Filariasis

Original Editors - Kim McMillin from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page. Read more.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lymphatic filariasis is a disease associated with parasitic infection of one of three different nematodes: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, or Brugia timori. The microscopic worms enter the human body via mosquito transmission- in both children and adults- and can live up to 5-7 years in the lymphatic system. Although most people who are infected are asymptomatic, a small percentage of people will develop extreme lymphedema and multiple secondary infections as a result of years of exposure to the parasites. (CDC)

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

It is estimated that more than 120 million people in 80 countries worldwide are currently infected with one of the three nematodes. Greater than 90% of those 120 million people are infected with the Wuchereria bancrofti filaria, and the majority of the remaining ~10% are infected with the Brugia malayi filaria. Reports also suggest that more than 40 million people are significantly dibilatated and disfigured by the disease. (Lymphatic filariasis: the disease and its control. Fifth report of the WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1992; 821:1.)

Lymphatic filariasis is endemic is the tropic and sub-tropics of Southeast Asia, Africa, the India Subcontinent, the Pacific islands, and parts of the Caribbean and Latin America. (CDC; Ngwira BM, Jabu CH, Kanyongoloka H, et al. Lymphatic filariasis in the Karonga district of northern Malawi: a prevalence survey. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2002; 96: 137.)

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The majority of people who become infected with filariasis do not show any overt clinical signs or symptoms, although they will experience irregularities in their lymphatic drainage. It is estimated that only one-third of those infected by any of the filarial nematodes show obvious clinical features of the condition. Experts have attributed the severity of symptoms as being positively correlated with extended time of exposure and accumulation of worms. (CDC)

ACUTE Signs & Symptoms:

- Adenolymphangitis

- Filarial fever

- Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia

Acute adenolymphangitis: Characteristics include painful lymphadenopathy and retrograde lymphangitis that most often affect the inguinal nodes, genitalia, and lower extremities leading to extreme edema, elephantiasis, and sometimes skin breakdown and secondary infections. Flare-ups can last 4-7 days and occur up to 4 times per year depending on the severity of the lymphedema. (Pani SP, Srividya A. Clinical manifestations of bancroftian filariasis with special reference to lymphoedema grading. Indian J Med Res 1995; 102:114)

Filarial fever: Often an acute fever that occurs independently of any other signs of lymphadenopathy. Filarial fever is sometimes misdiagnosed as a manifestation of malaria and other tropical diseases because of the lack of associated symptoms.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia: Most commonly seen in young males and is caused by microfilariae being trapped in the lungs. The immune system exhibits a respiratory "hyperresponsiveness" to the problem, causing excessive nocturnal wheezing.

CHRONIC Signs & Symptoms:

- Lymphedema

- Renal Pathology

- Secondary infections

Lymphedema: Commonly involves vessels in the inguinal and axillary lymph nodes, affecting all four extremities. Early stage lymphedema is usually characterized by pitting edema, but more chronic stages exhibit non-pitting edema with hardening of the surrounding tissues, eventually leading to hyperpigmentation and hyperkeratosis. Chronic manifestations can also involve the breasts and male genitalia. Hydroceles (swelling of the scrotum) can be greater than 30cm in diameter, but are usually painless unless bacterial infection is present.

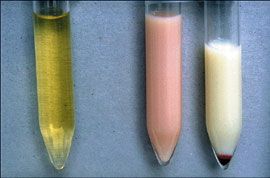

Renal Pathology: When renal system lymphatic are obstructed, lymph fluid can be passed into the renal pelvis. Chyluria, or lymph fluid in the urine, causes a milky appearance in the excreted urine. Hematuria and proteinuria may also be present and can eventually cause nutritional deficiencies and anemia.

Secondary infections: Bacterial and fungal infections become problematic in lymphatic filariasis due to edema-causing skin folds and skin tears.

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

add text here

Medications[edit | edit source]

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) (Tisch DJ, Michael E, Kazura JW. Mass chemotherapy options to control lymphatic filariasis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:514)

- Drug of choice for lymphatic filariasis caused by any of the three nematodes

- Potent microfilaricidal agent, but the mode of action is uncertain

- Also kills approximately 50% of adult worms

- Not distributed for use in the US, but can but can be obtained through the CDC under an Investigational New Drug protocol

- Has been added to salt in some endemic regions

- Side effects include fever, headache, anorexia, nausea, and arthralgias.

- Not safe for use during pregnancy

Ivermectin (Cao WC, Van der Ploeg CP, Plaiser AP, et al. Ivermectin for the chemotherapy of bancroftian filariasis: a meta-analysis of the effect of single treatment. Trop Med Int Health

- Single dose can reduce microfilaremia by 90% in W.bancrofti filariasis

- No significant effect on adult worm viability, so results are not sustained without repeated doses

- May be beneficial in affecting worm fertility

Albendazole

- No direct effect on microfilariae; slow decline over a 6-8 week period

- 14-day courses of treatment show a significant decrease in macrofilariae

Doxycycline (Taylor MJ, Makunde WH, McGarry HF, et al. Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline treatment of Wuchereria bancrofti: a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 365:2116)

- Simultaneously prevents adult worms from reproducing and produces macrofilaricidal effects up to 80-90%

- Clinical improvement in edema

- Fewest adverse reactions

Recommended treatment?

There is no one best treatment for filariasis. Efficacy is greatest when a combination of drugs are used; most commonly, DEC in addition to Ivermectin or Albendazole. Unfortunately, certain endemic regions are also susceptible to infection by other nematodes: onchocerciasis (also known as river blindness) and loiasis (also known as African eye worm). Use of either DEC or Ivermectin in those who are co-infected can cause serious adverse effects, including but not limited to encephalopathy. (http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/treatment.html)

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Nonspecific test abnormalities:

- Eosinophilia (>3000/microliter) (Ottesen EA, Weller PF. Eosinophilia following treatment of patients with schistosomiasis mansoni and Bancroft's filariasis. J Infect Dis 1979; 139:343)

- Microscopic hematuria

- Microscopic proteinuria

Blood smears:

- Samples are drawn ideally between 10pm and 2am due to peak biting time of mosquito vectors

- 20 microliters of blood can detect microfilariae, but a 1 mL blood sample may be required to make a diagnosis

- >10,000 microfilariae per 1 mL of blood can be found in endemic regions

- Samples are stained and centrifuged

- Microfilariae species can be differentiated by morphological characteristics

Antibody tests:

- Serologic testing for filarial antibodies can detect elevated levels of IgG and IgE

- Poor specificity

- Cannot distinguish between filarial types

- Cannot differentiate between past and present infections

- Newer tests are being developed that look at specific anti-filarial IgG4 antibodies for showing active infections (Lai RB, Ottesen EA. Enhanced diagnostic specificity in human filariasis by IgG4 antibody assessment. J Infect Dis 1988; 158:1034)

Antigen tests:

- Detect the presence of adult worms

- Circulating Filarial Antigen (CFA) tests are considered the gold standard for diagnosing Wuchereria bancrofti infections

- No antigen testing currently available for Brugian malayi filariasis (Weil GJ, Ramzy RM. Diagnostic tools for filariasis elimination programs. Trends Parasitol 2007; 23:78)

Radiology:

- Ultrasound can be used to detect adult worms and vessel destruction

- Ultrasound can localize worms in epididymal and breast lymphatics

- "Filarial dance", or the constant movement of live worms, can be picked up with ultrasound imaging and is sometimes used to monitor effectiveness of certain treatments (Mand S, Debrah A, Batsa L, et al. Reliable and frequent detection of adult Wuchereria bancrofti in Ghanaian women by ultrasonography. Trop Med Int Health 2004; 9:1111)

- Lymphoscintigraphy is used for assessment of the extent of lymphatic destruction (Freedman DO, de Almeida Filho PJ, Besh S, et al. Lymphoscintigraphic analysis of lymphatic abnormalities in symptomatic and asymptomatic human filariasis. J Infect Dis 1994; 170:927)

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

add text here

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

add text here

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

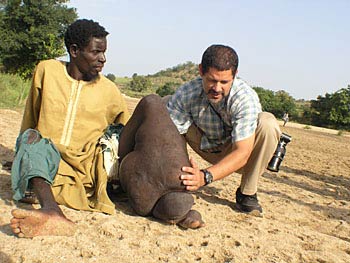

Clinical manifestations of filariasis such as lymphedema and elephantiasis are caused by prolonged exposure to filariae and the mosquitos that transmit them in endemic regions. These affected individuals are usually not actively infected; rather, they are suffering from the effects of years of exposure to one of the three nematodes. Medical management is not appropriate for these individuals.

Physical therapy management of the disease primarily consists of treatment from a lymphedema therapist, along with education of proper skin care and hygiene. Appropriate exercise prescription and wound care management are also indicated. There is no physical therapy intervention indicated for hydrocele; those infected usually do not respond well to DEC, and surgery is required in some cases. (CDC)

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnoses[edit | edit source]

Most highly suspected causes of Lymphadenopathy:

- Mononucleosis

- Epstein-Barr Virus

- Toxoplasmosis

- Cytomegalovirus

- HIV

- Cat-scratch disease

- Pharyngitis

- Tuberculosis

- Secondary syphilis

- Hepatitis B

- Lymphogranuloma venereum

- Chancroid

- SLE

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Lymphoma

- Leukemia

- Serum sickness

- Sarcoidosis

- Kawasaki disease

Travel-related causes of Lymphadenopathy:

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Bubonic Plague

- Histoplasmosis

- Scrub typhus

- African trypanosomiasis

- American trypanosomiasis

- Kala-azar

- Typhoid fever (http://www.aafp.org/afp/981015ap/ferrer.html)

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Barreto SG, Rodrigues J, & Pinto RGW. Filarial granuloma of the testicular tunic mimicking a testicular neoplasm: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2008; 2(321).

Available at: http://jmedicalcasereports.com/content/2/1/321

Cengiz N, Savaş L, Uslu Y, Anarat A. Filariasis in a child from southern Turkey: a case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2006 Apr-Jun;48(2):152-4.

Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16848117

Kapoor AK, Puri SK, Arora A, Upreti L, Puri AS. Case report: Filariasis presenting as an intra-abdominal cyst. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2011;21:18-20.

Available at: http://www.ijri.org/text.asp?2011/21/1/18/76048

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Global Alliance to Eliminate LF: http://www.filariasis.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/epi.html

Tropical Disease Research: http://www.TropIKA.net

World Health Organization: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs102/en/

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1LuCQHj6kRF7j_ljRKzw4jWi_VSnRV5z-VpbnDe_osv1Q_UIgA|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.