Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

DS itself is not a medical condition and is simply a common variation in the human form. However, there are many medical conditions that people with DS frequently experience. These include: | DS itself is not a medical condition and is simply a common variation in the human form. However, there are many medical conditions that people with DS frequently experience. These include: | ||

[[File:Medical conditions.png|right|frameless|307x307px]] | |||

* Learning difficulties | * Learning difficulties | ||

* Poor cardiac health | * Poor cardiac health | ||

Revision as of 15:48, 22 April 2018

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Welcome to our information page! This resource is intended for families and carers of persons with Down syndrome (DS).

When a person has DS, it is common for family members to seek out information to better understand the unique challenges they may face and to prepare for the future. There is a large amount of information available regarding Down syndrome, which can be overwhelming and intimidating.

The purpose of this educational resource is to consolidate and clarify the information found in current literature and provide families of persons with DS a comprehensive, easily understood learning tool that they can feel confident in consulting. This wiki further intends to educate families about what to expect throughout the lifespan of an individual with DS, ease concerns, and highlight the role of physiotherapy in the care and management of Down syndrome. After reading this page, it is the hope of the authors that readers will feel encouraged and confident, allowing the family to better manage and cope at home. We hope that families will be better able to understand when and how to seek professional guidance, should they require support.

Why is this Wiki Important?[edit | edit source]

DS is the most commonly occurring chromosomal variance noted world-wide [1], with 1 in 700 births resulting in a child with DS [2]. In the UK alone, there are over 41,000 people living with Down syndrome, and 750 new people born with DS each year [3]. Birth rates are expected to stay the same, but the total population of persons with DS is expected to rise in the coming years. This is mainly due to medical advancements which have increased the life expectancy of people with DS from age 9 in 1929, to 60 years of age today [4]. With this increase in number and age of this population, there will be a larger demand on health services, such as physiotherapy, and increased challenges for families to overcome.

Additionally, persons with DS already report having problems gaining access to health care [5] with the main barrier being a lack of knowledge about available services [6]. Furthermore, parents of persons with DS also commonly express stress and uncertainty surrounding care of their child and state that they desire more help from physical activity specialists in realms of both education and intervention[7].

As members of the healthcare team who are commonly consulted regarding the care of persons with DS, physiotherapists will be affected by this population change. Physiotherapy plays a large role in the care of persons with DS and families often spend hours at physiotherapy appointments to help their child. The authors believe that understanding basic physiotherapeutic techniques and exercise principles will help parents feel at ease and provide maximum benefit for their child.

This wiki is therefore a necessary educational tool for families to consult whenever they are looking for answers or reassurance. It will also identify what is to be expected over the lifespan of a person with DS and common misconceptions, as well as how families and individuals can best self-manage at home. Lastly, this resource will highlight potential complications and provide external resources for family members should they require assistance.

Learning Journey[edit | edit source]

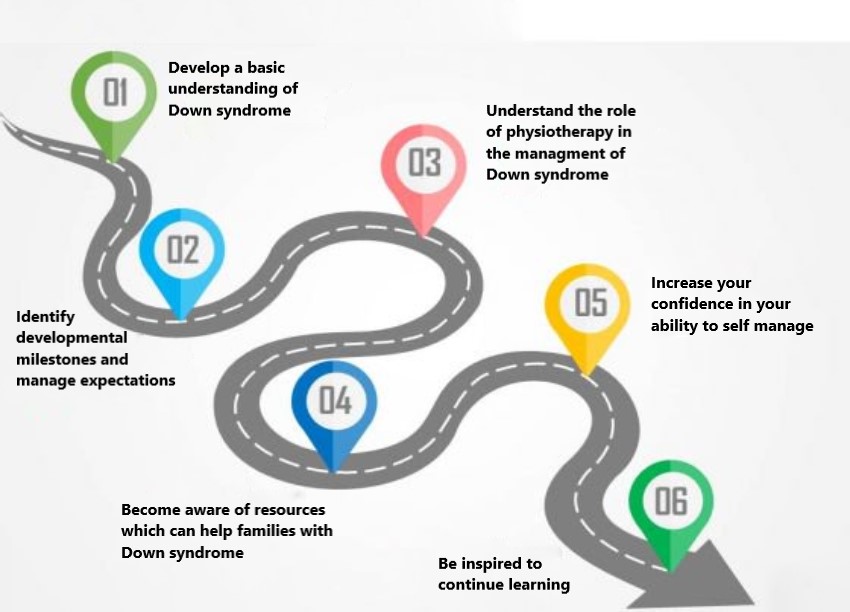

It is the goal of the authors that after reading this page you will:

Before going any further the authors recommend watching this “Ted Talk” given by Karen Gaffney, a person with Down syndrome. This video addresses many contemporary thoughts surrounding DS and will help to ensure you are in the correct mind set while navigating this learning resource. This video provides an inspiring message of positivity that the authors hope to expand upon and pass on to you.

What is Down syndrome?[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, DS is a chromosomal alteration. Chromosomes are structures found in every cell of the body that contain genetic material. Typically, each cell has 23 pairs of chromosomes, with half coming from each parent [8]. Down syndrome however, occurs when chromosome 21 has a full or partial extra copy in some, or all, of that individual’s cells. This triple copy is sometimes called trisomy 21 [9]. The altered number of chromosomes leads to common physical features in the DS population, such as:

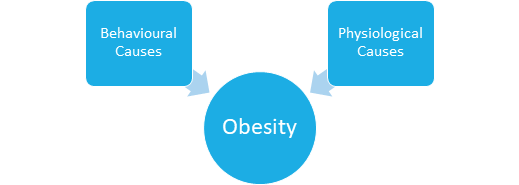

DS itself is not a medical condition and is simply a common variation in the human form. However, there are many medical conditions that people with DS frequently experience. These include:

- Learning difficulties

- Poor cardiac health

- Thyroid dysfunction

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Digestive problems

- Low bone density

- Hearing and Vision loss

- Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

- Depression

- Leukaemia [11][12][13]

| REMEMBER: Stay positive! Everybody is unique. These conditions are common in DS but are only possibilities, not inevitabilities. |

|---|

Though there are many similarities across the DS population, there is great variation in the syndrome. There are three types of DS, each with its own set of challenges and individual variation. The three types of DS are Trisomy 21, Translocation and Mosaicism. Further information on the differences between categories can be found here[14].

Whichever the type, persons with DS typically have poorer overall health at a young age and exhibit a greater loss of health, mobility, and increased secondary complications as they age when compared to their non-DS counterparts [15][16]. As a result, persons with DS and their families frequently access health services, especially physiotherapy.

What is Physiotherapy?[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is a science-based profession that considers all aspects of the person when approaching their health and wellbeing. Through movement and exercise, manual therapy, and education physiotherapists aim to empower people to take charge of their own health and participate in their treatment. The profession assists individuals with injury or disability to develop to their fullest potential and live as independently as possible [17].

Physiotherapists are commonly consulted to educate individuals and their families as well as provide input on health promotion and long-term condition management [18]. As many treatments often require on going maintenance, physiotherapists have become increasingly reliant on family members to support and implement home treatment plans in an attempt to encourage self-management [19]. Due to the variation in all people and across Down syndrome cases, no one physiotherapy intervention can be prescribed. Interventions are based on the individual’s physical and intellectual needs, as well as his or her personal strengths and limitations [12]. Some of the common issues that physiotherapists will address are:

- Delayed developmental milestones

- Balance issues

- Decreased strength

- Reduced levels of physical activity

- Issues with sensation

- Reduced mental health and emotional wellbeing

- High chance of Alzheimer’s disease

Developmental Milestones[edit | edit source]

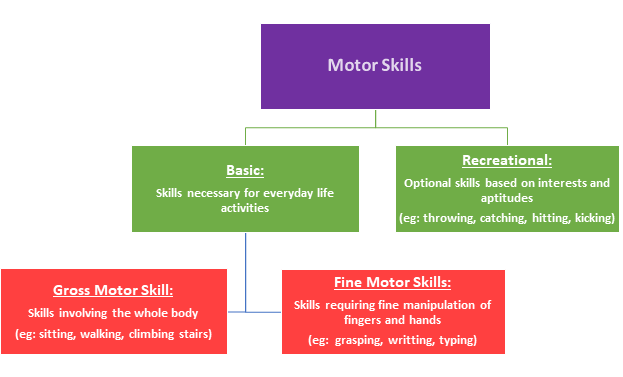

From the time a child is born, they are growing and learning. Each person develops at their own pace. However, some skills are expected to be mastered by a specific age. These are called developmental milestones. Milestones can be physical achievements, language related, or social accomplishments. As physiotherapists, we typically focus on motor skills [13].

The ability to move is essential to human life and development. All children begin developing a wide range of movement skills, or motor skills, starting at birth. These motor skills are wide ranging and often broken down into the sub sections below:

Motor skills are key for physical function, but also impact cognitive development.

- Reaching and grasping allows a child to explore the characteristics of objects in his or her physical world.

- Sitting promotes the use of arms and hands for playing.

- Walking allows a child to explore the world more effectively than crawling.

- Independent movement increases opportunities for social interaction which promotes language learning [1][20].

What is the Problem?[edit | edit source]

Persons with DS will generally achieve all the same basic motor skills necessary for everyday living and personal independence, however it may be at a later age and with less refinement compared to those without DS [21]. Some adjusted milestones for DS are available below:

For more in depth developmental milestone charts, please see here[23], and if you would like further description of milestones or to track your child’s progress at home, please see the checklist provided here[20]. While these milestones are generally agreed upon, studies targeting developmental milestones tend to only examine a small number of people. This makes the information less representative of the entire DS population. Also, researchers commonly compare people with DS to their non-DS counterparts of the same age. This is an invalid comparison, and it would be more correct to compare children with DS to non-DS individuals of the same mental age. Despite these limitations, the above listed milestones are widely used and considered accurate [24].

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

Physical characteristics of the child with DS such as low muscle tone, loose joints and decreased strength may limit the speed of mastery or alter the form of the developmental milestone. Persons with DS generally naturally overcome these challenges through perseverance [1].

The goal of physiotherapy is not to ‘speed up’ the rate of development. It is simply to facilitate the development of optimal movement patterns. Depending upon capabilities and adaptations made, physical compensations such as pain or inefficient walking patterns may occur. Physiotherapists are here to help with that! When considering motor skills in DS, the goal of a physiotherapist is to provide the building blocks to develop a solid physical foundation for movement and exercise that your family member can build on for the rest of their life.

Physiotherapy sessions focusing on developmental milestones will be specifically tailored to your child’s current level of development. The physiotherapist will observe your child’s abilities and determine what skills should be learned next. As each person is different, skills will be taught in the way your child learns best. It is common for tasks to be broken into smaller parts and practiced using different methods based on individual learning styles and physical make up.

What Can You Do?[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists will often get family members involved with treatment. Practice at home is essential for mastery, and your participation is key. The physiotherapist will teach you how to:

- Use your child’s interests to encourage new skill development

- Build on already mastered skills

- Focus on what your child is willing to learn

- Practice often

- Be patient

| REMEMBER: When thinking about developmental milestones, the journey to get there may be different, but the destination is the same! |

Balance and Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

As mentioned above, it is common for children with DS to be delayed in reaching common milestones such as sitting independently, standing and walking. One of the contributing factors to the delay of these specific milestones is poor balance. It is well known that persons with DS are often considered floppy, clumsy, uncoordinated and have awkward movement patterns due to balance issues. These balance challenges often follow the child into their teen years and sometimes into adulthood [25]. While impaired balance is difficult on its own, it may also impact development of other motor abilities and cognitive development. Being able to maintain balance allows for exploration, social interaction and overall freedom [26]. This highlights the importance of physiotherapy involvement in the child’s life so that the issue can be addressed.

What is the Problem?[edit | edit source]

- Loose Ligaments: Persons with DS have elastic/loose joints, allowing for a large range of movement. This may lead to joints being less stable and difficult to control, causing unbalanced behaviours.

- Low Muscle Tone: A common symptom of DS is a ‘floppy’ appearance, with little activity in the muscles at rest, impacting stationary balance. Floppiness does improve over time but can influence balance greatly in early years.

- Slow Reaction Times/Movement Times: Persons with DS often are slower to react and move than their non-DS peers. This means that even if the person is aware that they are unsteady, it will take a longer time to react to this feeling, and once it is understood, the corrective movement will also be delayed. Both of these aspects add a challenge to balance.

- Differences in Brain Size: Persons with DS typically have smaller cerebellums, which is a part of the brain that contributes to the control of balance. The small size impacts its function, limiting balance reflexes, and causing blurry vision when completing tasks at high speed. Other parts of the brain are also smaller, creating issues with voluntary activities, walking technique and coordination.

- Decreased Postural Control: Typical posture in a person with DS is hunched over, with a rounded neck, which prevents the head and body from sitting over the pelvis. Posture is impacted by inaccurate messages being sent to the brain from the body’s sensory system. This leaves people with DS less capable of adapting or making anticipatory adjustments to changing environments [26][27][28].

| REMEMBER: If you notice these qualities, do not worry. This is to be expected and can be improved upon with practice and patience! |

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

There are a wide range of physiotherapy interventions that can help your family member improve their balance. Some of them have been used for many years, while others are still developing and being introduced.

Some common traditional physiotherapy interventions to improve balance in persons with DS are:

- Stability Exercise (examples available here[30])

- Corrective positioning (examples available here[31])

- Stair climbing

- Yoga

- Hydrotherapy [32][26]

Some new emerging physiotherapy interventions being used to improve balance are:

- Hippotherapy

- Treadmill training

- Two-wheel bicycle training

- Tummy Time

- Perceptual-motor therapy

- Sensory integration training

These emerging physiotherapy techniques will all be discussed later!

What Can You Do to Help?[edit | edit source]

- Practice Makes Perfect: As with everything in life, practice will improve performance. While it often takes more practice to improve performance of balance in a child with DS, it is possible to increase both speed and accuracy of movement.

- Encourage Independent Movement: When a person actively initiates a movement, the brain learns how to control the area being moved. This improves coordination and task performance.

- Follow Individual Interests: Your child is more likely to eagerly participate if the activity is one that is enjoyed. Try incorporating balance training into sports and games.

- The Earlier the Better: Starting balance practice early in a child’s life will allow for greater amount of learning time and increase muscle strength at a young age.

- It’s Never Too Late: Though it is harder to correct learned bad habits, practice at any time is helpful. It is never too late to start.

| FUN FACT: Individuals with DS are more commonly visual learners. This means that they learn better by watching others or copying what they can see rather than responding to verbal instruction. Copy cat is a great game to help teach your child new tasks [33]! |

Strength[edit | edit source]

Individuals with Down Syndrome typically exhibit 40-50 percent less strength than individuals without DS, according to the American College of Sports Medicine.

Children with DS usually suffer from overall muscle weakness, slower postural reactions, and response time, in addition to hyper flexible joints[34]. Adolescents with DS do not demonstrate the physiological increase in muscle strength as that typically occurs at 14 years of age[35], therefore meaning that preserving muscle strength in children with DS at a satisfactory level is necessary to help them gain the most from the activities of daily life.

What is the Problem?[edit | edit source]

The presence of hypotonicity (low tone), joint laxity, and decreased muscle strength will cause excessive wear and tear on the joints over time. Adults with DS develop earlier musculoskeletal changes[36]. This means that muscle strength is an important element to maintain throughout the milestones of an individual with DS.

Children with DS are commonly more sedentary and less physically active than their non-DS counterparts, they are at increased danger of secondary health conditions, including type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis[37]. With this being said strength, especially to lower-extremity muscles in children with DS has a central significance to their general health and daily activity performance ability[38].

Interventions to improve strength in DS individuals of all ages are promoted as preventative care to decrease the wear and tear on joints. Training includes endurance training which involves large group of muscles working at moderate intensity for a more extended period, and strength training which involves small group of muscles working for short period with three sets for eight repetitions. Strength training was shown to be equally as effective as endurance training on exercise capacity and health quality[39].

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

The following section will try to inform you of a quick overview of the different strength training DS-related studies and interventions that may help those that you care for.

It has been shown in a case study with a young girl living with DS [40] that a home exercise program can help to improve cardiovascular endurance as well as produce strength improvements in the trunk muscles and upper and lower limbs. The same study showed that the subject, although not losing weight, didn’t gain weight. It is well documented that those with DS are more prone to weight gain. If you are concerned about the individual that you care for then contact their GP for advice and possible referral onto Physiotherapy for advice on training programs.

A study by the American College of Sports Medicine contained 10-week strength training program yielded significant gains for 12 participants, who performed six exercises (three sets of 10 repetitions, twice weekly). Strength improved dramatically—42 percent averaged over the three upper-body exercises and 90 percent averaged over the three lower-body exercises. Participants were seven women and five men ranging from about 18 to 36 years of age.

These studies as well as multiple others show that strength training is an effective method of improving strength and also one of the main findings of the study was that the strength training helped improve the individuals’ functional abilities, such as standing from sitting in a chair and ascending and descending steps.

Exercising also releases endorphins which make the person exercising feel better and happier so it can be a great mood booster also!

Any training programs should be done with the appropriate technique, it is heavily suggested that you consult professionals before attempting to begin one to check that is appropriate for those in your care.

Professionals and trainers can give tailored exercise programs which take into account your access to facilities and time scales to optimise the time taken to exercise!

They will also be able to provide coaching to achieve the best techniques and minimise risk of injury.

Common Concerns/What Can You Do to Help?

One of the more common concerns for parents and carers alike is that the person they care for isn’t as able to keep up with their peers due to different rates of development. This can be because you are worried on their behalf that their self-esteem is being affected.

Some helpful tips to help you deal with this are:

- Telling your son or daughter or person you care for about Down’s syndrome if you haven’t already. Make it simple and concrete and be realistic, but emphasise that they are more than Down’s syndrome. Though they may struggle with some things, they are a unique person with their own talents, strengths and personality.

- Your son or daughter may be focusing on what they can’t do. Point out the things they can do rather than the areas they find difficult.

- Support your son or daughter to take as much control over their own life as possible. Help them make as many of their own choices and decisions as they can.

- Encourage friendships, independence and social interaction with people their own age.

- Support your son or daughter to develop friendships with peers with learning disabilities and without learning disabilities. Having a mixture of friendships, including with people with learning disabilities, can help your son or daughter accept and feel happier with who they are. [41]

For more advice if you have large concerns with the self-esteem of those that you care for you can call the DSA Helpline on 0333 1212 300.

Another concern may be that the person under your care isn’t receiving the support that you feel they require. If this relates to your current position then contact your family members GP for further guidance and a potential referral.

Reduced Levels of Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

The evidence for physical activity levels in people with Down Syndrome is conflicting, with most depicting a highly sedentary lifestyle, where people with Down syndrome are not achieving the recommended guidelines for physical activity levels [42][43]. As well as this, age related declines in physical activity levels have also been identified in the Down syndrome population [42][44][45]), demonstrating that this is a lifelong issue that must be highlighted.

| FUN FACT: Did you know that the daily recommended levels of physical activity for children is at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity activity? Similarly, adults should participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity each week, including at least two strength session in the week [46][47]. Although people with Down syndrome may have decreased capacity for exercise compared to their peers without disability for lots of reasons, the guidelines clearly state that children with disabilities should meet the recommended guidelines or do as much physical activity as they are physically able to do[48]. |

Take a moment to consider how active your child has been over the past week. Do you think they are achieving their recommended daily activity levels? If yes, then great! However, if not, take the time now to try think of why this is happening. Are there specific reasons that you can identify from daily life which are stopping your child from being physically active?

Possible barriers which have previously been identified by parents as contributors to reduced participation in physical activity include behavioural characteristics of the individual with Down syndrome, alongside a lack of accessible programs and prioritisation of competing family responsibilities[49].

What is the Problem?[edit | edit source]

Individuals with Down syndrome have been found to have substantially higher rates of obesity compared to the general population[50]. Often occurring early on in childhood, obesity was found to remain stable from childhood into adulthood, with slight increases after puberty[51]. Obesity, now recognized as a major health risk for people with Down syndrome[52], increases the chance for the development of other health problems such as diabetes, increased blood pressure, dyslipidaemia, early markers of cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, breathing difficulties with worsening of sleep apnea and psychological effects including reduced quality of life[46][53].

The causes of obesity in the Down syndrome population can be divided into physiological causes and behavioural causes. Physiological causes may include conditions such as hypothyroidism, decreased metabolic rate, increased leptin levels (leptin is a hormone which helps regulate food intake by stimulating satiety), short stature and low levels of lean body mass[53]. Behavioural tendencies such as negativity and inattention behaviour may lead to becoming barriers that prevent important and necessary dietary and lifestyle changes to occur[53].

Aerobic fitness in both youth and adults with Down syndrome is reduced compared to their peers[54][55], with studies finding adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome having comparable aerobic fitness to old adults (60years +) with no disabilities but with heart disease[55]. As well as aerobic abilities, reduced muscular strength and reduced bone mineral density levels by 26% compared to peers have been identified in the Down syndrome population[56].

How Can Being Physically Active Help?[edit | edit source]

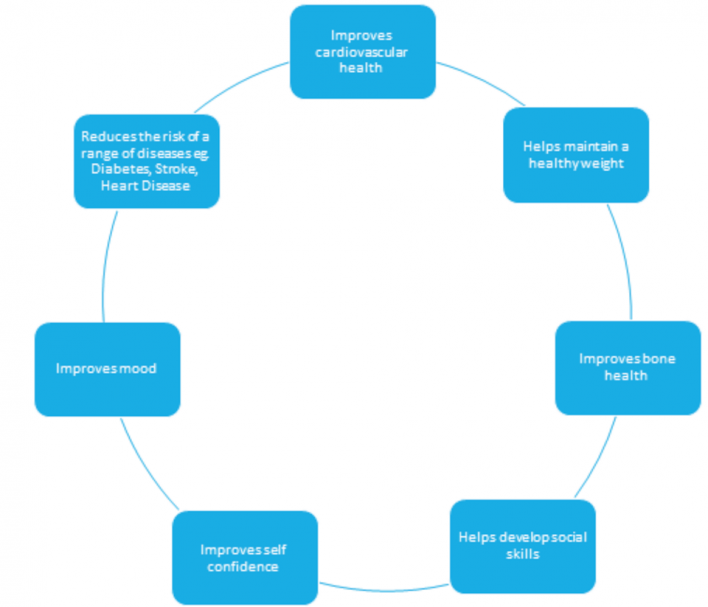

Overall, strong evidence suggests that regular and adequate physical activity can lead to numerous health benefits. Can you think of any? See how many you can come up with before you check out the picture below!

Physical activity participation has a really positive impact on people’s health, including the ability to improve cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal and psychosocial health profiles in people with Down syndrome[57].

As previously acknowledged in the Developmental Milestones section of this Physiopedia Page, onset of independent walking in children with Down syndrome occurs roughly 1 year later in comparison to children with typical development[58]. It is thought that perhaps low levels of physical activity during infancy may contribute to this[59] as earlier walking onset has been observed in infants with Down syndrome who performed greater amounts of high intensity activity at ~ 1 year of age[60]. Changes to physical activity levels in infants with Down syndrome has been suggested to be associated with their motor development, encouraging the importance of early interventions[59].

Increased physical activity levels have been found to reduce body fat percentage in children with Down syndrome[61]. A year after learning to ride a two wheeled bicycle, a group of children with Down syndrome had on average, 6% less body fat and were more physically active then their control peers. Following a 12 week training programme consisting of 30 minute cardiovascular exercise (using stepper machines, stationary bikes, crosstrainers and treadmills) and 15 minutes of strength exercises, 3 times a week, adults with Down syndrome had significant improvements in their cardiovascular fitness and muscular strength, with some reductions in body weight[62]. After completing a 12 week programme of either cardiovascular training 3 times a week or resistance training 3 times a week, young adults with Down syndrome experienced significant reductions in heart rates during the middle stages of max exercise testing, suggesting that the heart had become more efficient from being physically active[63]. Benefits to psychosocial factors have also been experienced following physical activity participation in people with Down syndrome. Following 12 weeks of cardiovascular and resistance training, combined with health education, significant improvements in life satisfaction and attitudes towards physical activity as well as lower depression levels, were recorded[64].

Alongside these health benefits, other reasons physical activity is so important for people with Down syndrome are it will help:

- Develop physical and social skills

- Establish a regular routine around being physically active, leading to better habits in the future

- Prevents secondary conditions associated with having Down syndrome including diabetes, osteoporosis and dementia[65]

From the evidence, it is clear that physical activity is integral to a person with Down syndrome’s health, fitness and wellbeing[48].If you feel unsure about what kind of activities to encourage your child to take part in, or would like to know what kind of physical activity groups are out there, then hopefully this next section will provide you with some useful information!

Interventions to improve physical activity levels[edit | edit source]

There are increasingly more opportunities and ways to help improve the physical activity levels of the person with Down syndrome in your life. Previous group interview sessions with parents have highlighted the need for information on physical activity interventions to be available to them, which should include a range of individual activities that would interest the child with Down syndrome and group activities for the family[66]. We hope that this section will achieve these goals.

According to the World Health Organisation, the recommended physical activity requirements for children as previously mentioned, is at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity daily physical activity.

| Moderate Activity | Vigorous Activity: | |

|---|---|---|

| Aim | Increase heart rate and breathing and cause a light sweat | Make the heart and lungs work harder than moderate intensity activity |

| Example |

|

|

Evidence is also growing to support other fun and creative ways for your child to be physically active, including:

- Treadmill Training

- Two Wheeled Bicycle Riding

- Therapeutic Horseback Riding (Hippotherapy)

Structured accessible programs that make adaptations for children with DS have been identified as key to facilitating participation in physical activity[49]. As well as that, it has been recommended that introducing diverse and interesting physical activity programmes which avoid over complicated tasks, may be more enjoyable for people with Down syndrome[67]. Scroll to the bottom of this page to find examples of these programs in the Resources section!

| REMEMBER: Physical activity and exercise are specialist areas of Physiotherapy. If you have any questions or are still unsure, speak to your local Physiotherapist and they will be able to help your child by identifying the most suitable methods of physical activity or exercise for them! |

Common Worries for Parents- Can You Relate?[edit | edit source]

If you are worried and feel uncertain about anything you have read, don’t be, for you are not alone!

Some of the most common worries reported by parents of people with Down syndrome, surrounding a discussion on physical activity participation levels include:

- They fear that their child will not remain active in the future

- They want to help their child be more active however feel they don’t have enough time in the day as well as manage their other family needs

- They find it difficult to motivate their child to be physically active

- They want to help their child avoid obesity in later life but are unsure how

- They wish they provided earlier support and more opportunities to their child to learn sporting skills

- They feel they do not receive enough information to know how to make the best decisions on what activities are best for their child

- They worry about the cost of organised programs and not being able to afford keeping their child enrolled in them [66][45]

What Can You Do to Help?[edit | edit source]

“There may still be a need to raise expectations of what young people with Down syndrome can achieve among parents, professionals and the wider community”[45]

One of the most important facilitators identified for improving physical activity participation levels of people with Down syndrome is the support and motivation they receive from their family and carers[49]. When interviewed, parents felt their child was more likely to be active when the physical activity was enjoyable and included being with friends or their siblings[45][66]. Introducing physical activities into your child’s routine and encouraging a familiarity with them may also help facilitate improved participation[68]. Encouraging your child to keep an activity or exercise log and organising a routine check of it alongside providing motivation, has previously been a suggested as a helpful method to increase physical activity participation[66].

Other tips to help encourage your child to be physically active include:

- Choose an activity that your child will enjoy or ask your child what activity THEY want to do

- Encourage childhood games that are traditional and active such as hop scotch, hide and seek, obstacle courses

- Use simple way to get your child to choose more physically active options in daily life such as walking to school (if feasible), taking the stairs option instead of the lift, walking your family dog

- Keep things simple; running, jumping, dancing are great physical activities to build your child’s fitness and there are no cost requirements, only for you to join in yourself and get fit too!!

- Give your child lots of positive and encouraging feedback [48]

Take a look at the Resources section which highlights information on websites and active groups that can provide fun and enjoyable opportunities for your child to partake in sport and physical activity. Make the leap, and contact someone from that list today! You never know, this might be one of the most simple but important impacts you have on your child’s future.

Sensation and Memory[edit | edit source]

People with Down syndrome can present with sensory delays as well delays in cognitive, physical, motor and social development[69]. Being unable to process sensory information from the environment can be both frustrating and challenging, often leading to inappropriate behaviour as a response[70]. As humans, we also use sensory information to gain experience, learn and interact with the world. When sensory feedback is limited, it can impact progress in other areas such as motor development[69].

Do any of these behaviours seem familiar? Sensory difficulties can impact your child’s behaviour, the way they can interact with people and objects around them and development of their movement and motor skills [70].

Another challenge the brain can face for those with Down syndrome is Alzheimer’s which is the most common cause of dementia. These two terms are commonly used interchangeably but are in fact different diseases. Dementia typically involves symptoms including memory loss, difficulties with thinking, problem-solving and/or language and these occur due to damage to the brain such as that caused by Alzheimer’s.

As stated above, having Down syndrome does not mean you will get Alzheimer’s! Current estimates state that roughly 50% of people with Down syndrome will develop dementia due to Alzheimer’s as they age and symptoms only begin to show in the individuals 50s or 60s[72].

There are lots of articles and pages discussing the link between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s which can be tricky to understand and can often sound scary, especially to a parent or loved one of someone with Down syndrome. This link here[73] is a guidebook which covers the general process of ageing for persons with DS, including some information on Alzheimer’s (pgs 16-24) which you may find less intimidating but still informative!

What is the Problem?[edit | edit source]

Sensation

Information from the environment is processed by our brain and can be interpreted as things like sound, touch and movement. The brain then organizes this information before directing the body’s response. Typically, we are able to manage all this continuous processing without really having to think about it. People with Down syndrome aren’t always as able to sort through information and can quickly become overloaded and sensitive to stimuli (hyperesponsive) which causes the brain to ‘short-circuit’ or immune to it (hyporesponsive) where the brain fails to register input[74]. It’s important to understand that people can’t always be neatly categorised into one or the other and crossover does occur.

Hyperesponsive Behaviour

For example, most people enjoy a light touch from a loved one, whether a pat on the hand or a hair ruffle, a positive response is usually expected, particularly from children. However, some people with Down syndrome can register this as dangerous and so will scream or pull away – an over-reaction to me or you maybe but an appropriate response according to their brain. You could compare it to us walking down a scary street at night, our bodies would be on full alert. If we spent every day in this state of awareness, exploring our environment becomes difficult and without this exploration, it becomes challenging to learn from experiences which you cannot be an active part of[74].

Hyporesponsive Behaviour

An individual whose brain fails to register input usually bombards their sensory system, typically by constantly touching objects or falling repeatedly. They don’t usually respond to pain in a ‘typical’ manner, by crying or touching where the pain is and may bump into the same object over and over. If we were in a pitch-black room and told to find a way out, we would call on our other senses – touch and sound for example. People who are hyposensitive are continuously using their brain in this intense way in order to understand their environment [74].

Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s is a physical disease of the brain caused by build-up of a certain protein which forms plaques or tangles. As mentioned earlier people with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21 which carries a certain gene. This gene produces a specific protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP) which leads to the aforementioned plaques/tangles[76].

These plaques/tangles can cause a loss of connections between cells, leading to a loss in brain tissue. People with Alzheimer’s also have reduced amounts of certain chemicals in their brain which help to transmit signals in the brain which leads to less effective signal transmitting.

Some common symptoms of Alzheimer’s:

- Short-term memory loss

- Reduced interest in activities

- Social withdrawal

- Confusion and disorientation

- Increase in wandering

- Increased problems in unfamiliar places

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

- Sensory integration therapy (SIT) can help with numerous sensory deficits.

Although there is no specific physiotherapy treatment for Alzheimer’s, the guidebook previously mentioned discusses the link between Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s, the different stages, approaches to providing care and some tips on communication. You may also find the websites for the National Down syndrome Society and The Alzheimer’s Association helpful.

| REMEMBER: Therapies of any kind are not designed to ‘fix’ or ‘cure’ people. They are intended to help improve certain challenges a person might be facing by developing tools or skills required to achieve tasks as independently as possible! |

What Can You Do to Help?[edit | edit source]

If your child or loved one is receiving sensory therapy from a physiotherapist, it would be good to talk through some of the suggested ideas to check how appropriate they would be!

If you are short on time for whatever reason, here are some ideas for incorporating therapy into everyday activities:

- When brushing their teeth at night, try using a vibrating toothbrush if tolerated.

- Before taking them on errands such as to the hairdressers, try giving them some chewy sweets for the different texture.

- During meal prep or baking, let them mix the ingredients together, carry pots and pans or even tenderize your steak (with supervision of course)!

- When you go grocery shopping, allow them to push the trolley if able and help with packing and putting food away.

- During mealtimes, allow them to drink with a straw and try a weighted lap blanket or a big squishy cushion on their seat.

- If they still require your help bathing then try out different brushes, cloths and soaps. Use crazy soap or shaving foam to draw on the wall and when drying them, wrap them tight in a towel and apply pressure (a hug works well) if tolerated!

- During playtime try playing the ‘sandwich game’ – lie the child in between two pillows so they are effectively the sandwich filling and apply pressure on top to their liking (ask them harder or softer). Any home-made obstacle courses involving jumping, crawling, hopping etc... are usually beneficial[77].

| REMEMBER: If your loved one becomes distressed by any of these then stop immediately and change tactics! Try to be aware of their reaction and respect it, any indication of fear or distress is real for them even if it appears to be an over-reaction to us! |

Another idea is to create a ‘sensory corner’ which can be effective in reducing stress and produce a safe zone for some children. It can provide both stimulation for a hyporesponsive person and a safe retreat for a hyperesponsive person.

Making a sensory corner is nice and simple! Just block off a corner of a room and use soft furnishings with different textures. For example, use different carpets and seats, often a large beanbag can provide deep pressure which can have a calming effect and objects like lava lamps, or aquariums can feel relaxing. Other things like music and an optional sensory box filled with various objects that differ in texture and weight can be useful. Every person is unique, and you can explore and have fun finding out what kind of objects and textures work for you and your loved one! An example of a sensory room and sensory box are depicted below:

Click here for more sensory ideas you can try with your child!

Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing[edit | edit source]

It is not uncommon for individuals with Down syndrome to experience challenges with emotional behaviours and mental health. Children with Down syndrome may have difficulties with communication skills, problem solving abilities, inattentiveness and hyperactive behaviours. Adolescents may be susceptible to social withdrawal, reduced coping skills, depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behaviours and sleep difficulties. Adults wtih DS may have similar experiences as adolescents, with further complications of dementia later in life[78].

Here are some more details to help you recognise the signs of different mental health conditions. After gaining a good understanding of these behaviours, you will be more familiar with approaches to assist your family member with Down syndrome to cope with these challenges in positive ways.

Depression[edit | edit source]

Adolescents and adults, and sometimes children with Down syndrome may display depressive symptoms such as sadness, severe social withdrawal, or avoidance of activities that were previously enjoyable. These behaviours tend to be associated with an event that, to you, may seem like a normal life occurrence, but is perceived as a great stress to someone with Down syndrome. Such events may include the loss of a household pet, a friend or a sibling who moves away, an illness in the family, or the extended absence of a teacher. Individuals with Down syndrome can be particularly sensitive to changes in their environment and if they do not cope appropriately, this may cause significant psychological distress[76]. Challenges may arise including withdrawal from social and physical activities, which may prolong important development in these areas and impact quality of life. There are a variety of treatment options for depression, including counselling, identifying coping methods for stressful events, medications, and participation in exercise and enjoyable activities[79].

Anxiety[edit | edit source]

If your family member with Down syndrome experiences anxiety, they may display behaviours such as restlessness, panic, fidgeting or excessive worrying, which is often stimulated by transition to a new or unfamiliar situation or environment. For example, going from home to a different environment such as school, a disruption of a daily routine, or anticipation of a new event[80]. This may prove challenging when introducing new activities to individuals with DS so it is important to plan ahead and incorporate new activities gradually into a routine that they are happy with.

Routinised and Compulsive-like Behaviours[edit | edit source]

Children and adults with Down syndrome have a tendency to follow familiar routines which may appear repetitive, compulsive or ritualistic[1]. They may insist on undergoing the same household routines, require situations to be ‘just right’ and participate in the same activities. These behaviours are often performed to avoid feelings of anxiety[81]. It is important to introduce physical and social activities early in life so they become part of your child’s routine and encourages achievement developmental milestones. From there, creating coping strategies and planning ahead will ease your child with Down syndrome into trying new activities as they get older.

Hyperactive and Inattentive Behaviours[edit | edit source]

Children with Down syndrome may appear to be easily distracted, impulsive, frequently restless and on the go and they may have difficulty maintaining attention on tasks. This behaviour may persist into adulthood, however tends to diminish with age[82]. It often causes a barrier to participation in physical activities due to non-compliance and the need for increased supervision[49]. There are medications which are said to reduce these behaviours, however they often trigger adverse side effects. Instead, it can be beneficial to channel this hyperactive energy into participating in activities that your child enjoys, or find an activity that provides a calming effect.

Physiotherapy Interventions[edit | edit source]

Physical activity has demonstrated excellent benefits for the mental well-being of individuals with Down syndrome. The benefits include greater life satisfaction, reduced risk of depression, increased self-esteem, and improved social and behavioural skills[64][49]. Any activity which promotes social interaction and friendship further enhances mental and emotional well-being. Some interventions may include:

- Therapeutic Horseback Riding (Hippotherapy)

- Two wheeled bicycle training

- Sensory integration training

- Perceptual-motor therapy

- Hydrotherapy

- Yoga

What Can You Do to Help?[edit | edit source]

- Work with a professional that has experience with individuals with intellectual disabilities to develop a behaviour treatment plan. They can also refer you to interventions to address specific behaviours

- Take advantage of every opportunity you have to interact with others! While most people learn the majority of their social skills in school and work, people with Down syndrome can “make every contact count”. Whether it is in therapy, school, work or at home, the opportunity to learn is everywhere!

- Support groups and therapies are a fantastic way of hitting two bases at once; therapy and socialising.

- Develop a routine and stick to it. Try using visual schedules! This method uses pictures or books to help your family member prepare for upcoming events such as beginning a new school year, going to a friend’s party or moving into a new house.

- Plan for difficult situations. Try using social stories!

- Ensure to promote positive interactions and reduce the negative ones. Make time for fun every day!

- Always encourage positive behaviours and positive attitudes [1][79][83]

An example of a visual schedule. If you have time, you can sit down and make one together!

For further information on mental health and learning disabilities please click here[84], and for tips on improving the mental health of people with learning disabilities please click here[85]. Other useful links may be found at the end of this wiki.

Physiotherapy Approaches Explained[edit | edit source]

As stated above, not everyone with Down syndrome requires physiotherapy and as with most things in life, it depends on the individual and what they need. Although there is no standard treatment plan, effective physiotherapeutic management of Down syndrome typically involves a combination of sensory integration therapy, neurodevelopment treatment, perceptual-motor therapy and traditional strength and conditioning programs[41].

Traditional therapies for conditions involving difficulties with movements can be repetitive and lack variability[86]. People with Down syndrome often have a reduced attention span which makes engaging in any therapy challenging, especially when dealing with children[87]. By constantly introducing different textures, sounds, environments and movements we can make therapy more interesting and inclusive. Throught this page we have mentioned a few loss common techniques that a growing in popularity. We have described them below to help you better understand what to expect and familiarize yourself with!

Sensory Integration Therapy (SIT)[edit | edit source]

People with Down syndrome often struggle to process information from the environment (things like smell, touch and movement) in the same way we can and this is known as sensory integration dysfunction. SIT aims to recondition the relationship between the brain and environment, in particular by working on the vestibular, proprioceptive and tactile systems[88]. The video below explains these systems and why they are important in everyday life!

SIT involves a wide range of activities and equipment such as weighted vests, brushes, swings, balls, homemade obstacle courses [89] and even game consoles such as the Wii[86] which are all used to provide forms of sensory stimulation. This kind of interactive therapy has been shown to increase focus, reduce disruptive behaviours and improve high functioning tasks such as reading, writing and speech[88].

If SIT is recommended for your child, it is likely that an occupational therapist (OT) will also be involved. OTs are concerned with how people manage to do meaningful activities and can help by providing equipment which ultimately aims to promote independence.

Traditionally seen as more of an ‘OT thing’, the benefits of understanding how sensory-based issues can impact on motor performance can enhance our practice as physiotherapists, particularly when working with children. There is now a PT/SI special interest group which offers peer support and shared learning for physios wanting to gain more experience in SI and to promote the benefits of physios taking a larger role in SIT[90].

Neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT)[edit | edit source]

NDT is an approach which focuses on the quality of movement and coordination rather than individual muscle group function[91]. Therefore, NDT is most effective as an early intervention, before poor compensatory patterns of movement become habitual. As physiotherapists, we can use our hands both to prevent abnormal movement patterns and to facilitate more natural ones. This hands-on approach is achieved by the physio having several ‘key points of control’, usually at the head, shoulders, trunk and/or pelvis to guide and alter movement[91]. NDT is usually appropriate for people with Down syndrome as they often present with some neuromuscular dysfunction such as low tone (limbs and muscles which are floppier than normal) and reduced control of their limbs[86].

Although NDT will be different for every individual, a video with some examples of what a more hands-on therapy approach can look like is seen below.

Perceptual-motor therapy (PMT)[edit | edit source]

PMT incorporates activities which help to explore balance, coordination and body awareness and is not skills based. So, rather than being taught a certain skill, individuals are provided with an environment which they can use to explore what their bodies can do and how (see video below). (SOURCE?)

Two wheeled bicycle training[edit | edit source]

One type of exercise that is not only a way for your child to improve their physical activity levels, but also a way to enjoy themselves and socialise with other children more, is Two Wheeled Bicycle riding. The skill of bicycle riding is one that can be learned from a young age or later in life[42]. Studies have shown that people with Down Syndrome often have reduced physical activity levels[59], along with reduced sports participation. Assisted two wheeled bicycle riding has been shown to reduce sedentary time and increase time participating in moderate to vigorous activity[61]. As well as that, this skill has the potential to increase your child’s independence and autonomy, whilst helping to diminish their fears surrounding falling from a bike and getting hurt[61]. If you are searching for an activity for your family to do together, that has the potential to improve your child’s quality of life[92], then assisted two wheeled bicycle riding could be a great activity to try out!

Therapeutic Horseback Riding (Hippotherapy)[edit | edit source]

Do you wish to enrol your child in an activity that promotes friendship, fun and progresses confidence with movement skills? Therapeutic horseback riding is a strategy that uses a horse’s motion to promote training of muscle and balance skills required for everyday life activities[93]. While horse riding, your child will experience movements of their trunk, pelvis and hips, similar to those that would take place during normal walking[94]. Adapting to the horse’s rhythmic movements in different directions further enhances muscle contraction, postural control, weight shifting, and planning of movement patterns[95].

The overall benefits of therapeutic horseback riding includes advances in balance, muscle strength and coordination, trunk control, postural stability, and weight bearing abilities[93]. Learning new movement strategies through horse riding can also progress skills such as walking, running and jumping[95]. For more information, please see the video below

Treadmill Training[edit | edit source]

"The key is if we can get them to walk earlier and better then they can explore their environment earlier and when you start to explore, you learn about the world around you" [96]

Infants with typical development learn to walk independently at about 12 months of age. Babies with Down syndrome typically learn to take independent steps at 24-28 months. These are averages, and averages & developmental milestones are often fed to the parent of DS children like a ticking clock to race against. So before we delve into this topic, do not fear if your child is behind the curve, as everyone develops in their own unique way.

Getting your child walking is of importance as it allows them to interact with the world around them and it’s often a stepping stone to the development of other social, motor and cognitive skills. Developing walking can allow your child to engage in more enjoyable tasks, and the endurance achieved in doing so allows them to be active for longer periods of time! More skilled walking is less tiring for your child and could mean they have more energy to take on the rest of their day. Promoting independence through walking can also leave you with free hands and ultimately less work for you!

Research carried out in recent years has suggested that regular walking on a treadmill can significantly improve the walking ability of children with Down syndrome. Put simply, different research groups have used treadmill training, with varying degrees of speed, time length and frequency to see if there was an impact on walking.

One highly regarded study[96] investigated whether treadmill walking for 8 minutes a day, 5 days a week had an effect on walking development. They then compared the results to a group of children with DS who did not do treadmill walking. What they found was that the group who walked on the treadmill displayed better standing and walking than the group who didn’t.

Treadmill training lead to quicker learning of walking & standing was the main message from this study.

Have a look at the children’s development in the video below

What’s great about treadmill training is that it is carried out by you, in your own home. This allows you to work the walking practice around your busy schedule and to suit your child. It also allows for your input into your child’s development giving you the sense that it’s not all out of your hands!

Tummy Time[edit | edit source]

Infancy is the ideal time to start encouraging movement and motor skills. These skills promote interaction between the child and the environment which will improve cognition, language, social skills and independence. Due to the already high risk of developmental delays in infants with DS, this is an especially important area of focus[97].

Tummy Time is a simple physiotherapeutic intervention used for infants with DS. Parents are encouraged to position the child on his tummy in various positions for extended periods of time. Lying in this position has been found to be extremely beneficial, as it affords infants the chance to develop strength, balance and motor skills against gravity. When this technique is practiced, the infant often achieves motor milestones, such as rolling, sitting and crawling, and improved balance earlier in life. Infants who do not experience enough time on their belly have decreased ability to support their own head at 2 months of age and have further delayed developmental milestones[98]. Some of the possible positions are pictured and described below:

Tummy Time in non-DS children has been proven to be a positive contributor to mastering developmental milestones. This intervention has only recently been investigated specifically for children with DS. There are only a few research studies available, but results have been consistently positive. Tummy time should be started as early as possibly in infants with DS. When a child with DS begins this intervention within the first ten weeks of life, they experience levels of motor development similar to that of half the children without DS. This technique is easily started at birth and can be performed by parents or caregivers. It is the foundation to motor skill mastery in the first year of life and increases balance, strength and skill attainment as the child grows[97].

Further information on tummy time positions is available here[100].

How to Get Active in the U.K[edit | edit source]

This section includes information on popular programs that are accessible and enjoyable ways to help your child be active. As the authors of this information page are students from Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, it was decided that information on U.K based programmes with subdivisions of Scotland would be included as resources for our readers. It is recommended to readers outside of the U.K to contact their National Down Syndrome Association and find out what groups and programs are up and running in their vicinity.

Down’s Syndrome Association[edit | edit source]

The DSA has a really great website up and running where you will be able to find endless helpful information surrounding tips and ways to help your child become more physically active. One way they have achieved this is through the provision of an easy read exercise routine that can help your child get started! A link to their website is available here.

DSActive – Activities for people with Down Syndrome[edit | edit source]

This sports programme was set up in response to the awareness of the sedentary lifestyles of many children and adults with Down Syndrome and is administrated by the Down’s Syndrome Association (DSA). It currently has over 40 football sessions and 20 tennis programmes run through the UK. If you are looking for an accessible and successful way for encouraging your child to take part in sports and improve not only their physical fitness, but also their social and emotional development, check this group ou in the video below, or visit their website here.

Down Syndrome Swimming Great Britain[edit | edit source]

This organisation was created to provide opportunities for people with Down Syndrome to complete at a World Class level. If your child enjoys swimming, or if they just want to give it a try and see, why not get in touch with the organisers and find out where your local leisure pool is situated? Click here to go to their website.

Riding for the Disabled Association[edit | edit source]

The Riding for the Disabled Association (RDA) is a UK charity which provides opportunities for people of various ages and abilities to participate in horse riding therapy, led by health professionals and volunteers. RDA research has shown that after 12 weeks, riders demonstrate great improvements in physical abilities, self-confidence, communication and relationship building skills[101]. Often the riding sessions provided are free and just require you to fill out an application form. You can visit the RDA website here for more information on how to enrol your child in therapeutic horseback riding and the many locations across the UK where you can do so.

Examples of Other Local Scotland Groups and Programs:[edit | edit source]

Information on Local Scotland groups set up for people with Down Syndrome in order to improve physical activity levels, can be found on the Down’s Syndrome Scotland website or by just following the link here.

Some examples include:

- Boogie Brunch – A popular Edinburgh fortnightly group which focuses on music and dancing, with the occasion social cinema or bowling outing!

- Magic Stars – A Lothian group open to children ages 12 years +, which focuses on all things healthy living, healthy eating and exercise

- Swimming Groups - There are numerous swimming groups for your child to join in the West of Scotland, and there is a recommended contact on the above website if you are interested and would like more information

- Fabb Scotland- This organisation enables children and young people with disabilities to access sporting, leisure, social activities as well as outdoor adventures. Visit their website here.

- The Yard- The Yard is an award-winning charity running adventure play services for disabled children, young people and their families. In the east of Scotland, they offer disabled children and their siblings the chance to experience fun, adventurous indoor and outdoor play in a supported environment. Promoting physical development and social interactions, The Yard offers emotional as well as practical support for families. See their website for further info here.

Other Challenges for Persons With Down syndrome[edit | edit source]

Reduced Social Interaction[edit | edit source]

Although not a Physiotherapy issue as such, it’s worth mentioning that the social lives of persons with Down syndrome can be very different to others.

Managing many of the physiotherapy issues mentioned above requires time and effort spent in therapy and carrying out home practice.

As a result, persons with DS often find themselves meeting and interacting with their peers less. This is something to consider as meeting others is important for developing social and life skills.

Social skills which can differ in people with DS include:

- Social understanding and empathy

- Friendship making

- Play and leisure skills

- Personal and social independence

- Socially appropriate behaviour

Transition From Child to Adult Services[edit | edit source]

Becoming an adult can be confusing and difficult for everyone, especially people with caring needs or intellectual disabilities (ID). There are several pieces of legislation set out by the UK government which aim to address the transition period for people with ID moving from child to adult services;

The Road Ahead Project was commissioned by the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) in order to explore what information people with ID and their parents might need during this transition period[102].

It was found that the most important and relevant information sought was:

- Their role within the transition process including their rights and entitlements.

- The local situation – support and resources available.

- The young person’s rights and responsibilities as an adult including information on self-advocacy, empowerment and keeping safe.

- All of the choices and changes available.

The Education Act[103] states that at the time of transition, healthcare professionals have several responsibilities;

- Provision of written advice including details about services likely to be required in the near future once they have left child services.

- Discussion of transfer to adult services with the individual, their family and GP.

- Facilitation of any necessary referrals.

- Attend individual’s annual review meetings from year 9 onwards.

Does This Make the Transition Perfect?[edit | edit source]

The short answer is no!

Despite numerous government legislations and guidance, there continues to be a marked variation in the arrangements available for the transition from child to adult services, with five different approaches to transition commonly being used[104]. There are also many problems with current transitions:

- One fifth of children were left without transition plans.

- Half had little to no involvement with their own plans.

- The quality of the transition plan varies hugely.

- Those who did receive a transition plan found it made little to no difference in what happened after leaving school.

- There were very few post-school options available in terms of housing and employment.

- There was a distinct lack of easily accessible information for parents and their children.[105]

What is Being Done? [106][edit | edit source]

Collaboration

- Between Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and adult intellectual disability services.

More training

- Better education for staff in both adult and child services.

- Improved knowledge of legal changes associated with becoming an adult

- Improved knowledge regarding other agencies to refer to and to make the person and their family aware of.

Better integration between services

- Different services have differences in their structures and philosophies – if there was more integration between services and increased awareness of each other’s role, a more uniform and continuous service could be provided.

Still Worried?[edit | edit source]

It’s perfectly natural to have concerns, everyone does!

The information below has been pulled from a recent study[107] investigating what parents of children with learning disabilities thought after professional intervention, its impact on their children and how it affected their lives overall.

Parents reported they found their child more willing to try new activities, socialize with others and were more able to express their emotions and desires. This study also highlighted some parent’s initial concerns and why they first started seeking sensory therapy for their children, some of which are listed below:

“Bonnie worried about her daughter’s behaviour on the school playground. Her daughter would be pacing the playground by herself rather than playing with other children.”

"Darcy sought assistance because she had a big “teddy bear” kind of kid who was hurting other children. She was concerned about his relationships with peers.”

“Another mother, Janet, worried that her son "was just so incredibly far behind his classmates. He was so taken up with the basic tasks that he couldn’t get on to doing anything fun.”"

Interestingly, parents felt professional input allowed them to have an increased understanding of how various difficulties affected their children. It was reported that parents felt more accepting of their children and any inappropriate behaviour which they believed led to a noticeably improved sense of self-worth in their children:

"It made us less frantic about trying to fit into mould of a child that doesn’t exist. And it made us all more accepting of her behaviors....It helped us try to work with her needs and not just our needs for her....I began to understand her needs. That was important. Psychologically she was getting hurt because she was thinking she was a bad person....My child was incredibly happier as a result, and that was a really important measurement for me."

What About You?![edit | edit source]

Down syndrome can be challenging for the individual, but also for the family. It is common for family members of persons with DS to:

- Feel increased levels of stress

- Experience lower levels of well being

- Exhibit mild depressive symptoms

- Have decreased confidence in raising their child

- Think about their child’s social acceptability

- Worry about their marriage or their other children[108]

| REMEMBER: These feelings are completely normal and felt by members of many families with a member who has DS. You are not alone in your feelings! |

Much research has been done on family dynamics and though results are often unclear, recent investigation is revealing that the increased levels of stress and decreased levels of well-being are evident in parents with a child who has DS for a variety of reasons. Demanding parenting roles, concerns over your family members social acceptability and decreased confidence in parenting skills are just a few contributors to high stress levels in parents of persons with DS[109]. You may feel as though you can handle stress, but it can often lead to poorer physical health and depression, which has shown to have detrimental effects on both individuals and families.

For this reason, it is important for you and your other family members to take time to focus on yourself. As a caregiver, if you are stressed, worried or unsatisfied, it can negatively impact your health, your child’s health and your family unit. Never forget that you are important too!

Taking time for yourself will improve both your personal mental health and your families’ overall well being. Though these small things may seem insignificant they can have a dramatic effect on how you feel and the cohesiveness of your family unit[110].

Ways you can destress and take time for yourself:

- Keep up with activities you enjoy

- Take a night off

- Plan occasional date night

- Involve the whole family in daily chores

- ASK FOR HELP and accept help when it is offered

This will lessen the stress felt by each member of your family. It has also been shown to increase experience satisfaction in your parenting role your which decreases stress levels. Keeping a strong bond with your spouse or main support leads to less depressive symptoms and increased parental confidence[111].

So ,while your focus might be on supporting your loved one with DS to realise their full potential, you too must strive to live an enriched life!

Luckily there is a host of services available to help you achieve this! Support for you can come in many forms. Common forms offered are respite care for your loved one, skills workshops to make caring less strenuous or support groups for you to exchange ideas with others.

A great place to start looking is the Carers UK and Carers Trust websites. Both agencies strive to make life better for carers by offering help and expert guidance on finances & benefits, careers, health, relationships and technology. They offer:

- Telephone advice services offering guidance on financial and benefits paperwork allowing you to navigate your way through the maze with more ease.

- Support groups and meet-ups organised by local ambassadors and volunteers.

- The carers club card offers discounts on high street retailers.

- Advice and some financial support for organising respite care for you and holiday destinations which cater for persons with DS.

The Down Syndrome Association and Down Syndrome Scotland also offer services specific to carers of persons with DS. They offer parents workshops on effective communication, behaviour analysis, manual handling and a host of useful topics. Again these workshops offer a great opportunity to meet other carers and parents of persons with DS.

Check out the Downs Syndrome organisation map of local support groups here or Down Syndrome Scotland here.

Other resources include:

Exceptional Parents: An organization that publishes a monthly magazine and maintains online resources to provide practical advice, emotional support and up-to-date information to the parents of special needs children

Parenting Special Needs: Another organisation that publishes an online magazine designed to bring inspiration and information the parents of children with special needs

Down syndrome in the Media[edit | edit source]

Representation of persons with DS in the media is vital as it give the public an insight into a community of people that they might not be familiar with. It also allows individuals with DS to be represented as individuals rather than groups or a stereotype. Unfortunately persons with DS are hugely under-represented by the media

The BBC’s video Things People with Downs-Syndrome are Tired of Hearing is an excellent example of how the media can challenge what the public view of persons with DS is. It highlighted that although attitudes are changing, persons with DS still find themselves subject to some really patronising questions!! Bekki Maddox, a contributor to the video said: "If it helps even one person to change their perception of DS then we have done our job."

The Don't Screen Us Out campaign was launched in response to the UK governments plans to offer increasingly advanced screening tools to mothers to screen for DS. The latest figures tell us that 90% of children who are diagnosed with DS prenatally are aborted[113]. The group suggest that with the implementation of a new non-invasive prenatal test, the number of children born with DS will decrease by 13%.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

A diagnosis of DS can be a worrisome time for families. It is often unexpected and can be difficult to modify your expectations for your child. In this wiki we consolidated available information into one resource to facilitate learning.

The first obstacle tackled was expectation. Differences between DS populations and non-DS populations were discussed in terms of motor skills, and common misconceptions about DS were addressed. We hope this has allowed you to envision a realistic future for your family.

We wanted to emphasise the large role that physiotherapy has to play in the care and management over the lifespan of a person with Down syndrome. From birth, physiotherapy interventions aim to aid in development and provide an essential foundation for the individual with DS to build upon. Whether it is assisting in learning skills for everyday life, or working through particular challenges, physiotherapy attempts to make life easier. As the individual grows, and new challenges arise, physiotherapists are available to provide advice and help you and your child overcome any problem that you may face. Some challenges discussed were balance, strength, levels of physical activity, sensory and memory difficulties and mood and mental health.

We also tried to provide you with a variety or resources throughout the wiki to aid allow you to investigate any specific areas of interest you may have.

Finally, we hope you have realised that you are important too. Though your child may require a significant amount of attention, it is vital that you look after your own mental and physical health as well. Numerous tips and support groups options have been provided.

Overall, the goal of this page was to enlighten you to the complexities of Down syndrome, inform you of the role of physiotherapy in managing these challenges, and help you understand your child’s potential. It is our hope that you feel encouraged, supported and confident in your ability to care for your family member with DS.

| ALWAYS REMEMBER: your child is special, you are not alone, and physiotherapists are here to help! |

Continued Learning[edit | edit source]

We realise that this resource was developed with a large emphasis on the role of physiotherapy in the management of Down syndrome. It is likely that you have other questions which have not been answered on this page. Below are links to external websites which we hope will aid in answering any lingering questions.

The Role of Speech and Language Therapists in Down Syndrome

Strategies to address challenging behaviour in young children with Down syndrome

Behaviour and Down syndrome: A practical guide for parents

Dads Appreciating Down Syndrome (D.A.D.S.)

MUMS: National Parent to Parent Network

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 National Down Syndrome Society. Down syndrome fact sheet. www.ndss.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NDSS-Fact-Sheet-Language-Guide-2015.pdf (accessed 14 March 2018).