Facial and Dental Injuries in Sports Medicine

Top Contributors - Caitlyn Yount, Temitope Olowoyeye, Josh Williams, Kyle Smith, Daniele Barilla, Kim Jackson, Mohit Chand, 127.0.0.1, Naomi O'Reilly, Brittany Wallace, WikiSysop, Claire Knott and Tony Lowe

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Injuries sustained while participating in sporting activities are due to either trauma or overuse of muscles or joints. Sports injury ranks among the major public health problems [1]and are a common complaint in the emergency department.[2]Various dental and facial injuries encountered during sports are; luxation injuries to tooth, avulsion, fracture of the facial bones, and concussion injuries.[3] Prevention of these injuries during sports is important.

Eye Injuries[edit | edit source]

Ocular injuries in sports are common and mostly preventable. Sports at high risk for eye injury include baseball, hockey, football, basketball, lacrosse, racquet sports, tennis, fencing, golf, and water polo. Screens should be conducted prior to beginning one of these sports to monitor for preexisting eye conditions or a family history that could predispose an athlete to an eye injury[4].

The most common mechanism of eye injury is blunt trauma; however, other types include radiation and penetration. An impact from an object smaller than the eye tends to cause more internal eye trauma, while objects larger than the eye tend to cause more orbital fractures. Penetrating injuries can be caused by fish hooks or broken eyeglasses, while radiation tends to occur while skiing[4].

When examining a patient, a thorough patient interview should be conducted to determine the mechanism of injury. The physical exam should include testing of the visual field, ocular muscles, pupil size and reflexes, and fundoscopic evaluation of the red reflex[4]. The examiner may be able to treat simple abrasions and foreign body removals on site, however, should refer if any of the following signs and symptoms are found upon examination.

- Sudden decrease in or loss of vision

- Loss of field of vision

- Pain on movement of the eye

- Photophobia

- Diplopia

- Proptosis of the eye

- Light flashes or floaters

- Irregularly shaped pupil

- Foreign-body sensation/embedded foreign body

- Red and inflamed eye

- Hyphema (blood in anterior chamber)

- Halos around lights (corneal edema)

- Laceration of the lid margin or near medial canthus

- Subconjunctival haemorrhage

- Broken contact lens or shattered eyeglasses

- Suspected globe perforation[4]

Returning to play after an eye injury requires careful consideration. The athlete needs to be cleared by an eye doctor, have a full visual return, and wear protective glasses[4].

To prevent these injuries from occurring, athletes in high-risk sports should consider donning protective eyewear during play. Eyewear should be tailored to each sport, but always made of high-impact resistant plastic that reduces ultraviolet radiation and can be made with or without a prescription[4].

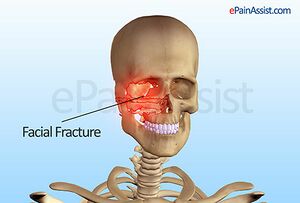

Facial Fractures[edit | edit source]

Common sports for facial fractures to occur include baseball, softball, soccer, and horseback riding, and the most common bones fractured include nasal, orbital and skull bones. A collision, fall, or being struck with a ball is usually the mechanism of injury for facial fractures[5].

The patient interview is important to help gauge the severity of the injury on site, including ruling out a concussion. After a blow to the head, a player should be screened for a concussion with a test such as the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 3 (SCAT), which evaluates signs, symptoms, balance, and memory along with a neurologic and cognitive screening. It also gives recommendations on when an athlete should return to play based on the severity of his or her score[7].

Management of facial fractures depends on the location and severity. On site, if a fracture is suspected, the player should be transported to the nearest hospital. Fractures sites that are especially concerning are the orbit, which could cause damage to the eye, or nasal fractures, which could impair breathing. Return to play will depend on the severity of the injury, as well as other injuries incurred with the fracture. Fracture healing time (typically up to 8 weeks) must be considered, as well as if the player is continuing to have pain or other symptoms[8].

To help prevent facial fractures from occurring, coaches should always adhere to the rules of the game to decrease unnecessary roughness. Protective helmets and eyewear should be worn when appropriate. Coaches also need to keep an eye on novice players because their level of skill and knowledge of the game could lead to injury of themselves or other players. Finally, coaches should ensure players get adequate rest, especially when there are multiple practices or games in a day[5].

Facial Abrasions & Lacerations[edit | edit source]

Sports are a tremendous contributor to facial lacerations and abrasions, causing up to 29% of all reported facial injuries [8]. The primary fear with any athlete who has experienced a facial injury is underlying damage that may have affected consciousness, respiration, or vision. Because of the severity of these types of injuries, evaluations always start with the emergency medical response “ABCDE” approach: Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, and Exposure/Environmental control [8]. After the medical professional rules out a life-threatening injury and/or concussion, then he or she can bandage the wound for the athlete to return to competition.

Facial abrasions are a non-severe, superficial injury involving the epidermal and possibly superficial dermal layers of the skin. Most abrasions occur because of shear forces caused by an athlete sliding over a rough playing surface such as grass or turf [9]. Athletes with facial abrasions can easily return to competition after a medical professional has washed out the wound with soap and water and removed any foreign debris from the area. If there is too much debris or if it is too deep in the wound to be removed safely, then the athlete should be taken to a doctor for removal [8]. However, abrasions can easily become infected, so it is important to use an aseptic dressing to protect the wound. Most abrasions will heal in a few days [9].

Lacerations are the most common sports-related injuries to the face [9]. Sharp objects are not the only cause of lacerations. “Burst lacerations” occur when a blunt trauma of the soft tissue over a bony area will cause a tear in the skin. These injuries usually occur on the forehead, cheek, teeth, or chin [9]. Lacerations bleed easily, so it is important to put pressure on the wound to control it. Once the bleeding is under control, the medical professional should sterilise the cut with saline to prevent infection. Many trainers will choose to close the wound with sutures, but if it is not a significant laceration then some will opt to use a Band-Aid or other type of adhesive bandage until after the game is over and the athlete can be taken to a doctor [8]. Most studies recommend that adhesive should be used for superficial cuts smaller than 4 cm while sutures are used for deeper and larger lacerations. One randomised control trial shows that Dermabond (a brand of tissue adhesive) had a better cosmetic outcome than sutures at 1 year following facial plastic surgery, and it had no increased risk for wound dehiscence or infection [10]. As physical therapists, it is better to use adhesives in competition settings until a doctor can evaluate whether the athlete will need stitches or not.

Eyelid lacerations are also a big concern because of the possibility of foreign bodies or penetrating injuries into the eye itself. Eyelid lacerations can cause vision loss since the cornea will dry out when the eyelid is unable to close properly [8]. Lacerations to the medial part of the eyelid can damage the tear ducts while lacerations to the upper eyelid can damage the levator palpebrae muscle, which can cause the eyelid to permanently drop [8]. Eyelid lacerations during competition are cared for a little differently than other facial lacerations due to the possibility of the eye drying out and causing permanent damage. The primary goal immediately following an injury to the eyelid is to apply an antibiotic ointment or artificial tears to the wound and cover the entire eye with moistened gauze to prevent the cornea from getting too dry; athletes with an eyelid laceration are taken to the doctor immediately for surgical repair [8].

If lacerations are not treated properly, excessive scar tissue can form and alter the cosmetic appearance of the face [9]. This can cause significant psychological and psychosocial effects on the athlete, especially if they are female. Some lacerations may have significant complications if they involve a severed nerve, vessel, or gland [8]. A laceration of the facial nerve will cause a possibly permanent facial droop and asymmetry. The earlier that a facial nerve laceration is diagnosed, the better chance the athlete has for nerve regeneration. Deep cheek lacerations typically involve the parotid duct, so saliva draining from the laceration is a common symptom [8]. In summary, many underlying structures are apt to be injured with a facial laceration. The job of athletic trainers and physical therapists is to clean and dress the wound, and any complicated laceration injuries should be immediately referred to a surgeon [8].

According to Romeo, Hawley, Romeo, Romeo, & Honsik (2007) [11], athletic trainers and/or physical therapists should adhere to the following steps in the sideline management of facial injuries:

- Assess the athlete’s airway, breathing, and circulation following typical emergency response guidelines

- Evaluate for an intracranial or cervical spine injury

- Inspect all parts of the face for bleeding, swelling, bruising, and asymmetry

- Palpate the bony aspects of the face (forehead, cheekbones, jaw, etc.) for pain, instability, and/or subluxation

- Assess cranial nerve function

Romeo et al. [11] also provide a list of criteria for the athlete to be able to return to competition following a facial laceration:

- Trainer/Therapist has ruled out any underlying injury including eye injuries, fractures, nerve lacerations, and cervical spine injuries

- Bleeding stopped and hemostasis achieved

- Vision is normal

- Athlete has decided to return to competition after being informed of the risks

- The rules allow the athlete to return to play with an open wound OR if the rules do not allow an open wound then it is closed and bandaged temporarily

Medical professionals should follow these rules to ensure that athletes will not worsen the injury if they decide to return to play. It is important to know the rules about returning to competition with an open wound for each specific sport that the trainer or therapist is covering.

.

Lip, Tongue, and Tooth Injuries[edit | edit source]

Lip, tongue and tooth injuries are commonplace in sports and are not limited to contact sports. Participation in sports is one of the top causes of dental trauma, accounting for 13 – 39% of all dental trauma [12]. Lip and intraoral injuries, including injuries of the tongue, have been reported to make up almost 25% of all sports-related maxillofacial injuries [13]. The incidence rate of at least one orofacial injury per season among high school athletes, including dental trauma and lacerations of the tongue or lips, has been reported as 25% in soccer, 50% in basketball, and 75% in wrestling. Of the athletes included in the study, only 6% reported using mouth guards and none sustained injuries [14].

As a sports medicine provider, one should be able to recommend and fit sports equipment properly to reduce the likelihood of injury, including mouth guards. The effectiveness of mouthguards has been well established in sports medicine literature, including a 2007meta-analysiss. The authors concluded mouth guards provide many benefits including: reduce mandibular deformation, increase the force required to fracture teeth, reduce the number of fractured teeth at a given force, and dampen impact forces. Overall, the risk of orofacial injury was 1.6 – 1.9 times higher in those who did use a mouth guard during sport [15].

Following an injury to the lip, tongue, or teeth, the athlete’s overall status should be evaluated by the sports medicine provider, including vital signs, airway integrity, and neurologic signs as indicated. All orofacial injuries should be assessed immediately, as many are considered urgent and may cause significant morbidity and mortality if not addressed within a few hours. Fractures and avulsions of the teeth or alveolar ridges and significant lacerations of lips or tongue are all considered urgent and the athlete should seek treatment promptly [16].

Lacerations of the lip or tongue should be covered with gauze and given pressure, and when blood flow slows down the wound should be examined, cleaned, and determined if sutures are required for closure [17]. A tongue may not require surgical closure if the laceration is superficial and does not gape widely when the tongue is extended [18]. Simple lacerations may be closed with sterile dressings, tissue glues, or steri-strips [19]. On the other hand, tongue lacerations with continued excessive bleeding should be referred for surgical intervention [18]. Following any significant intraoral laceration, the use of penicillin prophylactically is supported by current evidence [19].

Prior to evaluating a tooth injury, the initial sports medicine provider must consider evaluating the athlete for a concussion and head or neck injury [8]. Dental trauma typically occurs as a result of a direct force to the teeth or from a force to the mandible causing a tooth to tooth contact [17]. If the affected tooth is air sensitive, this is considered an urgent situation requiring dental treatment as soon as possible [8]. The goals of treatment for any trauma to a tooth are the same [17], with the first goal being of primary concern for initial sports medicine providers:

• Retain tooth in dental arch

• Maintain vitality of dental pulp

• Prevent internal and external root resorption

• Restore injured tooth to form, function, and esthetics

The severity of crown fractures can be described based on the layers affected, which can be the enamel, dentin, and pulp. Fractures involving only the enamel are not an emergency and often go unnoticed by the athlete. The athlete may report a chipped tooth that feels rough on the tongue [17]. Fractures that extend into the dentin will be painful with air exposure, cold drinks, or to the touch. If possible, the tooth fragment should be located and placed in milk or a balanced saline solution, and the athlete should seek treatment from a dentist as soon as possible for the best prognosis [17]. Fractures extending into the pulp are the most severe type of crown fracture. The proper treatment can be difficult to determine and is outside the scope of this article. However, if the tooth is producing pain and blood is seeping from the pulp chamber, this is a dental emergency and dental care should be sought immediately [17].

Fractures occurring within the root are categorised based on thirds. Fractures occurring in the apical third have the best prognosis of all root fractures and often go unnoticed [17]. Fractures occurring in the middle third have a good prognosis for proper healing, but treatment should be sought as soon as possible. Upon examination the affected tooth will appear longer and partially raised from the alveolar socket and bleeding at the gums may be present. Immediate care should include carefully repositioning the tooth manually followed by having the athlete bite down on gauze to place pressure on the tooth to keep it in place. Following stabilisation, the athlete should seek dental care immediately to determine the necessary treatment [17]. Fractures occurring in the cervical third, in the region where the root and crown meet, have the worst prognosis for maintaining tooth vitality. The initial management is the same as described for middle third fractures [17].

With a complete tooth avulsion, it is essential to begin treatment as quickly as possible following the avulsion. If the tooth can be located, it should only be handled by the crown and cleansed with either saline or milk. The tooth can then be placed back into the alveolar socket and the athlete should bite down to stabilise the tooth and seek dental treatment immediately. Re-implantation of the tooth within 30 minutes results in a greater than 90% chance of saving the tooth. While a delay of more than 2 hours results in a 5% chance of survival [8].

Temporomandibular Joint Injuries[edit | edit source]

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) injuries are not very common injuries in athletics. The most common sporting events that involve TMJ injuries are those that are classified as contact or collision sports. The most common sports include football, rugby, soccer, wrestling, karate, boxing, and mixed martial arts [20]. TMJ injuries are a sub-category of temporomandibular dysfunctions (TMD). TMD includes:

• Preauricular pain

• Temporomandibular joint dysfunction

• Pain in the muscles of mastication

• Limitations or deviations in mandibular range of motion

• Crepitus during mastication or mandibular function

• Combination of the above [20]

There are multiple causes of TMD or TMJ injuries. The most common are direct trauma to the mandible. Trauma to the mandible and face itself is protected by wearing proper headgear, such as the case in football, wrestling, hockey, and baseball. However, this headgear is often inadequate in the protection of the mandible [20]. Sports that do not require headgear, but have collisions or contact, including soccer, rugby, and boxing. Direct blows to the mandible may lead to dislocations, acute capsulitis, TMJ disc displacement, ligamentous laxity, or TMJ derangements [20].

TMJ dislocations involve a non-self-limiting displacement of the condyle outside of its functional position within the glenoid fossa and posterior slope of the articular eminence [21]. The most common TMJ dislocation is anterior to the auricular eminence, however, there have been reports of dislocations medially, laterally, posteriorly, and intracranially [21]. Acute dislocations are normally isolated events, and when proper care is taken, usually have no long-term implications.

Acute capsulitis is characterised by an acute inflammatory response resulting from direct trauma to the mandible. This inflammatory response leads to irritation of the synovial tissues lining the joint and increased volume of synovial fluid within the joint space, resulting in pain [22]. This injury leads to the immediate development of swelling in and around the joint, painful function of the mandible, and occlusal changes.

Direct trauma may cause disc displacement of the TMJ. This disc displacement may result in significant reduction in Range Of Motion of the mandible and may be painful in some cases. The joint may be locked in closed or open tendencies, with a limited range of motion in the opposite directions [22]. When this type of injury happens, athletes may become extremely anxious at their inability to control the motions of their mouth, and it is very important to control the situation and athletes’ emotions in a calm, timely manner.

TMJ injuries may also arise from stress. Trauma is often the primary cause of injury, but the symptoms of the injury are exacerbated by stress of the athlete. Athletes face varying levels of stress in their playing careers, such as competing for playing time, concern over performances, maintaining eligibility, and the stress of everyday life [20].

Another cause of TMJ injuries in sport is structural anomalies. Structural anomalies include malocclusion, enlarged mandibular condyles, decreased joint space, or missing teeth (sailors). These structural anomalies predispose athletes to TMJ injuries by altering mandibular function and mechanics.

Evaluation of suspected TMJ injuries should include a thorough history, postural inspection, palpation, Range Of Motion testing, muscle testing, and referral for special testing. While collecting a thorough history, the athlete should be questioned over recent and past dental history since dental procedures may lead to development of TMD. Common signs and symptoms of TMD include jaw ache, earache, headache with possible dizziness, facial pain, decreased Range Of Motion, and crepitus with movements of the mandible [20]. The sports medicine practitioner should be conscious of what falls within his or her scope of practice with issues of the TMJ and know when a referral is appropriate.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Öztürk S, Kılıç D. What is the economic burden of sports injuries?. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 2013;24(2):108-111. doi:10.5606/ehc.2013.24

- ↑ Ohana O, Alabiad C. Ocular related sports injuries. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2021 Jun 1;32(4):1606-11.

- ↑ Ramagoni NK, Singamaneni VK, Rao SR, Karthikeyan J. Sports dentistry: A review. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 2014 Dec;4(Suppl 3):S139.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Rodriguez JO, Lavina, AM. Prevention and treatment of common eye injuries in sports. Am Fam Physician 2003;67:1481-8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 MacIsaac ZM, Berhane H, Cray, Jr. J,fckLRNoel S. Zuckerbrau NS, Losee JE, Grunwaldt LJ. Nonfatal sport-related craniofacial fractures:fckLRCharacteristics, mechanisms, and demographicfckLRdata in the pediatric population. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;131:1339-47.

- ↑ Pramod Kerkar, M.D., FFARCSI, DA Pain Assist Inc. Available from: www.epainassist.com/sports-injuries/head-and-face-injuries/facial-fractures(accessed 26 Dec 2022).

- ↑ SCAT3. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:259.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 Reehal P. Facial injury in sport. Curr Sports Med Rep 2010;9:27-34.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Schenck, R. C. Athletic training and sports medicine. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 1999.

- ↑ Toriumi DM, O'Grady K, Desai D, Bagal A. Use of octyl-2-cyanoacrylate for skin closure in facial plastic surgery. Plast Recon Surgery 1998;102:2209-2219.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Romeo SJ, Hawley CJ, Romeo MW, Romeo JP, Honsik KA. Sideline management of facial injuries. CSMR 2007;6:155-161.

- ↑ Tuli T, Hächl O, Hohlrieder M, Grubwieser G, Gassner R. Dentofacial trauma in sports accidents. Gen Dent 2002;50(suppl 3):274-9.

- ↑ Hill C, Burford K, Martin A, Thomas D. A one-year review of maxillofacial sports injuries treated at an accident and emergency department. Brit J Oral Mas Surg 1998;36(suppl 1):44-7.

- ↑ Kvittem B, Hardie N, Roettger M, Conry J. Incidence of orofacial injuries in high school sports. J Public Health Dent 1998;58(suppl 4):288-293.

- ↑ Knapik J, Marshall S, Lee R, Darakjy S, Jones S, Jones B, et al. Mouthguards in sport activities: history, physical properties and injury prevention effectiveness. Sports Med 2007;37(suppl 2):117-144.

- ↑ Howes D, Dowling P. Triage and initial evaluation of the oral facial emergency. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2000;18(suppl 3):371-8.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 Ranalli D. Dental injuries in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2005;4(suppl 1):12-17.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Armstrong B. Lacerations of the mouth. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2000;18(suppl 3):471.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Echlin P, McKeag D. Maxillofacial injuries in sport. Curr Sports Med Rep 2004;3(suppl 1):25-32.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Sailors, M. Evaluation of sports-related temporomandibular dysfunctions. J of AT 1996;31(4):346-350.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Liddell, A, Perez, D. Temporomandibular joint dislocations. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N AM 2015;27:125-136.