. This means that they learn better by watching others or copying what they can see rather than responding to what is being said. Copy cat is a great game to help teach your child new tasks[30]!

Common Myths Debunked[edit | edit source]

Before we begin, we would like you to watch this short video. This video will address many common misconceptions about DS and ensure you are in the correct mindset about DS while navigating our learning resource.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Continued Learning[edit | edit source]

We realise that this resource was developed with a large emphasis on the role of physiotherapy in the management of Down syndrome. It is likely that you have other questions which have not been answered on this page. Below are links to external websites which we hope will aid in answering any lingering questions.

The Role of Speech and Language Therapists in Down Syndrome

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 National Down Syndrome Society. Down syndrome fact sheet. www.ndss.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NDSS-Fact-Sheet-Language-Guide-2015.pdf (accessed 14 March 2018).

- ↑ Cipriani G, Danti S, Carlesi C, Fiorino M. Aging with down syndrome: the dual diagnosis: alzheimer's disease and down syndrome. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias 2018. www.journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1533317518761093 (accessed 14 March 2018).

- ↑ Carr J, Collins S.. 50 years with down syndrome: a longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29498451 (accessed 14 March 2018).

- ↑ Zhu J, Hasle H, Correa A, Schendel D, Friedmant J, Olsen J, Ramussen S. Survival among people with down syndrome. Genetics in Medicine 2013;15:64-69. https://www.nature.com/articles/gim201293 (accessed 12 March 2018).

- ↑ Allerton L, Emerson E. British adults with chronic health conditions or impairments face significant barriers to accessing health services. Public Health 2012;126:920-927. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22959282 (accessed 13 March 2018).

- ↑ National Health Service. Promoting access to healthcare for people with a learning disability. www.jpaget.nhs.uk/media/186386/promoting_access_to_healtcare_for_people_with_learning_disabilities_a_guide_for_frontline_staff.pdf (accessed 14 March 2018).

- ↑ National Down Syndrome Society. What is down syndrome. London: NDSS. https://www.ndss.org/about-down-syndrome/down-syndrome/ (accessed 19 March 2018).

- ↑ Newton R, Marder L, Puri S. Down syndrome: current perspectives. London: Mac Keith Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qmu/detail.action?docID=3329189 (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Kami T. Signs of Down Syndrome. 2008. [Picture]. www.womens-health-advice.com/photos/down-syndrome.html (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Mazeurek D, Wyka J. Down syndrome: genetic and nutritional aspects of accompanying disorders. Roczniki Panstwowego Zakladu Higieny 2015;66:189-194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26400113 (accessed 17 March 2018).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 National Human Genome Research Institute. Learning about Down syndrome. https://www.genome.gov/19517824/learning-about-down-syndrome/ (accessed 16 March 2018).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Sacks B, Buckley S. What do we know about the movement abilities of children with down syndrome. Down Syndrome News and Updates 2003;2:131-141. https://library.down-syndrome.org/en-gb/news-update/02/4/movement-abilities-down-syndrome/ (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Down Syndrome Limerick. Different types of down syndrome. https://www.downsyndromelimerick.ie/services/new-parents/types-of-down-syndrome (accessed 17 March 2018).

- ↑ British Institute of Learning Disabilities. Supporting older people with learning disabilities. https://www.ndti.org.uk/uploads/files/9354_Supporting_Older_People_ST3.pdf (accessed 18 March 2018).

- ↑ Cruzado D, Vargas, A. Improving adherence physical activity with a smartphone application based on adults with intellectual disabilities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1173. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1173 (accessed 11 March 2018).

- ↑ CSP. Learning disabilities physiotherapy. Associated of Chartered Physiotherapists for People with Learning Disabilities. www.acppld.csp.org.uk/learning-disabilities-physiotherapy (accessed13 March 2018).

- ↑ Middleton J, Kitchen S. Factors affecting the involvement of day centre staff in the delivery of physiotherapy to adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 2008:21:227-235. www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2007.00396.x/epdf (accessed 11 March 2018).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Layton T. Developmental Scale for Children with Down Syndrome. North Carolina: Extraordinary Learning Foundation. www.dsacc.org/downloads/parents/downsyndromedevelopmentalscale.pdf (accessed 20 March 2018).

- ↑ Kim H, Kim S, Kim J, Jeon H, Jung D. Motor and cognitive developmental profiles in children with down syndrome. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine 2017;41:97-103. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5344833/ (accessed 21 March 2018).

- ↑ National Down Syndrome Society. Down Syndrome Developmental Milestones. 2009. [Picture]. https://www.ndss.org/resources/early-intervention/ (accessed 12 March 2018).

- ↑ Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group. PCHR insert for babies born with Down syndrome. Nottingham: Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group. www.healthforallchildren.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/A5-Downs-Instrucs-chartsfull-copy.pdf (accessed 21 March 2018).

- ↑ Frank K, Esbensen A. Fine motor and selfcare milestones for individuals with down syndrome using a retrospective chart review. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology. 2015;89:719-729. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jir.12176 (accessed 20 March 2018).

- ↑ Georgescu M, Cernea M, Balan V. Postural control in down syndrome subjects. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. www.futureacademy.org.uk/files/images/upload/ICPESK%202015%2035_333.pdf (accessed 17 March 2018).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Malak R, Kostiukow A, Wasielewska A, Mojs E, Samborski W. Delays in motor development in children with down syndrome. Medical Science Monitor 2015;21:1904-1910. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4500597/ (accessed18 March 2018).

- ↑ Costa A. An assessment of optokinetic nystagmus in persons with down syndrome. Experimental Brain Research 2011;8:110-121. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/08/110824142850.htm (accessed17 March 2018).

- ↑ Saied B, Hassan D, Reza B. Postural stability in children with down syndrome. Medicina Sportiva 2014;1:2299-2304. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1510494760/fulltextPDF/6606B032D8C04A9EPQ/1?accountid=12269 (accessed19 March 2018).

- ↑ NHS. Balance Exercises. https://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/fitness/Pages/balance-exercises-for-older-people.aspx (accessed 20 March 2018).

- ↑ Down Syndrome Awareness. Our beautiful son with Down syndrome at Physical Therapy [Video]. 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6Mmv0-ShHU(accessed 15 March 2018).

- ↑ Gupta S, Rao B, Kumaran S. Effect of strength and balance training in children with down syndrome: a randomized control trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 2011;25:425-432. www.journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0269215510382929 (accessed 19 March 2018).

- ↑ Welsh TN, Elliot D. The processing speed of visual and verbal movement information by adults with and without Down syndrome. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 2001;18:156-167.

References for Videos[edit | edit source]

BBC Three. Things people with down syndrome are tired of hearing [Video]. 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAPmGW-GDHA (accessed 16 March 2018).

Tedx Talks. I have one more chromosome. So what? [Video]. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwxjoBQdn0s (accessed 12 March 2018).

![[9]](/images/d/de/DS_features.jpg)

![[20]](/images/a/af/Milestones_DS.jpg)