Functional Anorectal Pain: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (references changed) |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User: | <div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User: Adu Omotoyosi Johnson|Adu Omotoyosi Johnson]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

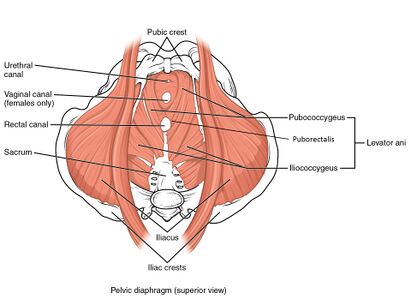

[[File:Muscles of the Pelvic Floor.jpg|thumb|411x411px|Muscles of the Pelvic Floor]] | |||

Functional anorectal disorders are characterized by constipation and are often associated with ineffective defecation, inappropriate contraction or weakening of [[Pelvic Floor Anatomy|pelvic floor muscles]], abnormal propulsive forces, or outlet obstruction. Initial treatment is largely nonsurgical and often involves behavioral and diet modification, fiber, and bulking agents. [[Biofeedback]] can also be effective for some of these disorders. Surgical management is controversial and with limited studies of varying success. | |||

Functional anorectal include [[Proctalgia Fugax|proctalgia fugax]], [[Levator Ani Muscle|levator ani]] syndrome, and unspecified functional anorectal pain<ref name=":6">Drossman DA, Chang L, Chey WD, Kellow J, Tack J, Whitehead WE and the Rome IV Committees, editors. Rome IV—functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. 4th Edition. Vol 2. Rome Foundation Inc, 2016. p531-535 </ref>. These three types of anorectal disorders are chiefly differentiated by the length of time pain is present and by the feature or lack of anorectal tenderness<ref name=":5">Rao SS, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, Felt-Bersma R, Knowles C, Malcolm A, Wald A. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5035713/pdf/nihms776224.pdf Anorectal disorders.] Gastroenterology. 2016 May 1;150(6):1430-42.</ref>. However, these pain disorders do coincide and are similar to each other<ref name=":5" /><ref name=":7">Bharucha AE, Lee TH. [https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/action/showPdf?pii=S0025-6196%2816%2930503-1 Anorectal and pelvic pain.] InMayo Clinic Proceedings 2016 Oct 1 (Vol. 91, No. 10, pp. 1471-1486). Elsevier.</ref>. | |||

== Functional Anorectal Disorder Type Definitions == | == Functional Anorectal Disorder Type Definitions == | ||

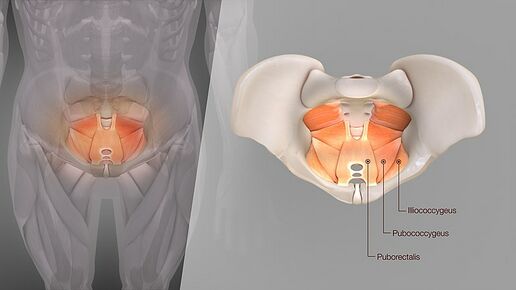

[[File:Medical Animation Levator Ani structure.jpg|thumb|516x516px|Levator Ani structure|alt=]]Three Types Identified: | |||

#[[Levator Ani Muscle|Levator Ani]] Syndrome: other names include levator spasm, puborectalis syndrome, and pelvic tension myalgia<ref name=":6" />. In this syndrome, pain can be present for 30 minutes to being ceaseless. Its distinguishing attribute is on physical examination a hypertonic levator ani muscle and soreness on palpation of the pelvic floor or [[Female Genital Tract|vagina]]<ref name=":6" />. | |||

# Unspecified Functional Anorectal Pain: In this syndrome, the pain will also be present for 30 minutes to be continuous in the rectum. However, it does not present with levator ani soreness on palpation<ref name=":6" />. | |||

#[[Proctalgia Fugax]]: For this disorder, pain is momentary, present for seconds to minutes, and happens sporadically such as once a month or less<ref name=":5" />. | |||

In this syndrome pain will also be present for 30 minutes to | |||

For this disorder pain is momentary, present for seconds to minutes and happens sporadically such as once a month or less<ref name=":5" /> | |||

== Epidemiology == | == Epidemiology == | ||

To date there is no currently published data on the commonness to which chronic anorectal pain is came upon in clinical practice<ref name=":6" />. | |||

== Pathophysiological Process == | == Pathophysiological Process == | ||

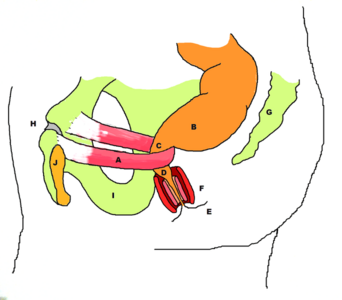

There is poor insight into the pathophysiology of functional anorectal pain | [[File:Stylized depiction of action of puborectalis sling.png|alt=|thumb|342x342px|A: Puborectal Sling ]]There is a poor insight into the pathophysiology of functional anorectal pain which sometimes occurs without any pathology<ref>Iqbal F, Beggs AD, Holt T, Bowley DM. [https://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f4192 A pain in the bottom]. Bmj. 2013 Jul 1;347:f4192.</ref>. Levator ani syndrome is thought to be caused by hypertonic pelvic floor muscles<ref name=":6" /> and may be identified by an increase in muscle tone of the puborectalis sling<ref>Gilliland R, Heymen JS, Altomare DF, Vickers D, Wexner SD. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02054987 Biofeedback for intractable rectal pain]. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1997 Feb 1;40(2):190-6.</ref>. It was found the presence of pelvic floor muscle spasms, raised anal resting pressure<ref>Grimaud JC, Bouvier M, Naudy B, Guien C, Salducci J. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02050352 Manometric and radiologic investigations and biofeedback treatment of chronic idiopathic anal pain]. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1991 Aug 1;34(8):690-5.</ref> and dyssynergic defecation<ref name=":11">Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, Romito A, Whitehead WE. [https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(09)02237-9/fulltext Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome.] Gastroenterology. 2010 Apr 1;138(4):1321-9.</ref> are contributors to levator ani syndrome. The latter refers to inefficiency through the defecation process in the anorectum<ref name=":7" /> but does not include [[constipation]]<ref name=":6" />. | ||

== Clinical Presentation == | |||

[[ | Patients presenting with levator ani syndrome or unspecified functional anorectal pain often describe the feeling of pain as a dull ache or a sense of pressure utmost in the rectum. This is usually aggravated by a long duration of sitting, such as a long-distance car journey, and lessened by standing or lying <ref name=":7" /><ref name=":0">Drossman DA. [https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(06)00503-8/fulltext The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process.] gastroenterology. 2006 Apr 1;130(5):1377-90.</ref><ref>Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE and the Rome II Multinational working teams, editors. Rome II: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2nd Edition. Degnon Associates Inc, 2000. p483-542</ref>. The pain rarely occurs at night but its severity can rise throughout the day. It may be made more severe with sexual intercourse, stress, or defecation<ref name=":2" /> <ref name=":3">Gilliland R, Heymen JS, Altomare DF, Vickers D, Wexner SD. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02054987 Biofeedback for intractable rectal pain.] Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1997 Feb 1;40(2):190-6.</ref>. Associations have been made between patients presenting with levator ani syndrome, who are also experiencing psychosocial distress<ref name=":7" /> and impacted [[Quality of Life|quality of life]]<ref>Heymen S, Wexner SD, Gulledge AD. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8500378/ MMPI assessment of patients with functional bowel disorders]. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1993 Jun 1;36(6):593-6.</ref>, this includes [[Generalized Anxiety Disorder|anxiety disorders,]] [[depression]] , and [[Stress and Health|stress]]<ref name=":2">Wald A. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S088985530570176X Functional anorectal and pelvic pain.] Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2001 Mar 1;30(1):243-52.</ref><ref>Renzi C, Pescatori M. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02237201 Psychologic aspects in proctalgia.] Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2000 Apr 1;43(4):535-9.</ref>. Other causative factors to functional anorectal pain can include childbirth<ref>Salvati EP. [https://europepmc.org/article/med/3298056 The levator syndrome and its variant.] Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 1987 Mar 1;16(1):71-8.</ref> and surgery, inclusive of [[Disc Herniation|herniated lumbar disc]], [[hysterectomy]], or low anterior resection<ref name=":7" />. | ||

]] | |||

A digital rectal examination may be performed to ascertain the presence of tenderness when traction is applied to the [[Levator Ani Muscle|levator ani muscle]]<ref name=":8">Whitehead WE, Wald A, Diamant NE, Enck P, Pemberton JH, Rao SS. [https://gut.bmj.com/content/45/suppl_2/II55?utm_source=trendmd&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=gut&utm_content=consumer&utm_term=0-A Functional disorders of the anus and rectum]. Gut. 1999 Sep 1;45(suppl 2):II55-9.</ref>. Often a lack of symmetry may be noted on the physical exam and pain is mainly left-sided. Presently, there is no logic as to why this side is generally more affected<ref name=":8" /> | |||

'''Summary of clinical features for one of the subtypes of functional anorectal pain'''<ref name=":7" />'''.''' | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ | |+ | ||

!Variable | !Variable | ||

!Levator ani syndrome | !Levator ani syndrome | ||

| Line 44: | Line 34: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Sex | |Sex | ||

| | |More in females than male | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Pain Quality | |Pain Quality | ||

| Line 79: | Line 69: | ||

No | No | ||

|} | |} | ||

== Diagnostic Criteria == | == Diagnostic Criteria == | ||

Diagnosis of Levator Ani Syndrome, as per Rome IV criteria | Diagnosis of Levator Ani Syndrome, as per Rome IV criteria <ref name=":6" />, must present with all symptoms listed below: | ||

* Chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching. | * Chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching. | ||

* Episodes last 30 minutes or longer. | * Episodes last 30 minutes or longer. | ||

* Soreness during traction on the puborectalis. | * Soreness during traction on the puborectalis. | ||

* Elimination of other sources of rectal pain, see differential diagnosis below. | * Elimination of other sources of rectal pain, see differential diagnosis below. | ||

* Criteria | * Criteria are to be met for the last 3 months with symptom onset at a minimum of 6 months before diagnosis. | ||

The diagnosis of unspecified functional anorectal pain has the same criteria as that for chronic levator ani syndrome, but there is no soreness during posterior traction on the puborectalis muscle. Again criteria | The diagnosis of unspecified functional anorectal pain has the same criteria as that for chronic levator ani syndrome, but there is no soreness during posterior traction on the puborectalis muscle. Again criteria are met for the last 3 months with symptom onset at a minimum of 6 months before diagnosis<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":5" />. | ||

== Management/Interventions == | |||

[[File:Sitz or hip bath.jpeg|thumb|Sitz or hip bath]] | |||

The first line of treatment most commonly provided is reassurance that pain is benign. Conservative lines of treatment are used first in the management of functional anorectal pain, this may include lifestyle adaptations, diet changes, fibers, laxatives, and pelvic floor physiotherapy. However, if conservative management is unsuccessful, these functional disorders can be difficult to treat<ref name=":10">Ooijevaar RE, Felt-Bersma RJ, Han-Geurts IJ, van Reijn D, Vollebregt PF, Molenaar CB. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10151-019-01945-8 Botox treatment in patients with chronic functional anorectal pain: experiences of a tertiary referral proctology clinic.] Techniques in Coloproctology. 2019 Mar 1;23(3):239-44.</ref>. In the instance of levator ani syndrome a range of treatments aimed at relaxing the levator ani muscles may be implemented<ref name=":8" />; | |||

* Digital massage of the levator ani muscles<ref name=":4">Salvati EP. [https://europepmc.org/article/med/3298056 The levator syndrome and its variant.] Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 1987 Mar 1;16(1):71-8.</ref> | |||

* Sitz (or hip) bath<ref name=":9">Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016508506005166 Functional anorectal disorders.] Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr 1;130(5):1510-8.</ref> Person sits in water up to the hips, used to relieve discomfort/ pain in the lower part of the body, works by keeping the affected area clean and increasing the flow of blood to it. | |||

* [[Muscle Relaxant|Muscle relaxant]]<nowiki/>s eg methocarbamol, diazepam<ref name=":9" />, and cyclobenzeprine | |||

* Electrogalvanic stimulation (EGS) | |||

*Sacral nerve stimulation<ref>Dudding TC, Thomas GP, Hollingshead JR, George AT, Stern J, Vaizey CJ. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/codi.12277 Sacral nerve stimulation: an effective treatment for chronic functional anal pain?.] Colorectal Disease. 2013 Sep;15(9):1140-4.</ref> | |||

*[[Biofeedback|Biofeedback training]] A randomized controlled study unveiled that biofeedback is markedly more effective than EGS or digital massage<ref name=":11" />.<ref>Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, Romito A, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010 Apr 1;138(4):1321-9.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2847007/<nowiki/>(accessed 17.5.2022)</ref> In a more recent review, it was reported biofeedback improves the defecation manner and attested effective for above 90% of patients in the short term<ref>Carrington EV, Popa SL, Chiarioni G. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11894-020-00768-0 Proctalgia Syndromes: Update in Diagnosis and Management.] Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2020 Jun 9;22(7):35-</ref>. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|37a_CXKEj5M}}<ref>Mayo Clinic. Pelvic Floor Training. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=37a_CXKEj5M [last accessed 25/09/2020]</ref> | |||

Where conservative management has been unsuccessful botox may be considered as an alternative. In a study conservative management was given for 3 months then treatment with Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A), as well as ongoing physiotherapy by a pelvic floor physiotherapist. BTX-A was found to give a prolonged remedy in 47% of patients with chronic functional anorectal pain. A further 20% had an initial response to treatment but reverted within 3 months<ref name=":10" />. The patient sample size in this study was small, with 113 total. It was noted in patients with solitary hypertonia of the levator ani appeared to present worse than those with only hypertonia of the anal sphincter or a mixture of both, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.06)<ref name=":10" />. In comparison, another earlier study found injection of botulinum toxin into the anal sphincter did not relieve anorectal pain present in levator ani syndrome<ref>Rao SS, Paulson J, Mata M, Zimmerman B. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19222415/ Clinical trial: effects of botulinum toxin on levator ani syndrome–a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study]. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2009 May;29(9):985-91.</ref>. This earlier study did not include the combined management of pelvic floor physiotherapy and botox for these patients<ref name=":10" />, thus highlighting the value of physiotherapy pelvic health intervention for this patient group. | |||

==== Physiotherapy Intervention ==== | |||

To grasp a full insight into the magnitude and attributes of each patient's symptoms and to devise an individualized treatment plan, the physiotherapy appraisal must take into account the patient's diagnosis, the results of any further investigations, conduct a detailed interview, and comprehensive physical examination. The pelvic floor examination in patients with anorectal disorders is the same as that for patients presenting for urinary incontinence, with particular attention on details admissible to the anorectum. | |||

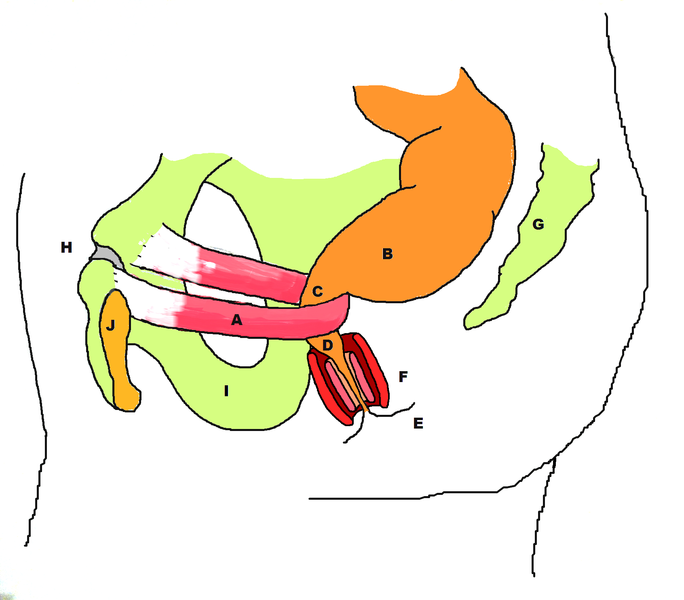

Anal palpation will assess the measure of the anal sphincter and its resting tone and contractility. The anorectal angle can also be surmised; it is normally between 60''h'' and 130''h''. Furthermore, feces in the rectum and its texture can be evaluated here, the tone and contractility of the posterior aspects of the pelvic floor muscles (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and ischiococcygeus). The coccyx is an important bone of attachment for the pelvic floor muscles and it's akin fascia, the location and mobility of the coccyx are also assessed, and painful areas can be palpated. | |||

[[File:Stylized depiction of action of puborectalis sling.png|alt=|center|thumb|684x684px|A-puborectalis, B-rectum, C-level of the anorectal ring and anorectal angle, D-anal canal, E-anal verge, F-representation of internal and external anal sphincters, G-coccyx & sacrum, H-pubic symphysis, I-Ischium, J-pubic bone.]] | |||

A functional assessment is conducted in supine and sitting positions to allow reproduction of the patient's evacuation endeavors, without actual evacuation. This will give information on whether the patient is producing sufficient push, with enough pelvic floor and anal sphincter easing. Spasms in this area may be provoked during this examination. The sitting posture used by the patient during evacuation is recognized. During this examination the way in which intra-abdominal pressure is raised and its impact on the abdominal wall was noted. | |||

Examination of the abdominal wall is conducted through palpation and functional testing. Palpation of the colon and identification of locations of soreness. Functional activities include coughing or lifting of the upper or lower limbs. Breathing pattern and how the diaphragm moves is assessed. Overall a comprehensive examination of the thoracolumbar spine and pelvis can be performed to give insight of the functional abdominopelvic workings<ref name=":1">Neumann P, Gill V. [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s001920200027 Pelvic floor and abdominal muscle interaction: EMG activity and intra-abdominal pressure]. International Urogynecology Journal. 2002 Apr 1;13(2):125-32.</ref>. | |||

= | A variety of physiotherapy treatment choices are accessible, including: | ||

* Patient Education | |||

* [[Therapeutic Exercise|Exercise]] | |||

* Manual techniques | |||

* Biofeedback<ref name=":1" /> | |||

* Electrical stimulation | |||

* Balloon techniques | |||

* Functional applications during the evacuation procedure | |||

The treatment of anorectal disorders is many-sided and the selection of treatment has to account for; | |||

* Contractility and patient mastery of the pelvic floor and the anus | |||

* Receptiveness and Conformity at the Rectum | |||

* Intestinal motion | |||

* Evacuation procedure | |||

* Diet | |||

* [[Psychological Basis of Pain|Yellow flags]] | |||

To give some further detail into the physiotherapy treatments one can begin to give suitable information at the subjective interview, such as bowel and bladder routines, and diet to establish stool consistency and general health. Thereafter, using a pelvic model, drawings, an information pamphlet, and an evacuation diary to give insight into bowel routines, the patient will prevail of a basic understanding of the gastrointestinal system and its operations, with particular importance on the control that can be executed via the pelvic floor muscles. | |||

Straining during defecation is dismayed, to reduce pressure on the bladder, pelvic floor, pudendal nerve, and affiliated branches. Patients who have hardship in evacuating without straining are educated to use an evacuation procedure that promotes relaxation at the anal sphincter, in conjunction with utilizing the diaphragm to aid in raising intra-abdominal pressure. If more pressure is required a patient can then be trained to use transversus abdominis to raise pressure and guide the push posteriorly. | |||

Additionally, many patients with anorectal dysfunction may have a flare in their symptoms during stressful episodes, and helping a patient to identify this aspect may aid them to control or reduce relapse of symptoms. Onward referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist may be necessary. | |||

In relation to patient exercise, they are to learn to locate and control the muscles of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall. Patients conferring pain that is related to hypertonicity need to acknowledge a rise in muscle tone and should be taught to relax the muscles to forestall or limit the pain. Part of the exercise program is the regular practice of the correct evacuation procedure. | |||

Manual therapy at pelvic floor level can be used to enhance proprioception, modify muscle tone and change the pain experience. Other techniques in this category include coccygeal mobilization and anal sphincter dilation which are conducted via the anus. A pressure can be applied by the patient on the top of their perineum to allow the patient to recollect that the correct evacuation procedure has been executed. Moreover, intestinal or abdominal massage is another manual technique that can be performed by the physiotherapist during clinic sessions, but can be shown to a patient to perform at home. Finally, active hip and knee flexion to press and relieve the abdominal material can be used as a tool by a patient to promote peristalsis and the clearance of stool and flatulence. | |||

== | == Reference List == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Pelvic Health]] | |||

[[Category:Pelvis - Assessment and Examination]] | |||

[[Category:Pelvis - Conditions]] | |||

Latest revision as of 12:58, 26 June 2023

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Functional anorectal disorders are characterized by constipation and are often associated with ineffective defecation, inappropriate contraction or weakening of pelvic floor muscles, abnormal propulsive forces, or outlet obstruction. Initial treatment is largely nonsurgical and often involves behavioral and diet modification, fiber, and bulking agents. Biofeedback can also be effective for some of these disorders. Surgical management is controversial and with limited studies of varying success.

Functional anorectal include proctalgia fugax, levator ani syndrome, and unspecified functional anorectal pain[1]. These three types of anorectal disorders are chiefly differentiated by the length of time pain is present and by the feature or lack of anorectal tenderness[2]. However, these pain disorders do coincide and are similar to each other[2][3].

Functional Anorectal Disorder Type Definitions[edit | edit source]

Three Types Identified:

- Levator Ani Syndrome: other names include levator spasm, puborectalis syndrome, and pelvic tension myalgia[1]. In this syndrome, pain can be present for 30 minutes to being ceaseless. Its distinguishing attribute is on physical examination a hypertonic levator ani muscle and soreness on palpation of the pelvic floor or vagina[1].

- Unspecified Functional Anorectal Pain: In this syndrome, the pain will also be present for 30 minutes to be continuous in the rectum. However, it does not present with levator ani soreness on palpation[1].

- Proctalgia Fugax: For this disorder, pain is momentary, present for seconds to minutes, and happens sporadically such as once a month or less[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

To date there is no currently published data on the commonness to which chronic anorectal pain is came upon in clinical practice[1].

Pathophysiological Process[edit | edit source]

There is a poor insight into the pathophysiology of functional anorectal pain which sometimes occurs without any pathology[4]. Levator ani syndrome is thought to be caused by hypertonic pelvic floor muscles[1] and may be identified by an increase in muscle tone of the puborectalis sling[5]. It was found the presence of pelvic floor muscle spasms, raised anal resting pressure[6] and dyssynergic defecation[7] are contributors to levator ani syndrome. The latter refers to inefficiency through the defecation process in the anorectum[3] but does not include constipation[1].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients presenting with levator ani syndrome or unspecified functional anorectal pain often describe the feeling of pain as a dull ache or a sense of pressure utmost in the rectum. This is usually aggravated by a long duration of sitting, such as a long-distance car journey, and lessened by standing or lying [3][8][9]. The pain rarely occurs at night but its severity can rise throughout the day. It may be made more severe with sexual intercourse, stress, or defecation[10] [11]. Associations have been made between patients presenting with levator ani syndrome, who are also experiencing psychosocial distress[3] and impacted quality of life[12], this includes anxiety disorders, depression , and stress[10][13]. Other causative factors to functional anorectal pain can include childbirth[14] and surgery, inclusive of herniated lumbar disc, hysterectomy, or low anterior resection[3].

A digital rectal examination may be performed to ascertain the presence of tenderness when traction is applied to the levator ani muscle[15]. Often a lack of symmetry may be noted on the physical exam and pain is mainly left-sided. Presently, there is no logic as to why this side is generally more affected[15]

Summary of clinical features for one of the subtypes of functional anorectal pain[3].

| Variable | Levator ani syndrome |

|---|---|

| Average age | 30-60 years |

| Sex | More in females than male |

| Pain Quality

Pain Duration Typical Pain Location Pain at other sites Precipitating factors |

Vague dull ache or pressure sensation

30 minutes or longer Rectum No Sitting long period, Stress, sexual intercourse, Defecation, Childbirth, Surgical procedure. |

| Urinary symptoms

Sexual dysfunction Psychosocial symptoms |

No

No Possible |

| Internal pelvic tender points

External pelvic tender points |

Yes (Puborectalis) with asymmetry (left side greater than right side). No |

Diagnostic Criteria[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of Levator Ani Syndrome, as per Rome IV criteria [1], must present with all symptoms listed below:

- Chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching.

- Episodes last 30 minutes or longer.

- Soreness during traction on the puborectalis.

- Elimination of other sources of rectal pain, see differential diagnosis below.

- Criteria are to be met for the last 3 months with symptom onset at a minimum of 6 months before diagnosis.

The diagnosis of unspecified functional anorectal pain has the same criteria as that for chronic levator ani syndrome, but there is no soreness during posterior traction on the puborectalis muscle. Again criteria are met for the last 3 months with symptom onset at a minimum of 6 months before diagnosis[1][2].

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

The first line of treatment most commonly provided is reassurance that pain is benign. Conservative lines of treatment are used first in the management of functional anorectal pain, this may include lifestyle adaptations, diet changes, fibers, laxatives, and pelvic floor physiotherapy. However, if conservative management is unsuccessful, these functional disorders can be difficult to treat[16]. In the instance of levator ani syndrome a range of treatments aimed at relaxing the levator ani muscles may be implemented[15];

- Digital massage of the levator ani muscles[17]

- Sitz (or hip) bath[18] Person sits in water up to the hips, used to relieve discomfort/ pain in the lower part of the body, works by keeping the affected area clean and increasing the flow of blood to it.

- Muscle relaxants eg methocarbamol, diazepam[18], and cyclobenzeprine

- Electrogalvanic stimulation (EGS)

- Sacral nerve stimulation[19]

- Biofeedback training A randomized controlled study unveiled that biofeedback is markedly more effective than EGS or digital massage[7].[20] In a more recent review, it was reported biofeedback improves the defecation manner and attested effective for above 90% of patients in the short term[21].

Where conservative management has been unsuccessful botox may be considered as an alternative. In a study conservative management was given for 3 months then treatment with Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A), as well as ongoing physiotherapy by a pelvic floor physiotherapist. BTX-A was found to give a prolonged remedy in 47% of patients with chronic functional anorectal pain. A further 20% had an initial response to treatment but reverted within 3 months[16]. The patient sample size in this study was small, with 113 total. It was noted in patients with solitary hypertonia of the levator ani appeared to present worse than those with only hypertonia of the anal sphincter or a mixture of both, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.06)[16]. In comparison, another earlier study found injection of botulinum toxin into the anal sphincter did not relieve anorectal pain present in levator ani syndrome[23]. This earlier study did not include the combined management of pelvic floor physiotherapy and botox for these patients[16], thus highlighting the value of physiotherapy pelvic health intervention for this patient group.

Physiotherapy Intervention[edit | edit source]

To grasp a full insight into the magnitude and attributes of each patient's symptoms and to devise an individualized treatment plan, the physiotherapy appraisal must take into account the patient's diagnosis, the results of any further investigations, conduct a detailed interview, and comprehensive physical examination. The pelvic floor examination in patients with anorectal disorders is the same as that for patients presenting for urinary incontinence, with particular attention on details admissible to the anorectum.

Anal palpation will assess the measure of the anal sphincter and its resting tone and contractility. The anorectal angle can also be surmised; it is normally between 60h and 130h. Furthermore, feces in the rectum and its texture can be evaluated here, the tone and contractility of the posterior aspects of the pelvic floor muscles (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and ischiococcygeus). The coccyx is an important bone of attachment for the pelvic floor muscles and it's akin fascia, the location and mobility of the coccyx are also assessed, and painful areas can be palpated.

A functional assessment is conducted in supine and sitting positions to allow reproduction of the patient's evacuation endeavors, without actual evacuation. This will give information on whether the patient is producing sufficient push, with enough pelvic floor and anal sphincter easing. Spasms in this area may be provoked during this examination. The sitting posture used by the patient during evacuation is recognized. During this examination the way in which intra-abdominal pressure is raised and its impact on the abdominal wall was noted.

Examination of the abdominal wall is conducted through palpation and functional testing. Palpation of the colon and identification of locations of soreness. Functional activities include coughing or lifting of the upper or lower limbs. Breathing pattern and how the diaphragm moves is assessed. Overall a comprehensive examination of the thoracolumbar spine and pelvis can be performed to give insight of the functional abdominopelvic workings[24].

A variety of physiotherapy treatment choices are accessible, including:

- Patient Education

- Exercise

- Manual techniques

- Biofeedback[24]

- Electrical stimulation

- Balloon techniques

- Functional applications during the evacuation procedure

The treatment of anorectal disorders is many-sided and the selection of treatment has to account for;

- Contractility and patient mastery of the pelvic floor and the anus

- Receptiveness and Conformity at the Rectum

- Intestinal motion

- Evacuation procedure

- Diet

- Yellow flags

To give some further detail into the physiotherapy treatments one can begin to give suitable information at the subjective interview, such as bowel and bladder routines, and diet to establish stool consistency and general health. Thereafter, using a pelvic model, drawings, an information pamphlet, and an evacuation diary to give insight into bowel routines, the patient will prevail of a basic understanding of the gastrointestinal system and its operations, with particular importance on the control that can be executed via the pelvic floor muscles.

Straining during defecation is dismayed, to reduce pressure on the bladder, pelvic floor, pudendal nerve, and affiliated branches. Patients who have hardship in evacuating without straining are educated to use an evacuation procedure that promotes relaxation at the anal sphincter, in conjunction with utilizing the diaphragm to aid in raising intra-abdominal pressure. If more pressure is required a patient can then be trained to use transversus abdominis to raise pressure and guide the push posteriorly.

Additionally, many patients with anorectal dysfunction may have a flare in their symptoms during stressful episodes, and helping a patient to identify this aspect may aid them to control or reduce relapse of symptoms. Onward referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist may be necessary.

In relation to patient exercise, they are to learn to locate and control the muscles of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall. Patients conferring pain that is related to hypertonicity need to acknowledge a rise in muscle tone and should be taught to relax the muscles to forestall or limit the pain. Part of the exercise program is the regular practice of the correct evacuation procedure.

Manual therapy at pelvic floor level can be used to enhance proprioception, modify muscle tone and change the pain experience. Other techniques in this category include coccygeal mobilization and anal sphincter dilation which are conducted via the anus. A pressure can be applied by the patient on the top of their perineum to allow the patient to recollect that the correct evacuation procedure has been executed. Moreover, intestinal or abdominal massage is another manual technique that can be performed by the physiotherapist during clinic sessions, but can be shown to a patient to perform at home. Finally, active hip and knee flexion to press and relieve the abdominal material can be used as a tool by a patient to promote peristalsis and the clearance of stool and flatulence.

Reference List[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Drossman DA, Chang L, Chey WD, Kellow J, Tack J, Whitehead WE and the Rome IV Committees, editors. Rome IV—functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. 4th Edition. Vol 2. Rome Foundation Inc, 2016. p531-535

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Rao SS, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, Felt-Bersma R, Knowles C, Malcolm A, Wald A. Anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016 May 1;150(6):1430-42.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Bharucha AE, Lee TH. Anorectal and pelvic pain. InMayo Clinic Proceedings 2016 Oct 1 (Vol. 91, No. 10, pp. 1471-1486). Elsevier.

- ↑ Iqbal F, Beggs AD, Holt T, Bowley DM. A pain in the bottom. Bmj. 2013 Jul 1;347:f4192.

- ↑ Gilliland R, Heymen JS, Altomare DF, Vickers D, Wexner SD. Biofeedback for intractable rectal pain. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1997 Feb 1;40(2):190-6.

- ↑ Grimaud JC, Bouvier M, Naudy B, Guien C, Salducci J. Manometric and radiologic investigations and biofeedback treatment of chronic idiopathic anal pain. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1991 Aug 1;34(8):690-5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, Romito A, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010 Apr 1;138(4):1321-9.

- ↑ Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. gastroenterology. 2006 Apr 1;130(5):1377-90.

- ↑ Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE and the Rome II Multinational working teams, editors. Rome II: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2nd Edition. Degnon Associates Inc, 2000. p483-542

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wald A. Functional anorectal and pelvic pain. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2001 Mar 1;30(1):243-52.

- ↑ Gilliland R, Heymen JS, Altomare DF, Vickers D, Wexner SD. Biofeedback for intractable rectal pain. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1997 Feb 1;40(2):190-6.

- ↑ Heymen S, Wexner SD, Gulledge AD. MMPI assessment of patients with functional bowel disorders. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 1993 Jun 1;36(6):593-6.

- ↑ Renzi C, Pescatori M. Psychologic aspects in proctalgia. Diseases of the colon & rectum. 2000 Apr 1;43(4):535-9.

- ↑ Salvati EP. The levator syndrome and its variant. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 1987 Mar 1;16(1):71-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Whitehead WE, Wald A, Diamant NE, Enck P, Pemberton JH, Rao SS. Functional disorders of the anus and rectum. Gut. 1999 Sep 1;45(suppl 2):II55-9.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Ooijevaar RE, Felt-Bersma RJ, Han-Geurts IJ, van Reijn D, Vollebregt PF, Molenaar CB. Botox treatment in patients with chronic functional anorectal pain: experiences of a tertiary referral proctology clinic. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2019 Mar 1;23(3):239-44.

- ↑ Salvati EP. The levator syndrome and its variant. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 1987 Mar 1;16(1):71-8.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006 Apr 1;130(5):1510-8.

- ↑ Dudding TC, Thomas GP, Hollingshead JR, George AT, Stern J, Vaizey CJ. Sacral nerve stimulation: an effective treatment for chronic functional anal pain?. Colorectal Disease. 2013 Sep;15(9):1140-4.

- ↑ Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, Romito A, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010 Apr 1;138(4):1321-9.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2847007/(accessed 17.5.2022)

- ↑ Carrington EV, Popa SL, Chiarioni G. Proctalgia Syndromes: Update in Diagnosis and Management. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2020 Jun 9;22(7):35-

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Pelvic Floor Training. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=37a_CXKEj5M [last accessed 25/09/2020]

- ↑ Rao SS, Paulson J, Mata M, Zimmerman B. Clinical trial: effects of botulinum toxin on levator ani syndrome–a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2009 May;29(9):985-91.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Neumann P, Gill V. Pelvic floor and abdominal muscle interaction: EMG activity and intra-abdominal pressure. International Urogynecology Journal. 2002 Apr 1;13(2):125-32.